For almost two years, COVID-19 vaccine holdouts have been the objects of earnest pleading and financial inducements, of social-media shaming and truth campaigns. They’ve missed weddings, birthday celebrations and recitals, and even forfeited high-stakes athletic competitions. Until last month, they were barred from entering the United States and more than 100 other countries.

Now the unvaccinated are suddenly back in the mix. They’re dining in restaurants, rocking out at music festivals and filling the stands at sporting venues. They mingle freely in places where they used to be shunned for fear they’d seed superspreader events.

It’s as if they’re no longer hazardous to the rest of us. Or are they?

“Clearly, the unvaccinated are a threat to themselves,” said Dr. Jeffrey Shaman, an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University. As recently as August, their risk of dying of COVID-19 was six times higher than for people who were fully vaccinated and eight times higher than for people who were vaccinated and boosted, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But, Shaman acknowledged, “the danger to the rest of us is a more debatable issue.”

The Path From Pandemic

This is the third in an occasional series of stories about the transition out of the COVID-19 pandemic and how life in the U.S. will be changed in its wake.

When public officials imposed vaccine mandates, the unvaccinated certainly appeared to pose demonstrable dangers to their communities.

State and local leaders sought not only to suppress spread of the virus, but also to prevent their healthcare systems from being overwhelmed, degrading care for all. The unvaccinated made those goals harder to achieve since they were more likely to become infected and, when they did, to require hospitalization.

U.S. officials had long hoped to vaccinate the American public into a state of “herd immunity,” in which so few people would be vulnerable to the virus that the outbreak would simply sputter out. That objective assumed a uniformly high uptake of vaccine across the nation. It also assumed a vaccine that protected against reinfection, and did so durably.

Experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have set aside herd immunity as a national target for ending the pandemic.

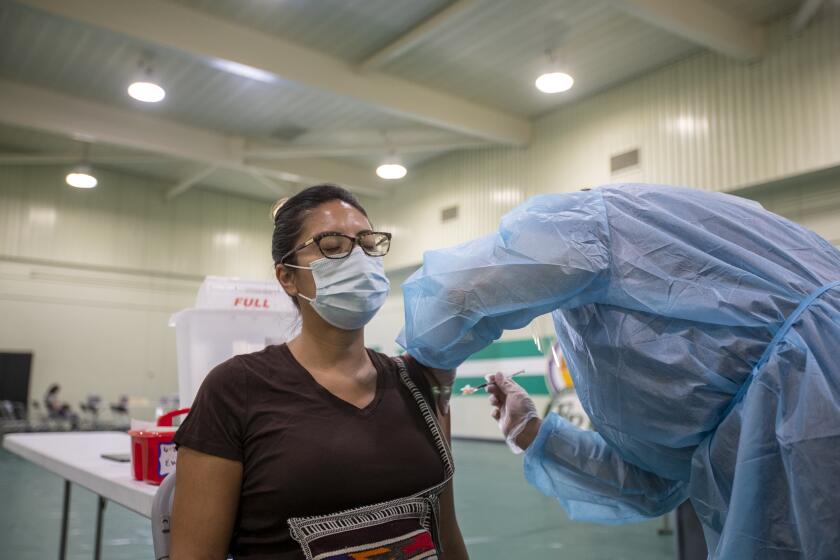

But none of that came to pass. About 30% of Americans have yet to complete their initial series of COVID-19 shots, including the 20% who haven’t rolled up their sleeves even once. Meanwhile, the virus continues to evolve in ways that erode vaccines’ protection, making “breakthrough infections” increasingly common.

The longer the pandemic drags on, the more complicated things get.

For one thing, whether those who remain unvaccinated are still driving coronavirus spread hinges partly on the status of the U.S. population’s immunity. Almost three years into the pandemic, that is a hard map to draw — both because the public’s immunity comes from different sources and because it waxes and wanes.

More than 200 million adults and nearly 25 million children ages 5 and up have completed a primary series of COVID-19 vaccine. However, against the Omicron variant, just being “fully vaccinated” confers little more than a whiff of protection against infection and illness.

For the 49% of “fully vaccinated” Americans who’ve had at least one booster dose, infection remains a possibility, but the prospects of becoming seriously ill or dying of COVID-19 are sharply reduced.

Deciding how many Americans we are willing to let die of COVID-19 each year is necessary to put the pandemic behind us.

And then there’s the “natural immunity” gained from a coronavirus infection. By February 2022, after the first wave of Omicron infections swept across the U.S., 58% of Americans were believed to have been infected at some point in the pandemic, leaving them with some modest level of protection. The ranks of the previously infected have surely increased since then thanks to the second Omicron surge during the late spring and summer.

An unknown number of Americans have “hybrid immunity” from both an infection and vaccine. Researchers believe that catching the coronavirus after vaccination (though not so much the other way around) may provide enhanced protection against severe illness and death. But whether that is the case — and how much — can vary based on how long ago an infection took place and the particular variant that caused it.

In other words, Americans range in vulnerability from the unvaccinated and never infected to the vaccinated, previously infected and fully boosted, with infinite gradations of protection in between.

In conditions like these, the role the unvaccinated could play in seeding outbreaks will vary.

“It’s kind of a patchwork,” said Harvard University epidemiologist Stephen Kissler. “It’s changing over time, and it’s changing over space. So it’s hard to say where any given community is at any given time.”

The steady waning of immunity raises a discouraging prospect: that over time, people who are still called “fully vaccinated” will become indistinguishable from the unvaccinated unless they’ve received a booster. Until more Americans embrace booster shots, the “undervaccinated” will steadily swell the ranks of the vulnerable.

In a large study, the risk of a breakthrough infection was 10 times lower for people who got a COVID-19 booster shot than for people who hadn’t.

Wherever they are, they’ll help keep the pandemic going.

The country’s mainstay vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna do not construct a force field around recipients that shields them from ever becoming infected with the coronavirus. Nor do they prevent a person with a breakthrough infection from spreading the virus to others.

However, the vaccines appear to reduce the amount of virus a sick person sheds by coughing, sneezing or simply talking. That means unvaccinated people are not only more likely to be infected, but also somewhat more likely to spread it to others.

It would be hard to assert that if everyone were vaccinated, the coronavirus would just go to ground. This pathogen has proved adept at finding ways around our vaccine protection and is likely to remain a presence among us for generations to come, like influenza and HIV.

But the unvaccinated and undervaccinated are almost certainly playing an outsized role in the coronavirus’ continued success, experts say. Exactly how much is hard to pinpoint. Scientists can quantify transmission differences between the vaccinated and the unvaccinated in the lab. Applying those differences to the real world is much trickier, especially in a population as immunologically diverse as Americans now are.

A young Briton agreed to be infected with the coronavirus for a scientific study of the most consequential virus on the planet.

Finally, there’s concern that unvaccinated and undervaccinated Americans could accelerate the emergence of new coronavirus variants, some of which are bound to be even more transmissible or more adept at evading existing COVID-19 vaccines and therapies. Either — or both — would cause new waves of transmission and illness.

While it’s a theoretical possibility, the unvaccinated are not prolific incubators of genetic variants. People with immune system deficiencies are much more likely to develop the long-running bouts of COVID-19 that can spawn new variants with concerning mutations, and most of them are vaccinated.

COVID-19 surges promote the emergence of variants. By virtue of the sheer number of people infected, a surge increases the number of times the virus replicates and offers it more chances to mutate. If it drives hospitalizations, it will ensnare patients being treated for immune-compromising conditions such as HIV, cancer and organ transplants.

If the U.S. public health emergency ends, Americans would be vulnerable to a new coronavirus variant that sparks another COVID-19 surge.

And as the unvaccinated are joined by ever-larger numbers of people who are undervaccinated, surges become a more plausible prospect.

People routinely confuse their communities’ state of immunity with their own vulnerability, said Dr. Peter Hotez, co-director of the Center for Vaccine Development at Texas Children’s Hospital and dean of Baylor College of Medicine’s National School of Tropical Medicine. When fewer of their neighbors are getting sick and dying, and high vaccination rates have suppressed COVID-19, even the unvaccinated feel invulnerable.

“That could be a lethal mistake,” he warned.