Q&A: What are vaccine passports, and why do some people hate them so much?

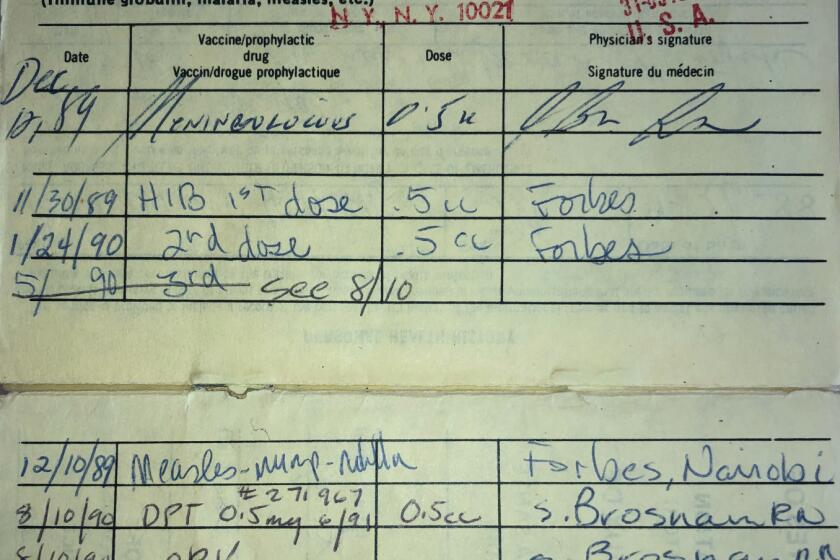

As government-issued documents go, the “COVID-19 Vaccination Record Card” is about as bland as a 1099 from the IRS. The 3-by-4-inch piece of white card stock bears the logo of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and contain a few key pieces of information, including the recipient’s name, date of birth, and the type and lot number of the shot administered.

Yet the country is convulsed by a debate over the information it bears and whether it will become the basis for government-issued vaccine passports.

Could such passports dictate where we work and play, whether we can go to school, or how we travel? Who would have the legal authority to issue them or require their use? Is the data that would back them up accurate and secure? Would a system involving vaccine passports be inherently unfair?

The answers to these questions are complicated by the United States’ federalist system, which empowers states and counties to take the lead on policies related to public health. Beyond that, Americans prize their personal freedoms and are wary of governmental actions that curtail them.

We are all eager for the pandemic to end so that businesses can reopen and we can travel and mingle freely, and mass vaccination is the only way to get there without hundreds of thousands more deaths.

A safe return to life as we knew it may depend on vaccination records, and some form of proof would be, at least, a convenience. Whether it becomes a requirement for rejoining the world is more controversial.

Here’s a closer look at vaccine passports and why their use has become so controversial.

Do vaccine passports even exist?

To some extent. For now, all vaccinated people in the U.S. get those CDC cards, which are then stuffed into wallets, laid on bedside tables and sometimes shared on social media. The information contained on these cards is collected by state immunization registries.

Every state and territory except New Hampshire has long had a system for tracking childhood vaccinations, and all — including New Hampshire — now share their COVID-19 vaccination data with the CDC. That’s what allows the federal government to track how many Americans have been vaccinated, along with some demographic details.

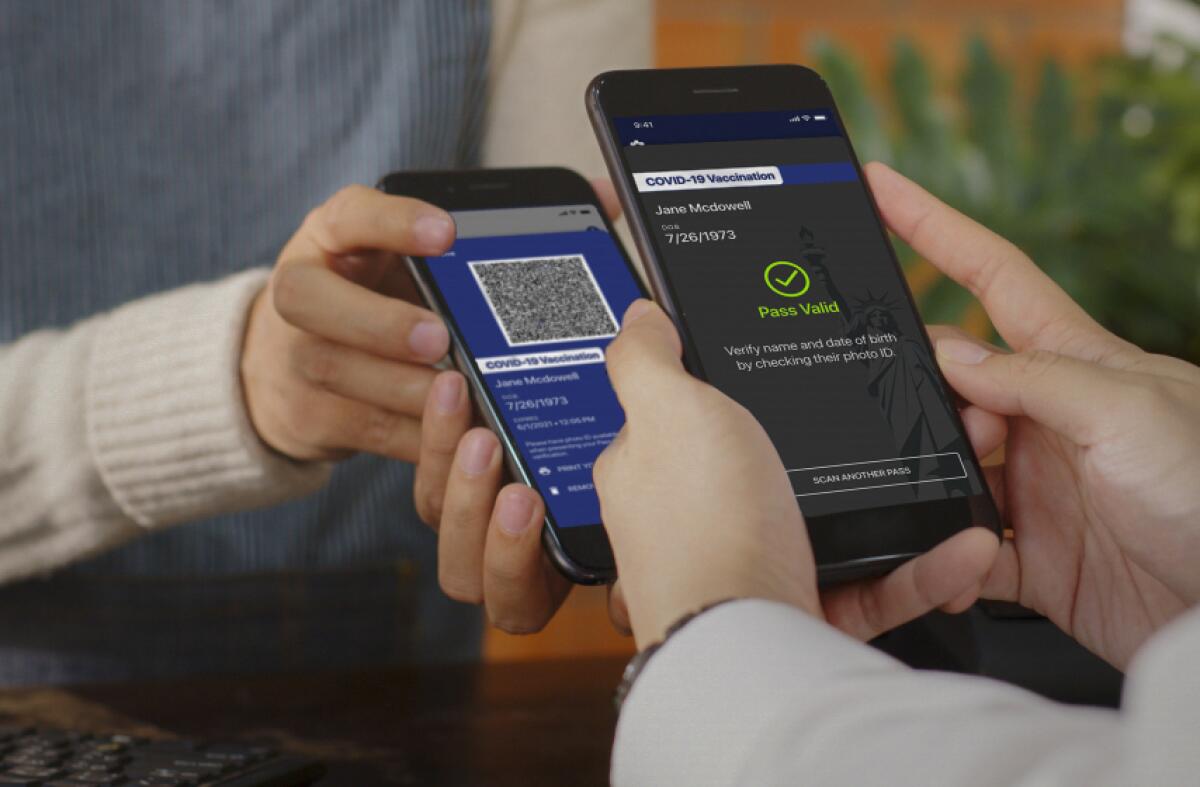

Right now, only one state — New York — has said it would issue an “Excelsior Pass” to residents vaccinated against COVID-19. Printed out or downloaded to a digital device, the pass “supports a safe reopening” of New York and would be used “as needed to gain entry to major stadiums and arenas, wedding receptions, or catered and other events above the social gathering limit,” according to Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

The pass, a version of IBM’s Digital Health Pass, would make COVID-19 vaccination or test result data presentable without the need to share other personal or medical information.

The European Union plans to issue “Digital Green Certificates” by mid-June. These would allow EU residents to download proof of COVID-19 vaccination, a past infection or test results.

Israel has already issued a “green passport” that allows vaccinees to go to restaurants and attend public gatherings that have been barred or limited by lockdowns.

Can the government require vaccination passports?

States have broad latitude to set rules for where and when proof of vaccination is required and under what circumstances waivers may be issued. The federal government: not so much. Last week, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said the Biden administration would not issue vaccine passports.

“The government is not now, nor will we be, supporting a system that requires Americans to carry a credential,” Psaki told reporters. “There will be no federal vaccinations database and no federal mandate requiring everyone to obtain a single vaccination credential.”

That’s just as well, since a federal mandate would be “questionable legally, and there’s not much precedent,” said Lawrence Gostin, a Georgetown University expert on public health law. “Compulsory powers is the third rail of politics in America. So the federal government wants to stay well clear” of anything that suggests it is mandating vaccination, he said.

But some federal involvement may be hard to wiggle out of, said Dr. Marcus Plescia, medical director of the Assn. of State and Territorial Health Officials.

“I would be surprised if we did not have federal mandates or expectations around international travel,” he said.

Immigration and border control are the responsibility of the federal government, and people coming to the United States from other countries might reasonably be required to show evidence of vaccination, Plescia said. Similarly, Americans traveling to countries where the coronavirus continues to circulate might be required to show proof that they are not carrying the virus back with them.

The federal government also has a crucial role in supporting states’ systems of vaccine registries, he added. Without the federal government’s technical support, public health guidance and funding, states would be hard pressed to develop a system that would work for businesses and individuals who cross state lines.

Can states require proof of vaccination?

Yes.

States do have the power to mandate vaccinations in the interest of the public’s health, to require proof of vaccination, and to specify the circumstances under which exceptions will be granted, Gostin said. The Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld their authority to require vaccinations against childhood diseases for attendance at schools and employment in sectors where the risk of infection are high, including at hospitals, he said.

Local governments’ powers to mandate vaccination stem mainly from a 1905 Court decision handed down during the smallpox epidemic 115 years ago. In 1902, the city of Cambridge, Mass., required its residents to be vaccinated against the highly infectious disease or pay a penalty of $5. A citizen sued Massachusetts for enforcing the law, arguing that it infringed upon his liberties.

In response, the Supreme Court ruled that “the rights of the individual may at times, under the pressure of great dangers, be subjected to such restraint to be enforced by reasonable regulations as the safety of the general public may demand.”

“A community has the right to protect itself against an epidemic of disease which threatens the safety of its members,” Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote in the 7-2 opinion.

The drive for vaccine certificates isn’t a matter of government overreach by out-of-control Democrats; it’s a product of the free-enterprise system.

Whether and how states will use those powers will probably vary. Just as governors have restricted the operations of commercial establishments and placed limits on the size of gatherings, they could make proof of vaccination a condition of resuming activities.

Some states have ruled that out. Republican Govs. Greg Abbott of Texas and Ron DeSantis of Florida have said they would forbid the use of vaccine passports by any entity in their states, including private businesses.

Gostin said blanket prohibitions like those will likely face legal challenges. Not only do they fly in the face of the state’s role in taking positive measures to protect the public’s health, he said. They also prevent private entities from taking steps to protect their employees and customers from infection. And the right of commercial entities and private associations — from stores and restaurants to colleges and hospitals — to protect their employees and clientele from harm is very broad, experts say.

Can private employers mandate a vaccine?

They can and they have, said Joanne Rosen, a legal expert and senior lecturer in health policy and management at Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Law and the Public’s Health.

While an employer must have a “reasonable basis” for the requirement, such requirements are common, Rosen said.

Your questions about vaccination-related civil liberties, privacy and discrimination are answered.

Hospitals and long-term care facilities now routinely require their staffs to be vaccinated each year against flu. Even if neither the state nor county has demanded it, these employer mandates can be defended in court because employees are at greater risk of contracting vaccine-preventable illnesses and because they work with people who are especially vulnerable if they do become infected.

Is it even fair to require proof of COVID-19 vaccination?

Both legally and ethically, such a mandate would be difficult to defend now, when the vaccine is not equally available to everyone.

Mandating vaccination as a condition for any activity would disadvantage people who aren’t yet eligible, including those who are too young to get the vaccines that have received emergency use authorization from the Food & Drug Administration.

In addition, under current conditions of shortage, such mandates arguably would have a discriminatory effect on low-income communities and ethnic groups that have faced hurdles to getting vaccinated.

To withstand legal challenges, any vaccination mandate would have to show that access to vaccines, and to records that show proof of vaccination, was fair, free and easy, Gostin said. The federal government has checked off one of those boxes by assuming the cost of vaccination and, more recently, by funding state distribution plans.

As vaccine hesitancy among communities of color begin to soften and distribution efforts that target disadvantaged communities gain traction, these fairness concerns “will go away,” Plescia said.

The idea of vaccine passports isn’t new, as international travelers and families with school-age children will tell you.

However, requiring vaccine passports would probably be near-impossible so long as COVID-19 vaccines are dispensed under an FDA emergency use authorization. Until the shots gain the agency’s formal approval, they are still considered “investigational.” So an individual’s reluctance to take it on safety grounds probably would not be grounds for denying her anything.

The measure that gave the FDA the power to grant emergency use authorization requires that individuals receiving such a product be informed “of the option to accept or refuse administration.” It came into being when the U.S. military wanted to compel American service members to be immunized against anthrax. Despite a variety of legal maneuvers, the investigational status of the government’s anthrax vaccine assured that no service members could be required to take it against their will.