Coronavirus Today: Speaking their language

Good evening. I’m Thuc Nhi Nguyen, and it’s Wednesday, March 10. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

National campaigns to promote COVID-19 vaccines have celebrities, sports stars and the United States’ go-to infectious-disease expert. Their combined star power is supposed to help persuade vaccine skeptics to roll up their sleeves for a shot.

But for some communities, even Dr. Anthony Fauci has nothing on 28-year-old Alba Gonzalez.

Gonzalez is part of CIELO, an Indigenous organization in Los Angeles that is one of many groups showing the power of personal touch when it comes to promoting vaccine awareness, my colleague Leila Miller reports.

L.A. is home to Mexicans who speak languages such as Zapotec, Mixtec and Triqui, as well as Guatemalan Maya who speak languages like K’iche’ and Q’anjob’al. Many speak only basic Spanish and very little English. This language barrier prevents many of them from getting reliable information about vaccines and navigating the appointment system online or by phone.

So Mexican and Guatemalan Indigenous leaders in California are addressing language barriers, accessibility issues and mistrust in government agencies through social media campaigns and good old-fashioned word of mouth.

“It’s bit difficult but not impossible,” said Gonzalez, a Maya from the Guatemalan department of Totonicapán, “because I speak the language and I can give them confidence.”

Outreach takes place in both urban and rural areas. Groups promote COVID-19 vaccines on community radio stations in Santa Barbara and Ventura counties to target Indigenous farmworker families. Advocates in Kern County set up stands outside Mexican markets to distribute gloves, masks and hand sanitizer while speaking to immigrants in their native languages. Volunteers like Isai Pazos, an Indigenous Oaxacan community leader, can call up to 60 families a day.

About 70% of the people Pazos calls have doubts or don’t want the vaccine. He might try teasing them, asking whether they want to be able to gather for Christmas or a quinceañera next year. But he might also tell them about his cousin, aunt and uncle, who died of COVID-19. “Some of the families unfortunately have been misled,” said Pazos, who volunteers with CIELO. “They don’t understand exactly what the vaccine might do.”

With funding from the L.A. County Department of Public Health, CIELO launched its vaccine outreach campaign two weeks ago and has already secured vaccination appointments for more than 140 people. One of them was Cata Ramos Gonazalez, whose husband died of COVID-19 in early January.

“If this deathly sickness wasn’t here, I wouldn’t have lost my husband,” Gonzalez, a Maya immigrant, said in K’iche’. “They didn’t make the vaccine for no reason. It’s something good.”

Gonzalez’s husband sewed garments at home to sell. Without him, Gonzalez depends on families and friends to support her and her children. She has a constant headache from worrying about the future.

With many working low-wage service-sector jobs, Central American Indigenous communities have been particularly vulnerable during the pandemic. As the state tries to address vaccine inequities, groups like CIELO “are the boots on the ground who are the most in tune on how to communicate to specific communities,” said Heather Jue Northover, director of the L.A. County Department of Public Health’s Center for Health Equity.

Part of the reason for the vaccine outreach is to keep lines of communication within the community open for the future.

“Our Indigenous native speakers are a treasure,” said Oscar Marquez, who heads CIELO’s four-person outreach team. “If we can’t keep them alive to help us maintain and pass along not only the language but the customs and the culture, we start to lose ourselves.”

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 6:02 p.m. Wednesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Across California

The L.A. Unified School District is on board. Teachers have signed off. The county could give the green light soon, too. Now it’s up to parents to decide whether their kids will be in Los Angeles Unified classrooms once in-person classes resume.

Even with campus reopenings eminent for the nation’s second-largest school system, opinions are split, my colleague Paloma Esquivel reports.

Katy Meza’s son Matthew is struggling with his virtual third-grade classes, but she questions whether his South Gate school — which often lacked toilet paper and soap before the pandemic — can keep students safe from the coronavirus. On the other hand, Lydia Friend, who lives in Watts, says she’s eager for her two fifth-grade grandsons to return to school because they are suffering from feelings of isolation at home.

Polls conducted by local school districts show that families whose communities have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic tend to be more hesitant about returning to in-person classes. For example, only about 38% of Black families, 30% of Latino families and 29% of Asian American families surveyed by L.A. Unified in November said they’d prefer a return to in-person learning when that option became available, compared with 58% of white families.

The trend is supported by national surveys from the Pew Research Center and USC that found public opinion on school openings varied based on race and income.

One of the few things parents on both sides seem to agree on is that they’ve been left out of the decision-making process. “These are our children,” Meza said. “And they need to work with us to come up with a plan so that we can feel safe.”

The tentative agreement between L.A. Unified and the teachers union announced Tuesday includes plans to reopen campuses for elementary, middle and high school students. The school day would unfold under a hybrid format that allows students to attend some in-person classes and log on for online classes other times. Families still have the option to keep students in distance learning full time.

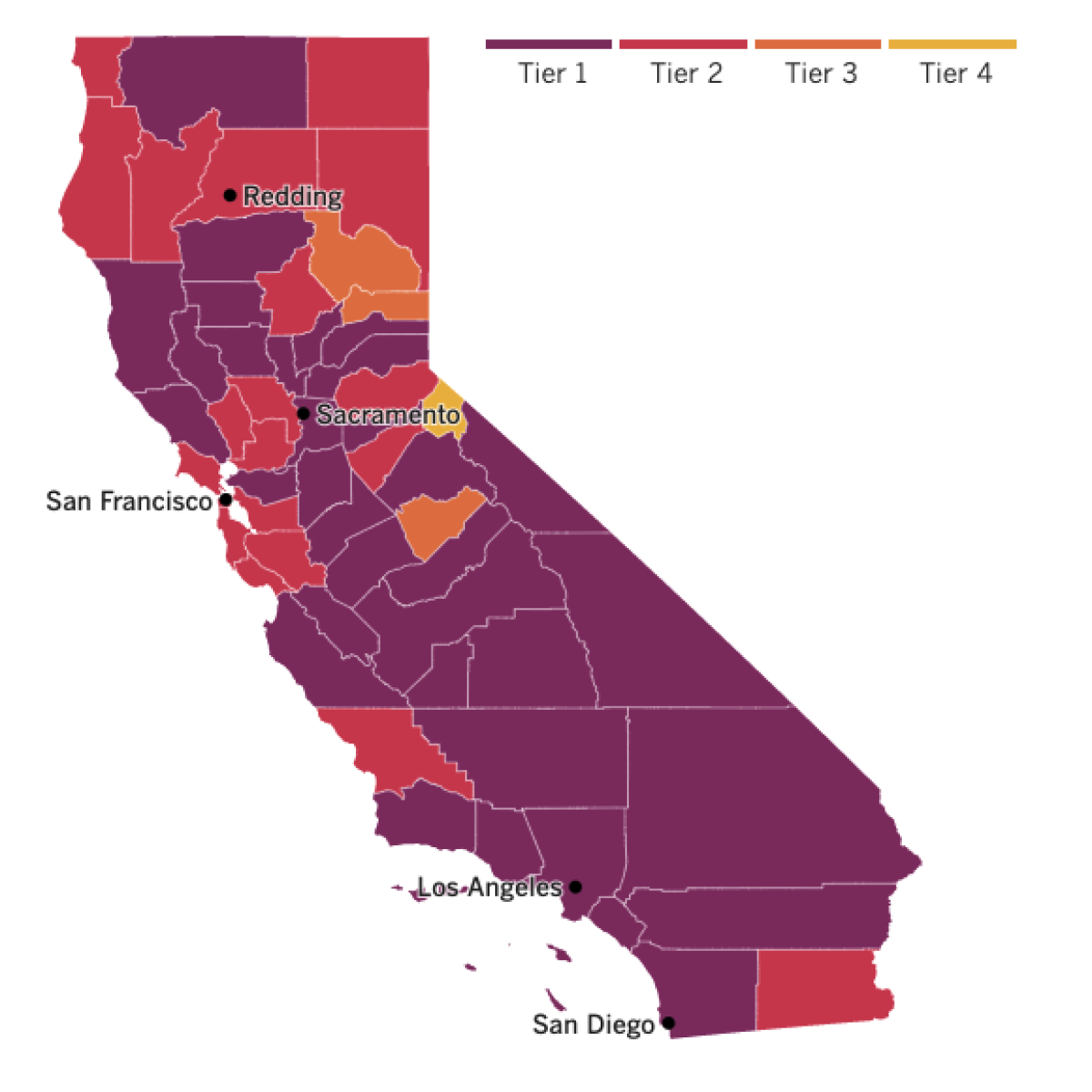

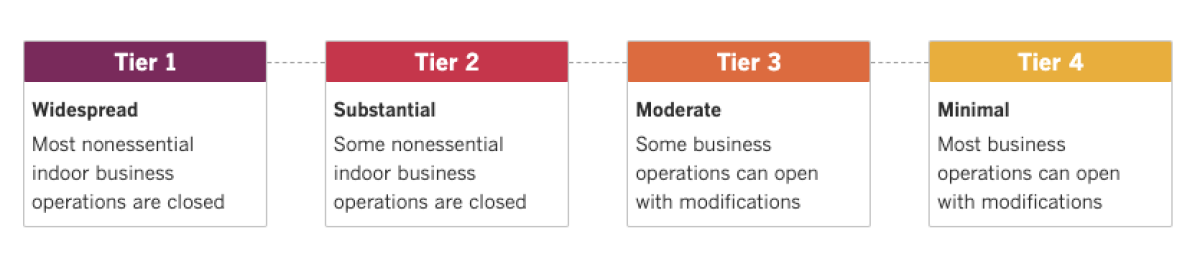

LAUSD elementary schools, which are already allowed to open, could resume by mid-April. Secondary schools could open later in April or in early May, but first L.A. County needs to graduate from the purple tier, which could happen in a matter of days.

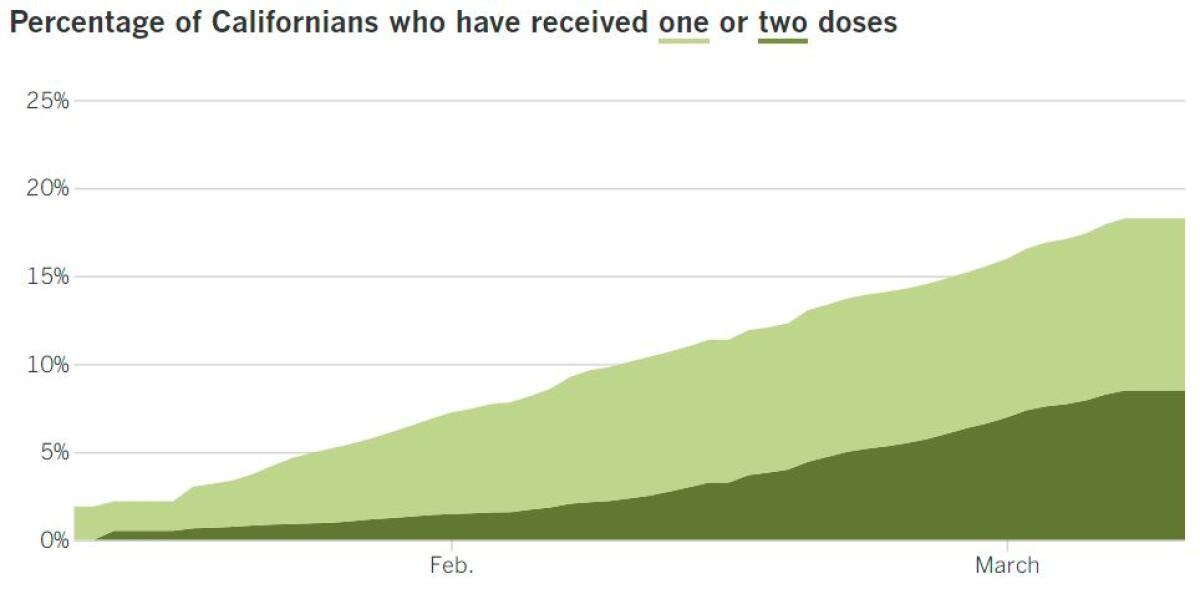

With falling case rates and steadily increasing vaccination numbers, L.A., Orange and San Bernardino counties are all close to reaching the red tier, the second-most restrictive level in California’s four-step strategy for reopening the economy. It could be the beginning of what UCLA forecasters are predicting will be near-record growth for the U.S. and California economies, my colleague Margot Roosevelt reports.

A quarterly economic outlook estimated that the nation’s gross domestic product, which shrank by 3.5% in 2020, will grow 6.3% this year, 4.6% in 2022 and 2.7% in 2023. California could be in even better shape than the rest of the country, as the state was buoyed by high-earning technology and professional sectors that shifted to at-home work during the pandemic. A full recovery in the tourist-dependent leisure and hospitality businesses here will take time.

“This is a very ‘good news’ forecast,” said Leo Feler, senior economist of the forecasting group based at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management. “We have finally turned the corner.”

But the path back won’t be without more complications. The growing number of vaccines administered is paving the way for the economy to reopen, but an expected shortage of shots manufactured by Johnson & Johnson will keep L.A. County’s vaccine supply tight for the rest of the month, my colleagues report.

That’s especially bad timing because people under 65 with disabilities or underlying medical conditions will become eligible for the vaccines starting Monday. The state is still finalizing the final list of conditions that would qualify for priority access, but a bulletin last month said that healthcare providers can use their judgment to vaccinate people ages 16 to 64 who are considered at high risk for severe illness or death from COVID-19 due to health conditions like cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic pulmonary disease, a compromised immune system as a result of an organ transplant, Down syndrome, pregnancy, sickle cell disease, heart conditions, severe obesity or Type 2 diabetes.

L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer suggested that people with underlying conditions contact their doctors to ask about getting the vaccine.

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

President Biden, you’re up.

The House passed a $1.9-trillion COVID-19 economic aid package Wednesday, and it now awaits the president’s signature, which could come as soon as Friday. Your $1,400 stimulus check may be landing within two weeks after Biden signs the bill, my colleague Sarah D. Wire reports.

Along with direct relief checks for individuals making less than $75,000 a year and joint filers who make less than $150,000, the package includes extended unemployment benefits, the biggest-ever expansion of Obamacare and hefty new tax credits to combat child poverty.

Not a single Republican in the House or Senate voted for the package, with many feeling that it was too broad. Indeed, it offers a wide range of relief, including mortgage and rental assistance; targeted aid to the restaurant, child-care and airline industries; funding for COVID-19 vaccines and coronavirus testing; aid to small businesses, schools and tribal governments; and billions of dollars to help state and local governments deal with the economic fallout of COVID-19-related closures. (L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti was “ecstatic” that the stimulus bill will send $1.35 billion directly to the city.)

Many are looking for as much relief as they can get after COVID-19 decimated families both physically and financially. Even months after contracting the disease, symptoms can linger. Some of those experiencing “long COVID” — a pattern of prolonged symptoms following an acute bout of the disease — have had to stop working. And to make matters worse, seeking disability benefits has been a challenge.

Some “long haulers” couldn’t access tests when they came down with COVID-19 early in the pandemic and now lack laboratory confirmation of their disease. Symptoms like fatigue and cognitive impairment are subjective and not clearly linked to the kind of specific organ damage that could strengthen a disability claim.

Sandy Lewis, a pharmaceutical industry researcher, got sick last March and recovered, but she relapsed in April and again in May. She received short-term disability for November and December through her employer-based insurance coverage but was denied an extension. The situation has left her feeling “devastated,” she said, and in serious financial distress.

“This has been such an arduous journey,” Lewis said. “I have no income and I’m sick, and I’m continuing to need medical care. I am now in a position, at 49 years old, that I may have to sell my home during a pandemic and move in with family to stay afloat.”

Scientists are still studying the long-term effects of COVID-19, and lingering questions about the disease and how the pandemic will progress as new variants arise make vaccinations even more urgent. But limited vaccine supply continues to complicate that effort and leaves large groups of essential workers without protection, including farmworkers in many parts of the country.

In states like Texas, New York, Georgia and Florida, farmworkers are not yet eligible for the vaccine, even though health centers that serve agricultural workers are starting to receive doses from the federal government. Farmworkers in California are eligible for the shots and benefit from targeted clinics. But clinics elsewhere have to follow state guidelines and inoculate other workers instead.

The uneven rollout to agricultural workers directly affects everyone in the country. Supermarket prices went up last year when COVID-19 outbreaks shut down meatpacking plants, for instance. “Agricultural workers are important for the security of our food supply,” said Jayson Lusk, a professor of agricultural economics at Purdue. “Making sure we have the people available to plant and harvest will make sure our grocery stores aren’t empty or our food prices don’t rise.”

Biden has said he expects there to be enough COVID-19 vaccine supply for every adult in the United States by the end of May, but he’s not stopping there. The U.S. will buy an additional 100 million doses of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine, bringing its total supply of the single-shot vaccine to 200 million doses.

The federal government expects to get the first 100 million doses by the end of June, with the rest coming in the months following. The additional shots would cover young adults and children, pending results of clinical trials.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: When can children and teens be vaccinated?

Some teens can start marking their calendars for the fall, but they should write with pencil instead of permanent ink, according to the nation’s top infectious-disease expert.

“We project that high school students will very likely be able to be vaccinated by the fall term,” Fauci said Sunday on CBS’ “Face the Nation.” “Maybe not the very first day, but certainly in the early part of the fall for that fall educational term.”

Fauci added that younger children could follow in the first quarter of 2022 since he expects vaccine trials for 5- to 12-year-olds to start around April. It could take a year for results to come in.

No COVID-19 vaccines are currently authorized for use in people younger than 16, but some vaccine makers are already testing their shots in younger teens and even some preteens, my colleague Amina Kahn reports.

Pfizer, which already included 16- and 17-year-olds in its Phase 3 clinical trial, has now fully enrolled its trial for 12- to 15-year-olds. Younger age groups will follow.

The COVID-19 vaccines from Moderna and Johnson & Johnson were tested only in adults and authorized for people 18 and older. Moderna has begun testing its vaccine in minors, while J&J has committed to doing so in the first half of 2021. (So has AstraZeneca, though its vaccine has not yet been authorized for any age group in the U.S.)

Researchers aren’t expecting any big surprises when it comes to the vaccines’ safety and efficacy in children, but the data still need to be gathered in case they’re wrong.

“Sometimes children respond the same to vaccines as adults do but sometimes they don’t,” said Dr. Yvonne Maldonado, a pediatric infectious-disease vaccinologist at Stanford University. “It’s very different for each organism, each type of disease, each vaccine. So there’s no one answer to that question, and that’s why you have to do a trial each time.”

Vaccinating younger people will be a major step toward reaching herd immunity. Children under 18 account for 22% of the U.S. population, and experts estimate that about 70% to 85% of people will need to be immune to the coronavirus to get to the point at which the virus will be unable to find new hosts.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.