Coronavirus Today: Will COVID-19 take a summer vacation?

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, June 14. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Since my kids returned to in-person classes in August, I’ve relied on their schools to keep me up to date on the state of the pandemic in our community.

When a student tested positive for a coronavirus infection, an email went out to the entire school. Those notifications became a lot more frequent after the Omicron variant arrived just after Thanksgiving; when classes resumed after winter break, they arrived in my inbox daily. The number of new cases reported in each dispatch rose as high as 11, in a high school with about 1,450 students.

Cases leveled off as the Omicron surge lost steam, then picked up again in April as the hyper-contagious BA.2.12.1 subvariant established itself here. Reports of multiple new infections were still coming in on a daily basis when the school year ended in the first week of June.

I miss those reports. I know the coronavirus is still circulating in my neighborhood, but I can’t tell whether cases are rising or falling.

The situation made me wonder whether the arrival of summer break would spark another COVID-19 wave or give the outbreak a chance to die down. So I pulled an editor move and assigned a reporter to find out.

Turns out, the experts are pondering this too.

“It’s very hard to accurately predict,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer told my colleague Corinne Purtill. “I’m less and less comfortable with the modeling and the predictions, and more and more comfortable with just noting that we have a lot of uncertainty.”

And here’s what USC virologist Paula Cannon had to say: “I’m a little cautious making predictions about the summer and COVID. If nothing else, I’ve learned this virus throws us curve balls all the time.”

On the one hand, with school out of session, kids won’t be gathering indoors for hours each day. If they meet up with their friends — either informally or through programs like camp or sports leagues — they’re likely to spend a good chunk of time outdoors.

On the other hand, people tend to let their guard down in the summer. Kids might get lazy about wearing masks and taking other precautions when they’re with their friends or in crowded places like amusement parks, graduation ceremonies, baseball stadiums or the beach.

Both of the last two pandemic summers saw small increases in coronavirus cases. In 2020, the bump came in July, with the country maxing out with a seven-day average of around 67,500 cases per day, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2021, the wave came a little later, peaking around 164,500 cases per day on Sept. 1.

It’s possible that 2022’s summer coronavirus wave is already on the downswing, even though summer won’t officially begin until next week. Nationwide, daily cases were averaging around 110,000 in late May, and have fallen a bit since.

“Will we have a wave this summer? Yes, we’re already soaking in it,” said Andrew Noymer, an epidemiologist and infectious-disease demographer at UC Irvine.

There is one thing we can say with certainty about summer break and COVID-19: In L.A. County, the official case count will drop dramatically starting this week.

That’s because the last day of school for L.A. Unified was Friday. When the district’s 600,000-plus students go on summer break, so does its weekly coronavirus testing program. During the school year, those tests accounted for roughly half of all results reported in the county, Ferrer said.

Without those tests to rely on, county officials will pay more attention to cases in hospitals, nursing homes, homeless shelters and other high-risk settings. Readings from wastewater treatment sites will also help fill the gap.

Here’s something else experts are sure of: The best way to impede the virus and protect yourself from its worst effects is to get vaccinated and boosted.

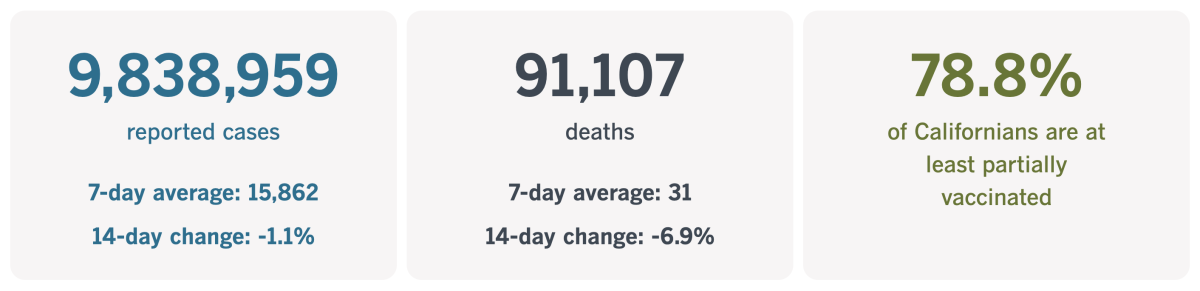

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 4:20 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Clearing the air in schools

While we’re on the topic of schools and COVID-19, let’s look at one of the pandemic’s potential silver linings — cleaner classroom air.

In the U.S., the typical K-12 school building is about 50 years old. That means there are tons of facilities with antiquated (if not broken) heating and air conditioning systems. They were prime candidates for upgrades long before the SARS-CoV-2 virus had begun circulating in the U.S. In June 2020, the Government Accountability Office estimated that 36,000 schools were due for new or upgraded HVAC systems.

What they needed to get them was money. That’s just what the pandemic provided: billions of dollars in federal aid that could be spent for this purpose.

A few months into the pandemic, scientists figured out that the coronavirus spreads easily through the air. In fact, making sure the air is clean is more important than wiping down door handles or installing plexiglass barriers around desks.

Schools had an infrastructure problem. Money was available to fix it. There was a public health emergency that made time of the essence.

And yet few schools have made major investments to improve their ventilation and filtration systems.

So says a report published last week by the CDC.

Researchers at the agency examined data from 420 schools across the country that participated in the National School COVID-19 Prevention Study. The schools answered survey questions between mid-February and late March.

Just 39% of schools said they had upgraded or replaced their HVAC systems in response to the pandemic. Even fewer installed high-efficiency particulate air filtration systems — 28% of schools said they added HEPA filters in classrooms, and 30% put them in dining areas.

Most schools opted for quicker (and cheaper) fixes. The most common was to simply move school activities outside, a practice adopted by 74% of surveyed schools. In addition, 67% of schools said they kept doors and windows open “when safe to do so,” according to the CDC report.

This being the pandemic, there were significant economic disparities.

While 45% of schools classified as “low-poverty” (due to the fact that no more than 25% of students were eligible for free or reduced-cost meals) upgraded or replaced their HVAC systems, only 32% of “mid-poverty” schools (those where 26% to 75% of students were eligible for free or reduced-cost meals) took the same steps. However, so did 49% of “high-poverty” schools (those where at least 76% of students could receive free or reduced-cost meals).

The pattern was similar for using HEPA filtration systems in places where students eat (and where they’re particularly vulnerable because they must remove their masks). The researchers reported that 37% of low-poverty schools took this precaution, along with 25% of mid-poverty and 35% of high-poverty schools.

The survey also asked about using portable HEPA filters in high-risk areas, such as isolation areas and the nurse’s office. Half of the low-poverty schools said they did, compared with 24% of mid-poverty and 45% of high-poverty schools.

The study also found that rural schools were less likely to make big-budget fixes than schools in cities, towns or suburbs.

For instance, 30% of rural schools either upgraded or replaced their HVAC systems. In other types of communities, that figure ranged from 39% to 43%. A little more than 19% of rural schools had HEPA filtration systems installed in places where students ate (compared with 27% to 33% of other schools) and 22% had portable HEPA systems in high-risk areas (compared with 34% to 45% elsewhere).

Better indoor air quality would do more than help keep COVID-19 at bay. It would reduce the risk of infectious diseases like influenza, reduce symptoms for those with respiratory diseases like asthma, and make life easier for those with allergies. Healthier students would miss fewer days of school, which may be why researchers have linked indoor air quality to math and reading skills.

The fact that so few schools have taken advantage of the pandemic funds must feel like a wasted opportunity to those who have been campaigning for cleaner air in schools.

“We haven’t had that amount of money coming from the federal government for school facilities for the last hundred years,” Anisa Heming, director of the Center for Green Schools at the U.S. Green Building Council, told Liz Szabo of Kaiser Health News.

But it might be that most school districts haven’t had time to focus on their HVAC systems. FutureEd, a think tank based at Georgetown University, analyzed district spending plans and found that they planned to invest nearly $10 million of pandemic relief funds on ventilation and filtration systems. That works out to about $400 per student.

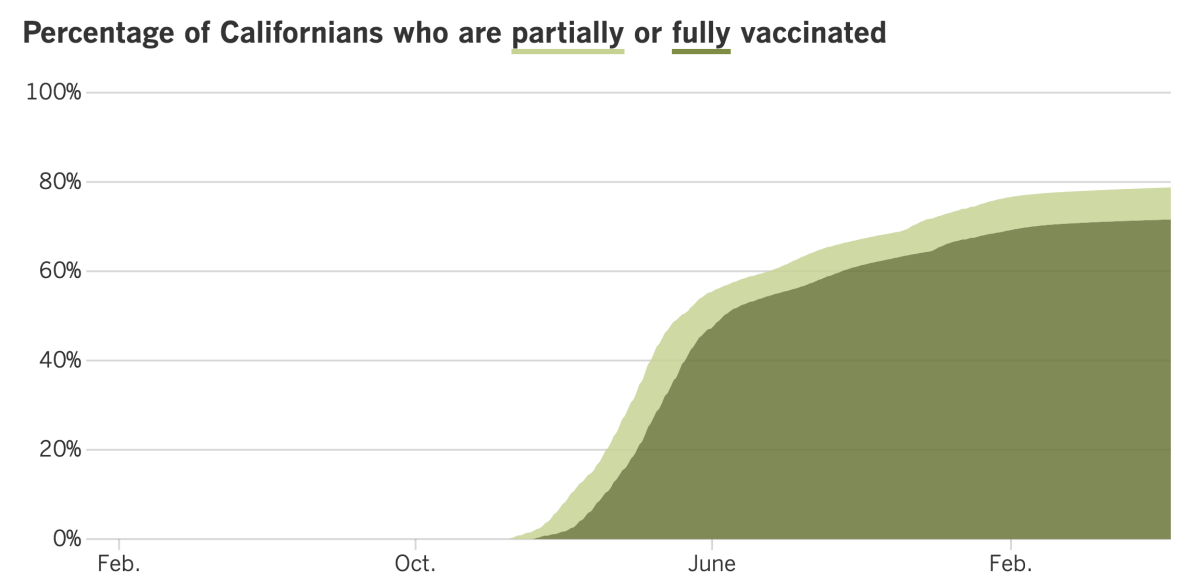

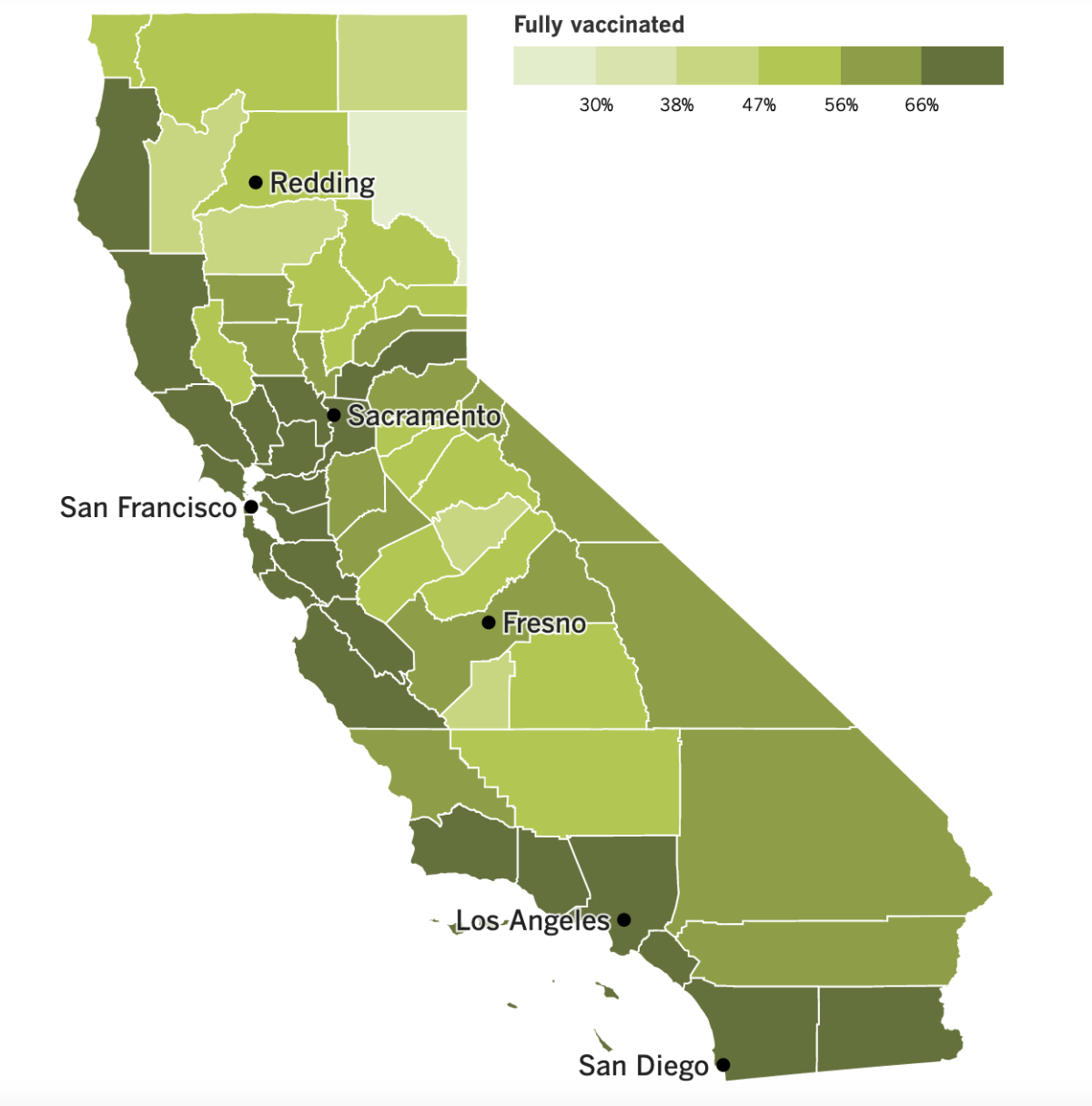

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

If you live in Los Angeles County and enjoy being maskless indoors, soak up that feeling now. If present trends continue, the county health department could issue a new indoor mask mandate in a matter of weeks.

The reason: L.A. County is on pace to achieve a high COVID-19 community level in early July.

So much for the recent cautious optimism that the BA.2.12.1-fueled wave may have peaked. Instead, the dip in new cases was probably just a lag in reporting due to the Memorial Day holiday. In fact, holiday gatherings may have served to accelerate coronavirus transmission, according to Ferrer.

In the week that ended Friday, the county averaged about 5,100 cases per day, up 20% from the week before. That works out to 350 new coronavirus cases per 100,000 residents per week, more than three times what’s needed to meet the CDC’s threshold for a “high” rate of transmission.

The number of hospitalized patients with coronavirus infections is also up 21% week-to-week.

Statewide trends are similar. California averaged 16,700 new infections per day during the week that ended Thursday, up 21% from the prior week. That amounted to 298 cases per 100,000 Californians per week.

Hospitalizations of coronavirus-positive patients throughout the state have increased roughly 26% in the last two weeks. Although many of those patients are being treated for something other than COVID-19, their infections have an outsize impact because extra safety procedures are required to keep the virus from spreading.

Perhaps some new vaccine options will help. Moderna said its experimental shot that’s designed to target the Omicron variant performed well in a preliminary study. People who got the shot — which also primes the immune system to fight the original coronavirus strain — saw an eightfold increase in antibodies capable of recognizing Omicron, the company said.

Other Moderna shots might be available as soon as next week. The Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine advisory committee unanimously endorsed versions of Moderna’s original vaccine for kids ages 6 to 17. The panel backed half-sized doses for 6- to 11-year-olds and a full-strength version for adolescents ages 12 to 17.

“The data do support that the benefits outweigh the risks for both of these doses, in both of these age groups,” said Dr. Melinda Wharton, a panel member from the CDC.

The main risk the advisors considered was a rare type of heart inflammation that’s mostly been seen in teen boys and young men. The side effect has also been seen with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, but Moderna’s shots got a closer look because they contained a higher dose.

A review of clinical trial data by FDA scientists found no confirmed cases of heart inflammation in children, but some panel members said it’s still something to watch out for because the studies might have been too small for a case to crop up. Other side effects were things like sore arms, headaches and fatigue.

If the FDA follows the panel’s advice and authorizes the vaccine, the next stop is for the CDC to decide whether to recommend it.

Next up for the advisory committee: an analysis of shots for infants, toddlers and preschoolers. The panel will meet Wednesday to evaluate Pfizer’s low-dose, three-shot vaccine regimen for children ages 6 months to 4 years and Moderna’s low-dose, two-shot option for youngsters 6 months to 5 years.

An FDA analysis of clinical trial data determined the Pfizer regimen was 80% effective at preventing infections that cause COVID-19 symptoms. Moderna’s series was about 40% to 50% effective at preventing milder infections. A direct comparison isn’t possible because the two shots were tested at different times and faced a different mix of coronavirus variants. Both vaccines were deemed safe.

The nation’s 18 million children under 5 are the only ones who are still waiting for a COVID-19 vaccine option, but if either vaccine is cleared by the FDA and CDC, that could change as soon as next week. Pharmacies are already placing orders for the millions of doses made available by the Biden administration in anticipation of federal authorization.

On the research front, a new study found that babies exposed to the coronavirus in utero were more likely to be diagnosed with a brain development disorder in their first year of life than babies whose mothers were infection-free throughout their pregnancies.

The study included 7,772 babies born in the early months of the pandemic. Researchers checked their medical records for codes associated with disorders related to things like motor function, speech or language. The odds were small for both groups — 6.3% for those exposed in utero and 3% for those who weren’t. After accounting for other risk factors, researchers found that a mother’s SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with an 86% increased risk of a diagnosis.

“This should be another wake-up call for pregnant women to get vaccinated, and boosted, and stay masked and take as many precautions as they can,” said Dr. Kristina Adams Waldorf, an obstetrician-gynecologist who studies infectious diseases in pregnancy and wasn’t involved in the study.

The past week brought good news for travelers: The Biden administration no longer requires international airline passengers to test negative for a coronavirus infection in the 24 hours before boarding a flight. The rule went into effect in November as the Omicron variant swept across the globe and expired Saturday night. Adult visitors with non-U.S. passports still need to show proof of vaccination, with limited exceptions.

And as of Friday, Japan began accepting visa applications for foreign tourists, though they must be willing to book a guided package tour, wear masks and follow other anti-COVID measures. Tourists who follow these rules will arrive no sooner than late June.

While we’re in Asia, a group of experts appointed by the World Health Organization to investigate the pandemic’s origins says further research is needed to determine how the global outbreak began. “Key pieces of data” are still missing, they said, and they “remain open to any and all scientific evidence that becomes available in the future to allow for comprehensive testing of all reasonable hypotheses.”

There’s plenty left to investigate, including the wild animals that might have been the initial hosts of SARS-CoV-2 and the places where the virus might have first spread, like the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, they said.

Notably, the experts called for a more detailed look into the possibility that it all started with a laboratory accident since such mishaps have triggered outbreaks in the past. That was a sharp reversal from the WHO’s initial assessment last year that it was “extremely unlikely” COVID-19 might have spilled into humans from a lab.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: How can I tell if my kid’s summer camp is taking COVID-19 seriously?

The CDC’s guidelines for camps are the same as for K-12 schools and child-care centers. Regardless of the COVID-19 Community Level where the camp is located, it should:

- Promote vaccination and encourage everyone — campers and staffers — to get up to date with their shots, including booster doses.

- Make sure people stay home when they are sick. Offering paid sick leave will encourage workers to remain home if they are not well so they don’t risk infecting others.

- Check that indoor areas have good ventilation.

- Encourage everyone to wash their hands before and after eating and provide plenty of soap and/or hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol.

- Clean surfaces at least once a day. If someone tests positive for a coronavirus infection within 24 hours of being at camp, the facility should be cleaned and disinfected.

- Support those who wish to wear masks.

In addition, camps that draw people from a wide area should consider asking campers and staffers to take a coronavirus test shortly before they arrive. If the camp is in a place with a medium or high COVID-19 Community Level, a program to provide screening tests should be considered.

Make sure the camp has a plan to deal with a COVID-19 outbreak, just in case. The plan should include a way to isolate those who test positive and others who have COVID-19 symptoms. If the camp already has a coronavirus screening program, tests can be given more frequently. A universal mask mandate may be considered until the outbreak ends.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

Considering that the Dodgers have won just four games this month, you might suspect that the photo above wasn’t taken recently. You’d be right — it’s from June 15, 2021.

That date — a year ago tomorrow — was significant because it was the day California fully reopened its economy. After 15 months of stay-at-home orders, color-coded risk tiers and universal mask mandates, life seemed like it had returned to normal.

Dodgers fan Alice Maldonado, above, was able to cheer on her team in a stadium that no longer had capacity limits. As you can see, she was thrilled to do so (or maybe she was overjoyed to snag a Justin Turner bobblehead doll before supplies ran out).

Gov. Gavin Newsom was in a celebratory mood at Universal Studios Hollywood, where 10 vaccinated Californians won $1.5 million each in the state’s Vax for the Win sweepstakes. But he was also cautious.

“This is not a day where we announce ‘mission accomplished,’” he said. “Quite the contrary.”

His remark was prescient. Up until that point, California had recorded 3,778,123 coronavirus infections and 62,910 COVID-19 deaths. In the year since, the state has experienced an additional 6,060,836 infections and 28,197 deaths.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.