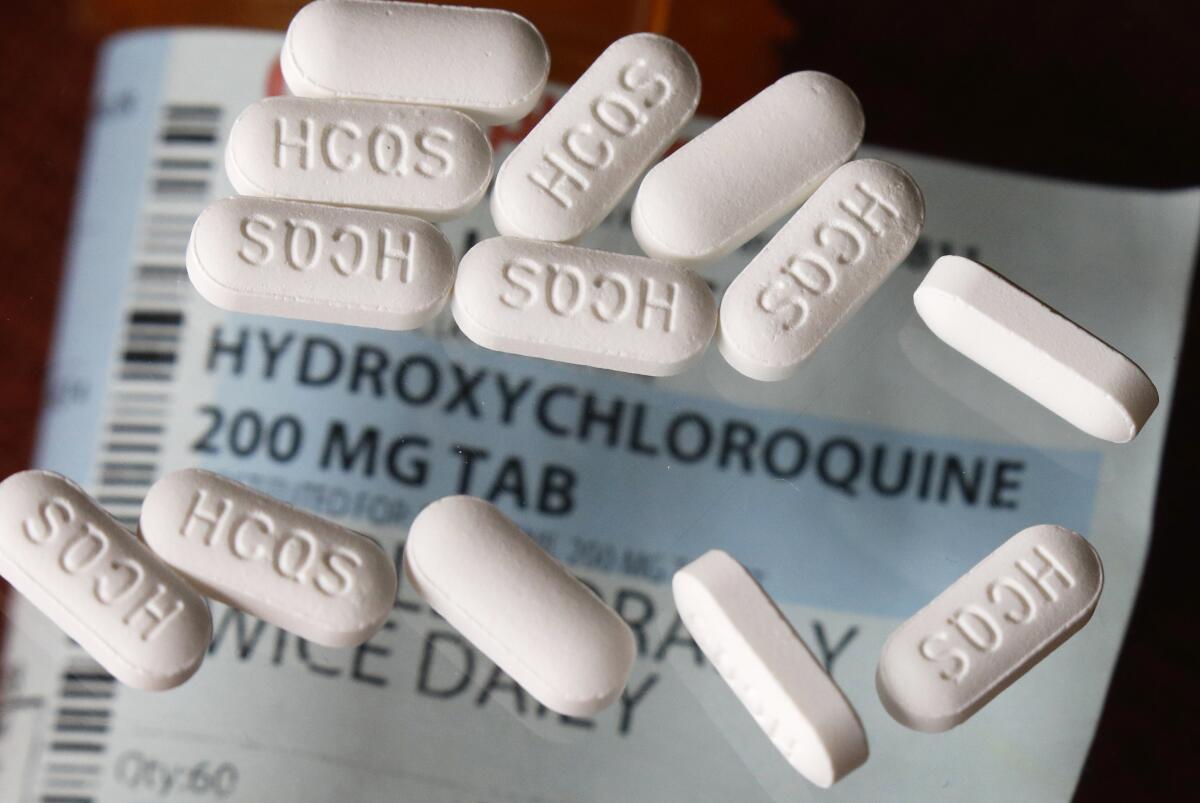

Malaria drugs fail to help coronavirus patients in controlled studies

The malaria drugs touted by President Trump as potentially “the biggest game changers in the history of medicine” have received a decidedly more sober assessment of their coronavirus-fighting potential from researchers in China, France and Brazil.

Both chloroquine and its close relative hydroxychloroquine offered signs that they may ease some of the hallmark symptoms of coronavirus infection in patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19. But the drugs largely failed to deliver improvements on other key measures when evaluated in rigorous research studies.

In research done in France, hydroxychloroquine reduced neither deaths nor admissions to intensive care units among patients who received it. In a study conducted in China and another in Brazil, the two drugs failed to help patients clear the coronavirus faster.

And in Brazil, two deaths and a rash of heart troubles among patients who got a high dose of chloroquine prompted a hasty alteration of the trial there after just 13 days. Concluding that “enough red flags” had been raised, the researchers halted testing of the drug in its extra-strength form.

“My own impression so far is that these medications are a colossal ‘Maybe,’” said Dr. Michael H. Pillinger, a professor of medicine at New York University and chief of rheumatology at the Veterans Affairs’ New York Harbor Healthcare System.

“Is there enough possible benefit that we could use these on a wing and prayer until something better comes along? I’m underwhelmed” by the evidence for that, Pillinger said.

In the Brazil study, two of the 37 patients who were getting high doses of chloroquine developed ventricular tachycardia, a dangerous heart arrhythmia that led to their deaths. Five other patients in this arm of the trial developed QT interval prolongation, a condition that makes the heart’s electrical system slower to recharge between beats. It can cause the heart to beat erratically, also raising the risk of sudden death.

The death toll among patients who were randomly assigned to receive high-dose chloroquine did not rise above that in a comparison group of patients who did not get the drug. But researchers had set out to establish that high-dose chloroquine would save lives. When it failed to do so, they concluded the risks of cardiac side effects could not be justified.

“Preliminary findings suggest that the higher chloroquine dosage should not be recommended for COVID-19 treatment because of its potential safety hazards,” the study authors wrote in a report posted Thursday to MedRxiv, a clearinghouse for preliminary research results.

After the two deaths, the remaining 39 patients were switched to a lower dose of chloroquine, which was already being tested in 40 other patients. All would be tracked for an additional 13 days, with results still to come.

The prospect that malaria drugs will become go-to medications to treat COVID-19 before they’ve been rigorously tested is prompting safety warnings.

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has allied himself closely with President Trump and has echoed his extravagant claims about chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. He has ordered the Brazilian army to ramp up its orders of chloroquine and told the public that the malaria drugs “could go down in history as having saved thousands of lives in Brazil.”

The authors of the Brazil study, which was conducted in the Amazonian city of Manaus, suggested that Bolsonaro’s support complicated their efforts to test the drugs as rigorously as they would have liked.

Normally, they would have conducted a head-to-head comparison by randomly assigning some people to get the drugs while others received a dummy pill, or placebo. But since the drugs have been “recommended at the national level,” the researchers were unable to assign anyone to a group that would not get chloroquine. Instead, they used “historical data from the literature to infer comparisons.”

The French study of hydroxychloroquine, posted Tuesday to MedRxiv, followed a more conventional design. Researchers there enrolled 181 COVID-19 patients who were admitted to four French hospitals over the last two weeks of March, then compared the outcomes of 84 people who quickly received hydroxychloroquine to 91 patients who never received the drug. (Patients in both groups got a range of other treatments, including antiviral medications, corticosteroids and breathing support.)

The researchers found that treatment with hydroxychloroquine did not reduce the likelihood that a COVID-19 patient would die or be admitted to the intensive care unit within a week of hospital admission. Nor did it drive down a patient’s likelihood of developing serious breathing problems.

Hydroxychloroquine did, however, raise some risks. Eight of the 84 patients who got hydroxychloroquine experienced changes in heart rhythm that required discontinuation of the drug, and another patient developed a related heart-rhythm disorder.

“The negative clinical results of this study argue against the widespread use of hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia,” the French researchers concluded.

Medicines designed to treat COVID-19 won’t be available for months, so doctors are looking to drugs already approved for treating other diseases.

Chinese researchers were just a bit more encouraging.

Their study, also posted to MedRxiv on Tuesday, found that COVID-19 patients who got hydroxychloroquine were no better at clearing the coronavirus from their systems than patients who didn’t get the drug. And at the 28-day mark, patients in both groups had the same number of symptoms.

But two weeks after admission to the hospital, patients who got hydroxychloroquine reported they felt better than their counterparts who did not. And they appeared to have lower levels of inflammation — a symptom of COVID-19 that can escalate and lead to death if unchecked. (In fact, in doses much lower than those tested in the COVID-19 trials, hydroxychloroquine is used to treat autoimmune diseases such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis because of its anti-inflammatory effects.)

Also, while 30% of the patients who got hydroxychloroquine reported a side effect, just 9% of patients in the comparison group did so. None of these side effects appeared to be heart-related.

The Chinese researchers referred to “shreds of evidence” that support the hope that hydroxychloroquine could help patients fend off bouts of inflammation that can damage the lungs and other organs.

But researchers in the United States cautioned that the small number of patients in the studies, their hurried execution and the difficulty of assessing any drug during a medical crisis made all of the findings far from definitive. And it doesn’t help that the drugs have become political footballs, they added.

“We kind of have the red pill people and the blue pill people,” said Dr. Michael J. Ackerman, a Mayo Clinic cardiologist who was among the first to warn that the malaria drugs can dangerously disturb heart rhythms. “I don’t think either side now has the ammunition to say these drugs do or don’t work,” he added.

Yale University cardiologist Harlan Krumholz agreed. He noted that the studies, none of which has been vetted in a traditional peer-review process, “can’t exclude large effects in either direction. They leave us a little bit where we started.”

But there is a troubling signal in these and previous studies, and they create a challenge for those who would advocate use of the malaria drugs, he said.

When a drug that could be widely used poses potentially deadly dangers to the heart, “we will need a strong amount of evidence that they provide benefit,” Krumholz said. “At the moment, there is no evidence” for that, he added.