Coronavirus Today: California’s new vaccination milestone

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Thursday, April 1. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

With 18 million shots delivered into waiting arms, California has hit a promising milestone: More than 30% of residents are now at least partially vaccinated against COVID-19.

To be clear, that’s far short of the share needed to reach herd immunity. Experts estimate the percentage will need to be as high as 85% to help stop the pandemic in its tracks. But the share of Californians vaccinated should rise even higher as the state cranks the doors to eligibility wide open.

Still, officials are worried that a rise in coronavirus cases in other parts of the country could make its way to the Golden State — making even the partial protection of one shot a crucial layer of defense.

For those 50 and older who became eligible today, it may also offer a taste of much-needed relief.

“Today’s an important day, obviously, with the opportunity now for people my age that have been waiting,” said Gov. Gavin Newsom. The 53-year-old received his first and only dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine at Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza.

Dr. Mark Ghaly, California’s health and human services secretary, delivered the shot. Then Newsom flexed and waved his vaccine card in the air before heading out for a required 15-minute observation period. Yolanda Richardson, secretary of the state’s Government Operations Agency, also got her shot Thursday.

At the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza site, the atmosphere, though quiet, was festive. One woman walked outside clapping, holding her vaccine card in the air, as her husband waited to hug her. Others smiled beneath their masks as they got their temperatures checked at the door.

It’s true that by raw numbers, California’s delivery of 18 million doses dwarfs that of any other state, including second-place Texas, with just under 12 million. When you account for population, though, our performance looks less than stellar.

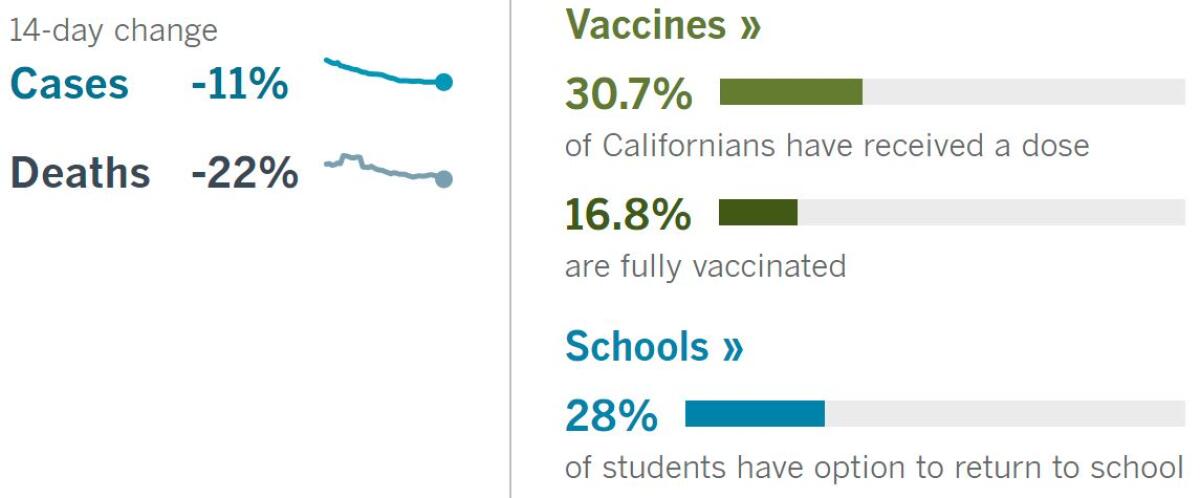

According to The Times’ vaccinations tracker, 30.7% of Californians had received at least one vaccine dose as of Thursday. That beats the national rate of 30% but leaves us still far from the top of the pack, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Consider New Mexico, where 38.7% of residents have gotten at least one shot. So have 36.8% of people in New Hampshire and 36% in Connecticut. The nation’s most populous states haven’t made as much progress: The share of total population that has received at least one dose is 32.4% in Pennsylvania, 31.4% in New York, 28.5% in Florida and 26.4% in Texas.

Even more Californians become eligible April 15, when the vaccine line opens up to anyone 16 or older. If you’re trying to find out how to get a shot, The Times has collected its reporting on how to get that vaccine appointment across Southern California here.

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 5:50 p.m. Thursday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Across California

The rapid expansion of vaccine eligibility could prove to be the biggest test yet for the state’s vaccine effort, which after a rocky rollout has recently stabilized. The question is twofold: As eligibility allows vaccine demand to pour in, will the supply of appointments and doses be able to keep up — and will the process get any less confusing?

For most folks, securing a dose will probably involve diving into California’s array of appointment websites run by a constellation of local health departments, private health providers and clinics, several major pharmacy chains and the state, through a portal known as My Turn.

My Turn suffered from glitches at the start of the vaccine rollout, and just 2 million of the state’s 18 million administered doses have been booked through the platform. As vaccine supply and appointment availability have improved, the issues have lessened. But as a patchwork of websites has sprung up to meet growing demand, some counties and people have abandoned My Turn altogether.

Billed as a one-stop shop for an appointment, My Turn does not include slots from many of the state’s biggest providers, including health chains such as Kaiser Permanente, retail pharmacies such as CVS and Walgreens, third-party providers such as Carbon Health in Los Angeles and Othena in Orange County, and smaller clinics that operate on a platform called CalVax.

“It is a genuine challenge to find an appointment,” said Echo Park resident David A.L. Venable, 29, whose severe asthma puts him at high risk for COVID-19. “That My Turn is a pain and challenge to navigate to this extent does not bode well for the expansion.”

Throughout the pandemic, researchers have tallied the ways that COVID-19 has disproportionately affected Black and Latino Americans. But a recent study in two L.A. medical centers suggests that the pandemic has worsened healthcare disparities for Black patients who don’t have COVID, too.

Hospitalizations for health problems that could have been avoided fell dramatically among white people in the Los Angeles area in the first six months of the pandemic — but they hardly fell at all among Black residents, according to a study published last month in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

The researchers found the disparity after analyzing records at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center and the UCLA Santa Monica Medical Center in 2019 and 2020. They focused on conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, congestive heart failure, pneumonia, uncontrolled diabetes and urinary tract infections. With proper preventive medical care, all of these conditions can often be managed successfully enough to avoid hospitalization.

The discrepancy is a sign that Black patients may be getting poorer access to outpatient care — the kind that could have helped maintain their health and prevented it from deteriorating to the point of landing them in a hospital bed, said Dr. Richard Leuchter, an internal medicine resident at UCLA Health and one of the researchers who led the new study.

Music festivals could return to Southern California as soon as July, my colleague August Brown writes. Live Nation organizers announced this week that Hard Summer would return July 31 and Aug. 1 at the National Orange Show Event Center in San Bernardino. The fest, a staple for EDM and hip-hop, would be one of the first large-scale music events to resume operation in the L.A. area.

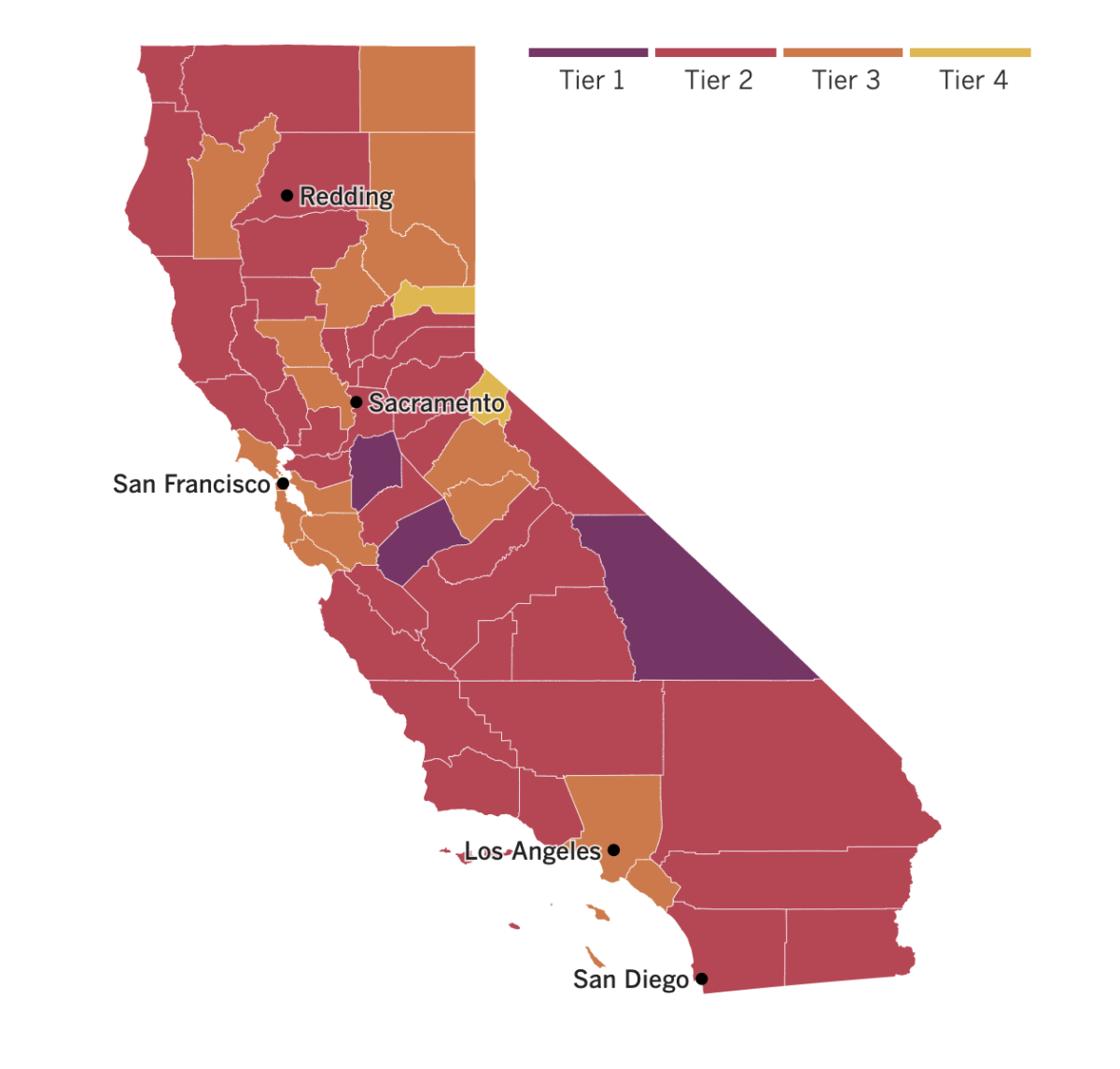

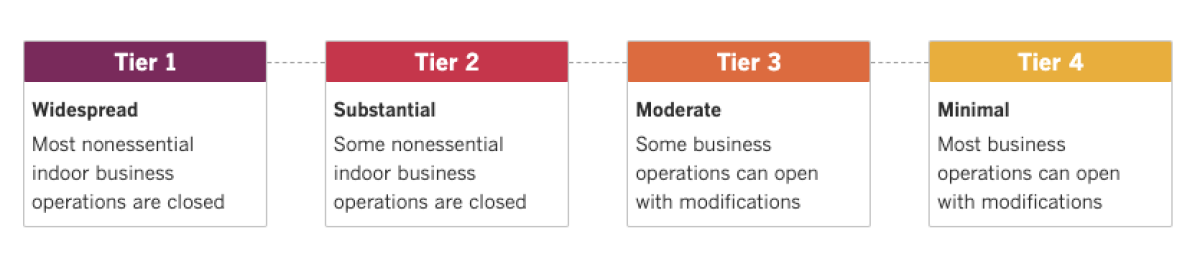

Representatives for the festival declined to talk in depth about any COVID-19 safety protocols. Ultimately, though, its status will depend on where San Bernardino County lies on the state’s four-tier, color-coded reopening plan. Concerts would be allowed under the state’s orange, or second-least restrictive, tier at an outdoor-only 33% capacity.

Currently, San Bernardino County is in the red tier, but Los Angeles and Orange counties entered the less restrictive orange tier Tuesday (though L.A. is holding off until April 5 to ease restrictions). In the least restrictive tier, yellow, outdoor concerts could resume at 67% capacity, while indoor shows would still be forbidden.

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

There’s a new roadblock for the national vaccination ramp-up: A batch of Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine can’t be used after failing quality standards, officials said Wednesday. The drug giant didn’t say how many doses were lost, and it wasn’t clear how the problem would affect future deliveries.

The culprit: A vaccine ingredient made by Emergent BioSolutions — one of about 10 companies that Johnson & Johnson is using to speed up manufacturing of its recently authorized vaccine — did not meet quality standards. Emergent has been cited repeatedly by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a range of problems, including poorly trained employees, cracked vials and mold at one of its facilities, records show.

The good news: The Baltimore-based factory where the tainted vaccine ingredient was found had not yet been approved by the FDA, and no vaccine in circulation is affected.

J&J had pledged to provide 20 million doses of its vaccine to the U.S. government by the end of March, and 80 million more doses by the end of May. In a statement, the drugmaker said it was still planning to deliver 100 million doses by the end of June and was “aiming to deliver those doses by the end of May.”

President Biden has pledged to have enough vaccines for all U.S. adults by the end of May. The U.S. government has ordered enough two-dose shots from Pfizer and Moderna to vaccinate 200 million people to be delivered by late May, plus the 100 million shots from J&J. A federal official said Wednesday evening that the administration’s goal can be met without additional J&J doses.

On to France, which is battling a new virus surge that many believe was avoidable. In President Emmanuel Macron’s hometown hospital in the medieval northern city of Amiens, COVID-19 patients occupy all the beds in the intensive care ward. Three have died in the last three days. The vast medical complex is turning away critically ill patients from smaller towns nearby for lack of space.

France is now Europe’s latest virus danger zone; Macron has ordered temporary school closures nationwide and new travel restrictions. But he resisted calls for a strict lockdown, instead sticking to his “third way” strategy that seeks to balance protective pandemic restrictions with enough free movement for a restless population.

The French government has refused to admit any failure and blames delayed vaccine deliveries and an unheeding public for surging infections and overwhelmed hospitals. Macron’s critics blame arrogance at the highest levels. They say France’s leaders ignored warning signs and favored political and economic calculations over public health and risk to lives.

“We feel this wave coming very strongly,” said Romain Beal, a blood oxygen specialist at Amiens-Picardie Hospital. “We had families where we had the mother and her son die at the same time in two different ICU rooms here. It’s unbearable.”

Over to India, where every day scavengers plunge their bare hands into garbage freshly dumped at the peak of a New Delhi landfill and start sorting. They are among the estimated 20 million people around the world in both rich and poor nations who, alongside paid sanitation workers, provide an essential service in keeping cities clean. But unlike those municipal workers, they usually are not eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine and are finding it difficult to get the shots.

The pandemic has amplified the risks that these informal workers face. Few have their own protective gear or even clean water to wash their hands, said Chitra Mukherjee of Chintan, a nonprofit environmental research group in New Delhi. “If they are not vaccinated, then the cities will suffer,” Mukherjee said.

Chintan estimates that these unpaid workers save the local government over $50 million and eliminate over 900,000 tons of carbon dioxide per year by diverting waste away from landfills. Still, they are they not considered “essential workers” and thus are ineligible for vaccinations.

Manuwara Begum, 46, lives in a cardboard hut behind a five-star hotel and feels the inequity keenly. She has started an online petition pleading for vaccines and asking, “Are we not human?”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Are there plans to get vaccines to homebound seniors?

Seniors have been among the earliest groups eligible to get vaccinated, and more than 70% of Californians 65 or older have received at least one vaccine dose. Nonetheless, many of those who have yet to roll up their sleeves face major hurdles to vaccination, even though they may be at the highest risk of dying from the virus.

That’s why several grass-roots initiatives have recently sprung up to bring shots to people too vulnerable to leave home, my colleague Lila Seidman reports.

The Glendale Fire Department and Glendale Memorial Hospital have started a pilot program to vaccinate that city’s homebound seniors. USC’s Keck School of Medicine has launched a similar initiative targeting patients throughout L.A. County and beyond. And a team from UCLA Health began vaccinating homebound patients in late January.

Meanwhile, officials appear to be playing catch-up. Last week, the L.A. County Board of Supervisors unanimously voted to direct the county’s Department of Public Health to come up with a strategy to reach homebound Angelenos, with a focus on seniors.

Supervisor Hilda Solis, who spearheaded the initiative, called them “an often silent and forgotten group.” Some 220,000 county residents receive in-home support services, and 55,000 homebound seniors receive daily meals delivered to their homes through Meals on Wheels and similar programs, Solis said. “These represent only a portion of those who are homebound,” she added.

Blue Shield of California, which won a state contract to help with the vaccine rollout, has said that the county’s plan could launch in early April and would include dispatching the Los Angeles Fire Department and other emergency workers to people’s homes.

The initiatives have already made a difference for seniors who otherwise would not have been able to get the much-needed shots.

Take Lillian “Lili” Shaw, who received the COVID-19 vaccine in the dining room of her Glendale home. Frail from advanced age and severe arthritis, among other ailments, Shaw stayed shut in during the pandemic. A caregiver brought her groceries. Friends didn’t or couldn’t visit.

“You mean I can actually go out?” she asked after getting the quick jab. “I’ve been stuck for a year in this prison.”

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Need more vaccine help? Talk to your healthcare provider. Call the state’s COVID-19 hotline at (833) 422-4255. And consult our county-by-county guides to getting vaccinated.

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.