About one-third of dementia cases could be prevented by actions that begin in childhood, experts say

More than 1 in 3 cases of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of

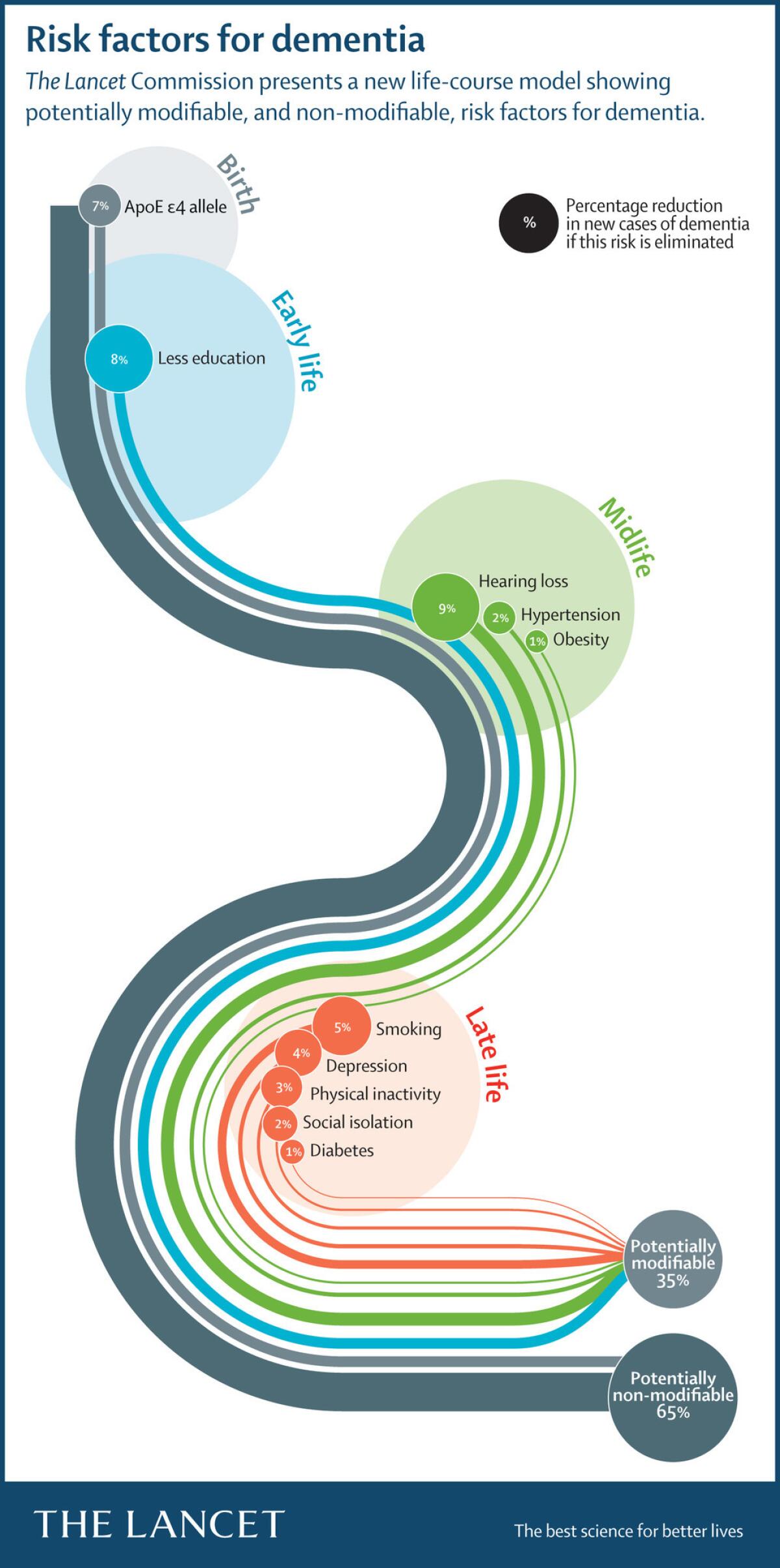

These challenges first present themselves in childhood, and they continue to make their presence felt all the way through one’s senior years. But if all of these problems could be fixed, at least 35% of seniors who lose their independence and their pasts would instead retain their dignity and their memories until they died of something else, the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention and Care has concluded.

This would require doctors, communities and governments around the world to implement things like universal preschool and senior visiting clubs; rebuild cities to encourage exercise and healthy diets; and expand preventive healthcare (along with insurance policies to pay for them). And that’s just a start.

It’s a tall order, the commission acknowledged in a report published Thursday in the medical journal Lancet. But it would be worth it.

For countries bracing for a tsunami of citizens needing wraparound care in their final years, a 35% reduction in dementia would reduce a crushing burden on productivity, government spending and economic growth.

In 2015, roughly 47 million people were thought to be living with dementia, and $818 billion was spent worldwide on their care. The number of dementia sufferers is expected to triple by 2050, and that growth is likely to be greatest in low- and middle-income countries such as China, India, Brazil and Indonesia.

Dr. Lon Schneider, an Alzheimer’s Disease specialist at USC’s Keck School of Medicine and one of the report’s senior authors, said the Commission has produced a roadmap to reducing the global burden of dementia. The avenues it suggests are rarely solutions to dementia alone, he added: whether the recommendation is to keep kids in school, manage high blood pressure in midlife or reduce seniors’ social isolation, such initiatives pay other dividends as well.

New research on the links between air pollution and Alzheimer’s risk might even nudge the power of preventable factors in dementia still higher, Schneider said. Indeed, he said, many recent findings have come to light too late to be reflected in the new report.

The good news is that many of the world’s most affluent countries — the United States, United Kingdom, Sweden, Canada, the Netherlands — are already on the right path.

In recent years, all those countries have seen unexpected declines either in the number of dementia patients or the rates at which seniors are developing the condition. In most cases, the population’s educational attainment has risen, boosting more seniors’ ”cognitive reserve” — and with it their ability to ward of the disabling effects of age-related changes to the brain.

The commission found that stunted educational attainment — specifically, the failure to complete more than eight years of school — is childhood’s most potent risk factor for developing dementia. This alone is responsible for 8% of one’s lifetime risk for the disease. That makes lack of education a more powerful driver than the ApoE-e4 gene variant, which predisposes carriers to dementia and is estimated to be responsible for 7% of its incidence.

The Lancet Commission’s report, unveiled at the Alzheimer’s Assn.’s International Conference in London, followed the presentation of four separate studies showing that stresses that begin in early childhood severely impair brain health in later life. Those stresses — including poverty, family fractures, and poor prenatal healthcare — and their cognitive effects are disproportionately seen in African Americans, the studies found.

In midlife, the commission found that one of the most powerful — and fixable — drivers of dementia risk is hearing loss. In fact, as much as 9% of lifetime risk for dementia lies with hearing loss during midlife. The impact of addressing this would dwarf the benefits that could come from other modifiable midlife risk factors, such as managing high blood pressure (which contributes 2% of lifetime risk) or reducing obesity (1% of lifetime risk).

Recent news about dementia — and about the most common form of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease — has focused heavily on a string of dashed hopes as pharmaceutical researchers shoot for a cure.

But Schneider said the commission’s report sounds a hopeful note, recommending not just ways to reduce dementia rates but how best to care for those who have it.

The commission calls for dementia care that is tailored to individuals. This should include medication and other treatment for cognitive symptoms and a reliance on social and psychological solutions for problems such as agitation, low mood and psychosis.

It also calls for widespread supports for family caregivers, who bear most of dementia’s burdens.

ALSO

U.S. researchers are trying a series of life hacks to try to ward off dementia

Worried about dementia? Hearing and language problems could be forerunners of cognitive decline