Coronavirus Today: Are we there yet?

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Friday, Oct. 15. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

If the pandemic were a road trip, this would be the time for kids in the backseat to start asking, “Are we there yet?”

There’s good reason to think we might be getting close, at least in California.

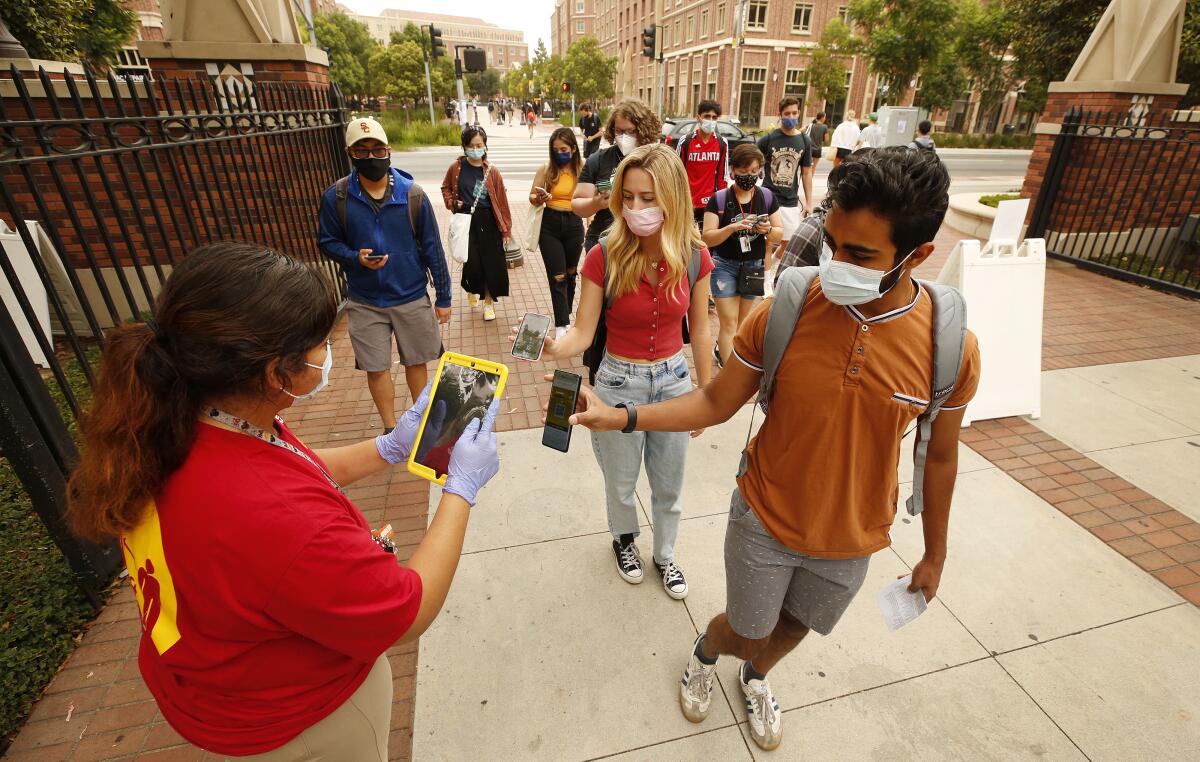

The Delta surge is on the downswing. Schools have been operating safely at pretty much full capacity. The Golden State continues to post the lowest rate of COVID-19 community transmission — 54.7 cases per 100,000 people over the last seven days — of any state in the country. More than two-thirds of all Californians are at least partially vaccinated, and that figure continues to rise.

Heck, Dr. Anthony Fauci even gave us permission to resume trick-or-treating this Halloween.

All of those accomplishments are worth celebrating. But, unfortunately, we still have quite a ways to go before we’re really out of the woods.

“We seem to have turned a corner in our fight against COVID,” said Dr. Robert Wachter, chair of UC San Francisco’s Department of Medicine. “But we’ve turned corners before only to run into oncoming trains.”

We’re likely to encounter more oncoming trains as fall turns to winter. The coronavirus spreads more readily in drier, colder weather. And since that kind of weather forces people to spend more time indoors, the virus could get an additional boost.

Last year’s mild flu season might make us more vulnerable this time around, increasing the potential for a “twindemic.”

There’s also the risk that the Delta variant will be replaced by something even worse. With so much of the world still unvaccinated, there’s plenty of opportunity for the virus to evolve into a more dangerous strain.

“Our future will be determined in part by the answer to this question: Is Delta as bad as it gets?” Wachter said.

To answer that metaphorical road trip question, we first need to define what we mean by “there.” Fauci says it would be getting to a point where COVID-19 is under “control,” a “low level of infection that doesn’t disrupt society in any meaningful way.”

That’s an accurate description of the malaria situation in some countries in Africa, but it’s nowhere close to where we are here with the coronavirus, my colleagues Rong-Gong Lin II and Luke Money point out.

Getting the outbreak under control would mean having fewer than 10,000 new COVID-19 cases per day across the United States. The most recent figures on the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID-19 Data Tracker indicate the country has had an average of about 92,217 new cases per day over the past week.

That’s less than half the recent peak of 192,185 daily new cases from Sept. 1. But it’s still more than nine times higher than Fauci’s goal.

So, unfortunately, the answer is no. We’re not there yet. And we may not be for quite a while.

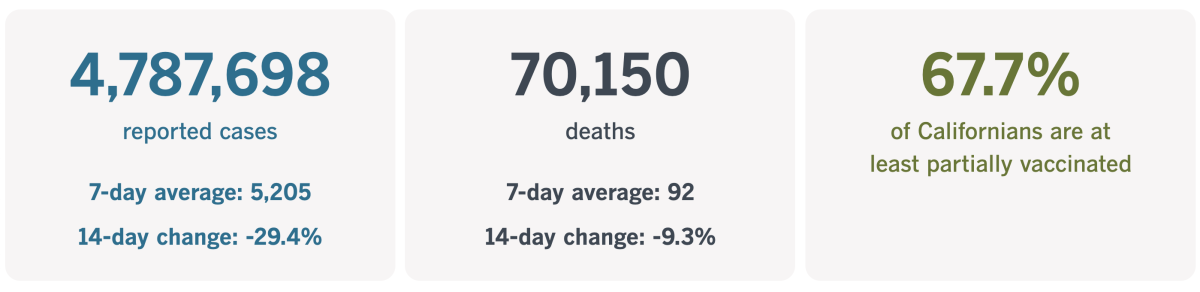

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 3:10 p.m. Friday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

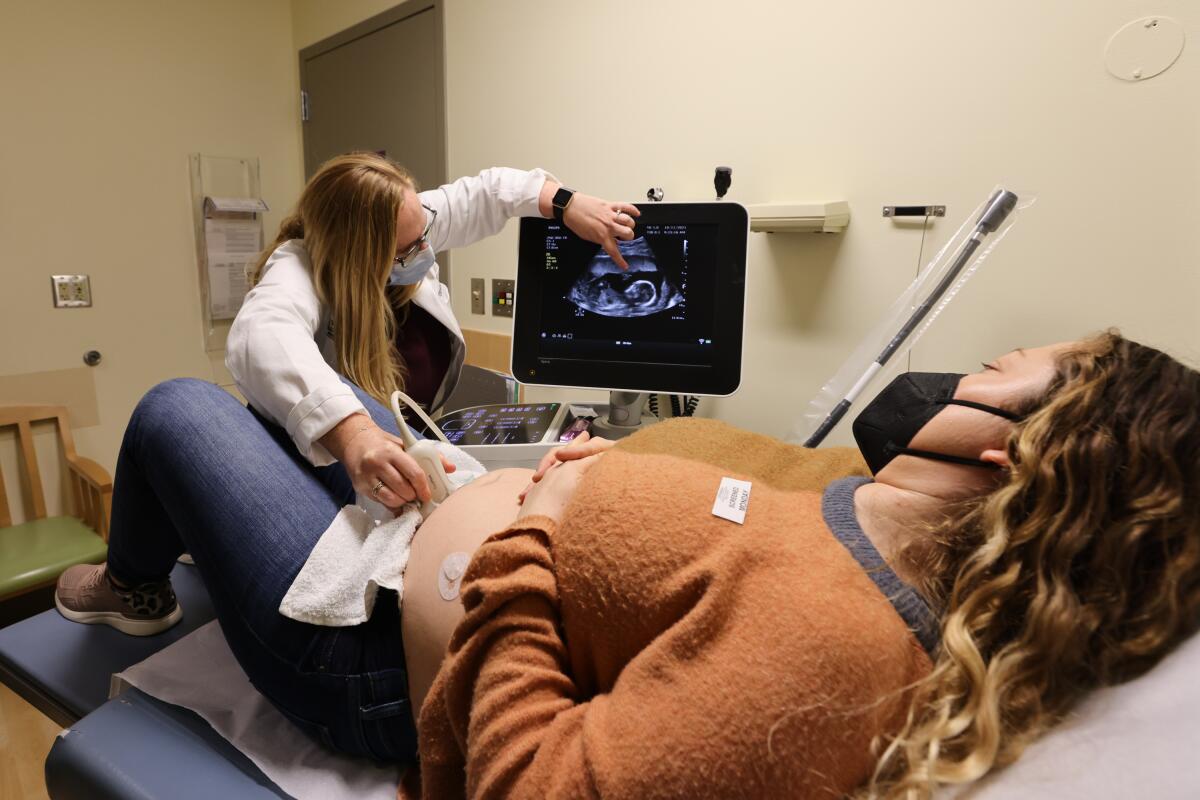

Pregnant people in peril

In the first year of the pandemic, the biggest risk factors for developing a serious case of COVID-19 were older age and having a health condition that would make it easier for the coronavirus to wreak havoc on your body. But after COVID-19 vaccines became widely available, the people most likely to get sick enough to go to the hospital were the ones who opted not to get the shots.

Unfortunately, that put pregnant women at a dangerous disadvantage.

Though the vaccines were being wholeheartedly endorsed for most adults, there was hesitation about recommending them for people who were pregnant. The reason: a lack of clinical trial data showing the vaccines would be safe for women and the developing babies they carried.

The dearth of data was no accident. Pregnant women were routinely excluded from clinical trials. Though it was a well-intentioned sort of exclusion — motivated by the kind of do-no-harm mindset embodied in the Hippocratic Oath — it wasn’t always helpful in the long run if it wound up depriving patients of a much-needed medication.

“The prevailing idea is that pregnant people need to be protected from research,” said Dr. Diana Bianchi, head of the National Institutes of Health’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. “It’s a very paternalistic attitude, and we are trying to change the culture, to protect pregnant people through research, instead of from research.”

Bianchi felt so strongly about this that she and some of her colleagues organized a task force that spent more than two years developing guidelines for safely conducting research in women who were pregnant or breastfeeding. That advice was made public in 2018, and was updated several times to include recommendations on how it could be implemented.

Unfortunately, the guidelines did not make their way to the companies developing COVID-19 vaccines.

Pfizer and Moderna gave pregnancy tests to women being considered for inclusion in their clinical trials and kept out those whose tests came back positive.

Despite those tests, 23 people in the Pfizer trial and 13 in Moderna’s had pregnancies that weren’t far enough along to be detected by the tests, or that began after they got their first injections. The results from these patients were reported to the Food and Drug Administration, but the numbers were too small to offer meaningful guidance to pregnant people trying to decide whether to accept the new vaccines.

The health experts they’d normally rely on weren’t much help either.

In the early days of the vaccination campaign, the CDC said people who were pregnant “may choose to” get a COVID-19 shot, but the agency neither encouraged nor discouraged it.

The World Health Organization, on the other hand, said it did not recommend the vaccines for pregnant people unless they faced a high risk of coronavirus exposure. That stance alarmed both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, who issued a joint statement stressing that the vaccines “should not be withheld from pregnant individuals who choose to receive” them.

Over a period of months, the CDC and the two medical groups went from being neutral on the vaccines to actively encouraging them. That evolution was made possible in part by pregnant women who chose to get vaccinated and allowed researchers to keep tabs on them. The data that emerged from those registries showed the vaccines were indeed safe.

But the delay had tragic consequences for some women who put off getting vaccinated because they were pregnant (or trying to become pregnant) and wound up severely ill — or worse. Even now, two-thirds of pregnant women remain unvaccinated, CDC data show.

Dr. Linda Eckert could see the consequences of this at the University of Washington Medical Center, where she is an obstetrician-gynecologist. As the Delta variant filled the hospital with COVID-19 patients, more of them were pregnant than at any previous point in the pandemic. Some of the expectant mothers were on mechanical ventilators — and a few didn’t make it.

“I have rarely seen any condition confer this much risk to pregnant individuals,” Eckert said. “It’s actually just ... horrifying.”

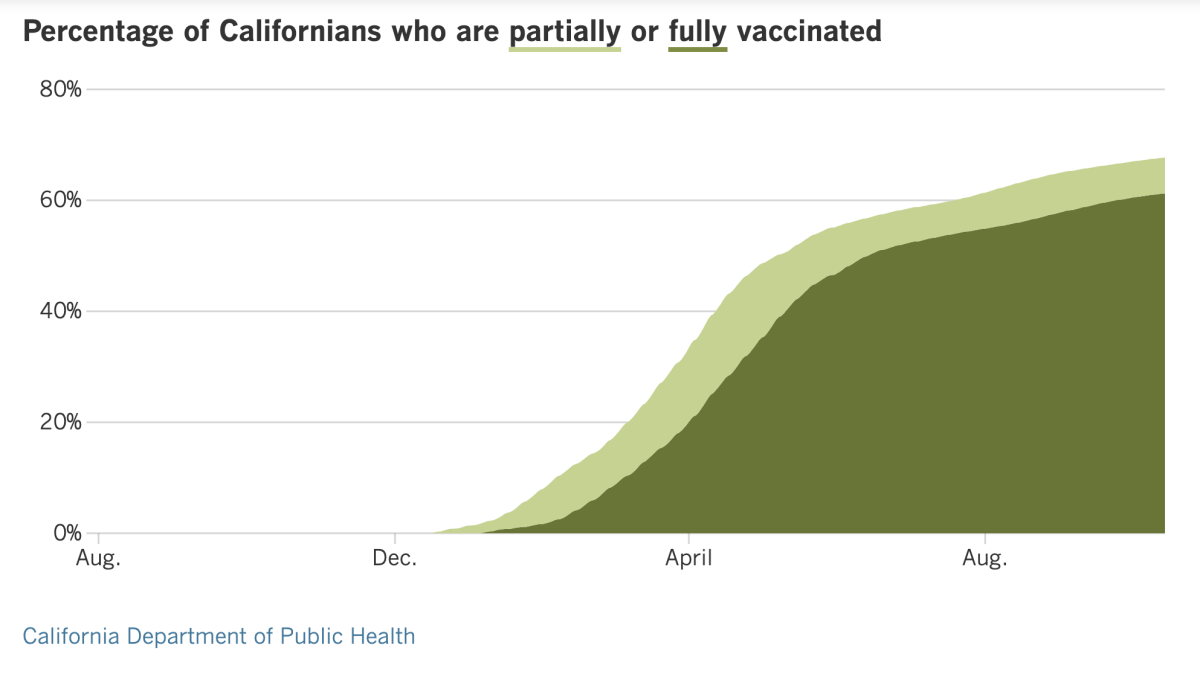

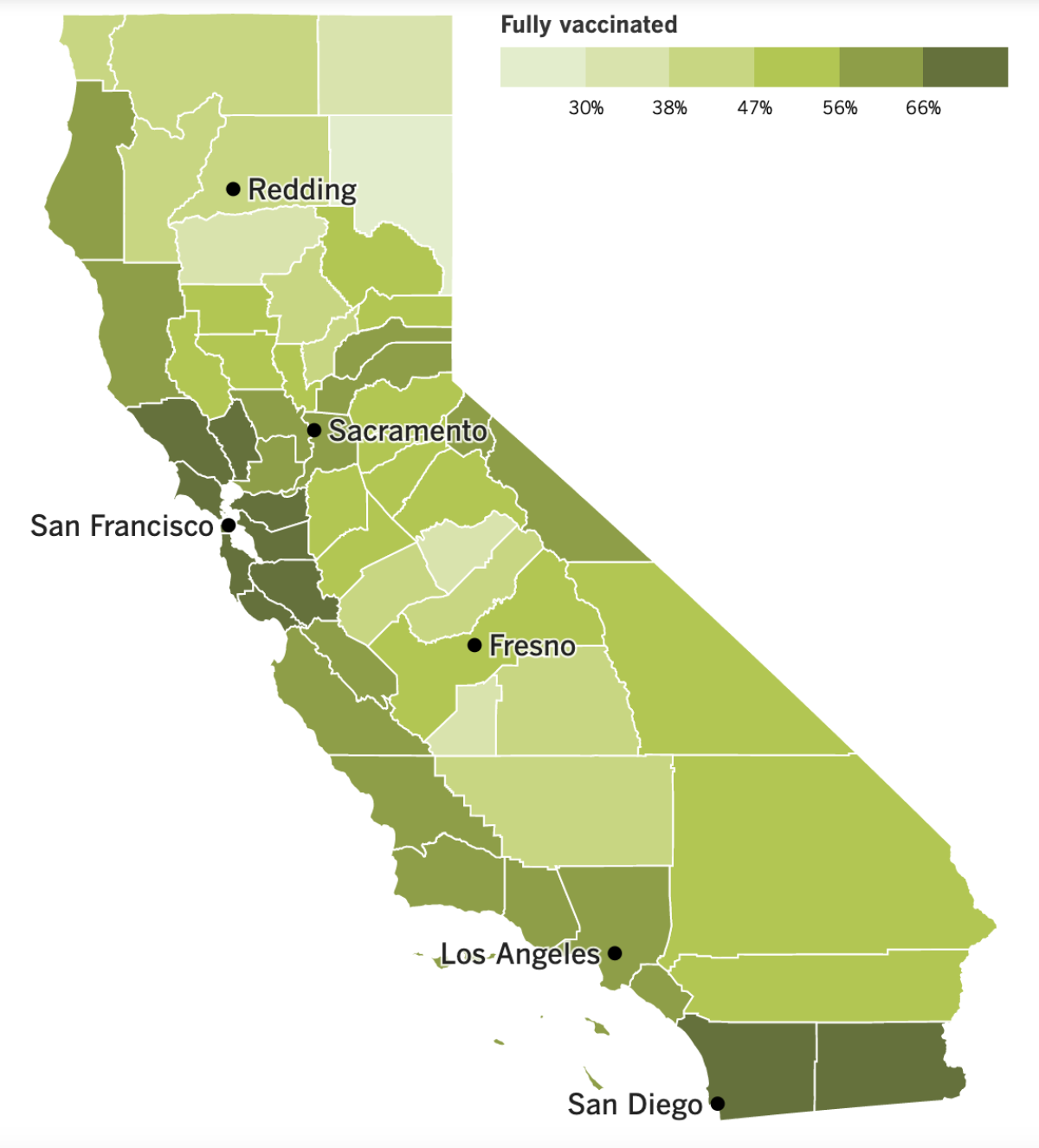

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

Less than two weeks after the U.S. recorded its 700,000th COVID-19 death, California crossed a grim milestone of its own by racking up the 70,000th death in the Golden state.

That means California’s loss is equivalent to emptying an entire mid-sized city like San Clemente, Camarillo or Walnut Creek.

Nearly 12% of all Americans live in California, so it should come as little surprise that the state’s death toll is the highest of any state. However, when measured on a per-capita basis, it ranks 35th among the 50 states, plus Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia.

If you add up all the casualties over the course of the pandemic, California’s COVID-19 fatality rate stands at 178.8 deaths per 100,000 residents. That’s significantly below the 244.7 per 100,000 for Texas, 278.2 per 100,000 for Florida and 284.7 per 100,000 for New York. Mississippi currently tops the list, with 331.2 deaths per 100,000 residents, while Vermont has the lowest cumulative fatality rate at 54.4 deaths per 100,000 residents.

Health officials credit California’s relatively high vaccination rate for keeping people safe, and more Angelenos are getting the shots to comply with vaccine mandates.

The Los Angeles Unified School District announced Friday that about 97% of its teachers and 97% of administrators met its deadline to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19. A day earlier, United Teachers Los Angeles said about 95% of its members — including nurses, counselors and librarians, as well as teachers — were fully vaccinated.

Among the 3% of teachers who haven’t submitted proof of vaccination, it’s unclear how many received an exemption for medical or religious reasons. Even so, the new figures are a big jump from late September, when only about 80% of district employees had sent in proof of vaccination.

L.A. city workers face a Wednesday deadline to get vaccinated in order to keep their jobs. But with just days to go, it remains unclear what will happen to those who don’t comply. Officials have been discussing the matter with employee unions, but no agreements have been reached.

The city already pushed back a deadline for seeking medical or religious exemptions, and the process of reviewing those requests is still ongoing.

We’re heading into the second weekend of L.A. County’s vaccine mandate for certain indoor businesses, and during the first weekend, health inspectors issued a grand total of zero citations for noncompliance.

Instead of writing up the bars, breweries, nightclubs and other businesses that didn’t request proof of vaccination before allowing patrons to be served indoors, the inspectors provided additional training. Of the 129 businesses that were visited, 24 needed some remedial education, the county’s public health department said.

Customers aren’t the only ones who need to get vaccinated. At least one dose is required for employees, and they’ll have to be fully vaccinated by Nov. 4.

Across the country, the county that is home to Tallahassee was fined $3.5 million by the state of Florida for enforcing its local vaccine mandate.

Leon County fired 14 workers who refused to get COVID-19 shots. The Florida Department of Health said that action violated a new state “vaccine passport” law that prevents businesses and governments from requiring proof of vaccination.

The law is being challenged in court. But in the meantime, dozens of local governments, healthcare systems, performing arts centers and others are being sued by the state for disregarding it and requiring proof of vaccination. Among those targeted are the Miami Marlins and an arena that hosted a Harry Styles concert, according to a public records request from the Orlando Sentinel.

In other vaccine news, the group that advises the Food and Drug Administration about COVID-19 shots has had a busy few days.

On Thursday, the panel examined Moderna’s application to offer booster shots to certain groups of people who were at least six months out from their second dose. Their unanimous recommendation was to make the shots available to senior citizens as well as to younger adults who had health problems, jobs or living situations that made them more vulnerable to severe cases of COVID-19.

Those are the same higher-risk groups that are now eligible for a booster dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. But unlike the Pfizer booster, which is identical to the first two shots, Moderna’s proposed booster dose is only half the original.

Panel members emphasized that there was no evidence that either booster should be made available to everyone at average risk.

On Friday, the panel made another unanimous endorsement of booster shots for Johnson & Johnson’s single-dose vaccine. The J&J boosters could be given to adults as soon as two months after the initial dose, the panel said. Some members even suggested the FDA consider the booster a second dose in a two-shot series.

A recent study suggested that as many as 5 million people who received the J&J vaccine had a poor immune response and might be at increased risk of hospitalization if they become infected with the coronavirus. Data like that prompted panel members to set aside some of their concerns about wanting more evidence of the boosters’ efficacy.

Offering a J&J booster “could be a public health imperative,” said member Dr. Archana Chatterjee, dean of the Chicago Medical School.

FDA officials aren’t obligated to follow the panel’s advice, though they usually do. The CDC also has to sign off on the boosters before they’re made available to the public. The CDC’s independent advisory panel will meet to discuss the issue next week.

With the holiday season approaching, the Biden administration is making plans to reopen its borders to international travelers — as long as they are vaccinated.

The White House said Friday that U.S. borders would reopen to foreign travelers starting Nov. 8. Foreign nationals will be able to board flights directly to the U.S. from anywhere in the world if they are vaccinated against COVID-19 and tested negative for a coronavirus infection in the previous 72 hours. That will replace a system that prevented most non-U.S. citizens from entering the U.S. directly from Europe, China, India, Brazil and certain other places.

Foreigners who are not vaccinated can expect to be barred from entering the U.S., while unvaccinated Americans will need a negative COVID-19 test to return home. The policy changes were initially announced last month, but the date for them to take effect is new.

Land borders will also reopen early next month for nonessential travel, the first time that will be the case in 19 months. International visitors will have to be vaccinated against COVID-19 to enter the country from Canada or Mexico by car, bus, rail or ferry. Unlike with air travel, no negative coronavirus test will be necessary.

Essential travelers, such as truck drivers, will also be subject to the vaccine requirement starting in mid-January.

The new policies will mark a shift toward focusing on the risk profiles of individual travelers, rather than the risks associated with the country they’re traveling from.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Does it really matter if I get vaccinated against COVID-19 at this point?

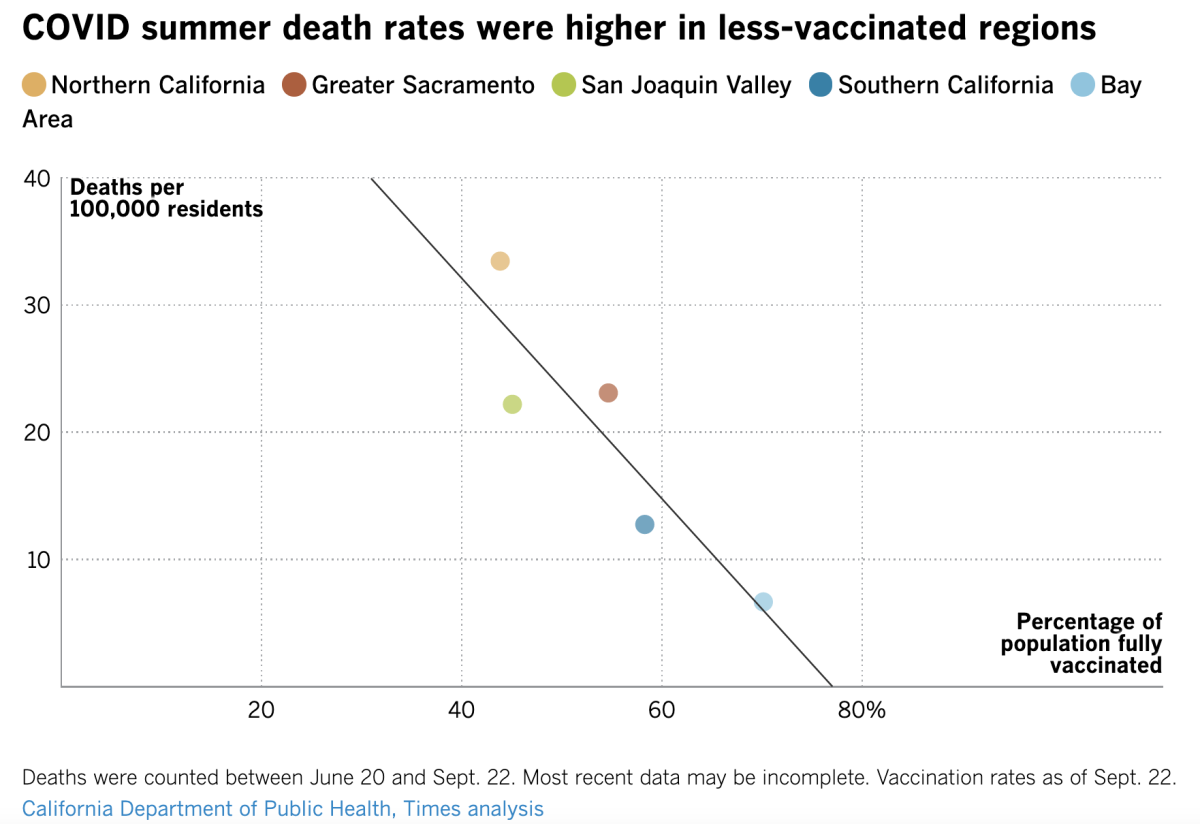

Yes. The higher the vaccination rate in a community or geographic region, the lower the rate of COVID-19 deaths there. In other words, your shot protects not just you but the people around you as well.

California’s experience illustrates this quite well. During the devastating surge of last fall and winter, Southern California’s densely populated urban communities were among the hardest-hit areas of the state. Before COVID-19 vaccines were widely available, the virus spread readily in a target-rich environment.

But the shots have changed the trajectory of the outbreak here. When the Delta wave hit, the places that got hammered were rural and agricultural areas with low vaccination rates.

The graph above shows the relationship between COVID-19 vaccination rates and COVID-19 mortality rates quite clearly. In Northern California, there were 33.4 COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 residents during the summer; by the time the first day of fall arrived, the region’s vaccination rate was just below 44%.

At the other end of the spectrum was the Bay Area, where there were 6.7 COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 residents this summer. On Sept. 22, the region’s vaccination rate was 70.1%.

The way the dots cluster close to the black line indicates that this is not a coincidence.

“The take-home message for everyone is that vaccines save lives,” Dr. Robert Kim-Farley, an infectious-disease expert at UCLA, told my colleagues. “Get vaccinated and save yours and your loved ones’ lives.”

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

That adorable Wheaten terrier with the red leash is Lani, a certified therapy dog. Once a week, Lani visits Kaiser Permanente’s Los Angeles Medical Center to help burned-out staffers recharge and de-stress.

Joyce Leido is Lani’s owner. She is also the medical center’s chief nurse executive, so she has spent a lot of time thinking about the mental state of the caregivers there who have been on the front lines of the pandemic for more than a year and a half. When the death of a COVID-19 patient causes a nurse to second-guess his or her actions, Leido reassures them that they’re doing their best under difficult circumstances — and that’s the most anyone can do.

Leido realized that when she was the one in need of rejuvenation, she could find it in Lani. So she began sharing her four-legged support system with her staff. It’s just one example of the ways nurses have coped with the relentlessness of pandemic. Read this story to learn more; you might be able to adapt some of their strategies to bolster your own mental health.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.