Coronavirus Today: Surviving post-COVID medical bills

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Tuesday, Feb. 9. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

We’re learning a lot about the long-term damage the coronavirus can inflict on victims, including breathing problems and chest pain. As the pandemic rages on, another lasting condition has emerged among COVID-19 survivors: overwhelming medical bills that threaten to cripple them financially just as they’re trying to get back on their feet.

Take Patricia Mason, who was rushed to the emergency room by her husband and didn’t see him again for nearly a month. The 51-year-old Vacaville woman was transferred to a different hospital in the middle of the night as her condition deteriorated; two days later, her doctor put her chances of survival at less than a 30%.

Mason did make it through her ordeal last spring, but she did not emerge unscathed, my colleague Maria L. La Ganga reports. She suffers from brain fog, her joints are swollen and painful, and she takes baby aspirin and a handful of supplements every day.

And then there’s the bill for saving her life: $1,339,181.94. Mason and her husband are on the hook for $42,184.20 of that total.

The couple, with five jobs and nine mostly-grown kids between them, knows there’s zero chance of paying it off in full. And they’re not alone.

“The deck is absolutely stacked against the consumer and the patient,” said Sabrina Corlette, co-director of the Center on Health Insurance Reforms at Georgetown University. She added that “getting answers about why certain things are on the bill is almost impossible.”

During the Obama administration, the federal government put a cap on the amount most insurance plans can require patients to pay. But not all plans have so-called out-of-pocket maximums. Even when they do, the annual limit for a family was $16,300 last year. That ceiling rose to $17,100 this year, though insurance companies can adopt a lower limit. Regardless, that kind of money is still hard for many families to spare during the worst recession in nearly a century.

Mason is insured through her husband’s union on a plan administered by Blue Shield of California, but it’s what’s called a self-funded plan that happens to be “grandfathered in” and doesn’t have to abide by federal out-of-pocket maximums. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that 61% of Americans who get their insurance through their jobs are covered by these kinds of self-funded plans, though it’s unclear how many are also exempt from the federal out-of-pocket limit.

Many insurance companies said early in the pandemic that they would waive all out-of-pocket costs for policyholders’ COVID-19 treatment. But most waivers do not include self-funded plans.

A lot of folks could find themselves in the same boat as Mason.

“I don’t have $42,000 to spare,” Mason said. “I am lucky enough to be alive, so we take that into consideration. But the reality is I don’t have [the money]. It’s not going to happen.”

By the numbers

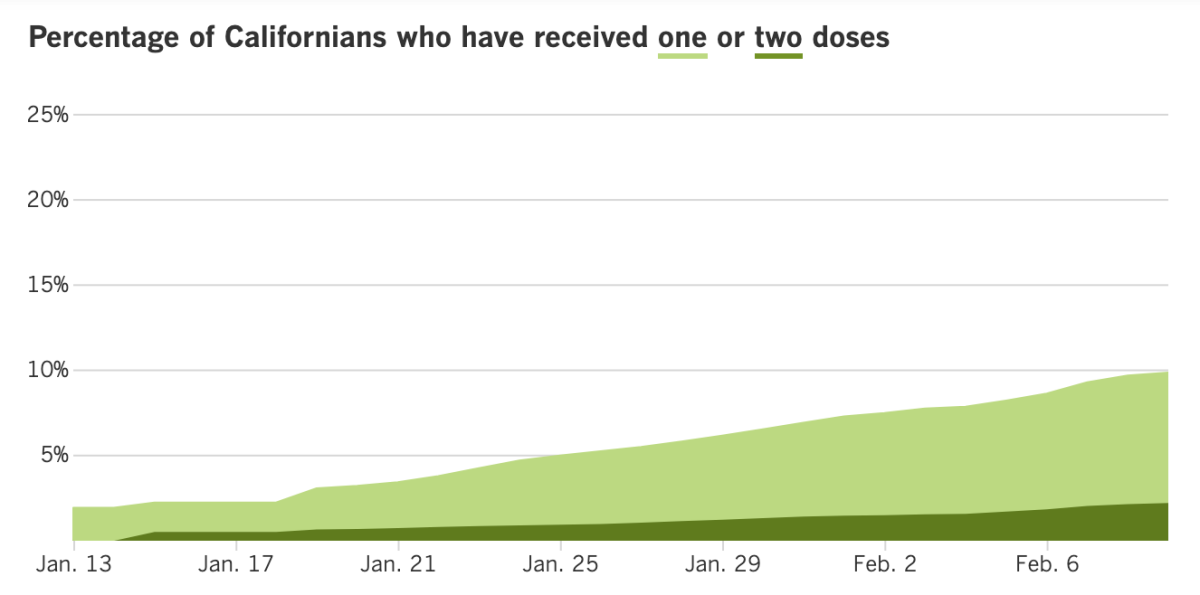

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 6:55 p.m. PST Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Across California

Some bad news for first-time vaccine-seekers in Los Angeles County: Most of the county’s vaccine supply will be needed for second doses into next week. Even stepped-up shipments won’t be enough to break the bottleneck of people needing to complete their inoculation regimen, officials said. County officials have already said they will be limited to administering second doses for the rest of the week at a handful of their major vaccination sites: the Fairplex in Pomona, the Forum in Inglewood, the county Office of Education in Downey, Cal State Northridge, the El Sereno Recreation Center, Six Flags Magic Mountain in Valencia and Balboa Sports Complex in Encino.

And there’s more bad news on the vaccine front: Black, Latino and Native American seniors in Los Angeles County getting COVID-19 shots at a lower rate than white, Asian American and Pacific Islander seniors, new data show. That’s raising new worries about widening equity gaps amid the bumpy vaccine rollout that expanded to the county’s seniors on Jan. 20.

Just 7% of Black residents age 65 and over have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, the lowest percentage of any racial and ethnic group. They’re followed by Native American seniors (about 9%); Latino seniors (14%); white seniors (17%); Asian American seniors (18%) and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander seniors (29%).

“We’re alarmed by the disproportionality we’re seeing in who has received the vaccine,” said L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer, who expressed particular concern about the “glaring inadequacy in the vaccine rollout to date” to Black residents. “This new data shows us that we need to make it much easier for Native American, Black and Latinx residents and workers to be vaccinated in their communities by providers they trust,” Ferrer said, calling it a “top priority” for the public health department.

Ferrer added that the county is committed to opening up more vaccination sites in underserved areas. “We’re going to continue to work with our community partners to ensure that we’re not only getting everyone vaccinated quickly, but we’re addressing the need to provide easier access to neighborhood sites and better access to accurate information about the vaccines,” Ferrer said. The county is also organizing mobile teams to start bringing vaccinations next week to residents of senior housing and to senior centers in the hardest-hit areas.

Long Beach, meanwhile, already has wheels on the ground. My colleague Faith E. Pinho reports that the city used a mobile clinic to vaccinate 500 seniors over the weekend as part of a push to inoculate communities that are particularly susceptible to the coronavirus.

The first mobile clinic, run Saturday by mostly multilingual staff, served predominantly Latino seniors in the Long Beach ZIP Code with the fourth-highest rate of coronavirus infections, city data shows. “It’s important to reach residents from across the city and to get vaccines into lower-income and high-risk communities,” Mayor Robert Garcia said. “We are committed to launching these clinics for seniors and other community members who live in impacted areas.”

Officials around the state are increasingly worried about a coronavirus variant first identified in Britain that’s about 50% more contagious than its predecessors. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have predicted that the U.K. variant, known as B.1.1.7, will become the nation’s dominant coronavirus strain by the end of March. As of Tuesday, there are at least 932 cases in 34 states, with the highest numbers in Florida (343) and California (156). The U.K. variant has been identified in San Diego, Los Angeles, Orange, San Bernardino, Alameda, San Mateo and Yolo counties.

The fourth and fifth cases in L.A. County were confirmed Monday. Ferrer said it’s clear that a fair number of new variants are circulating in the county. “The variants are concerning, because if we let our guard down, the more infectious strains can become dominant,” she said. “And that just makes it a lot easier for this virus to spread.”

The U.K. strain has been cropping up in other parts of California as well: Orange County on Monday confirmed its first case in a resident who reported no international travel history, “which means there are likely more cases in OC,” the Health Care Agency tweeted. It also has made appearances in Yolo County, west of Sacramento. And at least 138 cases have been confirmed in San Diego County, with 50 probable cases there.

A UC San Diego scientist has warned that the U.K. strain is so transmissible that its spread — combined with the rejection of mask use and physical distancing guidelines — could trigger an even worse surge than the one that occurred around the holidays, my colleagues Rong-Gong Lin II and Luke Money report.

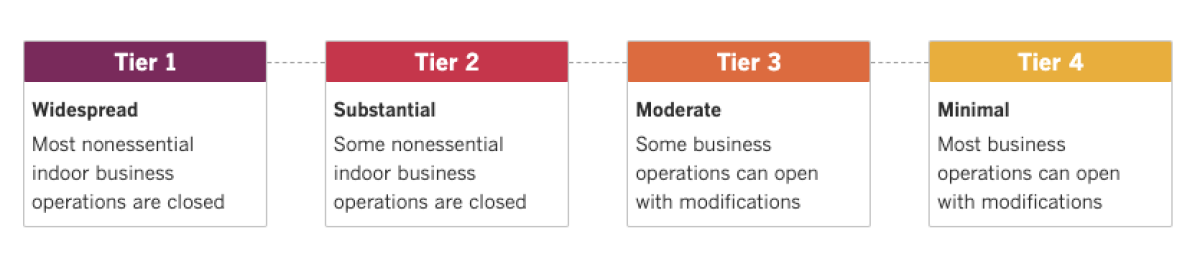

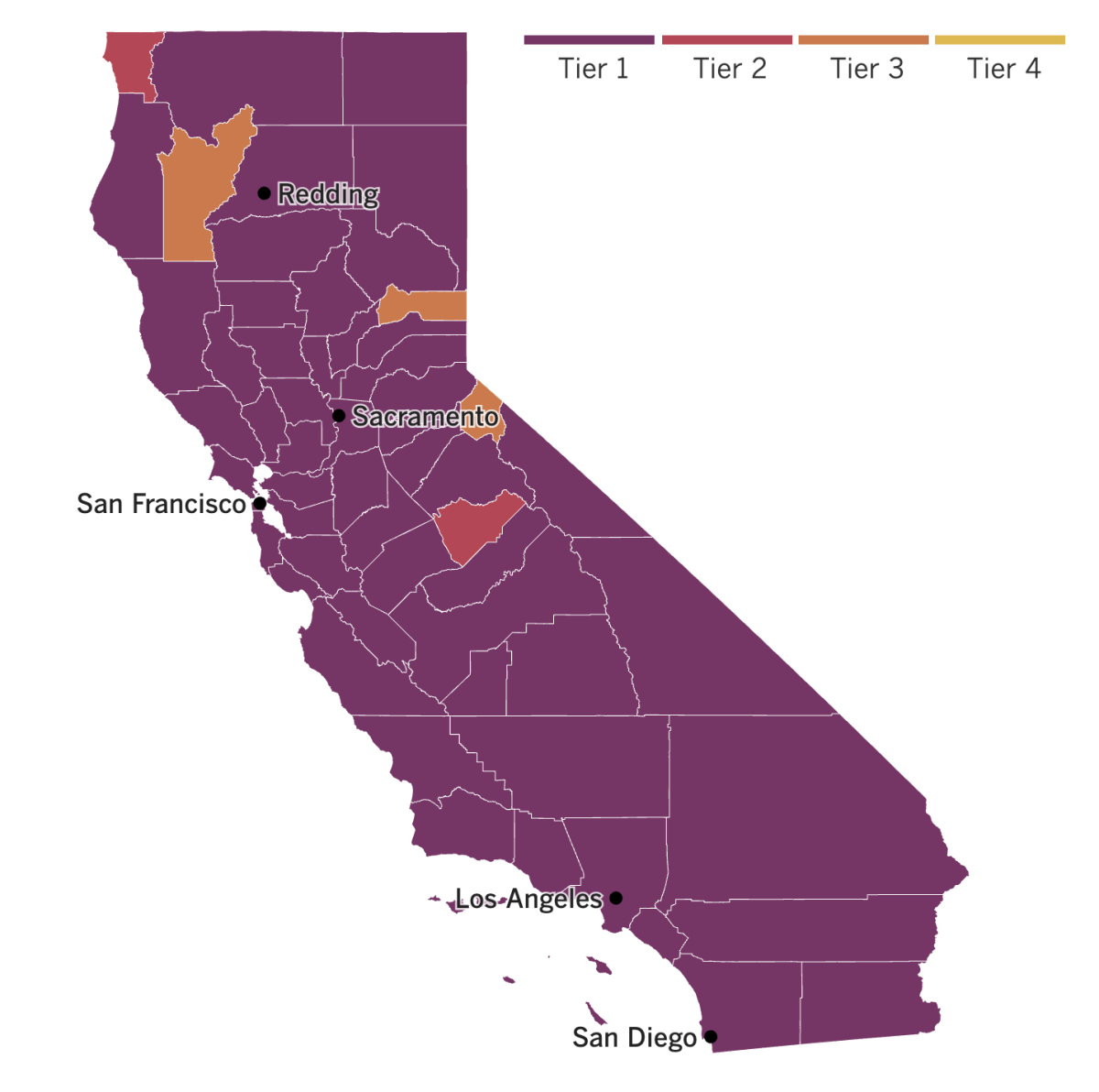

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

For a while, many COVID-19 survivors took comfort in the belief that their bout with the virus afforded them some immunity from reinfection. But there’s growing evidence that having had COVID-19 once doesn’t necessarily protect against getting infected again. New variants can evade the immune system’s hard-won defenses. People can also get second infections with earlier versions of the virus if their bodies mounted a weak defense the first time around, new research suggests.

How long immunity from an infection lasts is one of the big questions of the pandemic. Scientists still think reinfections are fairly rare, but recent developments have raised concerns.

In a vaccine study in South Africa, 2% of people who had already recovered from coronavirus infections became infected again with a new strain. A new variant in Brazil led to several similar cases there. And in the United States, a study found that 10% of Marine recruits who had evidence of prior infection and repeatedly tested negative before starting basic training were later infected again. “Previous infection does not give you a free pass,” said one study leader, Dr. Stuart Sealfon of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. “A substantial risk of reinfection remains.”

Reinfections aren’t just a worry for individual coronavirus survivors; they pose a threat to society at large. That’s because even in cases where reinfection causes no symptoms or just mild ones, people might still spread the virus. And that’s why health officials are urging vaccination as a longer-term solution and encouraging people to wear masks, practice social distancing and wash their hands often.

Even as vaccines continue their rollout, the United States’ testing system remains unable to keep pace with the virus’ spread. Now, some experts are looking to refocus U.S. testing more on mass screening and less on medical precision. They believe this shift could save hundreds of thousands of lives.

The U.S. conducts about 2 million coronavirus tests per day. The vast majority of these are polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, tests, which offer high accuracy because they detect the genetic material but can take days to come back. Rapid tests, on the other hand, look for antigens from a virus particle. Though they’re generally less accurate, they’re good at catching people‘s infections while they’re contagious — and results generally can come back within an hour.

In this case, some experts say, the highly accurate might be the enemy of the good enough. That’s why they’re calling for the easing of regulatory hurdles to make rapid tests easier to use.

Consider North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University: When a Halloween party sparked a COVID-19 outbreak there, school officials used the rapid tests to screen more than 1,000 students in a week. The testing director at the historically Black college said the approach allowed the school to contain the outbreak quickly and keep the campus open. “Within the span of a week, we had crushed the spread,” Dr. Robert Doolittle said. “If we had had to stick with the PCR test, we would have been dead in the water.”

In China, the World Health Organization said Tuesday that the most likely source of the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan was an animal that spread it to another animal, then to humans. WHO officials added that the virus could also have been passed through a frozen product — a possibility that has been widely promoted by the Chinese government, Beijing Bureau Chief Alice Su reports.

As for the theory of a “lab leak” being the origin for the coronavirus outbreak? “Extremely unlikely,” the WHO officials said.

Their comments came after a monthlong visit by a WHO-led team of international experts to Wuhan, where the pandemic-causing virus was first identified in late 2019. The visit was planned as an investigation into the origins of the pandemic, though Chinese authorities have insisted that it was merely a “cooperative exchange.” Either way, it was a tightly controlled trip. The team spent two weeks in hotel quarantine and the other two weeks being shuttled around Wuhan and separated from the general public, while reporters chased behind.

Still, one of the experts said they’d been able to see “every place we asked to see, everyone we wanted to meet.” This included visiting the Huanan Seafood Market (which was suspected as the initial outbreak source) and the Wuhan Institute of Virology (where coronaviruses carried by bats are studied in a high-security lab). The experts said they also met with early COVID-19 patients, reviewed mortality statistics and records of people with flu-like diseases, and discussed the results of nationwide animal sampling and testing with Chinese counterparts.

“Did we change dramatically the picture we had beforehand? I don’t think so,” said Peter Ben Embarek, a WHO expert on food safety and animal diseases. “Did we improve our understanding, did we add details to that story? Absolutely.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: I live in Los Angeles. When are we getting more vaccine shipments?

As we’ve discussed, vaccine doses for first timers will be limited into next week — but for those who want to know when more will be coming, my colleagues Luke Money, Rong-Gong Lin II and Colleen Shalby have some answers.

Los Angeles County has seen its vaccine shipments zigzag over the past month, presenting a challenge for officials trying to accurately predict the amount of supplies they’ll have. For example: About 193,950 doses arrived the week of Jan. 11, but 168,575 came the following week and even fewer — only 137,725 — were delivered the week after that.

Hopefully, those numbers are now on the upswing: The county received 184,625 doses last week — a number expected to climb this week to more than 218,000.

L.A. isn’t the only county forced to parcel out far fewer vaccines than it needs. Officials throughout California have lamented the limited and variable vaccine shipments they’ve received, saying they have the capability to administer significantly more shots.

“We can’t move fast enough,” Gov. Gavin Newsom said. “We are sober and mindful of the scarcity that is the number of available vaccines.” Officials say they will be able to provide more first doses when they start getting larger, more sustainable shipments. In the meantime, they’re prioritizing the currently available vaccine for folks who need their second doses.

There has been considerable discussion about whether officials should shift their focus to giving first doses to as many people as possible and not worrying so much about the second doses for now. The thinking goes that even one shot provides some level of protection against COVID-19.

For what it’s worth, the CDC has said if it’s not feasible to give the second doses on time — three weeks after the first shot in the case of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and four weeks later with the Moderna one — then in extremely rare circumstances, administering the second dose within six weeks is acceptable.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the U.S. government’s top infectious diseases expert, said the two-dose regimen unlocks the full benefits of the vaccine. While the first dose provides “some degree of protection,” the second dose multiplies the level of protection by a factor of 10.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.