Coronavirus Today: How past pandemics came to an end

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Jan. 4. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Happy New Year! Did you make any resolutions? I’ve got one that’s sure to be popular: Bring this pandemic to an end in 2022.

If only it were up to me.

All kidding aside, it’s entirely possible that COVID-19 won’t be a global public health emergency by the time the year is over. All previous pandemics and epidemics have come to an end, and this one will too. So let’s kick off 2022 on a positive note by looking back at how life returned to normal in the past.

The 1918 flu

As my colleague Jessica Roy explains, we didn’t so much beat this flu as survive it. The disease — which you may know as the Spanish flu, though health officials frown at naming diseases after people, places or animals — killed an estimated 675,000 Americans at a time when the population was one-third the size it is now. About 2.5% of U.S. residents who caught the flu died, and the case-fatality rate around the world was as high as 10% to 20%. After about one-third of the global population became infected and roughly 50 million people died, the virus ran out of steam. Those who survived had immunity, and the virus gained mutations that made it less virulent. Descendants of the pandemic strain are still with us today.

Polio

More than 600,000 people in the U.S. contracted this highly contagious disease in the 1900s, and nearly 10% of those who caught it died. Children were its primary victims, and many who survived were left paralyzed or confined to iron lungs. Schools were closed to keep the disease from spreading. But what stopped the outbreak was the vaccine invented by Jonas Salk. The technology was still new, and a small number were sickened by the vaccine. One tainted batch that contained live virus killed a handful of people. Even so, the vaccine was widely embraced by people who were terrified of the disease. “You would have had to have been a psychopathic monster to not want to be part of the solution,” said Paula Cannon, a virology professor at the USC Keck School of Medicine. Polio was eradicated in the U.S. by 1979.

Smallpox

This disease dates back to at least 1157 BCE, and European colonizers brought it to North America in the early 1500s. The virus responsible for the majority of cases had a fatality rate of around 30%. Before there was a vaccine, some people tried to head off smallpox’s worst effects by deliberately infecting people with a weakened version so they could develop immunity. (An enslaved man named Onesimus who was inoculated in West Africa is credited with introducing the idea to North America in 1721.) Edward Jenner developed a smallpox vaccine in England in 1796, and vaccines ultimately spread around the globe. In 1980, the World Health Organization declared smallpox eradicated — the only infectious disease to be conquered by humanity.

HIV/AIDS

In the early years of the epidemic, roughly half of Americans who became infected with HIV died of AIDS or a related condition within two years. Deaths peaked in 1995 at about 50,000, then decreased steadily thanks to two things: effective prevention measures and new medications that are capable of knocking back the virus to undetectable levels. Work continues on an HIV vaccine.

SARS

Our response to severe acute respiratory syndrome had a lot of things going for it that were missing with COVID-19: A test was developed quickly to identify people with the disease. There weren’t any asymptomatic infected people who become silent spreaders. The public health system was in better shape and swung into action right away. Through coordinated action, the disease that originated in China was confined to just 28 countries. A total of 8,098 people became infected worldwide during the 2002-2003 outbreak, and 774 died. SARS stopped spreading before scientists had a chance to create treatments or vaccines.

H1N1 flu

Like the 1918 flu, this pandemic in 2009 was caused by an H1N1 influenza. It’s often known as swine flu because it emerged in pigs before jumping to humans, who had no natural immunity to this brand-new strain. Hundreds of millions of people — and perhaps more than 1 billion — became infected, though the fatality rate was estimated to be about 0.02% during the outbreak’s first year. Existing medicines, including Tamiflu, were still largely effective, and it took about six months to ready a vaccine targeted to the new strain. The pandemic was declared over in August 2010, but versions of the flu are still among us.

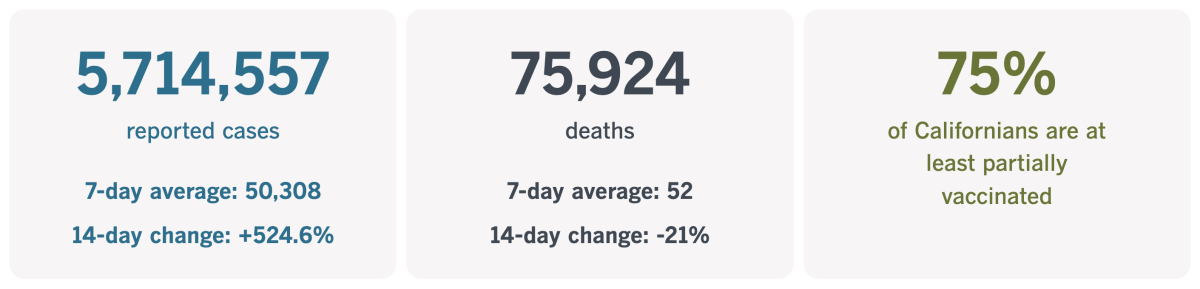

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 4:15 p.m. Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

How the pandemic has fueled an ‘invisible addiction’

As we’re often reminded, the pandemic has made other problems worse. Here’s one example you may not have been aware of: gambling.

Putting money on the line in a game of chance can be exhilarating. And thanks to the brain chemical dopamine, the feeling that accompanies a win can be addicting.

That’s become the case for about 2 million Americans who struggle with problem gambling. Their ranks have grown since the coronavirus arrived in the U.S. nearly two years ago, my colleague Kurtis Lee reports.

Gambling can distract us from the fear of catching a life-threatening disease, the anxiety brought on by economic uncertainty, the boredom of social isolation, and the stress of having to cope with so many unfamiliar situations. For those who recognize they have a problem, doing something about it is more challenging because of the pandemic.

“A lot of people have been alone and struggling with their addiction,” said Lou Remillard, a Las Vegas restaurateur who racked up tens of thousands of dollars worth of debt betting on sporting events and playing blackjack.

Remillard placed his last bet in 2018. Now he facilitates Zoom meetings for people in recovery.

“All we can do is help each other,” he said.

There are lots of signs that problem gambling has become more common in the COVID-19 era:

• Calls to a helpline run by the National Council on Problem Gambling in Washington, D.C., increased from around 16,600 a month in 2019 to about 21,700 a month in 2021. Helplines in about a dozen states have become busier as well, especially fielding calls from people in their 20s, 30s and 40s.

• A survey of 2,000 people conducted by the national nonprofit revealed the risk of problem gambling had doubled since 2018.

• A program in Massachusetts that allows people to ban themselves from the gambling floors of casinos in the state has more enrollees now — about 1,000 — than it ever has before.

• In 2019, commercial casinos across the U.S. took in a record-setting $43.65 billion. In 2021, they exceeded that amount by at least $500 million, according to the American Gaming Assn.

• Americans bet $3.16 billion on sports in the first 10 months of the year — more than double the amount in the first 10 months of 2020, the gaming group says.

Not all gambling is problem gambling. But among those who are addicted or have a gambling disorder, only 10% seek treatment, according to the American Psychiatric Assn.

Bea Aikens has been in recovery for an addiction to video poker for 25 years. She counsels others who struggle with problem gambling and tries to get them to see they have a disease, not a moral weakness. The number of people reaching out for help has increased since the first coronavirus lockdowns of March 2020, she said.

“It’s really an invisible addiction,” she said. “We have to get the word out and let people know they’re not alone.”

That’s what Remillard is trying to do with his daily Zoom meetings.

“What matters is that we keep showing up,” he said. “I keep showing up, that’s all we can do.”

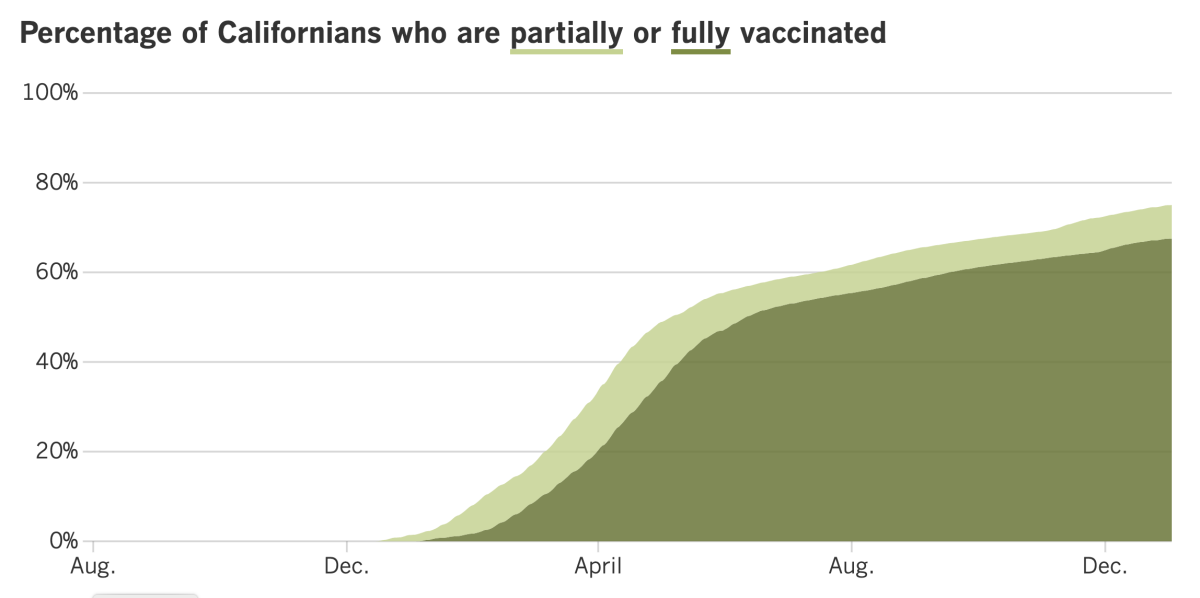

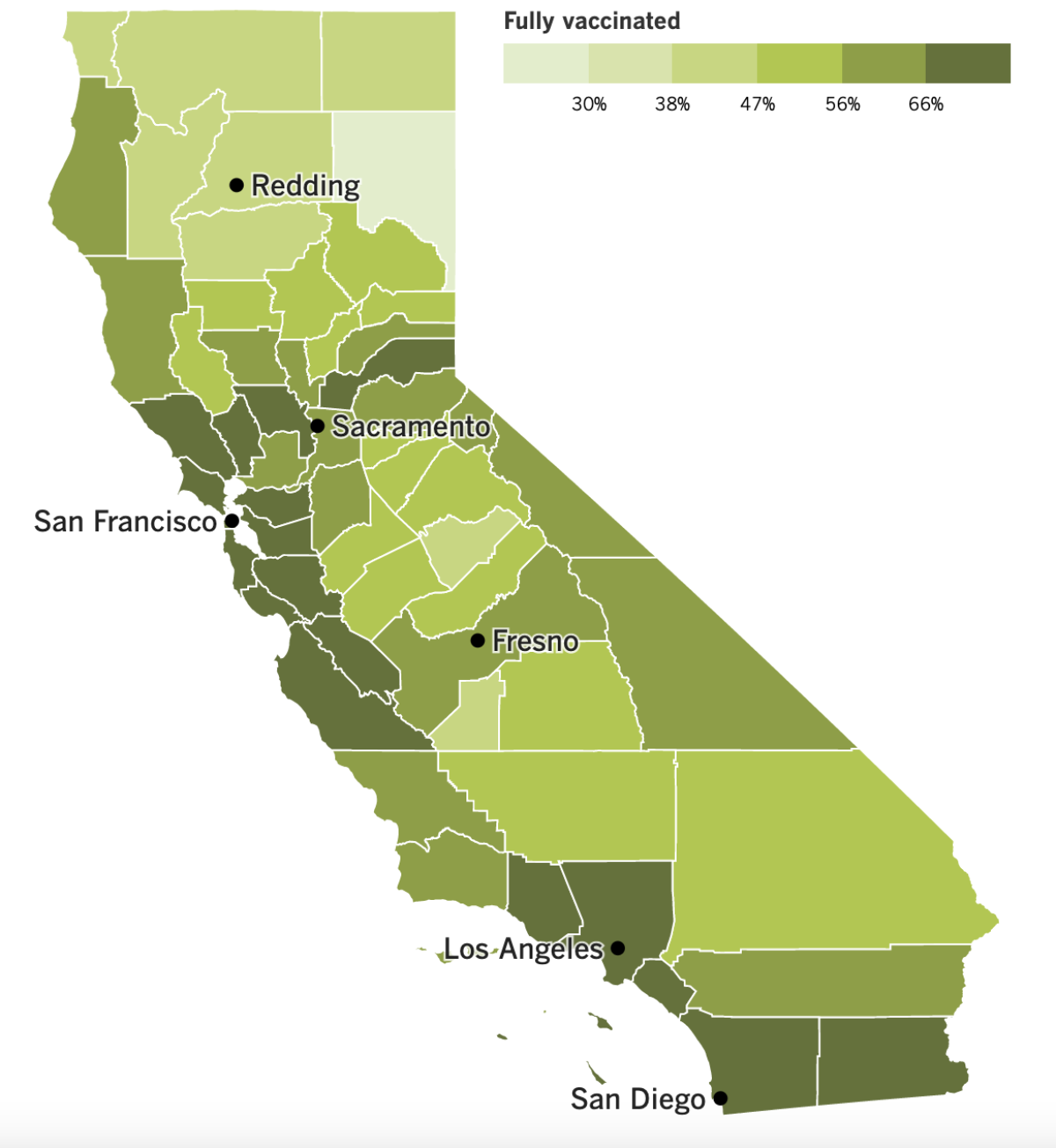

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

They told us so.

After weeks of holiday celebrations, the number of Southern Californians with coronavirus infections has spiked since Christmas, with case counts more than doubling in the last nine days in Los Angeles, Orange and Ventura counties. What’s more, the number of infected patients hospitalized in L.A. and San Bernardino counties is now higher than it was at the peak of last summer’s Delta surge.

Hospitals are still in much better shape than they were this time last year, before vaccines became widely available. Back then, most hospitalized patients who had coronavirus infections were admitted because they had COVID-19. Now, about two-thirds of them were admitted for something unrelated to the virus, said Dr. Christina Ghaly, director of the L.A. County Department of Health Services.

If present trends continue, Southern California may avoid some of the worst-case hospitalization scenarios envisioned weeks ago. But we’re certainly not out of the woods.

In L.A. County, crowded hospitals are forcing ambulances to wait to offload patients, causing delays in 911 call response times. An increase in employees who are forced to stay home with COVID-19 symptoms is another contributing factor, since being short on staff makes everything take longer.

And in San Diego County, more than 80% of emergency rooms are on diversion status, meaning they’re so busy with patients already in their waiting rooms that they’ve cut back their incoming ambulance traffic. Usually when that happens ambulances are rerouted to other hospitals; now, there’s nowhere else to send them.

In L.A. County at least, the surge in cases is being driven by adults under age 50. Coronavirus case rates among residents ages 18 to 29 are more than eight times higher now than they were a month ago. For adults in their 30s and 40s, case rates are six times higher.

Altogether, adults under 50 accounted for more than 70% of confirmed infections between Dec. 22 and 28. A year earlier, they made up 55% of cases.

In Orange County, adults under 45 are driving coronavirus transmission, said Dr. Regina Chinsio-Kwong, a deputy health officer.

In a sign of just how fast cases are rising, federal jury trials have been put on hold for three weeks in Los Angeles, Santa Ana and Riverside. A panel of eight judges ordered the pause on Monday, and Clerk Kiry K. Gray explained in a statement that jury trials “would place court personnel, attorneys, parties and prospective jurors at undue risk.”

California officials are hoping to contain the virus’ spread with new recommendations for infected people in isolation that are more strict than the controversial ones put out last week by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As you may recall, the CDC shortened the period of time infected Americans were advised to stay home from 10 days to five. After that, if they have no symptoms, they can return to normal activities as long as they wear a mask everywhere they go — and even around other people at home — for at least five more days. (Guidance for people in quarantine after being exposed to an infected person was similarly loosened.)

California officials now say that infected people can exit isolation after five days only if they take a new coronavirus test and it comes back negative.

Dr. Robert Wachter, chair of the UC San Francisco Department of Medicine, praised California’s stricter guidelines. “Kudos,” Wachter said in a tweet. “Safer than [CDC’s] version.”

For its part, the CDC doubled down on its new recommendations Tuesday by laying out the scientific basis for them. The agency said more than 100 studies from 17 countries had shown that people were most infectious soon after infection — two days before and three days after symptoms (if any) appear. Although those studies predate Omicron, early data from the U.S. and South Korea suggest the course of an Omicron infection moves more quickly than with earlier variants, the CDC said.

As for the lack of testing after Day 5, the CDC said a negative result with an at-home test might not necessarily mean there’s no threat. On the flip side, a positive result from a laboratory test doesn’t necessarily indicate a person is still contagious.

Besides, getting tested isn’t as easy as it ought to be. At-home testing kits are still hard to find, and community testing sites are overwhelmed.

Bertha Carrillo went to a Kaiser drive-through testing site in Anaheim on Sunday that was scheduled to open at 9 a.m. Even though she arrived at 6:30 a.m., there were already eight cars ahead of her.

Another testing site at the Kaiser Permanente Downey Medical Center was packed with so many cars on Tuesday that police had to shut it down.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Are any of California’s new laws aimed at protecting people from COVID-19?

Yes.

A law known as Senate Bill 606 will make it easier for workplace safety inspectors to issue blanket citations to companies with a pattern of violations without needing to visit each site individually. That’s important because the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health says it has enough staff to visit only 20% of sites with complaints lodged against them.

Under the new law, Cal/OSHA must issue larger fines against companies whose workers are killed or hospitalized due to “willful” safety violations. The idea was to get away from the lighter penalties the agency long preferred — and that failed to deter employers from flouting safety rules, critics said.

“You had large employers just ignoring the public health guidance on social distancing, masking and other measures,” Eduardo Martinez, legislative director of the California Labor Federation, told my colleague Margot Roosevelt. “As a result, a lot of workers got sick and many of them died.”

The new law was motivated by the pandemic, but it applies to all workplace safety situations.

Another new law, Senate Bill 510, aims to prevent cases of COVID-19 by requiring health insurance companies to offer free coronavirus tests to their customers. The law also guarantees access to tests and vaccinations even when people go to a provider who is not in their insurer’s network.

In theory, coronavirus tests were already free, but some patients were still hit with out-of-pocket fees and other surprise bills that were a headache to deal with. The idea behind the new law is to make the “free” part clear to everyone so patients won’t be discouraged from seeking a test or vaccine, said Sen. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), the bill’s author.

“This is about public health,” Pan told my colleague Melody Gutierrez when Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the bill in October. “We don’t want to be flying blind as a society. When people think they might be infected, we want them to get tested during a pandemic. We need to minimize barriers.”

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.