For some COVID patients, ‘Paxlovid rebound’ has nothing to do with Paxlovid

This is a story about a COVID-19 medication, a nasty trick the coronavirus sometimes plays on its victims, and how the two became a pandemic couple called “Paxlovid rebound.”

It’s also a story about how looks can be deceiving.

Americans have been quick to embrace the idea that the antiviral drug is to blame for COVID-19 relapses in people just days after they’ve seemingly recovered. President Biden was said to have experienced Paxlovid rebound this summer, after White House doctors declared him coronavirus-free. The same thing happened to Dr. Anthony Fauci and Stephen Colbert, among others.

It’s tempting to presume a cause-and-effect relationship between two things that occur in quick succession. And even when events are completely random, we tend to see the patterns we expect to find.

But researchers are not so sure Paxlovid rebound is real. Relapses have occurred in COVID-19 patients who didn’t take the drug — they just didn’t get as much attention when there wasn’t a new medicine to blame.

Doctors fear some patients who could benefit from Paxlovid are skipping it in an effort to avoid a boomerang bout of COVID-19. That’s troubling because the medication has been found to powerfully reduce the risk of hospitalization or death in the unvaccinated, older people and those with compromised immunity. Preliminary research hints it may even reduce the risk of long COVID.

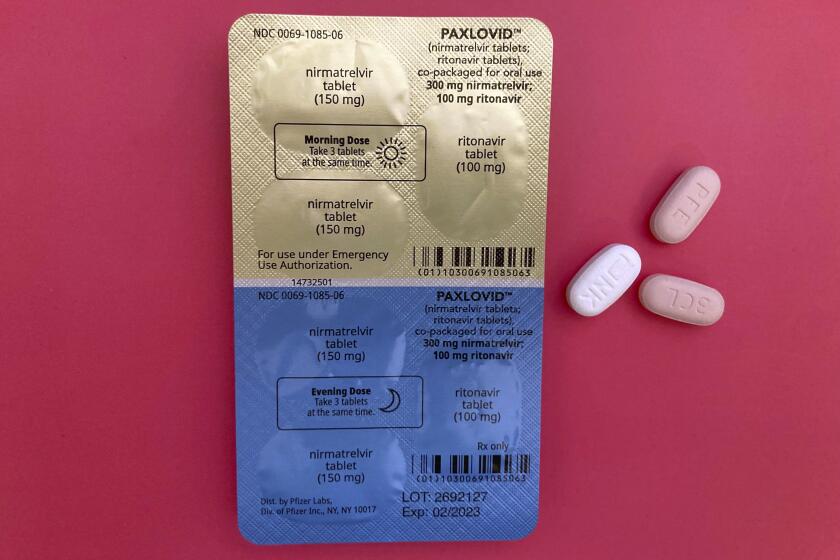

There are two antiviral pills available for eligible patients who have recently tested positive for the coronavirus. And they’re free.

Dr. Michael Charness, who led a team that exhaustively studied 13 patients whose COVID-19 rebounded, admitted that the phenomenon has scientists “scratching our heads.” He said he’s perplexed that many rebounders’ viral loads — and thus, their ability to infect others — can be just as high or higher than it was during their initial illness.

“But rebound is not a reason to not take Paxlovid,” he insisted. When used by people with a good chance of becoming severely ill or dying, Paxlovid reduces the odds of either by almost 90%.

Moreover, passing on Paxlovid out of concern that it will prompt a one-two punch of COVID-19 is unlikely to help, Charness said.

“It’s clear some people will rebound anyway,” he said.

That wasn’t so clear in late May, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a health advisory titled “COVID Rebound After Paxlovid Treatment.” It informed doctors and public health officials of recent cases in which people who had taken the recommended five-day course of Paxlovid and then tested negative for a coronavirus infection had “recurrent illness” two to eight days later.

The alert cautioned that the rebound phenomenon may be a feature of COVID-19 “independent of treatment with Paxlovid,” and the CDC stressed that it continued to recommend use of the antiviral medication. Yet in the public square, a causal link was quickly forged. Conversations buzzed with accounts of neighbors and co-workers who took Paxlovid and experienced the boomerang effect.

Health experts are urging people to be cautious if they develop symptoms again after taking anti-COVID pills.

By late June, researchers at Harvard Medical School published a study in the Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases that described seven COVID-19 patients who relapsed following a course of Paxlovid. In September, Charness and his colleagues at the VA Boston Healthcare System and elsewhere weighed in with their report in the New England Journal of Medicine on the progression of illness, recovery and recurrence in 13 patients who took Paxlovid to treat their COVID-19.

Authorized by the Food and Drug Administration nearly a year ago, Paxlovid has carried the hopes of doctors and public health officials who count on it as a rescue drug for the unvaccinated and a backup for vaccinated people in fragile health. It’s more effective, and has fewer safety concerns, than molnupiravir, another antiviral made by Merck. And unlike antibody treatments and the medication remdesivir, it’s a pill meant to be taken at home.

The Biden administration’s “test to treat” initiative made Paxlovid easy to find at pharmacies, at no cost to patients. But it hasn’t exactly taken off. In a poll conducted this summer by a consortium of universities, only 11% of those who’d had a coronavirus infection since Jan. 1 said they received a prescription for the drug.

“If people qualify for Paxlovid, they should take it. It’s a lifesaver. Period,” said Dr. David Smith, an infectious diseases specialist at UC San Diego. “I hate that rebound has been tagged as a Paxlovid effect.”

Indeed, the more scientists learn, the more they’ve come to believe that relapses have been happening throughout the pandemic.

A preliminary study led by Dr. Jonathan Z. Li, an infectious disease expert at Harvard, was the first to suggest that rebound might just be another of the SARS-CoV-2 virus’ dirty little tricks.

Li is part of a group tracking the clinical progression of thousands of COVID-19 patients. He and his colleagues combed their records to identify 568 mildly ill COVID-19 patients who had not been treated with Paxlovid. Ten percent of them reported a return of symptoms after they thought they’d recovered, and 12% experienced a resurgence of viral loads after the coronavirus had become undetectable, the team reported in a preliminary study posted online in August.

Health officials recommend that anyone infected with the coronavirus isolate for at least 5 days — but for many, that timeline may be overly optimistic.

In September, a dispatch in the New England Journal of Medicine bolstered the case that rebound happens even in the absence of Paxlovid. Researchers from Pfizer, which makes the drug, reported that in a clinical trial with 1,970 infected participants, viral rebound occurred in 2.3% of subjects who were treated with Paxlovid as well as 1.7% of subjects who got a placebo medication instead.

Within weeks, a report in JAMA Network Open offered additional evidence that rebound has been a feature of COVID-19 all along. In a group of 158 COVID patients tracked closely for 28 days, 30% reported that they suffered a return of symptoms after feeling well for two days — and that was in the summer and fall of 2020, before Paxlovid was available.

There’s even new research suggesting that Paxlovid provides protection against long COVID, a phenomenon that’s distinct from rebound but also features an extended run of COVID-19 symptoms.

The analysis of more than 56,000 COVID-19 patients treated in the Veterans Affairs health system found that those who took Paxlovid were 26% less likely to have long COVID symptoms after 90 days than those who didn’t. The study was posted on medRxiv this month and has not been reviewed by independent scientists.

Americans who still aren’t fully vaccinated against COVID-19 probably have some immunity from a past infection. They may not be so dangerous anymore.

Even though it’s clear COVID-19 can rebound without the help of Paxlovid, scientists still have good reason to figure out whether there’s any real link.

Antiviral medications act by gumming up a pathogen’s replication machinery. But viruses rarely take that challenge lying down. They mutate constantly, and are quick to capitalize on any changes that help them overcome a drug’s defenses.

Thousands of laboratory encounters between Paxlovid and the coronavirus have confirmed that the risk of inducing a Paxlovid-resistant virus is real. But in cases where patients relapsed after taking Paxlovid, scientists have found no signs that the virus has changed, Charness said.

“It wasn’t a new infection or mutation that made virus immune to Paxlovid,” he said. “It was just ‘Night of the Living Dead’” — the same virus coming back.

That’s actually good news, because it means Paxlovid has not yet driven the coronavirus to incorporate a mutation that allows it to short-circuit a highly effective medication.

But it still could. A medicine that weakens a virus but doesn’t finish it off puts that virus under tremendous pressure to evolve. It may behoove doctors to prescribe a longer course of the drug, or to create a more formidable cocktail by combining it with molnupiravir.

“I have learned never to bet against this virus,” Li said.