Q&A: Why COVID-19 booster shots turned out to be more complicated than vaccines

Just a few months ago, the protection offered by COVID-19 vaccines brought Americans joy and relief, allowing the fully immunized to ditch their masks and return to a semblance of pre-pandemic life. Now that protection seems more like an illusion.

What happened?

Has our vaccine-induced immune response really fizzled? Is the Delta variant to blame for waning vaccine effectiveness? Is the resurgent dread of COVID-19 warranted? Will booster shots restore our protection — and the hope that came with it?

Both the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Protection grappled with these questions before giving the go-ahead to boosters in certain populations. If that guidance seemed disjointed or confused, it was largely because the science is still emerging.

Factor in the crosswinds of politics, fear, rampant misinformation and a vaccination campaign that has lost its momentum, and things become even more fraught.

For instance, in declining to recommend that a third dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine be made available to all who got their second dose at least six months earlier, members of a CDC advisory panel made clear they did not want to undermine public confidence in COVID-19 vaccines when so many haven’t even gotten their first dose.

How did we get here?

Let’s start by acknowledging that vaccines were never perfect

Even in clinical trials, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was reported to be 95% effective at preventing cases of COVID-19. That means the risk of becoming sick after getting the shots was small but not zero — and it doesn’t say anything about the vaccine’s ability to thwart a coronavirus infection in the first place.

Moreover, that lofty figure was unlikely to hold under real-world conditions. In the United States, close to 3% of adults are immune-compromised and therefore unlikely to mount a strong protective response to a vaccine. Plus, new viral variants are continually being incubated domestically or imported from abroad.

Random mutations to the coronavirus’ genome might alter it in ways that could make it more transmissible, or enhance its ability to make people seriously ill. Another worry is that mutations may change the virus in ways that prevent vaccine-induced antibodies from recognizing it.

The rise of the Delta variant shows that scientists are right to be worried. In chart after chart, FDA and the CDC experts cited research suggesting that the now-dominant strain has helped erode vaccines’ effectiveness in myriad ways.

Lab tests and real-world experience offer reassuring evidence that COVID-19 vaccines offer a high level of protection against the Delta variant.

Vaccines affect the immune system in complex, and mysterious, ways

The first months following immunization are the heyday for antibodies: They’re plentiful, recently trained to recognize their target virus, and varied enough to recognize several of its features. A virus looking to invade is unlikely to sneak past.

But as that initial spate of antibodies decays, the immune system can rely on its memory banks — the legions of white blood cells in which resides the battle plan for fighting a new infection. The appearance of a virus should prompt these specialized cells to swing into action. Helper T cells stimulate B cells to produce a fresh crop of antibodies. They also prompt other T cells to hunt down cells that have been infected and kill them.

But this process isn’t instantaneous, and if the coronavirus can establish itself in the nose and mouth quickly enough, the immune system may not respond fast enough to bar the gates. Infection happens.

For most people — but clearly not all — the cavalry will arrive in time to blunt an all-out invasion and head off severe disease. That may explain why researchers have found that the longer the time since vaccination, the greater the odds that inoculated people test positive for a coronavirus infection, even though the rate at which they’re being hospitalized for COVID-19 has risen much less steeply.

This pattern has been observed in Israel, Qatar and the United States. In one study that focused on New York, the three available vaccines’ combined ability to prevent infection fell from 92% in early May to about 77% in late August, and the decline was seen in all age groups. Yet during the same period, when age was taken into account, the vaccines’ effectiveness in preventing hospitalization held steady. (By mid-June, however, hospitalization rates among vaccinated adults over 65 did begin to climb.)

We look at the science behind the need for COVID-19 booster shots.

When it comes to immunity, age matters

Immunity generally weakens as we get older, and so does our response to vaccines. Both of those facts have been key in the current pandemic.

Before vaccines became available, people 65 and older were by far most likely to die of COVID-19. So they were among the first Americans to get vaccine — and particularly the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, which became available first.

That makes senior citizens the age group furthest out from vaccination. And with clear evidence that they’re once again vulnerable to severe COVID-19, advisors to the FDA and CDC agreed that those 65 and up who received their second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine at least six months earlier should have a booster shot of that vaccine made available to them.

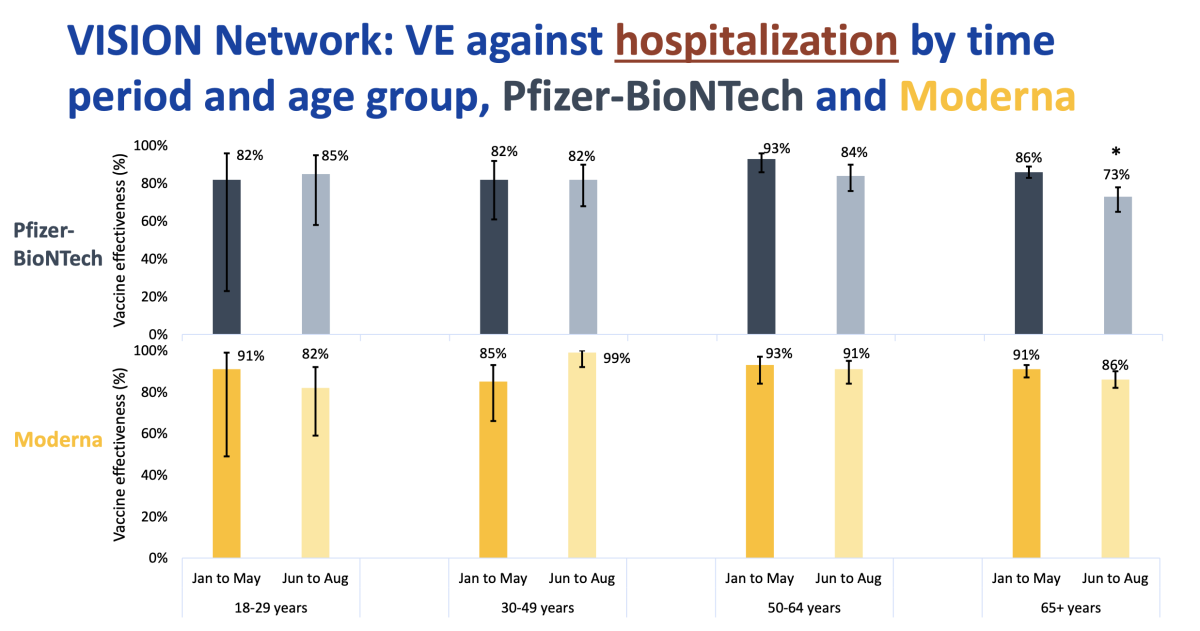

A study by the CDC suggests this group is among those most in need of booster shots. For those 65 and over in the U.S. who got the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, the protection against being hospitalized for COVID-19 fell from 86% between January and May to 73% between June and August.

Older Americans who got the Moderna vaccine fared better: Their protection declined from 91% to 86%, a difference too small to be statistically significant.

)

For the most part, the Moderna vaccine held up better than the Pfizer-BioNTech one in all age groups, though all of the changes were small enough that they could have been due to chance.

The explanation for this trend is not at all clear. It could reflect the importance of age, the length of time since vaccination, or the particular vaccine they got.

Dose probably matters too

Other variables likely play a role in a vaccine’s longevity, though scientists still have much to learn. For instance, does the number of times a vaccinated person is exposed to the coronavirus affect his or her risk of infection? Does the amount of virus matter? Do these (or other) factors influence the risk of becoming severely ill?

The answers are of vital interest to healthcare workers and others with essential jobs who are in frequent contact with people who may carry the virus. If vaccine protection can be overwhelmed by frequent or high doses of the virus, these workers could need periodic refreshers as long as the pandemic continues.

The uncertainty was reflected in last week’s regulatory actions regarding booster shots.

On Wednesday, the FDA amended its emergency authorization for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine to allow the use of a booster in adults “whose frequent institutional or occupational exposure to SARS-CoV-2 puts them at high risk of serious complications” of COVID-19.

The following day, the CDC’s Advisory Panel on Immunization Practices voted against an identical proposal after several panel members argued there was not enough evidence these workers would benefit. But within hours, CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky set aside that advice and signed off on providing these workers access to boosters.

What’s true for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine may not be true for others

Three vaccines protect Americans, and they’re each unique.

The ones made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna use mRNA to instruct cells to make a piece of the coronavirus that’s big enough to train the immune system to recognize it, but far too small to do any damage.

Beyond that, the two vaccines are formulated differently. The Pfizer product contains 30 micrograms of vaccine, an amount that’s the same for all three doses. Moderna’s first and second shots have 100 micrograms of vaccine, but its booster dose contains 50 micrograms.

Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine does a significantly better job of preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations compared with Pfizer’s shot.

The timing of shots also differs. Pfizer’s first two doses are given three weeks apart, and Moderna’s are spaced four weeks apart.

Vaccine experts have begun to suggest that giving the immune system more time to respond to an initial dose before giving the second one might make for stronger, and possibly more durable, immunity. The additional week between Moderna doses might be an important reason for that vaccine’s comparatively better staying power.

Either way, a period of six months between the second and third shots may be even better for inducing lasting immunity.

The single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine uses a more traditional vaccine design — a harmless cold virus with a payload that introduces the immune system to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

In its opening days, the vaccine was found to reduce the risk of symptomatic infection by 66%, and a later study reported that it reduced the risk of severe disease in people over 50 by 68%.

There’s some evidence that the Delta variant has reduced its effectiveness, although a study sponsored by J&J showed that a single jab reduced the risk of COVID-19 by 79% without any decline as the Delta variant rose to prominence. A large study published by the CDC found that protection against hospitalization fell to 60% after Delta became dominant in the U.S.

Last week, J&J released preliminary findings of a large study that tested the value of adding a second jab. None of those who received a booster shot 56 days after their initial dose developed a severe or critical case of COVID-19. Among study participants in the United States, the booster reduced the risk of moderate disease by 94%.