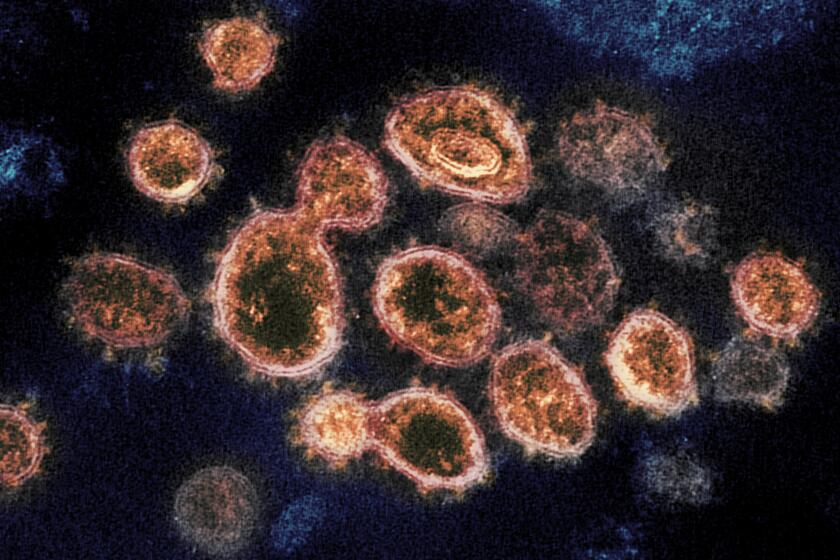

Pfizer says its COVID pill cuts hospitalizations and deaths by nearly 90%

Pfizer says that in studies, its COVID-19 pill cut rates of hospitalization and death by nearly 90% in high-risk adults.

WASHINGTON — Pfizer said Friday that its experimental antiviral pill for COVID-19 cut rates of hospitalization and death by nearly 90% in high-risk adults, as the drugmaker joins the race to bring the first easy-to-use medication against the disease to market.

Currently, most COVID-19 treatments used in the U.S. require an IV or injection. Competitor Merck’s COVID-19 pill is already under review at the Food and Drug Administration after showing strong initial results, and Britain on Thursday became the first country to authorize its use.

Pfizer said it would ask the FDA and international regulators to authorize its pill as soon as possible, after independent experts recommended halting the company’s study based on the strength of its results. Once Pfizer applies, the FDA could make a decision within weeks or months. If it’s authorized, the company would sell the drug under the brand name Paxlovid.

Researchers worldwide have been racing to find a pill against COVID-19 that can be taken at home to ease symptoms, speed recovery and reduce the crushing burden on hospitals and doctors.

Having pills to treat early COVID-19 “would be a very important advance,” said Dr. John Mellors, chief of infectious diseases at the University of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in the Pfizer study.

“If someone developed symptoms and tested positive, we could call in a prescription to the local pharmacy as we do for many, many infectious diseases,” he said.

Merck will let other drug firms worldwide make its COVID-19 pill, a treatment that could be a major new weapon in the fight against the coronavirus.

Pfizer released preliminary results Friday of its study of 775 adults. Patients taking the company’s drug along with another antiviral had an 89% reduction in their combined rate of hospitalization or death after a month, compared to patients taking a dummy pill. Fewer than 1% of patients taking the drug needed to be hospitalized, and no one died. In the comparison group, 7% were hospitalized, and there were seven deaths.

“We were hoping that we had something extraordinary, but it’s rare that you see great drugs come through with almost 90% efficacy and 100% protection for death,” Dr. Mikael Dolsten, Pfizer’s chief scientific officer, said in an interview.

Study participants were unvaccinated, had mild to moderate COVID-19 and were considered high risk for hospitalization because of health problems such as obesity, diabetes or heart disease. Treatment began within three to five days of initial symptoms, and lasted for five days. Patients who received the drug earlier showed slightly better results, underscoring the need for speedy testing and treatment.

Pfizer reported few details on side effects but said rates of problems were similar between the groups at about 20%.

A new study found a cheap antidepressant reduced the need for hospitalization among high-risk adults with COVID-19.

An independent group of medical experts monitoring the trial recommended stopping it early — standard procedure when interim results show such a clear benefit. The data have not yet been published for outside review, the normal process for vetting new medical research.

Top U.S. health officials continue to stress that vaccination remains the best way to protect against infection. But with tens of millions of adults still unvaccinated — and many more globally — effective, easy-to-use treatments will be critical to curbing future waves of infections.

The FDA has set a public meeting later this month to review Merck’s pill, known as molnupiravir. The company reported in September that its drug cut rates of hospitalization and death by 50%. Experts warned against comparing preliminary results because of differences in the studies, including where they were conducted and what types of variants were circulating.

“It’s too early to say who won the hundred-meter dash,” Mellors said. “There’s a big difference between 50% and 90%, but we need to make sure the populations were comparable.”

Numbers from the California Department of Public Health show that initial demand for booster shots has been much lower than originally expected.

.

Although Merck’s pill is further along in the U.S. regulatory process, Pfizer’s drug could benefit from a safety profile that is more familiar to regulators, with fewer red flags. While pregnant women were excluded from the Merck trial because of a potential risk of birth defects, Pfizer’s drug did not have any similar restrictions.

The Merck drug works by interfering with the coronavirus’ genetic code, a novel approach to disrupting the virus. Pfizer’s drug is part of a decades-old family of antiviral drugs known as protease inhibitors, which revolutionized the treatment of HIV and hepatitis C. The drugs block a key enzyme that viruses need to multiply in the human body.

The drug, which has not yet been named, was first identified during the SARS outbreak originating in Asia during 2003. Last year, company researchers decided to revive the medication and study it for COVID-19, given the similarities between the two coronaviruses.

The U.S. has approved one other antiviral drug for COVID-19, remdesivir, and authorized three antibody therapies that help the immune system fight the virus. But they have to be given by IV or injection at hospitals or clinics, and limited supplies were strained by the last surge of the Delta variant.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.