Coronavirus Today: A new school year in Delta’s shadow

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and I’ll be leading you through coronavirus developments this week. It’s Tuesday, Aug. 3. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

California parents had been looking forward to sending their kids back to school this fall with perhaps some semblance of normalcy. But now, with the highly transmissible Delta variant still spreading across the country, that prospect is looking exceedingly dim.

New evidence shows that Delta can be spread through fully vaccinated people – though the infections among vaccinated folks are far less serious than those who have no protection.

Still, it’s worrying news for parents on the cusp of sending their children back to school: those younger than 12 aren’t yet eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine, and relatively few 12-to-17-year-olds have rolled up their sleeves.

My colleagues Hayley Smith and Deborah Netburn spoke to several health experts about this new dilemma. They said that while parents should be extra careful due to Delta — after all, unvaccinated children are only as safe as those around them — several also said it’s important to keep the risks in context. Kids can go back to school as long as proper precautions are in place.

“Children need to be in school,” said Julie Swann, a health systems engineer at North Carolina State University. “Those of us who have experienced last year, we know it.”

Swann published a report recently that laid out different scenarios for school reopening. Without masking in schools, an additional 70% of children could be infected by the virus within three months.

If masking is required in all schools but there are no other mitigation strategies, she estimated that 40% of elementary school students would be infected within three months.

But if half of the kids show up at school with some kind of protection from the coronavirus— either from vaccines or from a prior infection — her model predicts that up to 25% of the other children will be infected, if everyone is masked.

And in schools that implement both masking and weekly testing, as those in Los Angeles Unified do, an estimated 20% of students are likely to be infected.

So masking and mitigation strategies significantly reduce risk to students, though they can’t eliminate it. Still, Swann said schools should continue to reopen, so long as those measures are in place. Ramping up testing of students and staff, as well as of the community at large, would also help to slow the virus’s spread.

The good news, if it can be called that, is this: Many students have actually gotten used to living that mask life on campus — and for them, a return to classrooms is well worth the inconvenience.

My colleague Melissa Gomez paints a vivid picture of how high school students have adapted to the masking rules: Some go outside to take “mask breaks” and breathe in some fresh air and wipe the sweat off their upper lips. To be heard through sound-muffling masks, they talk louder in class. Even the exhaustion of doing sports conditioning while masked is better than sitting at home.

“It’s become like second nature in a sense,” said Deven Allen, 17, an incoming senior at Lawndale High School. “You kind of can’t leave the house without a mask. You kind of feel naked without it.”

Even many younger kids seem to think that the inconvenience of a mask is well worth it. When Carissa Raia dropped off her 8-year-old for third grade at San Bernardino Unified’s Kimbark Elementary School, she said her child was so thrilled to be back at school that she had no complaints.

“I feel like the kids are more used to it. It’s the parents that are freaking out,” Raia said, noting that her 12-year-old, who started seventh grade, has also become accustomed to wearing masks. “It’s not that big of a deal for us.”

Some student athletes even see a silver lining. Allen, who played club volleyball with a mask on, said that time spent training with a mask has helped his stamina.

“I think it’ll be easier to play in a mask because I already have experience,” he said.

Of course, there are some parents who want to do away with mask mandates — read the story to find out more — but I can’t help but be inspired by the adaptability of these students, and their ability to weather such pandemic inconveniences far better than many of us adults.

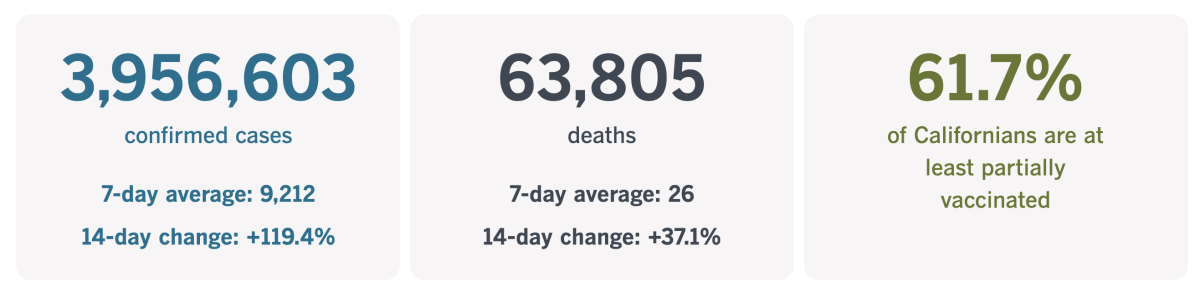

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 10:11 a.m. Tuesday.

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

The vaccine debate roils the Olympics

While the Olympic Games are supposed to bring people together, they’ve become yet another arena for the vaccination debate’s competing arguments of personal choice and collective responsibility.

Last month, American swimmer Michael Andrew revealed that he had not been vaccinated before traveling to Japan for the Summer Olympics — triggering criticism on social media from another prominent athlete, two-time Olympic gold medalist Maya DiRado.

“That Michael would make a decision that puts even a bit of risk on his teammates for his own perceived well-being frustrates me,” the retired swimmer wrote, prompting Andrew’s teammates to push back on the criticism.

“Michael is allowed to make his own decisions and I can guarantee you that none of us here are holding any decision like that against him,” U.S. swimmer Patrick Callan responded in a post.

Other well-known athletes, including gymnast Simone Biles and swimmer Katie Ledecky, have publicly said they’re vaccinated. Andrew is the most prominent U.S. athlete to say the opposite. The 22-year-old from Encinitas said he’d had COVID in December and recovered “very easily.”

“I didn’t want to put anything in my body I didn’t know how I would potentially react to,” Andrew said during a recent news conference. “As an athlete on the elite level, everything you do is very calculated. For me in the training cycle ... I didn’t want to risk any days out.”

And in a recent interview with the Fox Business Network, Andrew argued that he was “representing my country in multiple ways and the freedoms we have to make a decision” and that not taking the vaccine is “something I’m willing to stand for.”

Keep in mind, more than 85% of 709 athletes and alternates on the U.S. roster indicated they had been vaccinated, according to pre-Games medical questionnaires. That’s far higher than the 60% or so of adults in the U.S. but it still means there are more than 100 unvaccinated athletes who are eating, sleeping and training in close proximity with their teammates.

To be fair, the Olympics seems to have spared no precaution. Foreign spectators have long been banned, and domestic fans aren’t allowed inside venues. Plastic dividers on tables in the Olympic Village dining hall keep people separate. Athletes get daily COVID tests. Masks are mandatory, and there are regular temperature checks. Teams leave the country after they’re done competing, and even microphones at news conferences are disinfected between speakers.

It’s a thorny issue, made more so by the fact that many Americans had to qualify for the Olympic team at trials through the spring and didn’t want to risk missing any training because of adverse reactions.

“On one hand, the decisions one makes about one’s health are at the core of one’s autonomy,” said Shawn Klein, who teaches philosophy at Arizona State University and specializes in sports ethics. “These decisions involve one’s deepest values and concerns. A free society must not interfere with such decisions lightly. On the other hand, the decision not to get the COVID-19 vaccine might impact others in potentially serious ways. The balancing of these is always controversial.”

DiRado’s comments, and the response it garnered, offer a snapshot into that debate.

“First, I wish he’d think harder about what he’s proud to represent,” DiRado wrote. “Team USA loves to say that we represent the best country in the world. There are a number of plausible reasons one could give for that, and freedom to not get vaccinated seems to be high for him. OK. But what about the fact that American scientists helped bring the best vaccines to market fastest? And the fact that while much of the world desperately wants vaccines, the US has made them freely available to any citizen who wants one?”

Andrew’s father, Peter, is an assistant for the U.S. team. In an email, he dismissed DiRado’s comments as “people trying to impose their political views” and said, “Try not to take notice of it as how blessed are we to still be living in a country where we have freedom of choice.”

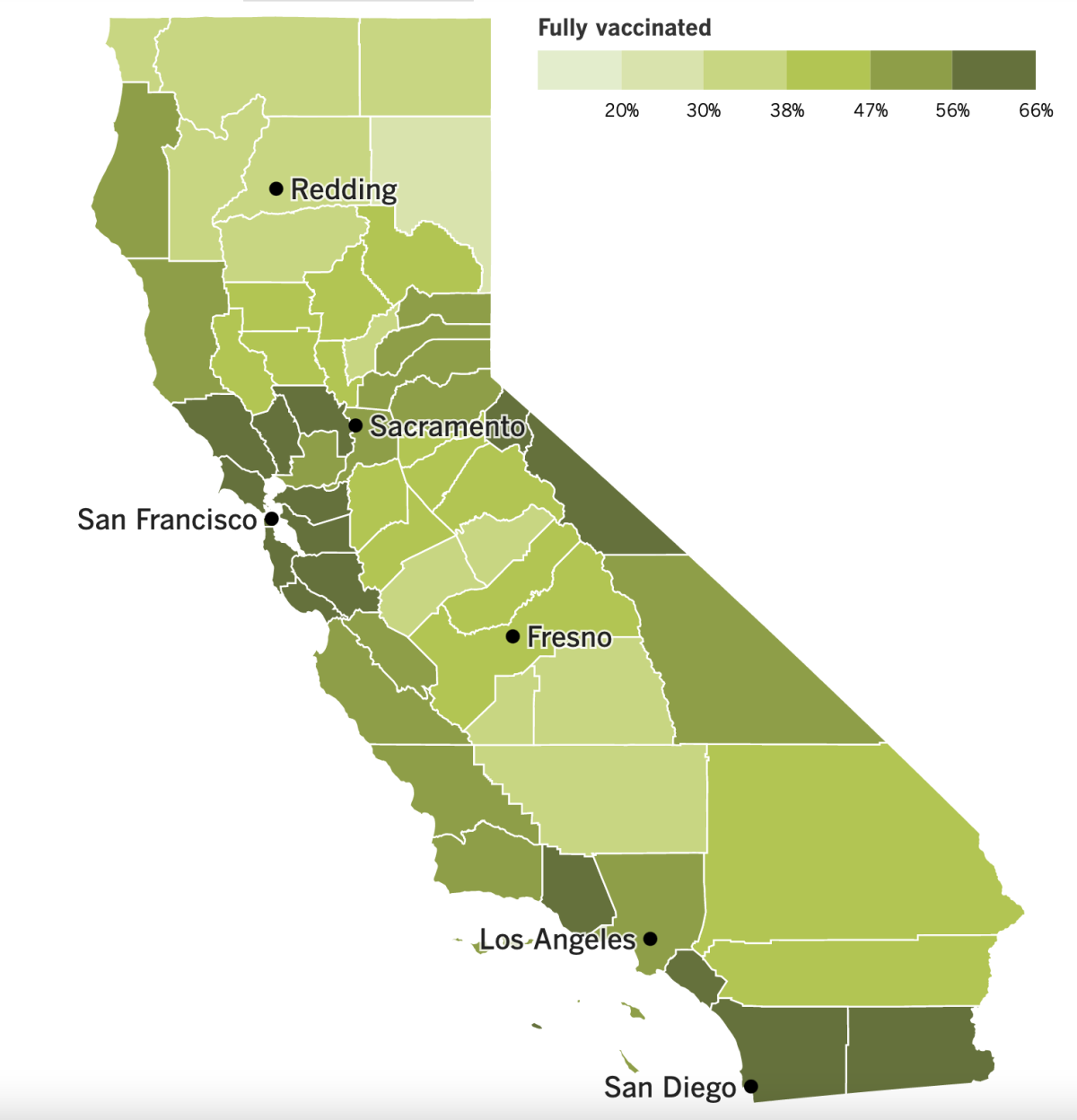

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

In other news ...

Los Angeles County seemed like something of an outlier last month when it reimposed a mask requirement for indoor settings. Some wondered whether officials were getting ahead of themselves. But since then, the Delta variant has spread like wildfire, particularly among the unvaccinated.

A growing number of other counties have since followed L.A. County’s lead. On Monday, seven of nine Bay Area counties plus the city of Berkeley announced a similar mask requirement. Will these mandates help slow the surge? L.A. County, in the vanguard, should be getting their data back soon.

Based on an assessment of transmission rates this week, county health officials said they “will have a more complete picture to inform this discussion by the end of the week.”

Dr. Neha Nanda, medical director of infection prevention and antimicrobial stewardship at Keck Medicine of USC, said cases are still rising, reflecting a gap between the order’s implementation and its widespread adoption. While it might be too soon to see the precise impact of masking, Nanda was confident it would help slow the virus’s spread.

With the mandate in place, “our numbers will not soar,” said Nanda. “They might still rise,” she added, “but it just may not be so exponential.”

In national news, the Biden administration has announced a new temporary eviction moratorium, my colleagues Sarah D. Wire and Eli Stokols report. The new moratorium, which would replace the broader one that expired over the weekend, would take effect in places where COVID-19 numbers have been mounting and would last through Oct. 3, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Without a moratorium, millions of Americans who fell behind on their rent during the pandemic faced eviction, depending on the policies in their particular state.

The moratorium is just part of the issue. States have so far failed to get most of the $46.5 billion that Congress provided in the Emergency Rental Assistance program in January and March to those who need it. According to the Treasury Department, just $3 billion, or 7% of available funds, had been distributed by the end of June.

For its part, California says it has distributed $242.65 million in rental assistance to 20,066 households as of Tuesday — a tiny fraction of the $5.6 billion the state has either received or expects to receive from the federal Emergency Rental Assistance program. Still, it’s more than double where the state was a month ago.

U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham has become the first senator to disclose a breakthrough coronavirus infection after being vaccinated. In a statement issued Monday, the South Carolina Republican said he “started having flu-like symptoms Saturday night” and went to the doctor Monday morning. After testing positive for the virus, Graham said he would quarantine for 10 days.

“I feel like I have a sinus infection, and at present time, I have mild symptoms,” said the 66-year-old Graham, who was vaccinated back in December. “I am very glad I was vaccinated because without vaccination, I am certain I would not feel as well as I do now. My symptoms would be far worse.”

The news comes soon after the CDC updated its guidance to urge even fully vaccinated people to return to wearing masks indoors in areas of high coronavirus transmission due to the contagiousness of the Delta variant. Both congressional chambers have been tightening face-covering rules.

In China, authorities have ordered mass testing, suspended flights and trains and canceled professional basketball games in Wuhan as the Delta variant spreads.

The total number of cases is still in the hundreds in Wuhan, a provincial capital of 11 million people where the virus was first detected in late 2019. Still, they’re far more widespread than anything China has faced since the initial devastating outbreak in early 2020.

While China hasn’t eliminated COVID-19 within its borders, it has managed to curb it with quick lockdowns and mass testing to isolate infected people when new cases arise. Most previous outbreaks didn’t spread too far beyond a single city or province. Now, though, cases are cropping up in more than 35 cities in 17 of China’s 33 provinces and regions.

Most local cases lie in the Jiangsu province, where an outbreak traced to the Delta variant started at the airport in the provincial capital of Nanjing.

Government-affiliated scientists have said Chinese vaccines are less effective against the new coronavirus strains but still offer some protection. More than 1.6 billion doses have been administered, authorities say.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Why does the Delta variant spread so easily?

Since it was first detected in India in December of 2020, the Delta variant has spread around the world. The variant’s relentless sweep across the U.S. — more than 4 out of every 5 infections are now caused by Delta, the CDC estimates — has prompted some readers to wonder what makes it spread so much more easily than its previous iterations.

First, from my colleague Deborah Netburn, the good news: the Delta variant is far less likely to cause serious illness or death in folks who’ve been fully vaccinated against COVID-19. The problem is that it spreads far more quickly and efficiently in the human body than any previous known variant.

Nasal swabs show that people infected with Delta have 1,000 times more virus particles in their upper respiratory systems than those infected with the original, pandemic-causing version.

“That means every cough, every sneeze is packed with that much more virus,” said Dr. Jaimie Meyer, an infectious disease physician at Yale Medicine in New Haven, Conn.

Michael Worobey, a virologist at the University of Arizona, offered a vivid analogy: “If you think of the individual particles as machine gun fire, the Delta variant is shooting at us at 1,000 rounds per second, while previous variants were only shooting at one round per second.”

That may help explain why Delta is about twice as transmissible as the original strain.

Another power-up for Delta: A person infected with this variant can pass it along sooner than a person infected with a different strain.

Originally, it took six days after an initial infection for a person’s body to produce enough virus to infect others, said Chunhuei Chi, director of the Center for Global Health at Oregon State University. Now, the Delta variant has cut that timeline to just four days, allowing to spread through communities even faster than before.

“Delta is different,” said Dr. Joseph Kanter, state health officer of the Louisiana Department of Health. “The transmission dynamics are different. The level of viral load we see in people is different.”

Ultimately, the best way to protect yourself from Delta remains the same as before, scientists say: Get vaccinated, wear a mask and avoid crowded, poorly ventilated areas.

“As a general rule, what would have been an unsuccessful encounter with the virus is now much more likely to be successful,” Worobey said. “That’s why we need to be thinking not just vaccines as protection against this, but back to the mask-wearing we had hoped to put behind us.”

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Sign up for email updates, and make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Need more vaccine help? Talk to your healthcare provider. Call the state’s COVID-19 hotline at (833) 422-4255. And consult our county-by-county guides to getting vaccinated.

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.