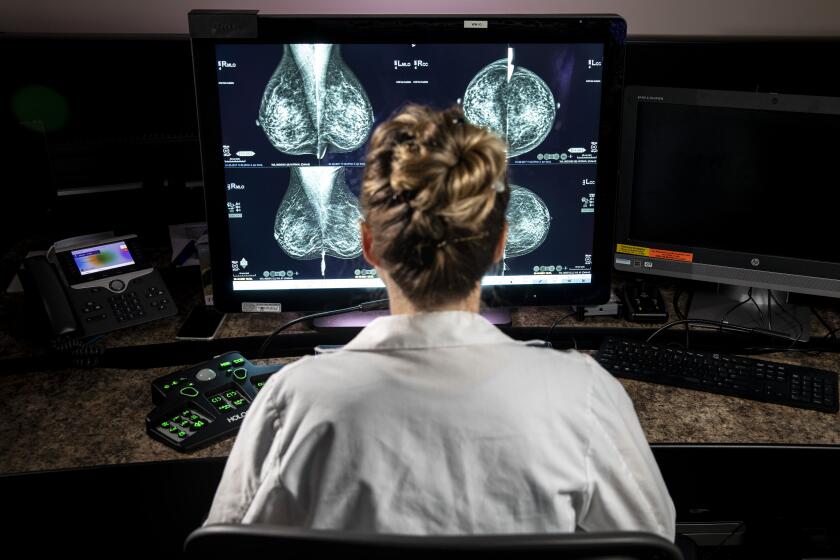

Expert panel that sparked mammogram controversy now says tests should start at 40

A new look at the science of preventing breast cancer deaths promises to reshape when, and how many, mammograms American women will get — again.

An influential panel intends to recommend that U.S. women begin mammograms to screen for breast cancer at 40 and continue getting them once every two years until age 75. Doing so is expected to reduce the number of breast cancer deaths by 19% compared with following the mammography regimen it previously endorsed.

The new slate of draft recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force marks a major shift from the controversial advice it promulgated in 2009 — and largely reiterated in 2016 — that most women could safely wait until 50 to begin having their breasts scanned for signs of potential malignancies. The panel also said women at average risk could be screened every other year instead of annually.

In calling for fewer mammograms over a woman’s lifetime, the task force cited the frequency with which breast cancers were overdiagnosed, leading to invasive yet unnecessary treatment, as well as the harms that come from needless biopsies and other work-ups done in response to false-positive test results. It also recognized that mammograms expose women to radiation, which in some cases could wind up causing cancer in otherwise healthy women.

Those recommendations touched off a firestorm and were denounced by women’s health advocates, who have long argued that early detection gives the best chance of survival.

What prompted the task force to change its mind and advise that screening mammograms begin at 40? The members said they were strongly influenced by the experiences of Black women, who tend to develop aggressive breast cancers earlier than white women do, and to die of them more often. According to one study, Black women are 39% more likely to die of breast cancer than the population of women as a whole.

Why breast cancer is more likely to kill black women

Screening women of color for breast cancer earlier is just the first of many steps that must be taken to close persistent gaps along ethnic lines. For Black, Hispanic, Latina, Asian, Native American and Alaska Native women, timely follow-up and effective treatment for breast cancer will be needed as well, the experts warned.

Also driving the changes in the draft recommendations is a growing recognition of the risks faced by women with dense breasts, which make malignancies both more common and harder to detect on mammographic images.

Almost half of all women have dense breasts, and the task force members said they had little research to guide them on whether to recommend additional screening or other kinds of imaging, such as MRI or ultrasound.

“New and more inclusive science about breast cancer in people younger than 50 has enabled us to expand our prior recommendation and encourage all women to get screened every other year starting at age 40,” said Dr. Carol Mangione, chief of internal medicine at UCLA and the chair of the group that wrote the task force’s proposed recommendation. The new guidelines “will help save lives and prevent more women from dying due to breast cancer,” she added.

For women older than 50 who have been confused by conflicting advice on how frequently to get a mammogram, some new science is here to guide their decisions.

Dr. Patricia Ganz, a breast cancer expert at UCLA who has served on many cancer-screening panels, said that there is little new evidence driving the task force’s shift. But she called the group’s focus on addressing racial inequities in breast cancer “very, very important.” And she said the every-other-year mammography schedule is in line with practices in Canada and Europe.

“I do think this is a very good recommendation: It leaves doctors and their patients a lot of flexibility” to decide how aggressive or relaxed their breast cancer screening should be, Ganz said. “The fact that they recommend starting at 40 means these women will have an opportunity early to engage in a process of calculating their personal risks.”

In doing so, women find they are subject to a range of breast-cancer screening recommendations.

The American Cancer Society suggests women begin annual mammograms at 45, then consider switching to biennial tests at 55. Women who would prefer to begin annual screening at 40 can do so, and they should continue getting mammograms as long as they expect to live at least 10 more years, the ACS adds.

The American College of Radiology and Society of Breast Imaging recommend annual mammography screening for all women ages 40 and older who are at average risk of breast cancer.

Neither group suggests that 75 should be a hard upper limit for screening mammograms. But the American College of Radiology has recommended that all women have a risk assessment for breast cancer by the age of 25, and discuss with their doctor whether earlier screening with mammography and/or MRI is needed.

After a thorough review of the benefits and limitations of mammograms, the nation’s top cancer-fighting organization is advising women that they can wait until they are 45 years old to start using the tests to screen for breast cancer.

Dr. Debra L. Monticciolo, a radiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, was highly critical of the task force’s decision to recommend mammograms every other year considering that Black women and Jewish women die from breast cancer prior to age 50 — or even 40 — more often than white women as a whole. “That’s just going to exacerbate the racial disparities,” she warned.

“Their own evidence shows that the most lives are saved with yearly screening,” said Monticciolo, who led the drafting of the American College of Radiology/Society of Breast Imaging recommendations. “With annual screening of women 40-to-79, you get a 42% mortality reduction. Limit that to every other year, and it drops the mortality reduction to 30%. These are women’s lives that would be saved. I don’t know what their thinking is here.”

The task force noted other consequences of shifting from the least-intensive to the most-intensive screening schedule, however. The number of mammograms a typical woman received tripled, as did the number of false positive readings. The rate of overdiagnosis more than doubled, from 8% of cases to 17%.

Dr. Otis Brawley, a Johns Hopkins oncologist and cancer epidemiologist, said that while it seems counterintuitive that screening less often could save more lives, it’s a possibility that cries out for rigorous testing.

“Even many experts can’t come to grips with how many cancers are caused by mammogram screening and how many deaths are diverted by that screening,” said Brawley. People who carry genes that predispose them to some cancers may be particularly vulnerable to radiation-induced mutations, he said. “But that’s not a trade-off that’s been explored with strong research,” he added.

Radiologists have discovered a new side effect of COVID-19 vaccines: They make it more difficult to interpret mammogram results.

The task force made clear that its new recommendations were not undergirded with rock-solid confidence. That women should begin getting mammograms at 40 had its most solid research backing. But the task force assigned far lower confidence values to its every-other-year schedule of mammography, and to the idea that breast-cancer detection after 75 may not be lifesaving.

“There is very limited research on this age population,” the group’s report acknowledged.

The draft recommendation will be open for public comment until June 5. Comments can be submitted on the task force’s website.