Coronavirus Today: To protect and to serve?

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, June 22. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

The Los Angeles Police Department has been using the motto “To Protect and to Serve” since 1955, and the sentiment applies to the city’s firefighters and staffers in the county’s Sheriff’s Department as well. But if these first responders aren’t vaccinated against COVID-19, do they pose a threat to public safety?

It’s a question that might have seemed farfetched back in December, when vaccine doses were scarce and only a select few were eligible to get them. Yet six months later, the state’s first responders are far less likely than other California adults to have rolled up their sleeves for shots.

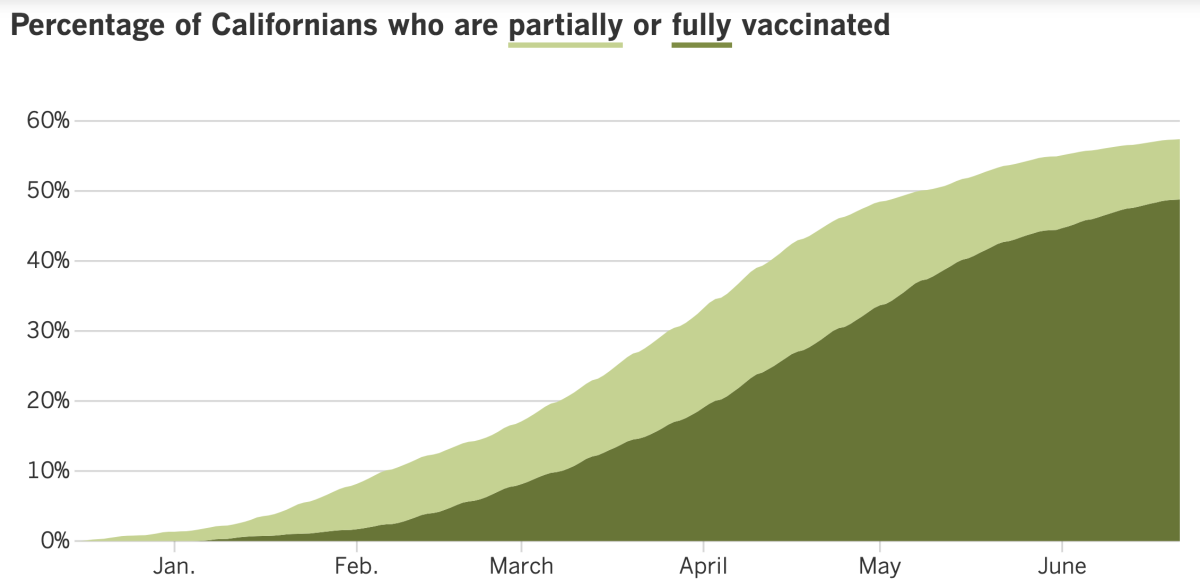

About 72% of California adults have received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, my colleagues Kevin Rector, Richard Winton, Dakota Smith and Ben Welsh report. So have 64% of Los Angeles residents ages 16 and older.

Those numbers are so low that the state is dangling $116.5 million worth of prizes in front of vaccine-hesitant people to get them off the fence.

But the general public’s vaccination rate looks great compared with the stats put up by first responders.

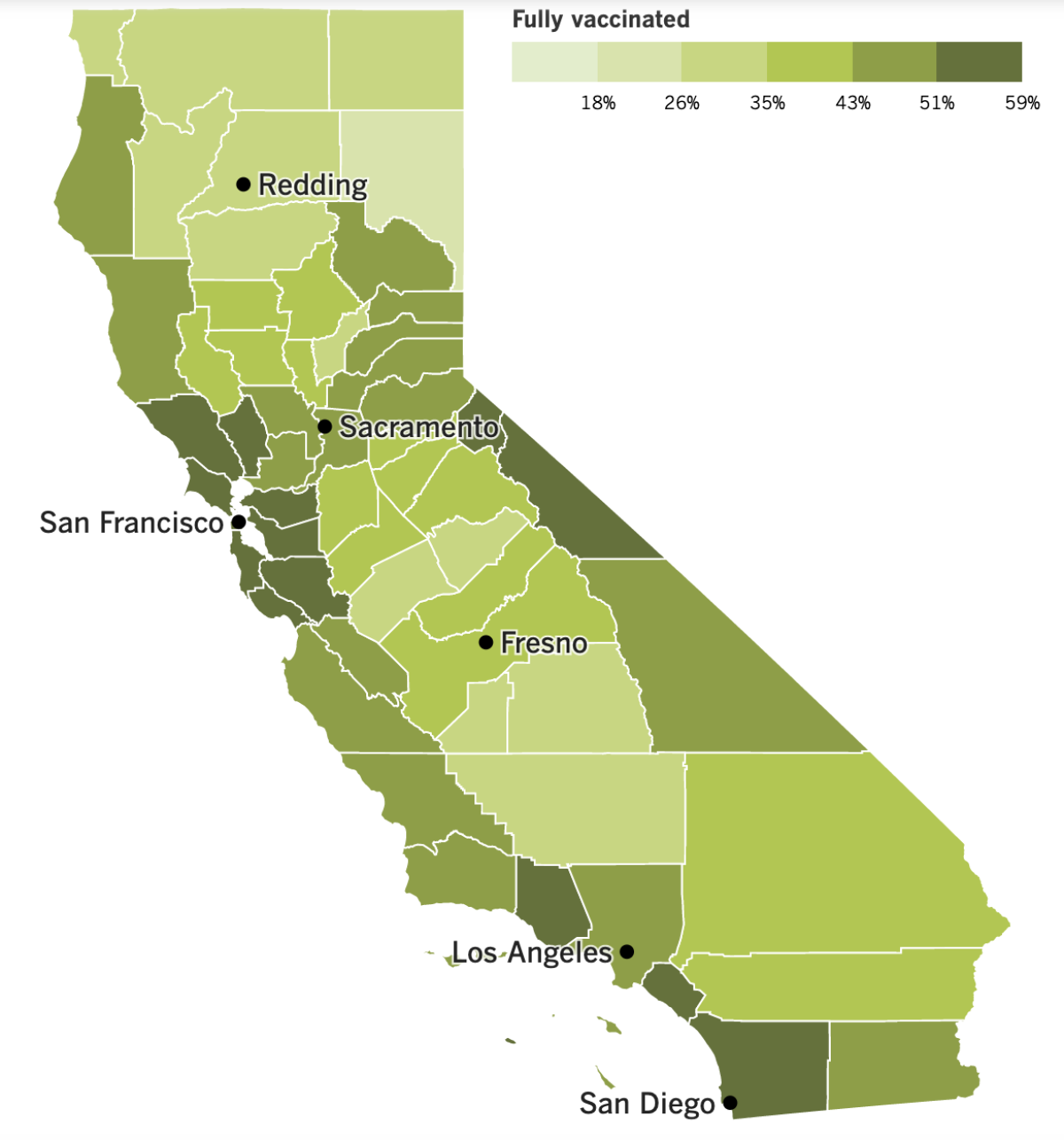

Just 52% of LAPD officers are at least partially vaccinated, as are only about 51% of L.A. firefighters.

Across the state, about 54% of prison employees have begun their COVID-19 immunizations. At some sites, COVID-19 vaccines are so unpopular that only 24% of the staff is known to be fully vaccinated.

This despite the fact that nine LAPD personnel, two city firefighters, and 28 state corrections workers have died of COVID-19. Across all these agencies, more than 20,000 people have been infected with the coronavirus.

There’s general agreement among ethicists, activists and law enforcement experts that first responders should get to make their own health decisions. But the fact that so many have taken a pass on the COVID-19 vaccines has become a growing source of tension among city officials, public safety leaders and their rank-and-file workforces.

Police officers, firefighters and sheriff’s deputies regularly interact with the public — often in confined spaces like courthouses and jails, and with the state’s most vulnerable residents. Community leaders told my colleagues they think public safety officers have actually made the public less safe by spreading the virus.

The first responders’ reasons for avoiding the vaccine are similar to those cited by many Americans. Some feel they’ve got enough immunity thanks to a past infection. Some aren’t convinced the vaccines are safe, or necessary. Some lean to the political right, where the vaccines have been ridiculed or wrapped up in conspiracy theories.

Whatever the reason, the stagnant immunization numbers have some officials contemplating COVID-19 vaccine mandates. On Tuesday, the L.A. Police Commission asked the LAPD to examine the feasibility and legality of a vaccine mandate for officers and report back on the findings. If the shots aren’t required and officers are allowed to work without wearing masks, “one could argue that we’re endangering the public,” said Commissioner William Briggs.

Miami Police Chief Art Acevedo, who heads the influential Major Cities Chiefs Assn., agrees that the country can’t afford to see the vaccination numbers stay flat: “As first responders, that’s a significant public health issue. It isn’t only a matter of their health, but others they come into contact with daily.”

Bioethicist Arthur Caplan of NYU’s Grossman School of Medicine said he hopes vaccine mandates can be avoided by getting public safety employees to see that getting the shots is just another way for them to protect and to serve.

“These folks make a living trying to help other people,” Caplan said. “If we point out that they can maybe help other people by getting vaccinated, that will maybe get more pickup.”

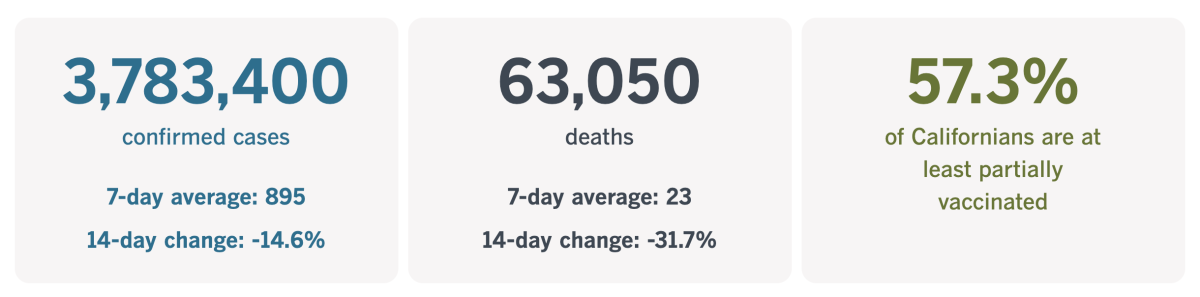

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 5:39 p.m. Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

How the pandemic is changing our tolerance for traffic

Before the pandemic, it took Dale Sieverding 60 minutes to get from his job in Santa Monica to his home near the Grove.

“I hated the evening drive home in the past,” said Sieverding, director of worship at St. Monica Catholic Community. “No matter if I came home at 2 o’clock or 7 o’clock, it was an hour.”

He didn’t miss that commute during the 14 months he worked from home. But now that he’s fully vaccinated, he’s driving back and forth to the church three days a week. Ideally, he told my colleague Andrea Chang, he’ll keep logging the rest of his hours remotely.

We all learned the hard way that it takes a global pandemic to do away with L.A.’s notorious traffic. It’ll be harder still to emerge from the pandemic without bringing the gridlock back. (It may take an act of divine intervention.)

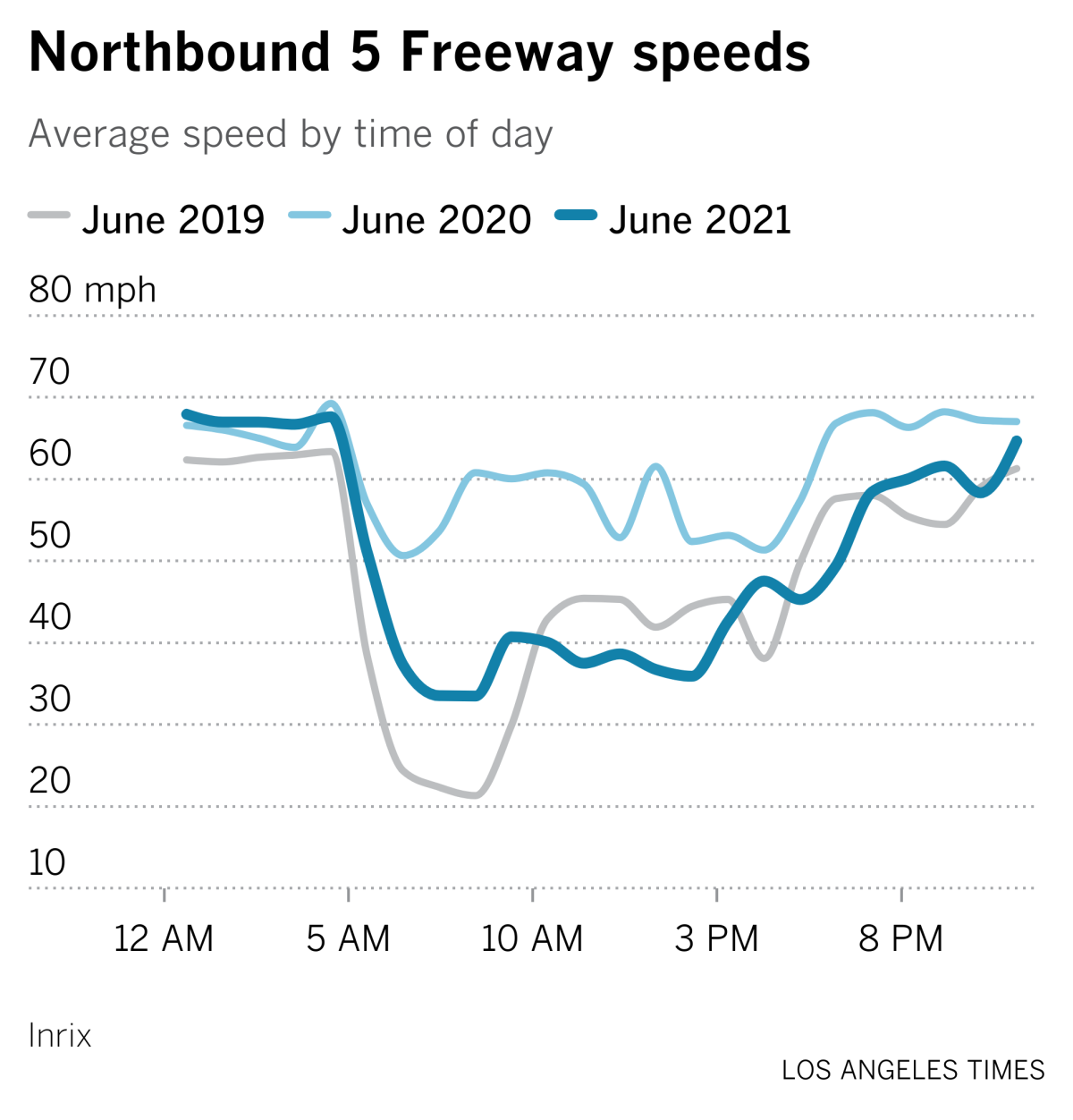

Even before the state officially reopened on June 15, freeways were clogged with cars, and congestion was approaching pre-pandemic levels. But traffic flows on the region’s major arteries have changed. Morning commutes are still quicker than they were before the shutdown, but afternoon drives now creep along like old times. In some places, at certain times of day, the traffic is actually worse.

Consider I-5 North. In June 2019, a driver on the road at 10 a.m. could travel at an average speed of 43 miles per hour. A year later, when we were supposed to be staying at home, a driver’s average midmorning speed was 61 mph. This month, it has slowed all the way down to 40 mph.

So much for those wild predictions — or wishful thinking — that the coronavirus would reduce L.A.’s traffic once and for all. But that doesn’t mean we’ll all go back to our previous commuting routines.

Some workers, like Sieverding, are negotiating arrangements that will allow them to work from home at least some of the time. Others, like Tiffanie Trinh, an IT support technician for Taco Bell, are moving closer to their offices. And as we discussed last week, the boldest among us are quitting jobs that involved spending too much time on the road.

When people complain about “traffic,” they’re typically talking about two distinct things, Brian Taylor, director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at UCLA, explained to my colleague Hayley Smith. The first is vehicle travel — how much people actually drive. The second is congestion, which causes those frustrating delays when lots of people are going to the same place at the same time.

“If we go back to pre-pandemic living and working patterns, driving and traffic levels are likely to be similar to before,” Taylor said. But if enough of us change our living and working patterns, some of the pre-pandemic congestion may be averted.

There are reasons to be hopeful. At least 70% of U.S. workers say they’d prefer to keep working from home at least some of the time, according to a recent survey by the Society for Human Resource Management. Employers are bound to accommodate at least some of those requests. (If you want yours to be one of them, check out our guide to persuading your boss to let you work from home forever.)

In addition, commuters who aren’t eager to spend so many hours behind the wheel may be willing to give mass transit a try. In L.A., Metro took advantage of the pandemic’s reduced traffic volume to install more bus lanes. Another incentive to leave the car at home: Many parking spaces have been given over to outdoor restaurant dining.

With any luck, our freeways will wind up looking more like this:

than like this:

By the way, if you need a refresher on how to cope with traffic and its dreaded cousin, parking, check out this column from Mary McNamara and learn from her mistakes.

California’s vaccination progress

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

In other news ...

Coronavirus case rates are improving across L.A. County, but as usual with the pandemic, Black and Latino residents are faring worse than white and Asian American residents.

When calculated over a two-week period, case rates for the county’s Black residents fell by 13% over the past month and by 22% for Latinos. That sounds good until you consider that during the same period, case rates dropped 33% for white Angelenos and 45% for Asian Americans.

A similar pattern can be seen with hospitalizations: Over the past month, they’ve dropped 11% for Black residents, 34% for Latino and white residents, and 50% for Asian American residents.

“As the weeks pass, we are seeing significant decreases — which is great — in our overall rates, but they also are not distributed equally among racial and ethnic groups in our county,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said.

Speaking of significant decreases, L.A.’s overall recovery has been so dramatic that by the end of last week, the county was reporting about two COVID-19 deaths a day over the previous seven days. That’s down from a peak of 241 deaths per day in January.

Here’s another way of looking at it: The nine counties that make up the Bay Area — Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, Napa, Santa Clara, San Francisco, San Mateo, Solano and Sonoma — were reporting four deaths per day over the past seven days, down from a peak of 63. And there are only 7.7 million people in the Bay Area, while L.A. County alone tops 10 million.

The Bay Area was the coronavirus’ first stop in California, and the first known American COVID-19 fatality was a San Jose resident who died Feb. 6, 2020.

But L.A. County’s COVID-19 death rate overtook the Bay Area’s less than two months later, on April 4, according to a Times analysis. When the outbreak was at its worst, L.A. County was reporting 2.39 deaths per day per 100,000 residents, while the Bay Area reported 0.82.

It took until June 11 for L.A. County to have a lower COVID-19 death rate than the Bay Area, my colleagues Rong-Gong Lin II, Luke Money and Sean Greene report. As of Thursday, L.A. was reporting 0.02 deaths a day for every 100,000 residents, compared with 0.06 in the Bay Area.

What accounts for L.A.’s improvement? Some of it is due to vaccines: 57% of residents of all ages are at least partially inoculated, better than the national rate of 53%. The county also acquired significant immunity from the brutal COVID-19 surge that began in November. Late last month, the L.A. County Department of Health Services estimated that nearly 40% of residents had immunity through coronavirus exposure.

The truly sad part is that we could have made it to the other side without losing so many lives. Just look north: The Bay Area has reported 81 COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 residents over the entire course of the pandemic, while Los Angeles has had 242 deaths per 100,000 residents.

Santa Clara County, which includes San Jose, was the first in the state to adopt COVID-19 rules. Now it has passed a not-at-all-grim milestone. As of Monday, all of its local COVID-19 health orders had been phased out.

Dr. Sara Cody, the local health officer and public health director for the county, said the rules were no longer needed because residents there have embraced COVID-19 vaccines. Four out of five residents who are old enough to be vaccinated have received at least one dose, and among residents of all ages, 71% are at least partially vaccinated.

Nationwide, the number of daily COVID-19 deaths dipped below 300 for the first time since March 2020. According to trackers at Johns Hopkins University, average deaths are about 293 per day — well below the mid-January high of more than 3,400.

New cases have also dropped dramatically. They’re now running at an average of 11,400 a day. In early January, the country was reporting more than 250,000 new infections per day.

The U.S. donated more than 1.3 million doses of Johnson & Johnson’s single-shot COVID-19 vaccine to Mexico, and they have started going into arms in Tijuana and elsewhere in Baja California. The Mexican state became the first in the country to make vaccines available to all adults.

It’s part of a strategy that could speed the reopening of the U.S.-Mexico land border crossing, which has been closed to nonessential travel since March 2020.

“We want to vaccinate the population of the 39 municipalities along the northern border so that the border can be opened as soon as possible,” Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said Thursday when the campaign got underway. “That is the goal.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: What should I do if my COVID-19 vaccine record doesn’t show up in the state’s digital system?

First off, know that you’re not alone. As of Monday afternoon, nearly 70,000 troubleshooting forms have been submitted to the California Department of Public Health. (I’m personally responsible for several of them.)

But that doesn’t mean you should give up. Californians have generated more than half a million digital COVID-19 vaccine records through myvaccinerecord.cdph.ca.gov — and you can join them, with a little perseverance.

People who’ve been vaccinated in the Golden State are supposed to be able to access their records by typing in their first and last names, date of birth and the cell phone number or email address they shared when they got their shot. If any of that information was entered into an immunization registry system incorrectly, no match will be found.

Problems can also arise if a person’s record is already associated with an old (and perhaps long-forgotten) phone number or email address. Some readers have told us their entries appear to be missing altogether.

Whatever the problem, the way to resolve it is to submit the correct information to the state using an online troubleshooting form. You’ll be asked to type in your name, date of birth, cell phone and email address. Then you’ll have to wait two to three weeks for staffers to review the new information, determine whether it’s legit and send you an email letting you know that fixes have been made.

When the state unveiled the digital vaccine record system on Friday, those looking to fix errors were asked to upload a photo of their Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 vaccination record card, along with a photo ID. Now the state will request them only when needed, said Sami Gallegos, press secretary for the state’s COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force.

If you’d rather try to straighten things out over the phone, you can call a state hotline at (833) 422-4255. Additional troubleshooting tips are available at cdph.ca.gov/covidvaccinerecord.

And if you really want to, you can forget about the whole thing. The digital records aren’t mandatory; they’re intended to be “a convenient backup” for paper cards that are misplaced, said Dr. Erica Pan, the state epidemiologist.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Sign up for email updates, and make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Need more vaccine help? Talk to your healthcare provider. Call the state’s COVID-19 hotline at (833) 422-4255. And consult our county-by-county guides to getting vaccinated.

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.