The dilemma in pausing J&J vaccine over risk of blood clots: Will it save lives or cost them?

“Do no harm.”

The phrase, from the Hippocratic oath, is the guiding principle of medical care. It was uttered multiple times during a highly charged meeting this week of vaccine experts who convened to advise the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the safest course of action after six people who got Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine developed a rare blood-clotting disorder.

The experts on the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or ACIP, decided to hold off on making decisions until more data — and potentially more patients with blood clots — emerge.

But they made clear that even a brief pause in the use of one of three authorized vaccines will leave some Americans vulnerable a little longer to a serious case of COVID-19. Some of them will surely join the more than 565,000 Americans who have died of the disease. But some who would have gotten the vaccine and gone on to develop a blood clot might also have died.

In a situation like this, the advisors asked themselves, what does it mean to “do no harm”?

“I would characterize it as wrenching,” Vanderbilt University vaccine expert Dr. William Schaffner said of the meeting, which he attended as a nonvoting representative of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. “All you had to do was listen to the stress in the voices of my colleagues as they discussed this.”

In the best of times, doing no harm is a delicate balancing act. After all, healing the sick routinely involves risky procedures and medicines that can kill as well as cure.

That trade-off is even more fraught where vaccines are concerned. Perturbing the immune system of a healthy person to prevent an infectious disease just might save her life — if she’s exposed to the disease-causing germ. But vaccines might elicit dangerous reactions in some people who would never have caught the bug in the first place.

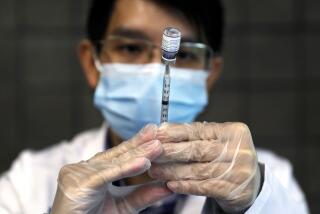

Two COVID-19 vaccines have now been linked to a risk of developing blood clots. Scientists don’t know whether the vaccines are to blame.

Now put this conundrum in the context of a raging pandemic that’s infecting roughly 70,000 Americans a day and has killed 3 million people worldwide.

“It’s a hard balance to strike,” said Dr. Camille Nelson Kotton, a committee member who specializes in treating immunocompromised patients at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Kotton said the Johnson & Johnson “one-and-done” jab is especially well-suited to the needs of her patients, including organ transplant recipients leaving the hospital on immune-suppressing drugs and homebound people with compromised immunity.

Many of Kotton’s patients had been scheduled to get the Johnson & Johnson shot over the next few days. Now, she said, they will continue to be at high risk of becoming gravely ill if they encounter the coronavirus.

As a single-shot vaccine that requires no special handling, J&J’s vaccine has been seen as a solution for those who might not show up for a second shot due to transportation problems, job or child-care demands or an overload of life challenges. It was expected to be a boon not only for young people and essential workers but also for those made vulnerable by addiction, poverty and lack of shelter.

“This is very special vaccine,” Schaffner said. Already at high risk, “some will become infected” before the pause is lifted, he said.

The ACIP makes recommendations to the CDC on when, how and to whom vaccines should be given. It’s best known for drafting the nation’s pediatric vaccination schedule.

A half-dozen cases of life-threatening blood clots handed the 15-member group an agonizing dilemma.

The cases emerged from reports made either to Johnson & Johnson or to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, a database run by the CDC and the Food and Drug Administration. All six cases were women between the ages of 18 and 48 who had received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in the previous two weeks — a tiny fraction of the roughly 6.8 million Americans who’d gotten it by early this week.

Safety officials on Tuesday urged a temporary halt in administration of the vaccine in the United States.

Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the CDC director, said the pause was necessary to alert healthcare providers about the best way to treat this rare type of blood clot and investigate whether there were additional cases that have not been reported.

“The safety systems we have in place are working,” Walensky said.

But it also set up the ACIP’s predicament. Should the panel recommend a continued pause until the vaccine’s safety could be better understood? Should it advise that vaccinations resume with new safety measures in place? Should it suggest that the shots be limited to groups, such as men and women over 50, that haven’t shown a propensity to develop the unusual clotting problems?

A full resumption of vaccinations with warnings to doctors — a solution the FDA made clear it would support — drew no backers on the panel. And members appeared wary of resuming vaccinations for all but younger women; after all, it was pointed out, the age of the six women with blood clots could simply reflect the fact that the people who received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine were younger, overall, than those who got shots made by Moderna or Pfizer-BioNTech.

In addition, many men with unusual blood clots have shown up in Europe and the United Kingdom after a shot of AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine, which is similar to the one from Johnson & Johnson.

Ultimately, after more than four hours of briefings and debate, the ACIP said it would need more time and information before choosing any option.

The result: 9.2 million doses of Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine now sit in boxes at drugstores, doctors’ offices and administration sites across the country.

Reports of blood clots among those who got Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine may make some recipients anxious. Here’s how to handle those feelings.

State and territorial health officials have been told they can count on weekly deliveries of 14 million doses of Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, which are not under suspicion because of their different design.

The country has “more than enough” Pfizer and Moderna vaccine to meet President Biden’s goals, said Jeffrey Zients, chair of the White House COVID-19 task force. But he acknowledged that “in the very short term, we do expect some impact on daily averages” of the number of people vaccinated in the U.S.

Just over half of the 7.8 million vaccinated with the Johnson & Johnson product to date got their jab in the two-week period before federal officials announced a pause in administration of the vaccine.

That leaves a key piece of the puzzle missing: If the feared blood abnormalities are to appear in any of those who were given the shot, they could take up to two weeks to show up and a day or two more for regulators to assess their link — if any — to the vaccine.

Plus, with vastly more public attention focused on the possible link, more cases will probably show up. That, in turn, would drive up estimates of the risk.

In the face of such uncertainties, the panel kicked the can just slightly down the road. The members will reconvene April 23 to issue a recommendation.

Some of the proceedings’ participants could barely hide their exasperation over the delay.

“We’re in a position where not making a decision is tantamount to making a decision,” fumed Dr. Nirav D. Shah, who heads Maine’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention and serves as an ACIP liaison for the Assn. of State and Territorial Health Officials. Reminding the panel that 5,000 deaths had accumulated in the past seven days, Shah added, “Our most vulnerable will remain vulnerable.”

Indeed, hospital admissions and deaths have ticked higher in the last week, reflecting concerns that Americans have grown tired of wearing masks and complying with other mitigation efforts. There were an average of 712 deaths each day in the last week, up from 643 the week before that.

We explain what vaccine passports are, how they work, where they’ve been implemented, and why some people object to them.

U.S. health experts are already trying to counteract vaccine hesitancy among some Americans. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s leading expert on infectious diseases, said he hopes the Johnson & Johnson pause will be seen as a sign that officials are taking safety issues seriously and haven’t “cut corners” in the vaccine-development process.

But fostering confidence in the government’s vaccine response is a tightrope act. For every American encouraged by the federal government’s transparency and prompt response, there are others who consider it an overreaction that undermines confidence. And then there are the reluctant who had been coming around to the idea of getting a shot, only to have their fragile resolve shaken.

“It’s a big challenge, especially the ‘do no harm’ aspect of this decision,” Kotton said. “There are multiple components here: individual health, community health and societal health.”

After all, she said, doing no harm to individuals is different from doing no harm to communities or to the nation as a whole.

Times staff writer Chris Megerian in Washington contributed to this report.