Coronavirus Today: A tale of two Californias

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, Sept. 7. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

At a time when the coronavirus situation in some other states has gone from bad to worse, circumstances in California have stabilized. The number of new cases in the state has hovered between 12,000 and 15,000 per day over the past month. And by Monday, COVID-19 hospitalizations — a lagging indicator since serious cases take time to develop — had fallen for six days in a row.

Though all but three counties (Monterey, Marin and Alpine) still have more than 100 new cases per week per 100,000 residents — enough for transmission to be considered “high” by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — California’s overall rate of 124.3 weekly cases per 100,000 residents is lower than in all other states except for Connecticut, New Hampshire, Michigan and Massachusetts. (The District of Columbia also has a lower rate than California.)

To get a sense of how well California is doing, just take a look at our usual big-state comparators. Texas now has 436.7 new cases per week per 100,000 residents, and Florida has 533.3. What’s more, Florida’s case rate is now the worst it’s been since the pandemic began, while ours is only one-third as high as it was during its winter peak.

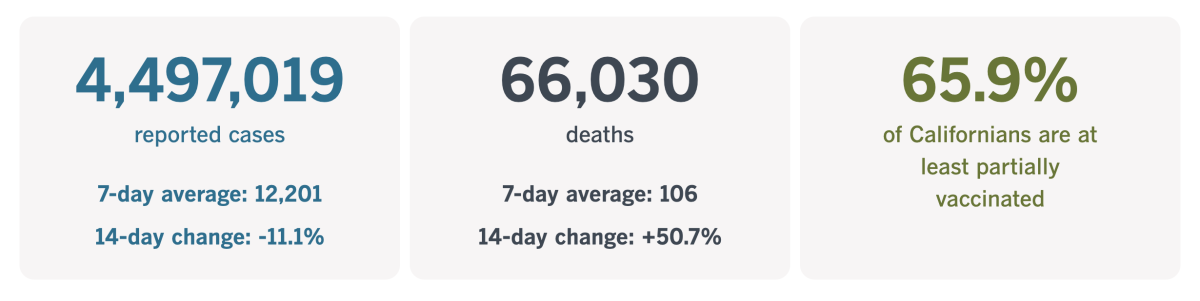

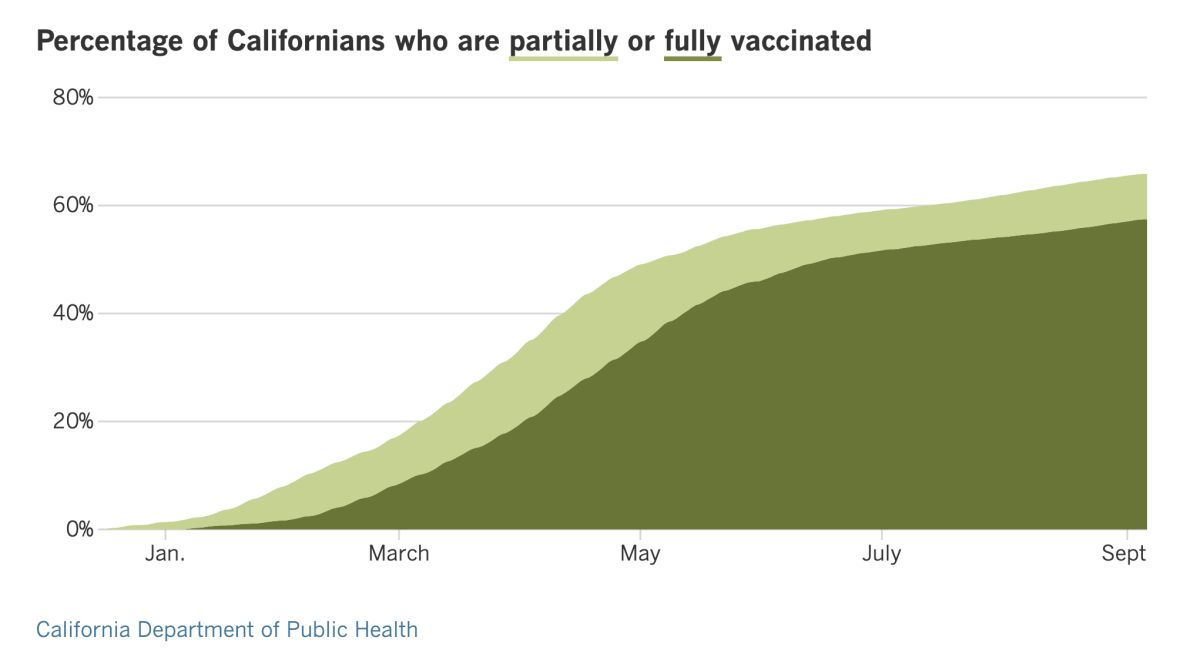

For that, California can thank the 65.9% of residents who are at least partially vaccinated, as well as those who are complying with the indoor mask mandates that have been implemented in the state’s most populous counties.

Even the return of children to school hasn’t led to coronavirus surges in Los Angeles and Orange counties — a testament to the power of face masks, social distancing, hand hygiene and other measures to keep transmission under control.

All that said, some parts of California are doing better than others — much better.

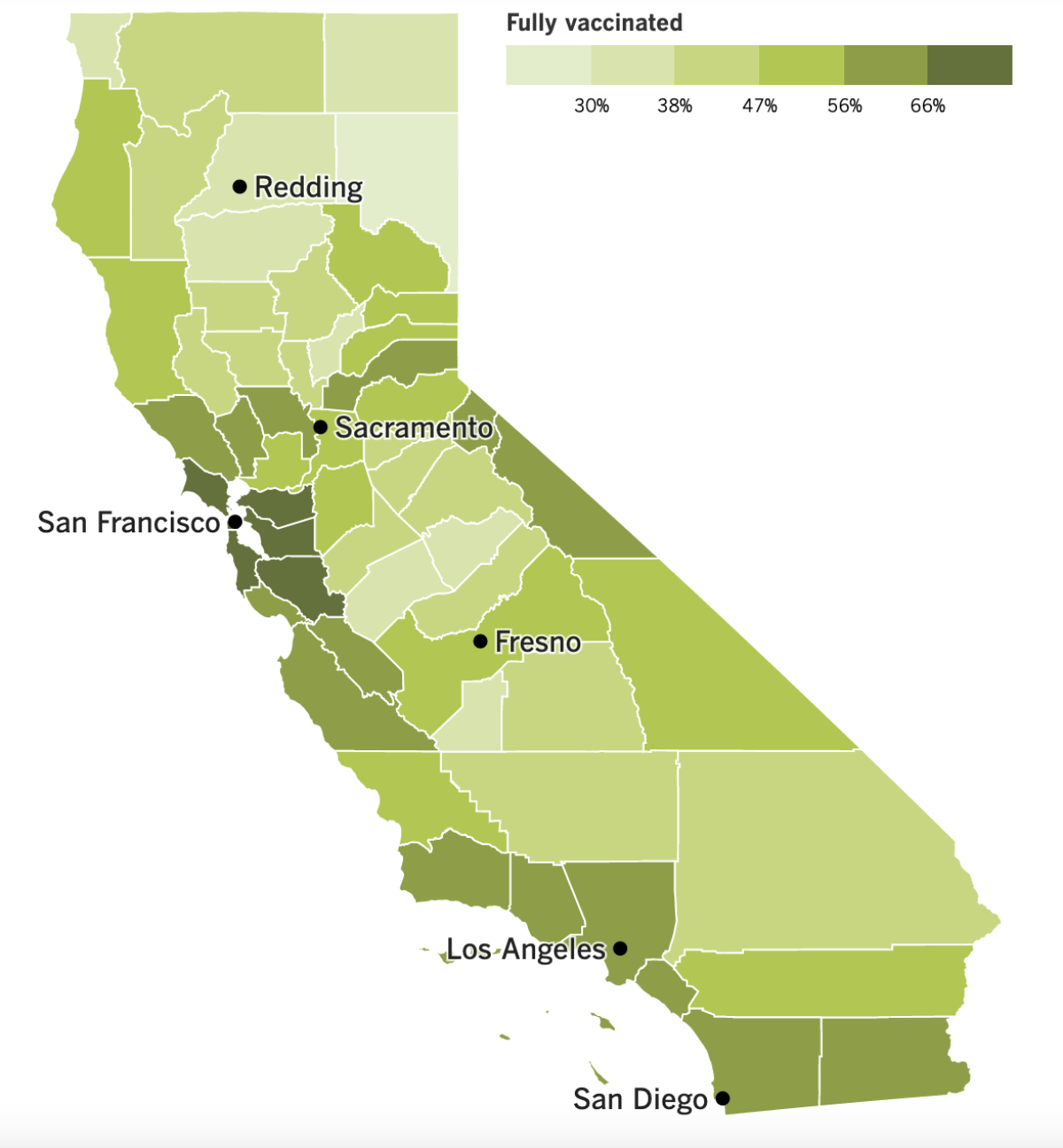

In Santa Clara County, home to San Jose and much of Silicon Valley, 78.4% of residents are at least partially vaccinated and 73% are fully vaccinated. That could well be the reason COVID-19 deaths there have not increased as much as would otherwise be expected given the increase in the county’s coronavirus case rate.

Santa Clara has reported 1.6 COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 residents this summer. Los Angeles, by contrast, has seen 10 deaths per 100,000 residents. Down here, 66.2% of residents are at least partially vaccinated and 58.3% are fully vaccinated.

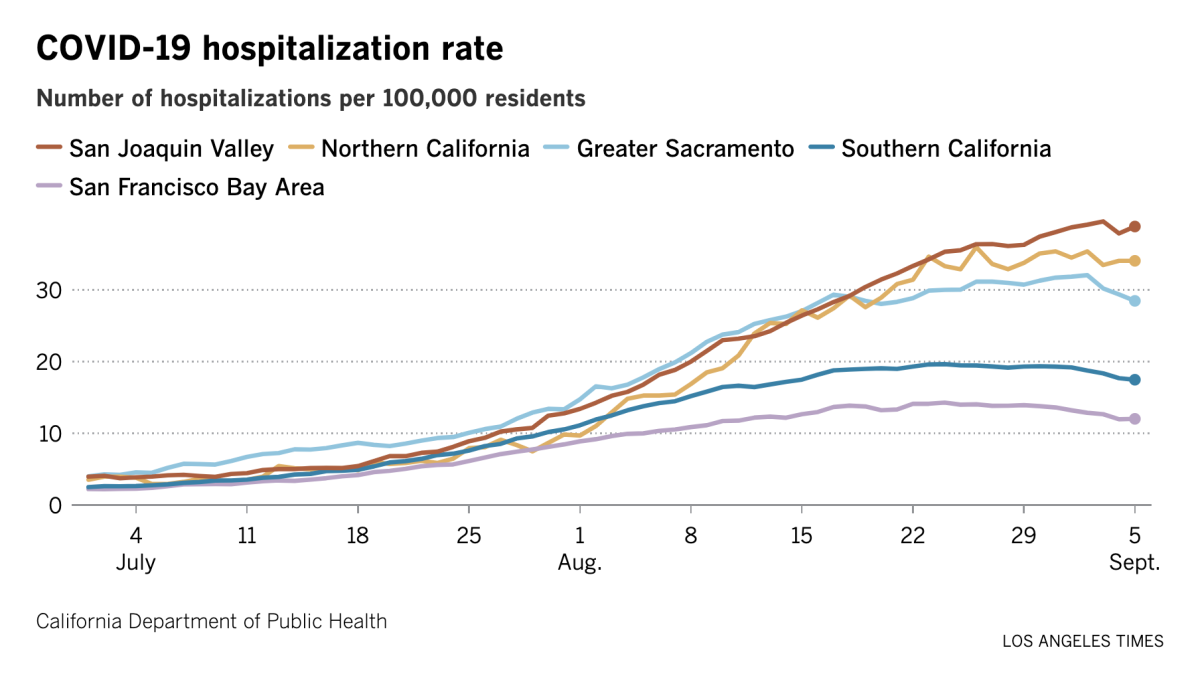

Hospitalizations are also higher in counties where fewer people are vaccinated.

In the San Joaquin Valley, there are 39 COVID-19 hospitalizations for every 100,000 people, and capacity in the region’s ICUs has been below 10% for a week. Fresno and Kern are the two most populous counties there, and their partial vaccination rates are 56% and 47%, respectively.

In California’s rural north, there are 34 COVID-19 hospitalizations per 100,000 people. That region is home to six of the 10 counties with the lowest vaccination rates, including Lassen, where only 23.6% of residents are at least partially vaccinated and 20.9% are fully vaccinated.

The San Francisco Bay Area is at the other end of the spectrum, with 12 hospitalizations for every 100,000 people. Perhaps not coincidentally, the eight counties with the state’s highest vaccination rate are all in the Bay Area: Marin, San Francisco, Santa Clara, San Mateo, Contra Costa, Alameda, Napa and Sonoma.

Battle-hardened health officials know better than to say the worst of this surge is over. The state’s weekly case counts may have leveled out, but they’ve yet to show a sustained drop.

Last year, cases began to rise sharply around mid-October, and that was without students attending in-person school throughout the state. Nor was the Delta variant in the picture.

“We’re not making any predictions in this go-round because there are some things that are still creating additional risk for us,” said Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer.

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 7:08 p.m. Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

When public health meets religion

From the point of view of the coronavirus, a body is a body and a cell is a cell.

If the virus has an opportunity to slip into your airway and look for a cell to latch on to, it will not pause to inquire about your religious beliefs. As long as there are no antibodies around to intercept it, the virus will do its best to connect with its target, set up shop inside, copy itself hundreds of times, and release those viral particles into the body so they can repeat the process.

Since the biology of a coronavirus infection is the same for everyone, you might expect that the public health measures taken to prevent that type of infection would be the same for everyone too. But in the case of vaccine mandates, that’s not necessarily so.

Generally speaking, these mandates carve out exceptions for the very small number of people who have a medical condition or disability that would make the shot unsafe. They also provide an out for people whose religious beliefs make getting the vaccine untenable.

Why would someone’s religious beliefs have anything to do with it?

The production process for Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine involves the use of a cell line that was derived from retinal tissue obtained from an abortion in the Netherlands in 1985. The cell line is used to grow the adenovirus that delivers the vaccine’s payload, but none of those cells — or any other fetal cells — are an ingredient in the vaccine.

The mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna were developed and tested with the help of a different cell line grown from kidney cells obtained from a Dutch abortion in 1973. But those cells aren’t used to make or manufacture the vaccines either.

No less a religious authority than Pope Francis has decreed it “morally acceptable” to get a COVID-19 vaccine. In fact, the pontiff — who was vaccinated along with his predecessor Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI in January — has been encouraging everyone to get immunized as “an act of love” to protect others. Catholic bishops in Los Angeles and other major cities have told priests and deacons not to sign letters requesting religious exemptions.

Members of the Christian Science Church normally turn to prayer instead of medicine when they’re in need of healing. But when it comes to matters of public health, they obey quarantine rules, cooperate with contact tracers, and let officials know if they suspect they have COVID-19. Along those lines, the Church doesn’t oppose members who choose to get vaccinated.

But other churches are issuing such letters by the hundreds. Whether their reasons are based in religion or political ideology is not necessarily clear.

The pastor of a church in the Sacramento-area city of Rocklin, for instance, explained his opposition to vaccine mandates like this: “Nobody should be able to mandate that you have to take a vaccine or you lose your job. That’s just not right, here in America.”

Guidelines from the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission say that employers don’t have to accommodate their workers’ religious beliefs if doing so would cause an “undue hardship.” However, if they can take a “reasonable” action that “eliminates the conflict between religion and work,” they should, the EEOC says.

Exactly what constitutes a “reasonable” accommodation when it comes to COVID-19 vaccines hasn’t been specified. Legal experts agree that offering a religious exemption to a vaccine mandate qualifies — but some go on to say that it’s above and beyond what is necessary.

“Under current law, it is clear that no religious exemption is required,” Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of UC Berkeley’s law school, told our friends at Kaiser Health News.

The U.S. Supreme Court has upheld the right of a state to mandate vaccines since 1905, after Massachusetts passed a law requiring residents to be vaccinated against smallpox to protect the public’s health. The law did not violate the Constitution’s 14th Amendment right to liberty because it was neither unreasonable or arbitrary, the justices ruled in Jacobson vs. Massachusetts.

Just last month, the high court’s newest justice, Amy Coney Barrett, denied a request to block a broad vaccine mandate issued by Indiana University.

Even if religious exemptions aren’t required, defending that position in court can be time-consuming and expensive. That’s why people like Dr. John Swartzberg, an infectious diseases expert at UC Berkeley, expect government officials and employers to keep offering them.

“I have a feeling that not a lot of people are going to want to fight on this topic,” Swartzberg said.

Just look at the recent decision by Los Angeles County and the state of California to pay $400,000 apiece to cover the legal fees of Grace Community Church in Sun Valley, which had challenged rules prohibiting indoor worship during the pandemic. (The county also spent more than $900,000 on its own fees related to the church’s lawsuit.)

Margaret M. Russell, a professor at Santa Clara University School of Law, told my colleague Jacklyn Cosgrove that in her view, “the county was correct on the law.” But with Barrett, a conservative, replacing the liberal Ruth Bader Ginsberg seven months into the pandemic, it was far from certain the county would prevail if the suit went all the way to highest court.

“As I learned in law school,” Russell said, “what really matters is what the majority rules.”

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

In other news ...

Children account for a small fraction of U.S. COVID-19 cases, but the pandemic has hardly left them unscathed. Two new studies issued late last week by the CDC show just how much America’s youngsters rely on the adults around them to keep them safe.

When the adults and eligible adolescents around them are vaccinated in large numbers, younger children are much less likely to wind up in the hospital. The reverse is true as well.

And that’s especially true since the Delta variant came to dominate the coronavirus landscape. Over a seven-week period this summer, the rate at which children were admitted to hospitals with COVID-19 increased by a factor of five. For children under 4, the rate jumped by a factor of 10.

Additionally, hospital admissions and emergency room visits were highest for kids in states where vaccination rates were the lowest, and they were lowest in states where vaccination rates were the highest.

More specifically, pediatric hospitalization rates were four times higher in states such as Mississippi, Louisiana, North Dakota and Georgia, which have some of the nation’s lowest vaccination rates, than they were in states such as Vermont, Massachusetts, Hawaii and Connecticut, where vaccination rates are among the highest.

“What is clear from these data is community-level vaccination coverage protects our children,” said Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the CDC.

Those who are already sold on the value of the vaccines and are looking forward to their booster shots may need to wait a little longer than planned. The delivery of third doses of shots made by Moderna may be delayed beyond the Sept. 20 target because the CDC and the Food and Drug Administration are still waiting for critical data from the company.

An official from within the Biden administration said that the information Moderna sent to the federal agencies wasn’t good enough to warrant a recommendation for booster shots. They requested additional data, but by the time they come in, the soonest the booster shots could begin would be sometime in October.

More than 66 million Americans have received two doses of the Moderna vaccine. The earliest recipients got their first doses in late December and their second doses in late January. After waiting the requisite eight months, they’d be eligible for a booster in late September. Having to wait until October would set them back a few weeks.

Nearly 96 million Americans were fully immunized with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, now known as Comirnaty. Booster data for that shot is set to be reviewed by an FDA panel on Sept. 17, in time for third doses to begin on Sept. 20.

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine wasn’t authorized for emergency use until February, so data on boosters for that shot are still a ways off.

Locally, the union representing Los Angeles teachers has dropped its demand that students who are old enough for a COVID-19 vaccine be required to get one.

Support for vaccinating eligible L.A. Unified students remains strong, according to union President Cecily Myart-Cruz. A vaccine mandate will “keep our schools safer and help protect the most vulnerable among us, including children too young to be vaccinated,” she said.

But the union’s latest contract proposal does not insist on the mandate as part of an enforceable agreement. Instead, it lays out a plan that would require students who are fully vaccinated to quarantine for at least seven days after they’ve been in close contact with an infected person. Students who aren’t vaccinated would have to quarantine for 10 days, according to the union’s proposal.

In non-vaccine news, L.A. County officials have detected 167 cases of people being infected with the coronavirus variant known as Mu. Most of those cases occurred in July.

The World Health Organization classifies Mu as a “variant of interest,” a designation that’s one rung down from the “variant of concern” label given to Alpha, Delta and a few other strains. Mu was first identified in Colombia in January and has spread to at least 38 other countries.

The CDC has not yet joined the WHO in calling Mu a variant of interest. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious diseases expert, said it is rarely seen in the United States, where Delta dominates.

“We’re paying attention to it,” Fauci said. “But we don’t consider it an immediate threat right now.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Should I be worried about the C.1.2 variant?

Not yet — and perhaps not ever.

Scientists are tracking this coronavirus variant, which was first detected in South Africa in May, because its genome contains several mutations that are thought to help other strains of the virus infect cells or evade the body’s defenses. Some of its other mutations could help it succeed in other ways as well, experts said.

A report on the variant posted recently on MedRXiv, a site for sharing preliminary research, said that C.1.2 is evolving at a rate that’s about 70% faster than the current global rate for the coronavirus in general. That got their attention because several variants of concern, including Alpha, Beta and Gamma, also evolved at a higher rate.

Another commonality is that in South Africa, it went from accounting for just 0.2% of viral samples that were genetically sequenced in May to making up 2% of the samples sequenced in July. Beta and Delta behaved similarly in their early days.

But Delta still dominates — and until C.1.2 demonstrates that it can outcompete Delta, it would be premature to say it’s on track to become a true threat.

Indeed, although it has been detected as far away as China, New Zealand and Switzerland, neither the World Health Organization nor the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have labeled it a variant of interest, let alone a variant of concern.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Sign up for email updates, and make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Need more vaccine help? Talk to your healthcare provider. Call the state’s COVID-19 hotline at (833) 422-4255. And consult our county-by-county guides to getting vaccinated.

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.