The U.S. should rethink its entire approach to painkillers and the people addicted to them, panel urges

The report said some who are dependent on painkillers will turn to street drugs such as fentanyl and heroin. (July 14, 2017)

To reverse a still-spiraling American crisis fueled by prescription narcotic drugs, a panel of experts advising the federal government has recommended sweeping changes in the ways that physicians treat pain, their patients cope with pain, and government and private insurers support the care of people living with chronic pain.

In a comprehensive report on what must be done to staunch the toll of opiates in the United States, a panel of the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine makes clear that steps needed to prevent the creation of future opiate addicts will drive some people who are now dependent on these medications toward street drugs such as fentanyl and heroin.

“It is therefore ethically imperative to couple a strategy for reducing lawful access to opioids with an investment in treatment for the millions of individuals” already hooked on the painkillers, the panel wrote.

Even as lawmakers in Washington debate a healthcare bill expected to reduce access to addiction treatment, the expert panel called on states and the federal government to provide “universal access” to such treatment in hospitals, community-based programs, jails and prisons.

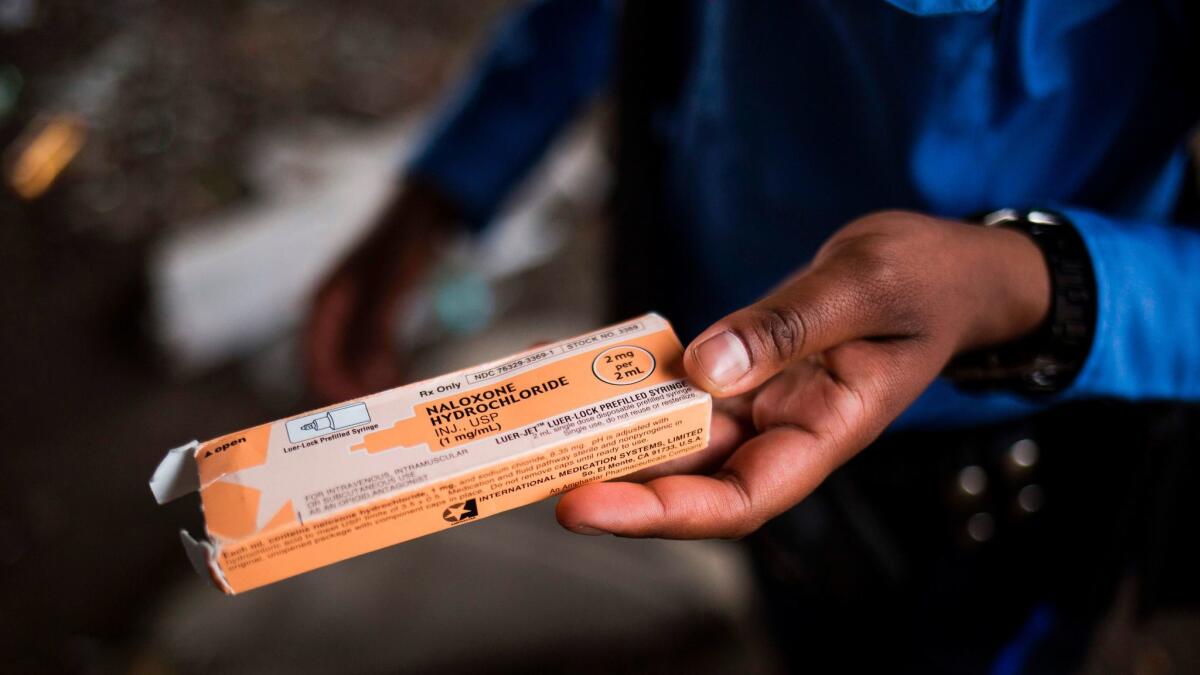

To reduce harms to opioid users who have turned to the streets for their supply, the panel also urged states to buck a current trend of getting tough on illicit drug use. Instead of escalating criminal penalties for drug-related behaviors, the panel said states should adopt practices — including needle exchanges, safe havens for injection-drug users, and broadened access to the opioid-reversal agent naloxone — that reduce overdose deaths and prevent the spread of disease.

In 2015, some 2 million Americans were thought to be abusing prescription narcotics. Another 600,000 were using heroin, the majority of them onetime prescription opiate users. The report cites research suggesting that, among patients prescribed opioid pain relievers, at least 8% develop “opioid use disorder” and 15% to 26% engage in problematic behaviors that suggest they have become dependent.

“The numbers are extraordinary and unfortunately it’s still getting worse,” said Richard J. Bonnie, chairman of the panel and director of the University of Virginia School of Law’s Institute of Law, Psychiatry and Public Policy.

“We have a habit in our country of noticing certain problems … and then moving on to something else,” Bonnie said. But even with the kind of sustained, “all-hands-on-deck” approach required, the opioid drug epidemic, more than two decades in the making, “will take some significant period of time to unwind,” he added.

Dr. Leana Wen, health commissioner for the city of Baltimore, said the new report’s recommendations are “hard to argue with, because they are comprehensive and evidence-based.” But Wen, who has been an outspoken voice for broader access to addiction treatment, said she had hoped for less fretting over incomplete research findings and more focus on how to expand treatment services.

“We already know what works,” she said. While more could be understood about the biology of addiction, “we do not need more studies” to justify expanded treatment programs. “We do not more rhetoric. We need the resources to get us there.”

The report released Thursday was requested and underwritten by the Food and Drug Administration, an agency whose approach to regulating opioid painkillers would come in for some strong medicine under the panel’s recommendation.

The panel of independent experts proposed that in assessing the safety of prescription opioid drugs for the U.S. market, the FDA consider risks not just to the patients taking them, but also to their families and communities.

New formulations of opioid medications should be subject to that higher standard, the panel said. In addition, manufacturers of those drugs should be required to conduct extensive studies of their products’ use after FDA approval, and the agency should reevaluate their safety one, four, and six years after their entry onto the U.S. market.

Once the FDA has established new standards for evaluating the safety of proposed new opioid products, it should reassess all opiate medications currently on the market according to the same requirements, the committee said.

Panel members said that while imposing that “exceptional” standard on opioid medications represents an expansion of current practice, the FDA already has the power to broaden and expand its regulatory practices for certain risky drugs.

The numbers are extraordinary and unfortunately it’s still getting worse.

— Richard J. Bonnie, chairman of the panel that produced the new National Academies report

Many of the panel’s proposals are likely to fly into political headwinds. President Trump has called the crisis of opioid addiction one of his administration’s top priorities, and established a commission, chaired by New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, to formulate federal responses.

But with that commission’s report incomplete, Trump and his congressional allies are pursuing a wide range of policies that would appear to conflict with those identified by the National Academies panel as needed to stem the epidemic.

In its first months in office, the Trump administration has moved to reduce funding for a wide range of biomedical research and to slash regulations at the FDA. The National Academies report both proposes new layers of FDA regulation for opioid drugs and calls for expanded research on pain processes in humans, on factors that contribute to addiction vulnerability and treatment success, on prescribing practices, and on opiate use patterns and their consequences.

On Capitol Hill on Thursday, Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky unveiled a healthcare bill that would scale back public funds for addiction treatment. The new bill also would give insurance companies more latitude to offer consumers low-cost policies stripped of services such as treatment for addiction for mental health, or that transfer to customers the cost of services such as non-drug therapies for pain.

The National Academies report underscores that if more of the nation’s 2.6 million people with opiate-use disorders are to get treatment, it must be made more accessible.

The panel added that for most chronic pain not associated with cancer or end-of-life care, non-drug therapies — including exercise and physical therapy, psychotherapy, acupuncture and chiropractry — offer effective relief without the risk of addiction. But it acknowledged that, compared to the price of a prescription, such treatments can be costly, and insurers have long been reluctant to pay for them.

Dr. Mark Schumacher, a panel member who chairs UC San Francisco’s pain medicine division, said the panel concluded that “misaligned incentives” — such as policies that allow insurers to shift the costs of non-drug therapies to patients — are currently limiting the use of these safer alternatives.

Efforts to educate medical professionals about non-drug approaches to pain, meanwhile, are “inadequate and under-resourced,” Schumacher said.

“These tools are not being used to their full potential,” he said.

Dr. Joseph Frank, a primary care physician at Denver’s Veterans Affairs Medical Center, said the new recommendations underscore that “the best physicians should not be providing pain treatment on their own.” Providing the full range of treatment endorsed by the National Academies panel would mean a primary care doctor has established ties to acupuncturists, physical therapists and psychotherapists, said Frank, who teaches at the University of Colorado and was not involved in the new report.

“The question is one of availability — do these people practice in your community, and, if they do, are they affordable?” he said.

The new report chronicles the surge of opioid painkiller use starting in the early 1990s, as new and aggressively marketed formulations of opioid painkillers came to the market, and physicians armed with those drugs became more responsive to patients’ complaints about pain.

Sales of the powerful prescription opiate OxyContin rose from $48 million in 1996, a year after it was approved by the FDA, to more than $1 billion by 2000. And between 1999 and 2010, sales of prescription opioids grew fourfold.

As physicians prescribed more — and more powerful — narcotic pain relievers to more patients for more conditions over a longer period of time, overdose deaths linked to opiates tripled between 1990 and 2015.

The new report acknowledges the role both of doctors and drug companies in expanding the use of opioid medications over the past 25 years. For drug companies, the panel focuses heavily on tighter regulation. For physicians, nurses and dentists — most of whom accepted industry-backed claims that opioids could treat pain without much risk of addiction — the panel prescribes a strong dose of reeducation.

Updates on opioids should probably not come from the manufacturers of the drugs, who have traditionally taken a leading role in “detailing” doctors, dentists and their staffs on the proper use of their products, said Dr. Aaron S. Kesselheim, a panel member from Harvard Medical School’s Center for Bioethics.

“Overzealous promotion and financial relations between pharmaceutical manufacturers and physicians through the ’80s and ’90s and 2000s has clearly been shown to be a contributor to overprescribing,” Kesselheim said. To ensure that opioids’ many risks are properly communicated to doctors and their staffs, “we need to think about ways to ensure that educational practices are done independent of manufacturers,” he added.

New messages about the risks and benefits of available treatments will also be needed for patients with chronic pain, the panel said. It urged the U.S. Surgeon General, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, professional organizations and heads of major foundations to huddle over how best to communicate the limitations of opioids and the possible benefits of alternatives including ibuprofen and talk therapy.

Twitter: @LATMelissaHealy

MORE IN SCIENCE

Surgery for early-stage prostate cancer does not lead to longer lives, study finds

Who needs film when you can store a movie in bacteria DNA?

UPDATES:

6:40 p.m.: This story has been updated with additional commentary and new information throughout.

This story was originally published at 10:55 a.m.