Coronavirus Today: A sobering setback

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Jan. 31. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

For months now, almost everything about the pandemic seemed to be getting better. Sometimes that progress came in fits and starts, but the momentum was moving in just one direction — toward the day when we can safely treat COVID-19 like any other infectious disease.

Then along came a sobering reminder of how hard it is to keep pace with the ever-changing coronavirus.

The message was delivered by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. On Thursday, the agency revoked its emergency use authorization for Evusheld, a workhorse drug that millions of Americans with weakened immune systems counted on to keep them from becoming severely ill if they came down with COVID-19.

Evusheld won FDA clearance back in December 2021. It’s a combination of two monoclonal antibodies — tixagevimab and cilgavimab — that can be injected directly into patients who have trouble making antibodies on their own, even after multiple shots of COVID-19 vaccine. With the drug giving them the protection they needed, they could finally leave the isolation of their homes and rejoin the world without putting their lives at risk.

Now that protection is gone.

“It’s a really sad time,” Dr. Camille Kotton, a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, told my colleague Melissa Healy. For her patients with impaired immunity, the loss of Evusheld “was kind of like being told the seat belts in your car won’t work anymore, and we’re not going to be able to replace them with anything.”

Evusheld’s demise comes courtesy of the Omicron variant, the most wily iteration of the coronavirus to date. Nine Omicron subvariants — including XBB.1.5, BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 — contain mutations that allow them to evade the protection the drug is supposed to provide.

Unfortunately, those nine subvariants collectively account for more than 90% of the coronavirus specimens now circulating around the country, according to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. With the odds stacked so heavily against Evusheld, the FDA had no choice but to withdraw its emergency use authorization.

Evusheld could be reinstated if the proportion of resistant variants falls below 90% in the future, the FDA said. But at the moment, that doesn’t look likely. That means a medication that cost taxpayers at least $1.58 billion to develop and produce became obsolete in just over a year.

It’s hardly the only anti-COVID drug to be rendered useless by genetic changes in the coronavirus. The Delta variant was the first to knock out a monoclonal antibody therapy, and Omicron wiped out most of the rest. Out of seven antibody treatments that were once authorized by the FDA, only one — tocilizumab — is still available, though only for severely ill patients who are being treated in a hospital.

The loss of these antibody therapies is particularly dire in light of the fact that many people with weak immune systems can’t take Paxlovid because it would mess with other medications they take. That leaves them with two subpar alternatives: molnupiravir, an antiviral that’s less effective than Paxlovid, and remdesivir, which requires three days of infusions, typically in a hospital.

All of this adds up to a huge step backward for the roughly 7.2 million American adults who are immunocompromised. They are people undergoing treatment for cancer; people who take medication to prevent their immune systems from rejecting transplanted organs; people with autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis; and people who have lost critical T cells to untreated or advanced HIV, among others.

Evusheld was supposed to be administered to patients once every six months. But some people got only one dose before the drug lost its effectiveness. Some never got it at all.

“We’re mourning the official death of what had been a really good tool,” Kotton said.

We’re not going to get out of this pandemic by letting setbacks derail our progress. AstraZeneca, the company that makes Evusheld, said Friday that it is already working on a new antibody drug for people with weakened immune systems. The pharmaceutical giant hopes the new drug will be ready by the end of the year.

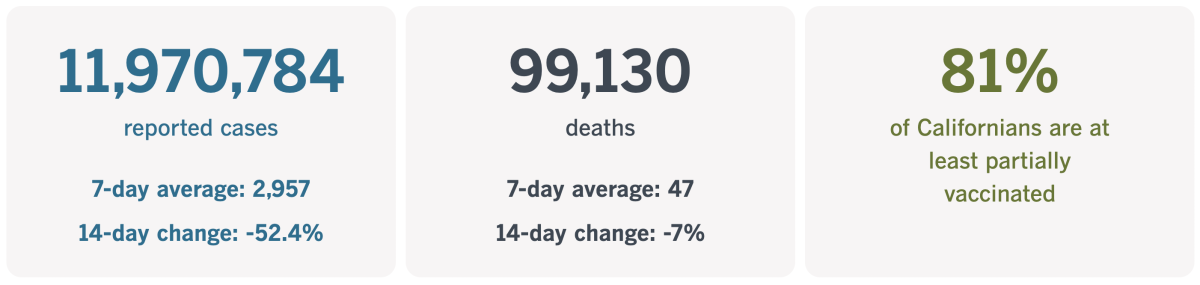

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 5:15 p.m. Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Putting a price on COVID-19 vaccines

The latest figures from the CDC show that just 16.5% of Americans 5 and older have received the latest COVID-19 boosters, which came out in September and are specially formulated to recognize the Omicron variant. Considering that the vaccines are credited with saving millions of lives (not to mention more than $1 trillion in healthcare costs in the U.S. alone), it’s clearly in our best interests to make it as easy as possible for people to get them.

The mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna are about to get more expensive. Will that make the shots more accessible, or will it have the opposite effect?

If you’ve ever taken a course in basic economics — or if you have a modicum of common sense — you know the answer is a no-brainer: Raising the price of COVID-19 vaccines will mean fewer people can afford to get them.

The price increase we’re talking about is substantial. The federal government bought 1.2 billion doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, paying an average of about $20.69 for each, according to estimates by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

But Congress has stopped appropriating money for pandemic essentials such as vaccines. Soon, the companies will be selling their vaccines directly to healthcare providers and negotiating prices with insurance companies. Both Moderna and Pfizer have said they plan to charge between $110 and $130 per dose. That’s an increase of 432% to 528%.

Most Americans wouldn’t pay the full sticker price. In fact, if they have health insurance, they probably wouldn’t hand over any cash when they roll up their sleeves. (That’s thanks to the Affordable Care Act, which incentivizes preventive care.)

But they would pay the higher price indirectly, through heftier insurance premiums. And people who are uninsured or underinsured could be in for some sticker shock.

As my colleague Michael Hiltzik reports, the companies have defended their price increases by invoking the huge savings made possible by their vaccines.

The Pfizer vaccine, Comirnaty, and the company’s antiviral pill Paxlovid have “saved hundreds of thousands of lives [and] tens of billions of dollars in healthcare costs,” a Pfizer spokesman told Hiltzik. The company “has priced the vaccine to ensure the price is consistent with the value delivered,” the spokesman added.

A Moderna spokesman echoed that theme: “Moderna is committed to pricing that reflects the value that COVID-19 vaccines bring to patients, healthcare systems and society,” he said.

Hiltzik questions why the companies should get to decide how much of those savings should be steered their way — especially since the mRNA vaccines were made possible by taxpayer-funded basic research. Moderna also received a direct grant from the federal government’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority worth nearly $1 billion.

“It’s impossible to overstate the moral depravity of this argument,” Hiltzik wrote.

Indeed, he questions why the two companies need to raise their vaccine prices at all.

Oxfam International, a nonprofit devoted to fighting poverty, used a report by experts from Imperial College London to estimate that Pfizer’s vaccine could be produced for as little as $1.18 per dose, while Moderna’s vaccine could be made for $2.85 per dose. Even if the companies held their price steady at $20.69, their profit margins still would be enviable.

Since federally funded research helped bring mRNA vaccines to fruition, the government has the authority to influence their prices under the Bayh-Dole Act. Among its provisions are “march-in rights,” which allow the government to take action if a company that licensed taxpayer-funded research fails to roll out its product on “terms that are reasonable.”

The feds have threatened to use their march-in rights in the past but have never followed through. But there’s a first time for everything — and given the critical importance of COVID-19 vaccines, perhaps this will be it.

“Few drugs on the market today can match their capacity to advance public health and few may be as sensitive to the level of price increases planned by Moderna and Pfizer,” Hiltzik writes. “This is a subject on which the federal government cannot and should not remain silent.”

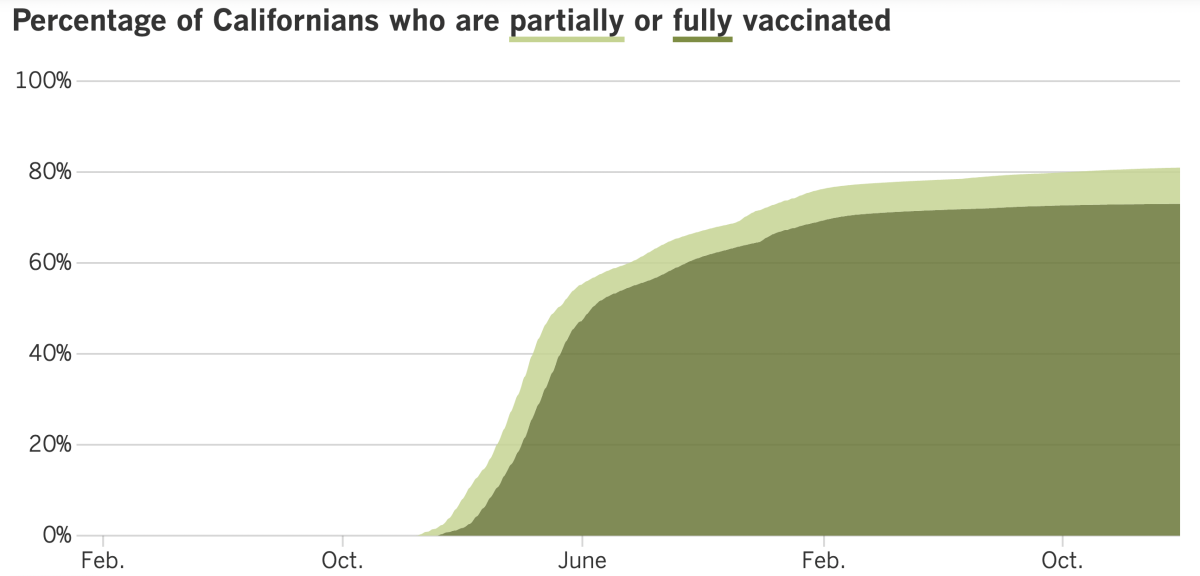

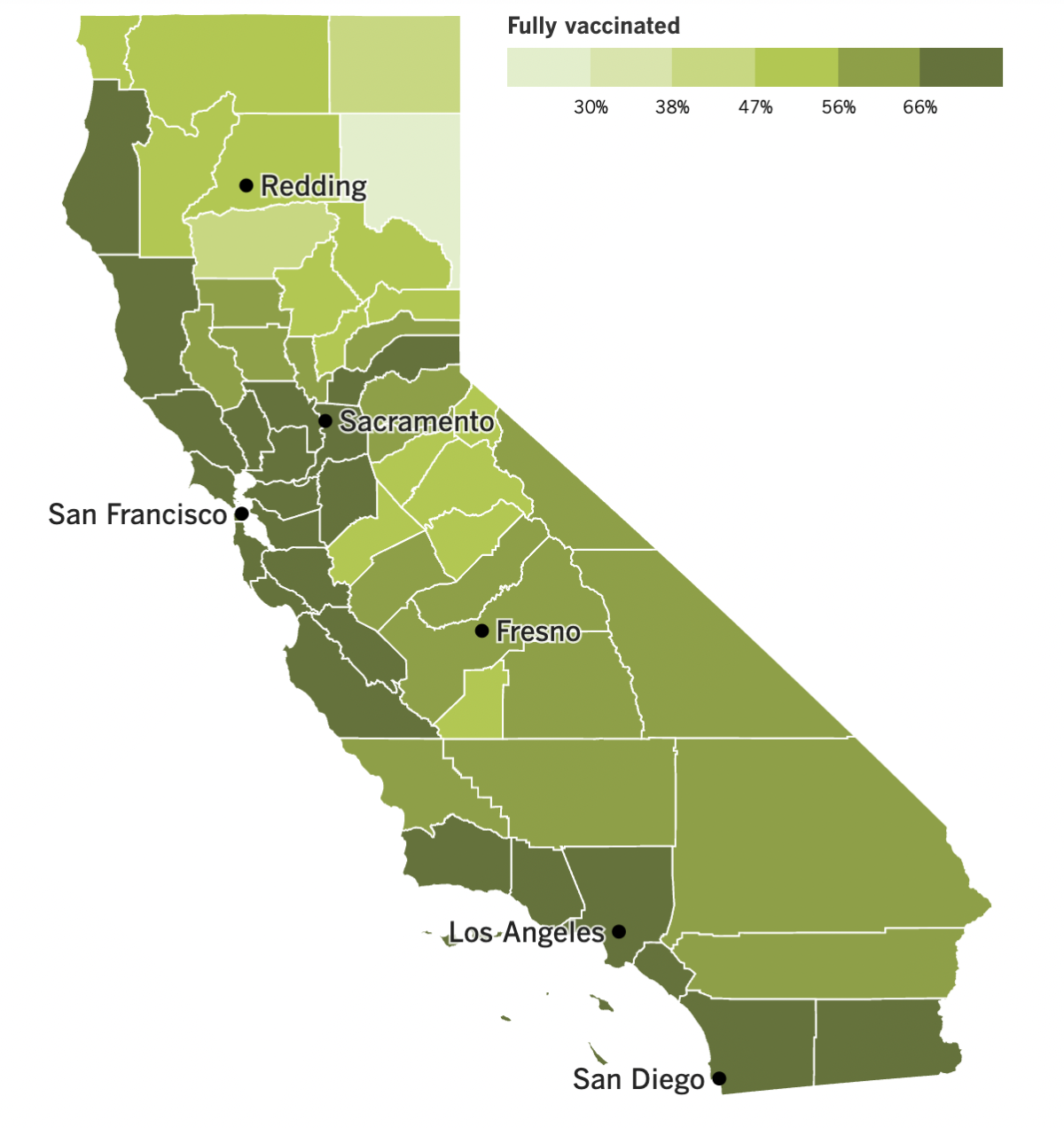

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

Friday was the third anniversary of Los Angeles County’s first confirmed coronavirus infection. Barbara Ferrer, the county’s public health director, marked the occasion by sharing some indisputably good news.

The nation’s most populous county is now averaging fewer than 1,000 official cases per day. (As of Tuesday, that figure is around 931.) What’s more, viral levels detected through wastewater surveillance have fallen sharply in recent weeks.

“These numbers confirm that the decline in transmission is both real and significant,” Ferrer said.

L.A. continues to have a low COVID-19 community level, with the number of cases dropping nearly 22% week-to-week, according to the CDC. (In fact, nearly the entire state of California is currently in the “low” category. The only exceptions are San Diego and Imperial counties, which are classified as “medium.”)

The number of COVID-19 deaths — about 136 countywide over the last week — is still too high. In early November, before the holiday season kicked into gear, the weekly death toll was 43. In early May, before the second Omicron surge began, there was a week with just 24 deaths.

Ferrer said she hoped “the decline in transmission will be followed soon by a decrease in deaths.” If we could maintain a rate of 35 COVID-19 deaths per week, that would be a sign that “our protections are really working extraordinarily well,” she added.

The recent progress is due to a combination of factors, Ferrer said, including COVID-19 vaccines, immunity from past infections, medicines that work, preventive measures such as wearing masks while inside crowded public spaces, and a willingness to stay home when a coronavirus test reveals an infection.

Indeed, local conditions have improved so much that the county amended its blanket recommendation for everyone to mask up inside grocery stores, libraries and other public settings. Instead, for most people, the decision about wearing a mask is now a matter of personal preference.

Ferrer said people who are at risk of developing a severe case of COVID-19 should continue to wear masks indoors, especially in places that are crowded or have poor ventilation. The same advice goes for people who live with someone who is vulnerable. Masks continue to be required for everyone while taking public transportation or spending time inside medical facilities or nursing homes.

Ferrer isn’t the only official feeling optimistic these days. President Biden told Congress on Monday that the nation’s public health emergency will end on May 11.

The health emergency was initially declared by then-President Trump on Jan. 31, 2020, and it’s been extended every few months since then. Trump also determined that the pandemic presented a national emergency on March 13, 2020; that will end on May 11 as well.

Once the emergencies are officially over — on paper, at least — the government will manage the coronavirus threat through its normal channels. Vaccines, tests and treatments will stop being free (though with pandemic funding running low and Congress unwilling to appropriate more, those things will have to stop being free anyway).

Those aren’t the only changes we’ll have to look forward to. All emergency-use authorizations granted by the FDA will stop being valid, so the only vaccines and treatments that will continue to be available are the handful that received full FDA approval. Hospitals will stop getting extra money to care for COVID-19 patients. Health insurance companies may stop paying for telemedicine visits. And millions of Americans could lose their health insurance altogether as protections for Medicaid patients fall by the wayside.

The World Health Organization has also been contemplating how much longer the public health emergency needs to last. After meeting with key advisors on Friday, the agency’s leaders determined that it’s still too soon to set an end date.

“There is no doubt that we’re in a far better situation now” than we were a year ago, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said Monday. But more than 170,000 people have died of COVID-19 over the last eight weeks, some countries are still struggling to get access to vaccines and medicines, and misinformation is undermining efforts to get the pandemic virus under control.

The end is not yet be in sight, but it may be soon. The WHO advisory committee said the pandemic “may be approaching an inflection point,” and Tedros agreed.

“We remain hopeful that, in the coming year, the world will transition to a new phase in which we reduce hospitalizations and deaths to the lowest possible level,” he said.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Is the risk of dying of COVID-19 still higher for unvaccinated people than for vaccinated people?

This question comes from a reader whose unvaccinated relatives insist that COVID-19 has become so mild that there’s no longer any need to get the shots. Those relatives may be surprised to hear that even three years into the outbreak, getting their initial doses now will still help — a lot.

As of late November, there were 1.79 COVID-19 deaths for every 100,000 unvaccinated Americans, according to the CDC. That may seem low, but it’s more than five times higher than the COVID-19 death rate for Americans who were fully vaccinated but had not received the new Omicron-targeting booster shot (0.35 per 100,000). It’s also more than 11 times higher than the COVID-19 death rate for Americans who had received the new bivalent booster shot (0.16 per 100,000).

If you’re looking for data close to home, consider these figures from Los Angeles County: Between Dec. 5 and Jan. 3, the COVID-19 mortality rate was 16.6 deaths per 100,000 unvaccinated residents, just under 5 deaths for every 100,000 residents who were vaccinated but hadn’t received the updated booster and 2.3 deaths per 100,000 residents who were both vaccinated and recently boosted.

One thing the relatives are right about is that the mortality advantage of the vaccines used to be bigger.

A study published last year by the CDC calculated that the risk of dying of COVID-19 was nearly 22 times higher for the unvaccinated than for the vaccinated in April and May of 2021, before the Delta variant arrived. In the Delta era, the COVID-19 mortality rate for the unvaccinated was 16 times higher than for the vaccinated. And at the height of last winter’s Omicron surge, COVID-19 was killing unvaccinated people at a rate 10 times higher than for vaccinated people, other CDC data show.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

The woman in the photo above is Amy McCoy, the owner of Forever Young Daycare in Mountlake Terrace, Wash. The infant she is communicating with (using baby sign language) was born in 2021, which makes her part of a noteworthy trend: The long, steady decline in the U.S. birthrate finally reversed in the second year of the pandemic, according to a report released today by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics.

A final tally of birth certificates concluded that the nation’s general fertility rate in 2021 was 56.3 births per 1,000 women of childbearing age (that is, between the ages of 15 and 44). That was a 1% increase over 2020, when there were 55.7 births per 1,000 women of childbearing age.

More importantly, it was the first such increase since 2014.

The total number of babies born in the U.S. in 2021 (3,664,292) was also 1% higher than it had been in 2020 (3,613,647). Before that, the number of births plunged 4% in the first pandemic year after dipping by an average of 1% between 2014 and 2019.

The CDC report doesn’t mention COVID-19, but every infant born in 2021 was conceived after the lockdowns began in March 2020. Perhaps when the data come in for 2022, statisticians will have a better idea of the pandemic’s role in reversing the country’s nearly decade-long baby bust.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.