Coronavirus Today: Is the end finally in sight?

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Feb. 7. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

After three long years, here are the words you’ve been waiting for: The days of the public health emergency are numbered.

As far as the federal government is concerned, the health emergency that began Jan. 27, 2020, will end May 11. That’s in 93 days.

In California, the COVID-19 state of emergency will wrap up Feb. 28. That’s just three weeks away.

If you’ve lost patience with all things pandemic, head to Los Angeles. As of Wednesday, the city’s emergency declaration is over (though one for L.A. County remains in place).

Of course, none of this means the coronavirus is gone. Nationwide, there were at least 280,911 new infections reported over the past week and 3,452 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. If the pandemic could be ended by signing a piece of paper, this whole mess would have been over a long time ago.

It’s not the disease outbreak that’s ending but the public health emergencies it spawned. To understand the difference, let’s take a look at what will change when those emergencies come to an end.

COVID-19 vaccines and treatments: These will remain available at no cost — for a while.

“On May 12, you can still walk into a pharmacy and get your bivalent vaccine. For free,” Dr. Ashish Jha, the White House COVID-19 response coordinator, explained in a Twitter thread. “On May 12, if you get COVID, you can still get your Paxlovid. For free.”

But sometime during the summer or early fall, this will cease to be the case. Healthcare providers will get COVID-19 vaccines and medications the way they get other pharmaceutical items. Most people with health insurance will be able to get booster shots without paying out of pocket, and Jha pledged that Paxlovid will be both “accessible and affordable.”

The California Health and Human Services Agency was more explicit about what to expect.

State residents with private health insurance or Medi-Cal “can access COVID-19 vaccines, testing and therapeutics from any appropriately licensed provider without any out-of-pocket costs” until Nov. 11, the agency said. After that date, COVID-19 care will continue to be freely available to those who seek care from an in-network provider. If they go outside their network, they may find themselves having to pay.

Coronavirus tests: State-run COVID-19 testing sites will get harder to find. The Department of Public Health will begin closing down testing sites that are “underutilized.”

“These sites were an important part of the state’s COVID-19 testing strategy and response,” the department said. “A final plan for demobilizing the remaining sites is being prepared.”

Barbara Ferrer, Los Angeles County’s director of public health, said county-run testing sites will remain open as long as there is sufficient demand for them. There will be changes in the way things are paid for, but those haven’t been worked out yet, she said.

At-home tests will still be available, but you may have to start paying for them. The rule requiring health insurers to reimburse the cost of up to eight tests per customer per month will go away when the public health emergency is over. But if you live in California and have an insurance plan regulated by the state Department of Managed Health Care, you can keep getting reimbursed up to $12 per test for up to eight tests per covered person per month, per a law passed in 2021.

Emergency use authorizations: These will expire when the federal public health emergency ends. After that, vaccines, antivirals, devices and other treatments invented to fight COVID-19 will be available only if they’ve received full approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Right now, that’s a pretty short list. Remdesivir, the first antiviral developed specifically for COVID-19, is on it, as are two medications for hospitalized adults who need supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation or ECMO (tocilizumab and baricitinib). That’s it.

The FDA is reviewing Pfizer’s application to grant full approval to Paxlovid.

The original version of Comirnaty, the COVID-19 vaccine from Pfizer and BioNTech, has full FDA approval as a primary immunization series for those age 12 and up. All other uses — including in younger children and as a booster shot — are governed by emergency use authorizations, as is the updated formulation that targets the Omicron variant.

The situation is similar for Spikevax, the original version of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine. It is fully approved as a two-dose primary series for those 18 and up. All other uses of this vaccine and its new bivalent sibling are made possible by EUAs.

The COVID-19 vaccines from Novavax and Johnson & Johnson are not FDA-approved in any form.

Medicaid enrollment: Millions of people who are enrolled in the health insurance program for disabled and low-income Americans are expected to lose their coverage.

One of the country’s first major pandemic response laws injected extra money into state Medicaid programs. States that accepted the money weren’t allowed to drop people from their rolls as long as the health emergency was in effect. But now they can.

People who moved to a new state during the pandemic or saw their incomes rise above the threshold may have to find pricier insurance. Some states are planning to force all Medicaid beneficiaries to re-enroll; people who don’t deal with the paperwork hassle in time will lose their coverage.

Researchers at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute estimate that at least 6.7 million children risk being knocked off Medicaid rolls in the first year after the health emergency ends.

Emergency logistics: The city of Los Angeles has already deactivated its emergency operations center, though it can be reactivated quickly if coronavirus conditions worsen.

Ending the state’s health emergency will mean removing the legal basis for dozens of COVID-related executive orders issued by Gov. Gavin Newsom. (Many of those have been terminated already.) Newsom hopes to make two of his executive orders permanent by codifying them into state law: One would allow nurses to keep ordering COVID-19 medications for patients, and the other would let lab workers process coronavirus tests full-time.

What will not change: The coronavirus will still be out there. It will still be making people sick, and some will die.

“The states of emergencies — a lot of that is about how to do things faster, how to free up funds faster, but it doesn’t have to do with what the virus is doing because it’s still circulating,” said Dr. Sara Cody, Santa Clara County’s public health director and health officer.

“The pandemic is not over,” she added. “We can’t declare a day when it’s over, and as we’ve seen, it’s having a very, very long tail. We don’t know when it’s going to be over.”

By the numbers

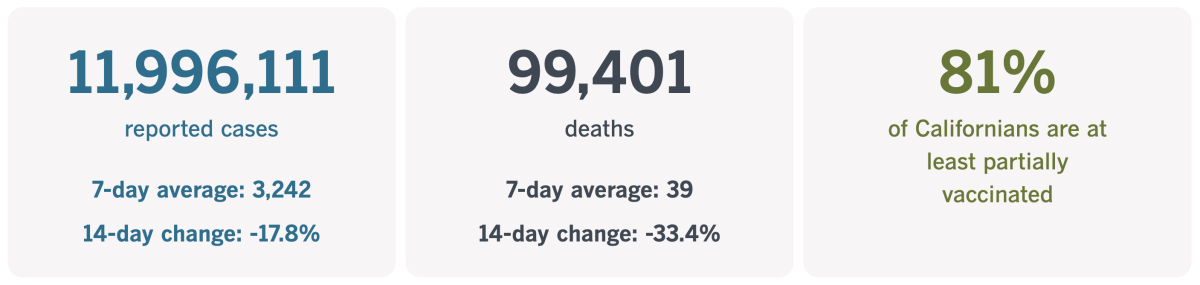

California cases and deaths as of 4:30 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Hello COVID-19, good-bye rat race

Did the pandemic turn China’s young adults into slackers?

In Chu Fei’s case, it prompted her to reevaluate her priorities. The Peking University and Stanford alumna quit her demanding job at a major tech firm, sold most of her stuff and moved to a scenic village about 800 miles from her former home in Beijing.

Now she spends her days writing, creating videos and managing an ecommerce venture. The leisurely pace is a far cry from the 12-hour workdays she left behind in the big city.

“I think COVID gave me a chance to really reflect on myself,” Chu told my colleague Stephanie Yang.

Her striving lifestyle had been taking a toll even before the pandemic prompted onerous lockdowns and the country’s economy stalled. But the worse things got, the less motivated she became. She was 30 when she decided to try something different.

“It just felt like my plan wouldn’t work anymore,” she said.

She’s not the only one. The number of freelancers, part-timers and other flexible workers in China nearly tripled in 2021, ending the year at 200 million, according to the country’s National Bureau of Statistics. And more want to join them: A survey of workers last year found that 73% were interested in becoming digital nomads.

Experts say it’s a sensible reaction to China’s economic slowdown. Tech companies used to inspire a work ethic known as “996” — working from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week — but widespread layoffs and reduced social mobility have made that grueling pace a lot less appealing.

“It’s basically an economic problem,” said Terence Chong, an economics professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “Young people, they think they have no hope, housing prices are so expensive, so they just limit how hard they work.”

And when they are working, they’re increasingly doing so on their own terms, with more flexibility in their hours and locations.

Younger workers “are experimenting with different ways of living,” said Zhan Yang, a cultural anthropologist at Hong Kong Polytechnic University. “It’s like a small social experiment is taking place in China.”

This way of thinking isn’t exactly endorsed by the Communist Party, which would prefer to see China’s young adults establish their careers, get married, buy a home and have children.

“Work is most glorious, our happy lives are created through work,” President Xi Jinping said in June while visiting a university in Sichuan province.

If you ask Chu, she’ll tell you she’s happy with the unconventional life she’s created. Her new digs are in a villa that was a hotel before the pandemic. Neighbors in her adopted village grow vegetables and tea, and she marvels that the night air smells sweet.

Between her savings and the money she makes from entrepreneurial pursuits, Chu thinks she can live this way for a few years while she figures out a long-term plan. One thing she knows for sure: She isn’t going back to the way she used to live in Beijing.

“There’s kind of a feeling, like, what have I done for all these years? I’ve wasted so much time,” she said. “I can say I went to some good universities and worked at some big companies, but it’s not something you want to write on your tombstone, you know?”

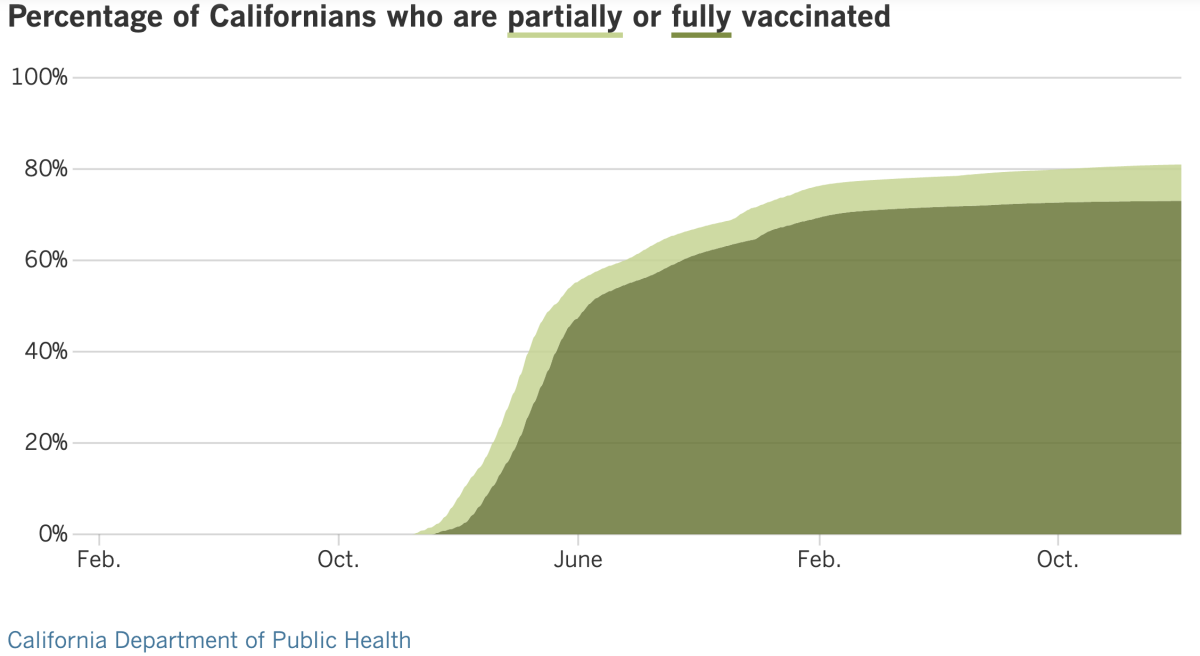

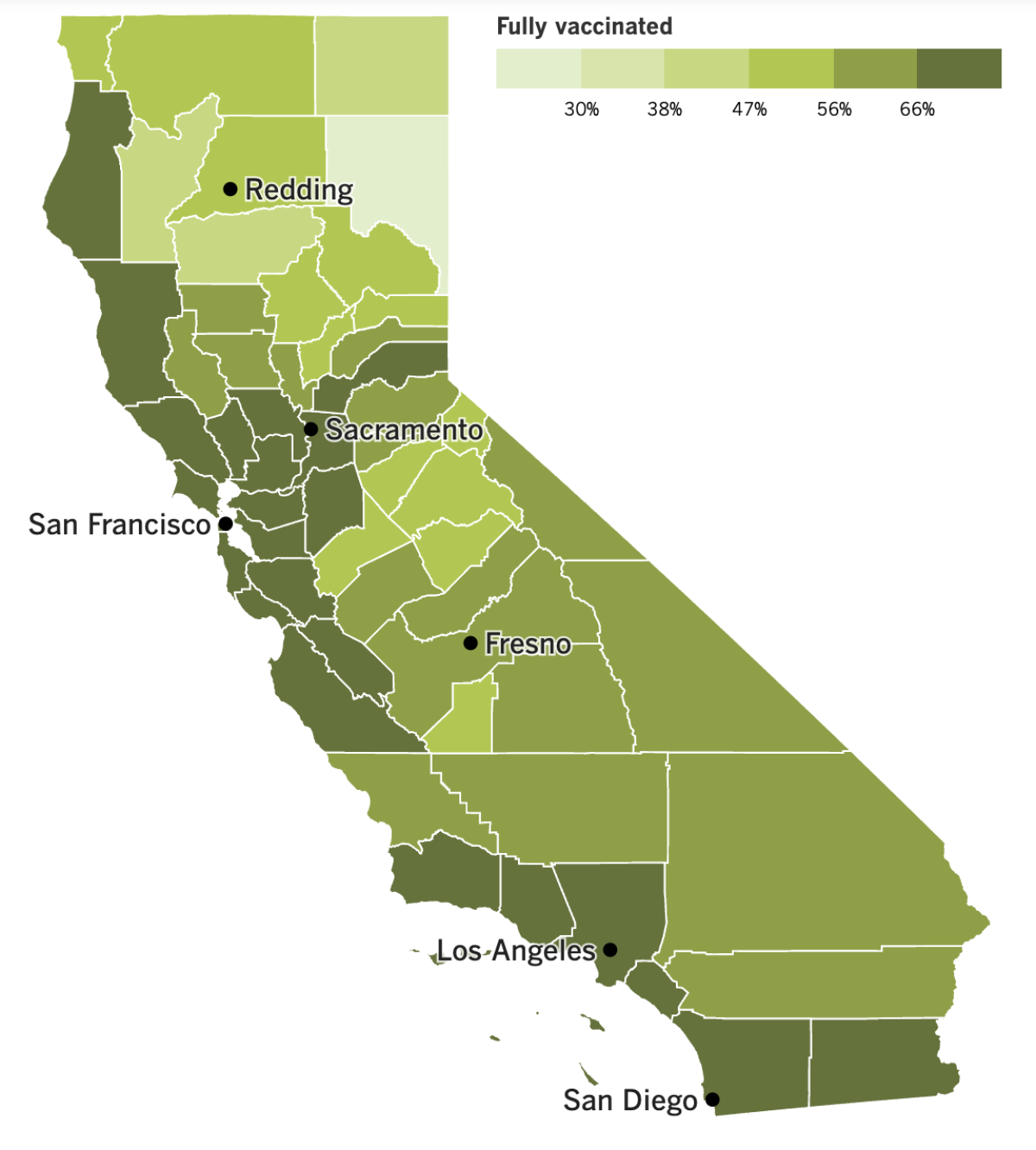

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

California’s public health emergency is in effect for three more weeks, but some of the state’s anti-COVID policies are already falling by the wayside.

Health officials in Sacramento acknowledged last week that they have quietly dropped the COVID-19 vaccine mandate for K-12 students. The policy change was so stealthy that officials at the California Department of Public Health won’t even say when the decision was made.

“CDPH is not currently exploring emergency rulemaking to add COVID-19 vaccinations to the list of required school vaccinations,” the department said in a statement.

The policy was considered groundbreaking when Newsom announced it in October 2021. The governor anticipated that when COVID-19 vaccines became available for students of all ages, the mandate would apply to 6.7 million kids attending public or private schools. The initial date for the policy to go into effect was July 1, 2022, but that was delayed one year to give the FDA time to grant full approval for kid-size doses of the shots.

Since the policy has been on hold for months, the decision to abandon it will have little practical effect. Besides, the mandate would have come with a loophole so big — a lenient personal-belief exemption — that it would have been difficult to enforce. Only the state Legislature could have closed that loophole, but a bill to make that happen was withdrawn last year.

The city of Los Angeles is also relaxing a vaccine mandate, this one aimed at city employees. The mandate is still in place, but thousands of workers who requested religious or medical exemptions will be getting them approved, no questions asked.

The change was detailed in a memo by Dana Brown, general manager of the city’s personnel department. It applies to roughly 4,900 exemption requests submitted by Jan. 31. Requests filed after that date will be reviewed “on an individual basis and processed according to the Vaccine Exemption Procedures,” according to the memo. That’s the standard that previously applied to all exemption requests, which gave the city a chance to ensure they were valid.

To give you an idea of the effect of this change, consider this: Only nine of the 335 exemption requests filed by L.A. Fire Department employees were granted before the policy was amended. (Firefighters and police officers challenged the vaccine mandate in court but lost.)

The policy change was approved in late January by a committee of four members of the City Council plus L.A. Mayor Karen Bass. The full council, which approved the vaccine mandate in 2021, did not have a say.

Yet another rollback came courtesy of a federal judge in California who has temporarily blocked enforcement of a controversial law intended to stop doctors from giving patients false information about COVID-19.

The law, known as AB 2098, is only a few weeks old but has already been subject to legal challenges. Children’s Health Defense, a nonprofit peddler of inaccurate health information founded by vaccine skeptic Robert F. Kennedy Jr., is among the plaintiffs suing to block the law. So is a Newport Beach doctor who has promoted the discredited COVID-19 treatments ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine.

AB 2098 is also opposed by some pro-vaccine doctors, as well as the ACLU of Northern California.

“We can all agree that if doctors are spreading COVID misinformation deliberately, that’s a problem,” said Hannah Kieschnick, a staff attorney for the civil liberties organization. But she said AB 2098 “is unconstitutional, unnecessary and risks pretty severe unintended consequences.”

The law empowers the Medical Board of California to discipline doctors who spread false information about COVID-19 on the grounds that doing so amounts to “unprofessional conduct.” Its original version gave specific examples of the type of conduct that would qualify as unprofessional, but the final version was vague. That makes it difficult for doctors to know what they can say without running afoul of the law, Judge William Shubb of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of California wrote in granting the preliminary injunction.

Dr. Donaldo M. Hernandez, president of the California Medical Assn., said he was “disappointed” in the ruling.

“AB 2098 applies only when a physician intentionally misleads a patient under their care or deviates from the appropriate standard of care,” Hernandez said in a statement. “It does not stifle legitimate, needed and appropriate scientific and medical debate. We cannot let the toxicity of the moment blind us to the moral and ethical obligations physicians have to our patients.”

Meanwhile, the latest COVID-19 community level map from the CDC shows signs of backsliding in California.

Last week, only the two counties along the border with Mexico — San Diego and Imperial — were in the “medium” category. This week, they’ve been joined by Merced, Stanislaus, Tuolumne and Mariposa counties in the central part of the state, along with Placer, El Dorado, Sacramento, Yolo, Solano, Napa and Lake counties to the north.

Los Angeles County remains in the “low” category. The number of coronavirus cases here dropped 10% week-over-week, while deaths fell 16%. Orange, Ventura, Riverside and San Bernardino counties also retained their “low” status, though case counts ticked upward in all except San Bernardino, according to the CDC.

And finally, data from the California Department of Health Care Services show that prescriptions for lifesaving hepatitis C medications dropped dramatically after the onset of the pandemic.

Hepatitis C is a liver infection that can cause liver cancer, cirrhosis and even death. It can usually be cured by taking antiviral medications for a few months, and the state has been working to make it easier for patients to obtain the pills through Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program.

Despite this, the number of people getting the treatment dropped 40% statewide between 2018-19 — the last full fiscal year before the pandemic — and 2020-21. It remained flat the following year before showing signs of improvement in the current fiscal year.

In L.A. County, prescriptions for hepatitis C drugs plunged nearly 58% between 2019 and 2021, according to an analysis by researchers at USC and the county Department of Public Health. As with the state as a whole, prescriptions rose somewhat last year but are still well below their pre-pandemic levels.

“There’s now a lot of people over the past three years of the pandemic who have forgone treatment, and no one is reaching out to them,” said Dr. Jeffrey Klausner, an infectious diseases expert at USC who worked on the analysis.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: When should I get my second bivalent booster shot?

This has been asked by multiple readers, and I’d like to commend them for being among the 15.7% of Americans who received a first dose of the new booster. Real-world data shows that people who got the Omicron-targeting shot were less likely to come down with COVID-19 and less likely to be hospitalized if they became sick.

Those shots became available in September, so for some people, it’s been five months since they’ve rolled up their sleeves. In the past, the FDA and CDC have advised Americans in certain high-risk groups due to age or other health conditions to boost after that amount of time. But as of this moment, there is no specific plan to offer a second dose of the bivalent booster.

The FDA recently proposed offering a COVID-19 shot that’s adjusted each year to match the most prevalent version (or versions) of the coronavirus. Most Americans will need to boost once a year, which means it’ll be awhile before most of the already-boosted will get another dose.

Some people — such as adults with weakened immune systems and very young children — may benefit from more frequent boosting. Experts are keeping a close eye on COVID-19 hospitalization data and other metrics to figure out who might fit in this category and when any extra shots should be offered. It’s not clear how soon they’ll figure this out, but we promise to keep you posted when they do.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

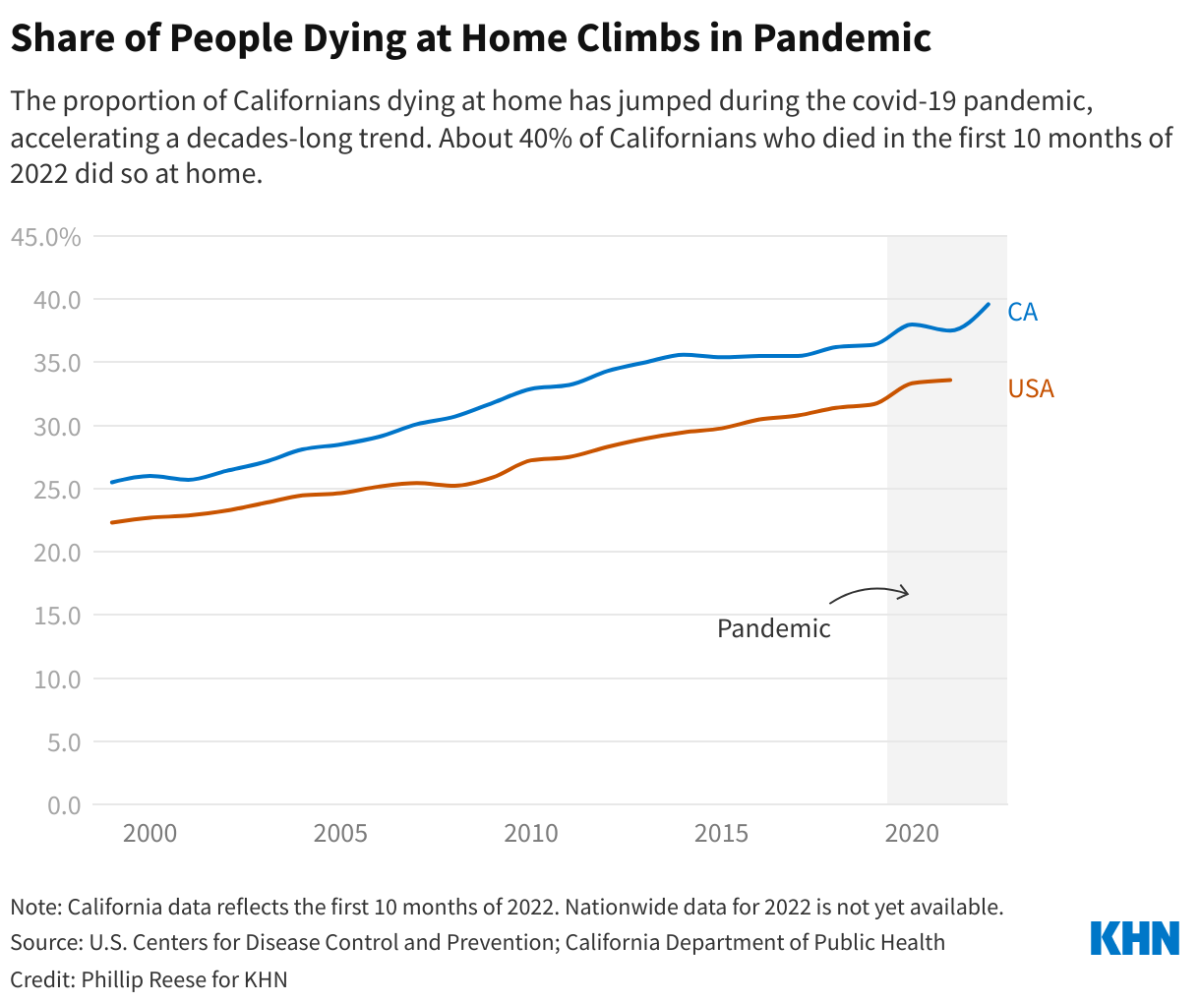

This week’s picture is a little different from our usual fare. It’s a graph that highlights an unsung trend of the pandemic: More Californians are choosing to die at home instead of in a hospital or nursing home.

The blue line represents people who died in California, and its slope makes clear that the percentage of deaths recorded in homes has been climbing steadily since the early 2000s. That long-term trend accelerated after the coronavirus arrived on the scene, our friends at KHN report.

Initially, it may have been chalked up to fear of going to hospitals brimming with COVID-19 patients. Another factor was the strict prohibition against visiting relatives in nursing homes, which prompted some families to bring their loved ones home.

But the rise in home deaths outlasted the lockdown period and continued well after COVID-19 vaccines made people less afraid of the virus. Nearly 40% of Californians who died between January and October 2022 did so at home, up from 36% for all of 2019. That’s an increase of 11%. (Available data suggest the trend has been similar for the country as a whole, though to a lesser extent.)

People who provide end-of-life care say they’re not surprised to see more people embracing the idea of spending their last days in familiar, comfortable surroundings.

“Whenever I ask, ‘Where do you want to be when you breathe your last breath?’ or ‘when your heart beats its last beat?’ no one ever says, ‘Oh, I want to be in the ICU’ or ‘Oh, I want to be in the hospital’ or ‘I want to be in a skilled nursing facility,’” said John Tastad, who coordinates the advance care planning program at Sharp HealthCare in San Diego. “They all say, ‘I want to be at home.’”

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.