Coronavirus Today: Who deserves COVID-19 medicines?

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and I’m getting an assist today from newsletter veteran Deborah Netburn. It’s Friday, Feb. 4. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Remember when COVID-19 vaccines were new and in high demand? When the big question wasn’t how to convince people to get them but how to ensure they weren’t all snapped up by those at the high end of the socioeconomic spectrum?

It’s time to have that conversation again, except this time it’s about COVID-19 treatments.

The sought-after drugs are for people who are newly infected and face a high risk of becoming severely ill or dying. They include the antiviral medications Paxlovid and molnupiravir, as well as the monoclonal antibody therapy sotrovimab, the only one that’s effective against the Omicron variant.

In the first four weeks of January, the federal government disbursed enough Paxlovid and molnupiravir to treat nearly 1 million patients, along with roughly 200,000 courses of sotrovimab. Those amounts were woefully inadequate considering that more than 20.5 million new coronavirus infections were reported last month.

Also in high demand is Evusheld, an antibody infusion that could bolster the immune systems of the 10 million to 17 million Americans who can’t muster strong reactions to COVID-19 vaccines or can’t take them at all. Yet fewer than 300,000 doses have been sent to hospitals.

“It’s not even scratching the surface” of the need right now, JP Lieder, a University of Minnesota ethicist, told my colleague Melissa Healy.

Pandemic history suggests that the limited supplies are probably going to people who are whiter, richer and healthier than those being passed over.

For the most part, the medications are being sent to states, which can dole them out however they see fit, Lieder said. And in many cases, they’re being made available to the patients who call dibs.

In a first-come, first-served system, the people who get to the front of the line — heck, who even realize there’s something to line up for — tend to be more affluent, better-insured and more highly educated. Behind them will be the poor and more socially vulnerable.

Unfortunately, these are the people who are most likely to become severely ill or die if they catch COVID-19. Americans in the bottom third of the socioeconomic spectrum have been 48% more likely to die of the disease than those in the top third. And people of color are overrepresented in that bottom third.

“The wealthy and well-connected will win the race,” said Dr. Douglas B. White, a bioethicist and critical care doctor at the University of Pittsburgh. It’s “the poster child for an unfair system.”

A report last month by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID-19 Response Team bears this out. The team found that over a 10-month period that ended in August, Latinos who tested positive for coronavirus infections were 58% less likely than similar non-Latino Americans to be treated with monoclonal antibodies. In addition, newly infected Black people were 22% less likely than their white counterparts to get the treatment.

Mindful of this, some states and counties are trying to take the race and ethnicity of patients into account when they decide how to mete out the limited medical supplies. They hope they don’t make existing disparities worse.

Minnesota, for instance, has employed a lottery system for allocating the drugs that takes into account a broad measure of patients’ socioeconomic status. Pennsylvania has a lottery, too; White helped develop it.

For the record:

9:25 p.m. Feb. 8, 2022An earlier version of this newsletter said California developed the Healthy Places Index to help it distribute COVID-19 vaccines fairly. That index was developed by the Public Health Alliance of Southern California, and state officials used it to create their own health equity metric.

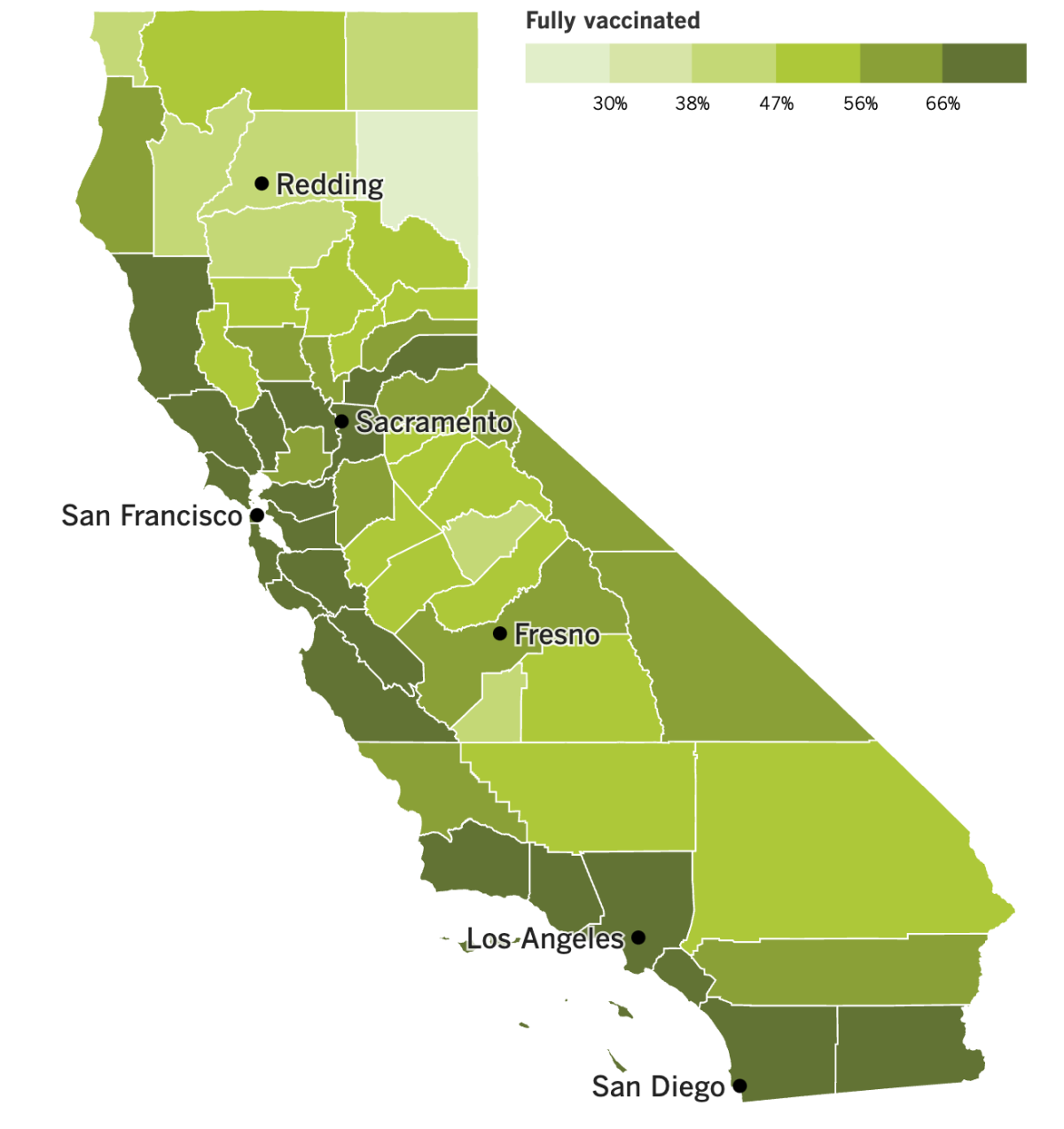

California is using its own broad measure of a community’s socioeconomic well-being, which it adapted from a measure called the Healthy Places Index, to guide the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines. The state’s health equity metric makes no reference to race or ethnicity and instead focuses on factors including housing density, poverty, education levels and access to supermarkets and healthcare.

Some of the systems designed with fairness in mind have sparked a backlash. New York City, for instance, came up with guidelines for healthcare systems that included race and ethnicity, among other risk factors. That system faces a legal challenge.

Former President Trump has been stoking the reverse-racism sentiment. In New York, he charged, “if you’re white, you have to go to the back of the line to get medical health.”

By the numbers

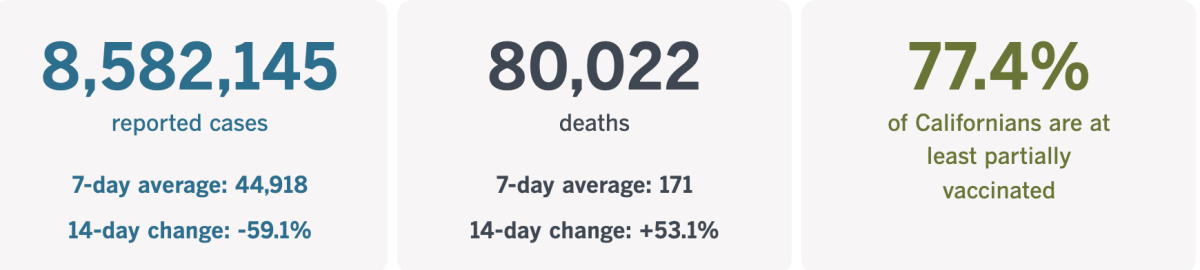

California cases and deaths as of 6:15 p.m. Friday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Can China pull off a zero-COVID Olympics?

The Tokyo Olympics were the COVID Olympics. The Chinese government is hoping to make the Winter Games in Beijing something different: the “zero-COVID” Olympics.

That seemed doable in the waning days of the Delta wave. Then along came Omicron, and dodging the coronavirus became something of an Olympic event itself.

Every day, the 3,000 or so athletes in Beijing must follow a regimen of throat swabs, face masks and frequent temperature checks, my colleague David Wharton reports. Those who leave the Olympic fortress known as the “closed loop” could find themselves sent home.

“The prevention and control work of Beijing 2022 has been rigorous and scientific,” said Huang Chun, a health official with the local organizing committee. “We will ensure there is no room for error.”

The prevention efforts begin before athletes depart for China. They’re supposed to get vaccinated first (Swiss snowboarder Patrizia Kummer opted to come to China early and quarantine for three weeks instead), then they have to pass a pre-travel coronavirus test.

U.S. hockey player Amanda Kessel said she couldn’t sleep after her preflight test. “You never feel safe until you get that negative back,” she said.

She got the result she was hoping for, but bobsledder Josh Williamson didn’t. He is stuck stateside and hopes to join his team before the men’s bobsled competition begins Feb. 14.

“This has not been an easy pill to swallow,” Williamson said in an Instagram post. “I have felt pretty helpless.”

Those in the clear must fly into China on specially designated flights. Once the athletes land, they’re greeted by legions of healthcare workers covered head to toe in white protective suits. (Wharton says they resemble the storm troopers of “Star Wars.”)

Coronavirus tests continue daily once athletes are inside the closed loop, which is cordoned off from the rest of Beijing by high fences, security guards and surveillance cameras. All those tests mean there’s a constant risk of having your Olympic dream crushed by a microscopic foe.

U.S. skier Mikaela Shiffrin got a scare when she tested positive a few days after Christmas. She had to skip some World Cup races in Austria, but she recovered in time for the Olympics. Those who test positive from here on out may not be as lucky.

“It has definitely been stressful,” said speed skater Brittany Bowe, who intends to compete in her third Olympics. “You’re usually worried about being in perfect shape, but this year has added a whole new element of trying to stay healthy.”

As of Friday, the number of coronavirus cases at the Games had reached 308. That tally may seem high, but Dr. Mike Ryan, the World Health Organization’s emergencies chief, said he was confident visitors would be safe.

“The measures that are in place for the Games are very strict and very strong, and we don’t at this point see any increased risk of disease transmission in that context,” he said.

Indeed, the measures might have been too strong. Officials agreed to reduce the sensitivity of their coronavirus tests to address concerns that athletes who had fully recovered from an infection could still test positive if harmless fragments of viral RNA remained in their bodies. They also shortened the quarantine period to seven days.

Unlike in Tokyo, Beijing will allow limited groups of spectators over the 17 days of competition.

Gracenote, a sports analysis and data company, projects the U.S. will win 22 medals. That would put the American team fourth behind Norway (44), Germany (30) and the Russian Olympic Committee (30). But the company has less confidence in its predictions than usual, my colleague Nathan Fenno reports.

“The problem is that we do not know who may or may not be out of competition due to a positive COVID test,” said Gracenote’s head of sports analysis.

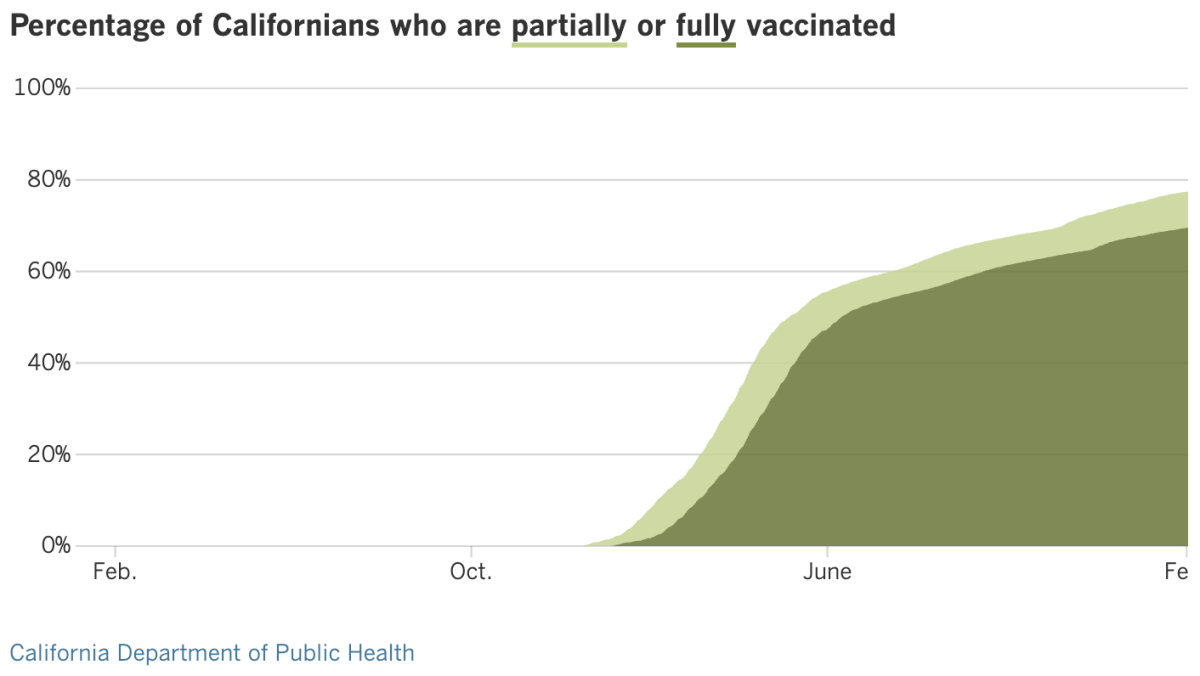

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

As the parent of two kids in the L.A. Unified School District, I’m thrilled to report that coronavirus infections have declined about 70% in L.A. County schools since the start of the spring semester, according to figures released Thursday by Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer.

Of the 486,000 tests administered to students last week, just 4% came back positive, compared with 14% in early January.

The numbers represent a significant step in the right direction, but positivity rates are still much higher than before the Omicron surge. In the last week of school before winter break — when Omicron started to push up numbers — the student infection rate was 0.22%.

The decline in infections aligns with other data suggesting that the winter peak has passed. But Ferrer said students and school staffers will be required to wear masks indoors and outdoors until there is further significant improvement in health metrics, which will affect not just school policy but also whether face coverings will be required in other outdoor settings.

Specifically, officials said Thursday that face coverings would no longer be required at outdoor “mega” events with at least 5,000 attendees (such as those at the Hollywood Bowl, Dodger Stadium or SoFi Stadium) when coronavirus-positive hospitalizations drop below 2,500 for seven straight days. As of Wednesday, just under 3,400 coronavirus-positive patients were hospitalized countywide.

It’s unlikely L.A. County will reach that goal in time for the Feb. 13 Super Bowl, but it could come relatively soon after, Ferrer said.

Masks will still be required at indoor establishments and events. Those won’t lift until the county drops below 50 new coronavirus cases per 100,000 people over a weeklong period and the positive test rate is less than 8%.

Although the positivity rate had fallen below 8% on Wednesday, L.A. County is averaging about 1,100 new coronavirus cases per 100,000 people.

All of California is currently under a mask order that applies to indoor public spaces. That mandate is set to expire Feb. 15, and it remains to be seen whether it will be extended. If the state does allow the mask order to expire, counties with no local mask order — including Orange, San Diego, Riverside and San Bernardino — would be on track to see their mask rules lifted.

Desperate as we might be to believe this pandemic might be over, California and the nation both marked sobering milestones Friday. More than 80,000 Californians have lost their lives to COVID-19 — roughly equivalent to the population of Lakewood or Tustin — while deaths across the United States surpassed 900,000, according to Johns Hopkins University. Experts expect that the U.S. death toll will eventually exceed 1 million.

In the meantime, some hospitals in the United States are hoping to turn to foreign nurses as a solution to severe shortages brought on in part by the pandemic. It turns out there’s an unusually high number of green cards available this year for foreign professionals, including nurses, who want to move to the United States — twice as many as just a few years ago.

That’s because U.S. consulates that shut down during the pandemic weren’t issuing visas to relatives of American citizens, and, by law, these unused slots are now available to eligible workers.

The U.S. typically offers at least 140,000 green cards each year to people moving to the country permanently for certain professional jobs, including nursing. Most are issued to people who are already living in the United States on temporary visas, though some go to workers overseas.

This year, 280,000 green cards are available, and recruiters hope some of the extras can be snapped up by nurses seeking to work in pandemic-weary hospitals in the United States.

And, finally, some updates from across the globe.

South Korea continues to experience record-breaking coronavirus cases in the wake of the Lunar New Year holiday. The country reported 27,443 new cases Friday, 4,500 more than the previous one-day record, set Thursday. In response, government officials will restrict private social gatherings of those who are fully vaccinated to six people, while requiring unvaccinated people at restaurants to eat or drink alone. Public indoor dining is banned after 9 p.m., and proof of vaccination or a recent negative test is required to enter nightclubs, karaoke rooms and gyms.

In Europe, leaders are moving in the opposite direction.

On Thursday, Sweden joined other European nations in saying it would remove coronavirus restrictions. Starting Wednesday, the country will allow a to return to restaurants with no limit on how many people can be there, how much space there should be or opening hours. Requirements for vaccine certificates and masks on public transportation will be dropped, as will the recommendation to limit social contacts.

Denmark took the lead among European Union members by scrapping most restrictions Tuesday. Hours later, Norway lifted its ban on serving alcohol after 11 p.m. and a cap on private gatherings of no more than 10 people.

The reason for Sweden’s move is similar to that of Denmark: Although there is an increase in infection rates, it is not burdening hospitals, and high vaccination rates are making the situation look more hopeful.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: How soon might a COVID-19 vaccine be ready for preschoolers?

Perhaps a few months sooner than if the Food and Drug Administration hadn’t nudged Pfizer and BioNTech to go ahead and submit their application for their vaccine aimed at those under 5, but there are still a lot of steps to go. In the best-case scenario, the first doses could be available to infants by March.

Here’s a quick look at each of those steps:

- FDA scientists will review Pfizer’s application for emergency-use authorization for its shots, which contain one-10th the dose of the adult version of the vaccine. They’ll focus on data collected during clinical trials of children ages 6 months to 4 years.

- The FDA will also hear from its committee of independent advisors on vaccines. They’re scheduled to discuss the new formulation at a meeting Feb. 15.

- After all the science is in, the FDA will decide whether to authorize the new shots. They were tested as a two-dose primary series, which seemed to work fine for babies but wasn’t that strong in 2- to 4-year-olds. A trial of a three-shot series is underway, with results expected in late March. It’s possible the FDA could authorize the first two doses to get the ball rolling, then authorize a third dose for preschoolers later.

- If the FDA signs off, the CDC will convene its own vaccine advisory committee to debate whether the vaccine should be recommended for use. It’s possible for them to endorse them for all children in the target age group, or for only some of them.

- After the advisory committee makes its recommendations, the CDC director will make her decision. She usually follows the committee’s advice, but she’s not required to.

- If the vaccine wins the CDC’s backing, the final step for California is an independent assessment by the state’s Scientific Safety Review Workgroup. Oregon, Washington and Nevada also have representation in the group, which typically acts within a day of the CDC’s sign-off.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

This trash can contains the detritus of a COVID-19 booster shot clinic at a nursing home in Spain. Multiply it by a gazillion and you’ve got an 87,000-ton problem.

A report out this week from the World Health Organization looks at the volume of medical waste generated by the pandemic.

Used gloves are the trashiest item, generating more than six times as much waste as discarded face masks, the report says. The COVID-19 test kits distributed as of November will generate nearly 200,000 gallons of chemical waste — enough to fill one-third of an Olympic-size swimming pool.

About 44% of pandemic-related medical waste is made up of what the WHO report describes as “nonessential PPE,” including surgical caps and shoe covers. Governments, the medical community and the public at large should be more conscious of the products they’re using — and overusing — to minimize the trash problem, the report says.

“It is absolutely vital to provide health workers with the right PPE,” Dr. Michael Ryan, the WHO’s emergencies chief, said in a statement. “But it is also vital to ensure that it can be used safely without impacting on the surrounding environment.”

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.