Why are COVID-19 booster shots needed anyway?

From the pandemic’s earliest days, scientists have counted on COVID-19 vaccines to lead us out of the global health emergency. But they’ve also been aware that the immunity provided by vaccines might not last very long.

Mounting evidence in support of that suspicion prompted the Biden administration’s endorsement of booster shots Wednesday as a way to shore up Americans’ biological defenses against the coronavirus, especially the highly transmissible Delta variant.

If the Food and Drug Administration determines that boosters are safe and effective, third doses of the vaccines made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna will be available the week of Sept. 20.

The shots should be administered to fully vaccinated adults eight months after they received their second dose, the White House said Wednesday. They’ll be made available to Americans at 40,000 local pharmacies and another 40,000 approved vaccination sites, said Jeff Zients, the Biden administration’s coordinator of pandemic response.

Public health officials released a welter of research showing that the two vaccines most widely used in the United States have become less effective over time at blocking infections among fully vaccinated adults of all ages.

Officials made clear they suspect there are two factors at work: a natural waning of immunity in some of those vaccinated and the rising dominance of the highly transmissible Delta variant in the United States starting in early May.

The new studies don’t measure how much each factor has eroded the effectiveness of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. But however it breaks down, officials said they were determined to avert a rise in COVID-related hospitalizations and deaths among the vaccinated.

Health officials recommended people receive a booster shot eight months after their second dose of COVID-19 vaccine, ‘to maximize protection.’

“We are concerned that the current strong protection against severe infection, hospitalization and death could decrease in the months ahead, especially among those who are at higher risk or who were vaccinated earlier,” said Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Our plan is to protect the American people and to stay ahead of this virus,” she added.

The most convincing evidence for vaccines’ diminishing effectiveness had come from Israel. Despite vaccinating roughly 68% of its population ages 12 and older, the nation has seen cases doubling every seven to 10 days since June. More than half of the new infections occurred in fully vaccinated people.

The new U.S. research makes clear Israel’s renewed vulnerability is no fluke.

One study published Wednesday by the CDC that tracked close to 14 million residents of New York state reported that the vaccine’s effectiveness at preventing coronavirus infection in fully vaccinated adults declined from 91.7% on May 3 to 79.8% on July 25.

A preliminary study that Mayo Clinic researchers posted online last week found that between March and July, the average protection afforded by the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines fell from 78% to 44% in people in five states where the clinic operates.

And a report from the CDC’s COVID-19 Response Team concluded that among nursing home residents — a medically fragile population that has been most vulnerable to severe illness and death — the vaccines’ power to prevent infection dropped from 74.7% in the 10 weeks leading up to May 9 to 53.1% in the subsequent six-week period.

Unleashing a fast-spreading coronavirus variant on a half-vaccinated population can lead to a vaccine-resistant strain.

There were some reassuring findings too. Over the five months following full vaccination, both healthy adults and those with underlying medical conditions saw no significant decline in the shots’ power to prevent COVID-19 hospitalizations, according to another new study published by the CDC.

Scientists’ early surmise that vaccine-induced immunity against COVID-19 would wane quickly was based on previous experience with other coronaviruses — especially four species of seasonal coronavirus that have circulated for as long as modern medicine has been paying attention.

Those four members of the coronavirus family differ in many ways from the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19, not least because they lead to nothing worse than a common cold. But scientists assumed their family resemblances would be revealing.

A 1990 research effort that involved infecting British volunteers with those coronaviruses found that after a year, most still had elevated antibody levels. Those extra antibodies didn’t shield them from reinfection when they were deliberately exposed again, but none developed cold symptoms and most cleared the virus quickly.

Another study published in 2020 tested a small group of healthy people at least twice a year for more than 12 years. It found that immunity in people infected by any of those four coronaviruses rarely lasted much longer than 12 months. In some instances, reinfection occurred in as little as six months.

A national vaccine court has paid out billions to those who’ve been injured by vaccines. But the program doesn’t help the rare victims of COVID-19 vaccines.

Early on, the remarkable effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna made some scientists optimistic that the pattern might change.

In a preliminary report posted online last month, researchers at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology found that people who received the Moderna vaccine developed the levels of immunity that augured well for lasting protection.

Even better were the specific types of immunity the researchers found, including the long-lasting T cells that continue to generate protective antibodies.

“I thought from the start there’d be a 50-50 chance we’d need vaccines in a year,” said Shane Crotty, a vaccine researcher at the La Jolla Institute who has co-written two studies on SARS-CoV-2 immunity. “But we found a lot of evidence of durable immunity that would probably last for years in most vaccinated individuals.”

In Israel, however, so-called breakthrough infections have become evident — especially in older people and those with health conditions that make them more susceptible to the virus. Virtually all of the infections there have involved the Delta variant, which replicates much more quickly than its predecessors and may be able to get past the immune system’s defenses while it’s still ramping up.

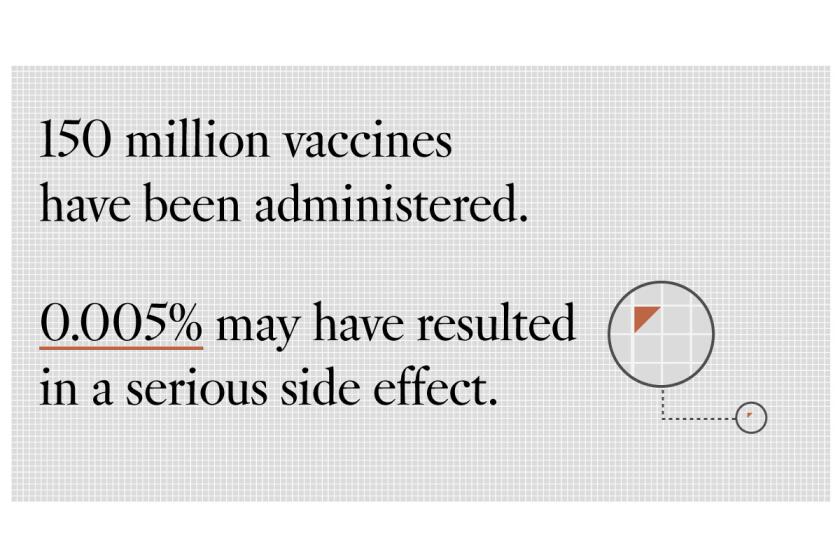

Questions about COVID-19 vaccines’ safety have led to hesitancy for some Americans. Experts say there is almost zero cause for concern.

Israel’s experience furnished some of the first evidence that the anticipated drop-off in immunity had begun. And since the country is already administering booster shots to people over age 60, it is likely to offer clues about how well they will extend protection.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said Wednesday that a third jab will shore up recipients’ immunity.

“You get a dramatic increase in antibody titers when you do a third immunization dose,” he said.

Facui cited a study published last week in Science showing that antibodies capable of blocking infection typically begin to decline roughly four months after a second dose of Moderna’s vaccine. And he pointed to evidence in the New England Journal of Medicine that it will take higher antibody levels to keep the Delta variant at bay.

Some scientists are skeptical that antibodies against COVID-19 will have the last word on immunity. Against a wily and fast-changing virus, they say that “cell-based immunity” from T cells and B cells is a better measure of protection, and that efforts to bolster that second line of defense will yield better and more durable results.

Crotty said he’s still not convinced that booster shots need to be in everyone’s future.

The U.S. plan to offer boosters to people eight months after their second dose “is a better-safe-than-sorry kind of decision,” Crotty said.

“Are boosters required, or critically needed? I don’t think the data support that,” he said. “Will boosters help? Will protective immunity be better? Yeah! They top off antibody levels, and the trials look great.”