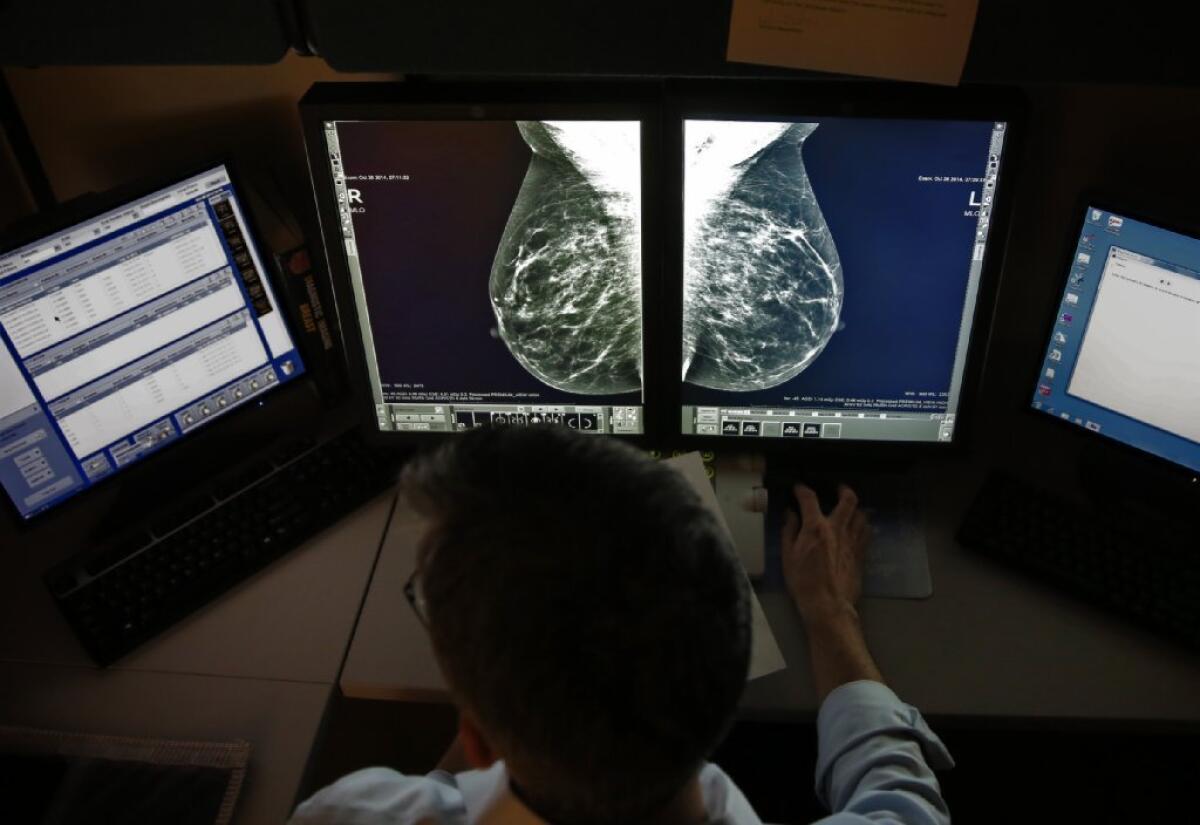

To find breast cancer, more mammograms aren’t better, expert panel says

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force still recommends that most women can wait to start getting mammograms until they are 50, and that they can get the test only once every two years.

Despite years of controversy over the best way to screen women for breast cancer, an expert panel convened by the federal government is standing by its controversial recommendation that most women should get mammograms only once every two years, and that the tests need not begin until the age of 50.

The draft report from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reiterates that mammograms performed on asymptomatic women do indeed save lives. But it also emphasizes the test’s downsides, many of which are underappreciated by doctors and the general public.

Chief among the problems associated with screening mammography is the risk that it will result in unnecessary procedures and treatment by finding abnormal cells that would have been harmless if left alone, according to the panel, which first raised questions about the test in 2009.

“About one out of every five women diagnosed by screening mammography and treated for breast cancer is being treated for cancer that would never have been discovered or caused her health problems in the absence of screening,” according to the report released Monday.

Breast cancer is the second-leading cause of cancer death among women in the U.S., after lung cancer. Among every 10,000 women in the U.S., about 125 are diagnosed with breast cancer each year and 22 die of the disease. That translated to about 233,000 new diagnoses and 40,000 deaths in 2014.

No wonder, then, that women eager to stay healthy have embraced mammograms. Two-thirds of American women ages 40 and above said they’ve had the test within the last two years, including 51% who had it within the last 12 months, according to the American Cancer Society.

Several groups – including the American Cancer Society, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the American College of Radiology – continue to recommend annual mammograms for women at average risk of breast cancer beginning at age 40.

But the task force reiterated its advice that most women get tested only once every two years, and that the test is most effective for women between the ages of 50 and 74.

“Age is the most important risk factor for breast cancer,” the panel wrote.

For instance, if 10,000 women in their 60s were screened for a decade, the result would be 21 fewer deaths due to breast cancer, according to data from clinical trials. Among women in their 50s, the same amount of screening would avert eight breast cancer deaths.

Against those benefits, the experts considered the costs of treating breast tumors that are revealed by mammograms but aren’t dangerous. They also factored in the unnecessary procedures brought on by false-positive test results as well as the small but real number of breast cancers that are caused by the radiation in mammograms.

Overall, the panel determined “the net benefit of screening mammography in women ages 50 to 74 is moderate.”

But for most women in their 40s, the net benefit of screening is too small to warrant a blanket recommendation in its favor, the panel determined.

“Women ages 40 to 49 must weigh a very important but infrequent benefit (small reduction in breast cancer deaths) against a group of meaningful and much more common harms,” according to the report. These harms include “overdiagnosis and overtreatment; unnecessary and sometimes invasive followup testing and psychological harms associated with false-positive tests; and false reassurance from false-negative tests.”

However, if women in this age group have a first-degree relative – a mother or sister – who has been diagnosed with breast cancer, their own risk of the disease is comparable to that of a typical woman in her 50s. As a result, biannual screening for these women makes sense, the panel wrote.

Researchers have not conducted clinical trials to test the value of screening mammograms among women over the age of 70. Mathematical models indicate the tests can be useful for women between the ages of 70 and 74. Beyond that, the data needed to endorse the test for older women is “insufficient,” the panel wrote.

All of these recommendations are in line with those made in 2009.

The task force also considered whether 3-D digital mammograms could do a better job of finding breast cancers than the standard exams. Studies suggest that the more sophisticated scans result in fewer false-positive test results, and they do help doctors find more abnormal cells.

However, there is no evidence that finding these cells extends lives or reduces the morbidity associated with breast cancer treatment, the panel wrote. It’s not even clear that the type of cells discovered are dangerous and require treatment.

One thing that is clear is that the 3-D scans expose women to twice as much radiation as the regular exams, according to the report. Altogether, the experts decided there wasn’t enough evidence to offer advice about the scans one way or the other.

The task force also decided there was too little evidence to make a recommendation for or against specialized screening regimens for women with dense breasts. These women are up to 30% more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer, although they are no more likely than other women to die of the disease. A 3-D X-ray imaging technique called tomosynthesis can help doctors find more tumors that are invasive and potentially most dangerous. But it is not yet clear that early detection of these tumors improves cancer outcomes for women, the panel said.

In 2009, the panel advised doctors not to teach their patients to perform breast self-exams. That advice was not updated in the new report.

As radiologists like to say, “The more you look, the more you find.” That has certainly been the case with mammograms.

Before they became a widespread tool to screen for breast cancer, doctors were finding about six cases of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) for every 100,000 women per year. After mammograms were established as the standard of care, the discovery rate ballooned to 37 per 100,000 women per year. Today, about one-quarter of all breast cancer diagnoses involve DCIS, according to the task force.

The problem is, some cases of DCIS will become invasive breast cancers and others will not. But doctors can’t tell which is which. So nearly all women get treated as if their tumors are dangerous. That involves surgery, and often radiation and treatment with tamoxifen.

At least 98% of women who get treated for DCIS are still alive after 10 years. But it’s not clear that all that therapy deserves the credit.

“Whether this is due to the effectiveness of the interventions or the fact that the majority of DCIS cases being treated are essentially benign is unclear,” the task force wrote.

This is not a problem that can be solved with better mammography technology alone, the report said. Scientists also need to conduct studies to figure out how to tell which tumors are truly dangerous and which tumors can be safely left alone.

In the meantime, the task force members lamented, there’s no good way to paint a clearer picture of “what the best screening strategy is for women, or how clinicians can best tailor that strategy to the individual woman.”

The task force’s draft recommendations are available for public comment through May 18.

For more medical news, follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.