Coronavirus Today: The outdoor dining ban worked

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Monday, Feb. 1. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

As coronavirus case numbers fall and California’s restaurants dust off their patios and set up sidewalk seating, it’s worth taking a look back at the latest stay-at-home order to ask: Did the ban on outdoor dining make a difference?

The ban became a political flashpoint this fall and winter, as restaurants hanging on by a thread lost a desperately needed lifeline, and a pandemic-weary public lost its patience with confusing regulations that allowed indoor malls to remain open, while outdoor restaurant operations had to close.

Experts now think they have an answer. They say there’s mounting evidence that Gov. Gavin Newson’s stay-at-home order, including the outdoor dining ban, did help turn the deadly surge around, my colleagues Soumya Karlamangla and Rong-Gong Lin II report.

After the deadliest surge of the pandemic, declines in new infections and hospitalizations can be traced to the changes that Californians started to make a full two months ago, experts say.

If this conclusion feels confusing, I get it. The pandemic may mess with your gut sense of how things are going, because we don’t see the rewards of our good behavior — or the consequences of our bad behavior — until weeks or months later. But they do matter.

In early December, Californians reduced their movements around their communities to a rate that was 40% lower than typical — the lowest level since May. That was due to a mix of Newsom’s orders plus a natural reaction to the alarming case numbers and rhetoric from officials, said Ali Mokdad, an epidemiologist at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington.

Consider Los Angeles County, where the stay-at-home order and outdoor dining ban were followed by a drop in the coronavirus transmission rate from 1.2 before the restrictions took effect in late November to 0.85 by early January. (Anything above 1.0 means an outbreak will grow exponentially.) That drop signaled that the county started turning things around within about two weeks — though it wasn’t apparent until a month later, due to the many weeks of lag time between new infections and hospitalizations.

“You did the right thing at the right time,” Mokdad told my colleagues. “The winter is working against all of us, but at least you preempted a much bigger surge of cases by doing what you did.”

California officials estimated that the state’s order — which forbade nonessential travel, banned outdoor social gatherings and shuttered nail and hair salons, museums and outdoor dining — kept as many as 25,000 people from being severely sickened and hospitalized with COVID-19.

Scientists say they can’t tease out which part of the order was most effective in turning the tide, but several public health experts told my colleagues that the outdoor dining ban likely played a crucial role. There are a few key reasons:

- It signaled to the public that the coronavirus crisis was worsening.

- It eliminated a known risk. The virus can spread outdoors — recall the White House Rose Garden ceremony that became a super-spreader event — especially when people aren’t wearing masks. Not only do diners remove their masks to eat, they are often seated less than six feet apart and typically spend far more than 15 minutes together — conditions that violate three fundamental tenets of COVID-19 risk reduction.

- Outdoor dining became even riskier simply because of the astronomically high rates of contagion during the worst part of the surge. That meant Californians were more likely to be exposed to the virus during what would have previously been thought of as low-risk activities.

- The safety benefits of dining outdoors were undermined to some extent by restaurants that put up plastic sheeting to protect diners from winter winds — winds that could have kept viral particles away from other diners and employees.

So even though critics complained that there weren’t enough data to support the ban on outdoor dining, and even though it faced political pushback and triggered lawsuits, experts say it was better to act than to risk more deaths.

“I think we need a little leeway in trying to protect the public from a disease that’s killed more people in 10 months than we lost in all of World War II,” said UC San Francisco epidemiologist Dr. George Rutherford.

By the numbers

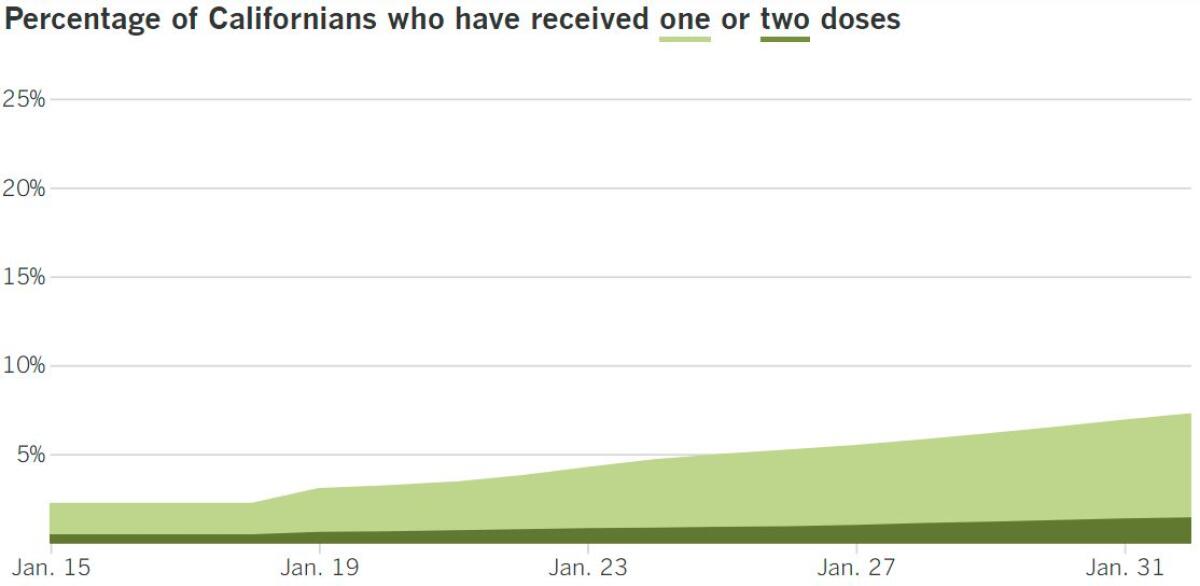

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 3:33 p.m. PST Monday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Across California

Before we celebrate the relative success of the stay-at-home order, let’s pause to consider the magnitude of what we’ve just been though.

January was the deadliest month of the pandemic in Los Angeles County, a Times data analysis shows. In the first month of 2021, 6,411 people succumbed to COVID-19 in the county — more than twice the number who died in December, the previous deadliest month, with 2,703. The cumulative death toll is nearly 17,000.

The suffering in Los Angeles echoes the tragic trend across the state: California also reported a record number of deaths in January, with 14,940. That brought the statewide death toll to just under 41,000, a threshold that was crossed Monday.

It can be hard to get our heads around numbers like these, but think of it like this: Those 41,000 deaths mean that at least 1 in every 1,000 Californians has been killed by COVID-19.

The numbers are similarly grim countrywide: More than 95,000 people in the U.S. died from COVID-19 last month, dwarfing the previous high of just over 77,000 deaths in December. Altogether, more than 441,000 people have died nationwide since the first cases of COVID-19 were reported just over a year ago. L.A. County has seen more COVID-19 deaths than any other county in the country. (Chicago’s Cook County is a distant second, with 9,420 deaths.) It’s a stark reminder that while the situation is turning around, residents and businesses need to remain vigilant.

“Because some sectors have reopened, it doesn’t mean that the risk for community transmission has gone away,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said. “It hasn’t, and each of us needs to make very careful choices about what we do and how we do it. This virus is strong, and we are now concerned about variants and what these will mean in our region.”

There are plenty of reasons to stay on guard. Among them: A more contagious coronavirus variant from the United Kingdom is sparking worry about a future surge in South California. It’s possible that hospital systems could be overwhelmed again if the U.K. variant, which is growing in case numbers in the Southland, spirals out of control. It has already been identified in 32 states, with Florida’s count of at least 147 cases topping the list, and California’s not far behind, with at least 113.

The U.K. variant, also known as B.1.1.7, is expected to become dominant in the Southland within a matter of weeks. L.A. County officials announced Saturday a second confirmed case and said the variant was “spreading in the county.” At least two cases have been identified in San Bernardino County. San Diego County has the state’s largest cluster of known cases of B.1.1.7 — at least 109 confirmed cases and 44 additional cases linked to them. All of this is worrying because this particular variant is thought to be 50% more transmissible than the standard variety — and there’s recent evidence that it may be more virulent as well.

“I can’t stress this enough — with the emergence of B.1.1.7 and other strains which may be more transmissible and potentially more lethal — now is the time to double down on reducing transmission and expanding vaccination,” said Natasha Martin, associate professor in the UC San Diego Division of Infectious Diseases and Global Health.

San Diego is taking the U.K. variant seriously, placing a curfew on outdoor dining between 10 p.m. and 5 a.m. Los Angeles County officials have not restricted late-night dining hours, though they have banned TV viewing at restaurants so that exuberant sports fans don’t spread the virus by yelling and screaming while they eat. “We really do need to be cautious as we move forward,” especially with the Super Bowl coming up, said L.A. County Health Officer Dr. Muntu Davis. “There is no such thing as no risk at a restaurant or any other setting where people from different households are together.”

The TV ban is one of several new regulations on county eateries: Under new rules, outdoor dining and wine service seating must be limited to 50% capacity, with tables positioned at least eight feet apart. Outdoor seating also must be limited to no more than six people per table — and everyone sitting together must be from the same household.

If conditions improve, Davis said, the county will consider changing its rules. “Right now, we have to ease into these reopenings,” he said. “We want to see these cases continue to come down, our hospitalizations continue to come down. Our healthcare workers have been doing a great job ... they are tired.”

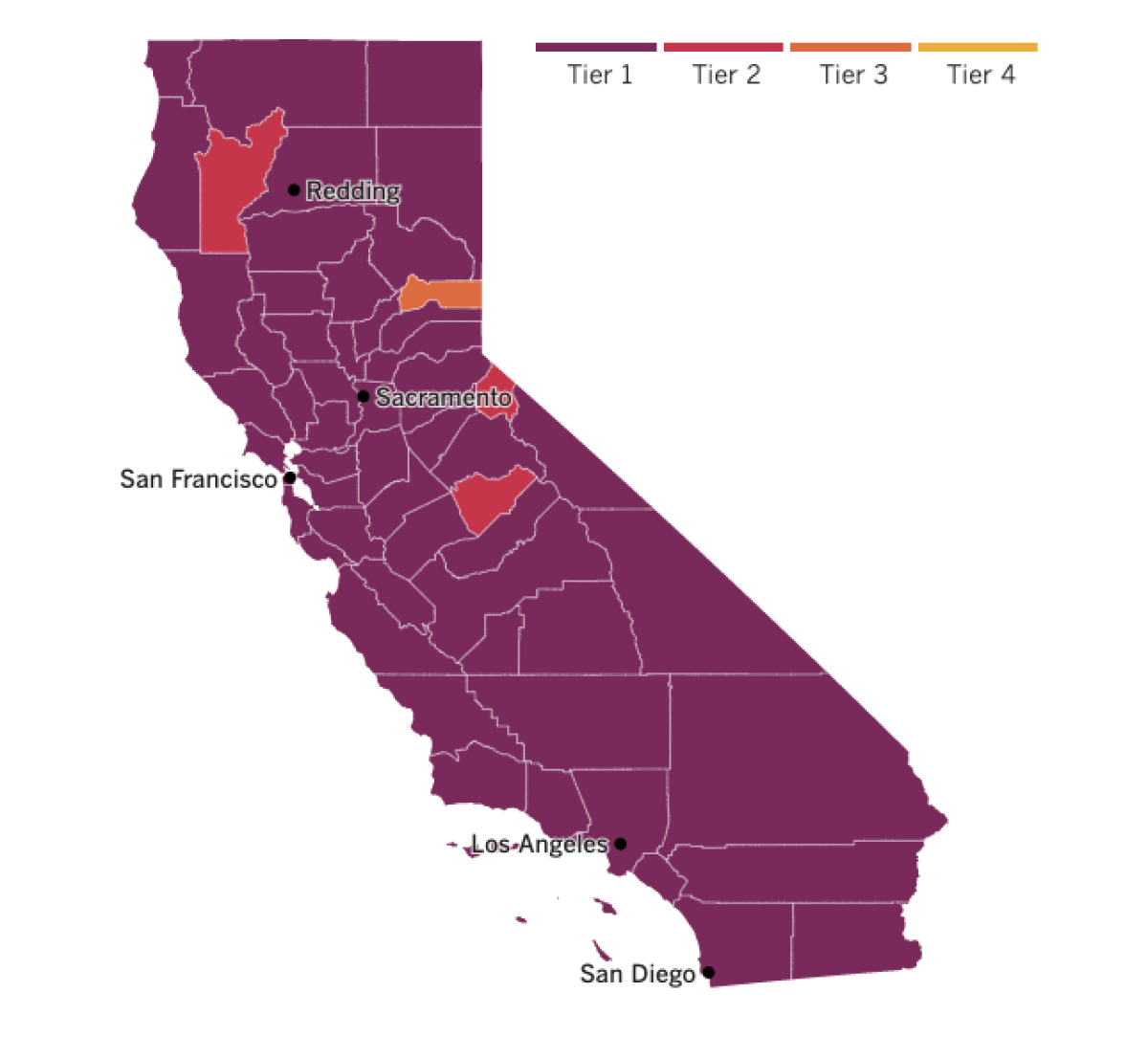

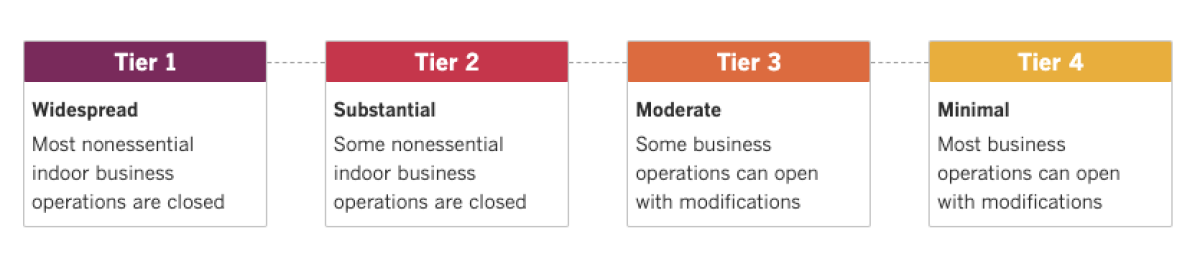

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

In Washington, President Biden met with 10 Republican senators Monday to test the waters of bipartisanship on coronavirus relief. Meanwhile, Democrats on Capitol Hill took the first step toward fast-tracking the White House’s $1.9-trillion proposal through a legislative procedure that wouldn’t require GOP backing, my colleague Eli Stokols writes. Although Biden’s first meeting with lawmakers appeared cordial, it may amount to a token demonstration by both sides — a chance to listen to the other side rather than a negotiation meant to bridge the gulf between them.

The group of 10 moderate GOP lawmakers set out its counterproposal Sunday, with a $618-billion measure that would include more limited direct relief targeted to the neediest individuals, an extension of unemployment benefits through June (three months shorter than under Biden’s plan) and funding for vaccine distribution, school reopenings and small business loans — albeit in smaller amounts than Biden had proposed.

The group’s leader, Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine), expressed appreciation after leaving the Oval Office that Biden “chose to spend so much time with us.” She called the meeting “excellent” and declined to offer details or criticism even as she acknowledged the impasse. “I wouldn’t say we came together on a package tonight. No one expected that, but what we did agree to do is to follow up and talk further,” Collins said.

While Biden has vowed to restore a greater degree of bipartisanship in Washington, he has argued recently that the GOP’s scaled-down proposal — one-third the size of the administration’s package — would be grossly inadequate. He appeared determined to push ahead with his plan, which would deliver more relief to more Americans. Unlike the Republican plan, it includes funding for state and local governments and an increase of the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour.

Now to Alabama, where the COVID-19 vaccination effort is off to a shaky start in Tuskegee and other parts of Macon County. Area leaders say the resistance among residents was spurred by a distrust of government promises and decades of failed health programs. It’s also where many folks have relatives who were subjected to unethical government experimentation in the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study, in which the government unethically used unsuspecting Black men as guinea pigs to study the sexually transmitted disease.

Take Lucenia Dunn, the town’s former mayor. Even though she spent the early days of the pandemic encouraging residents to wear masks and keep a safe distance from one another, Dunn is wary of getting vaccinated. “I’m not doing this vaccine right now. That doesn’t mean I’m never going to do it. But I know enough to withhold getting it until we see all that is involved,” Dunn said.

The Rev. John Curry Jr. said he and his wife got their shots after the health department said they could get appointments without a long wait. Curry, pastor of the oldest Black church in town, said he is encouraging congregants to get vaccinated — but he also said he understands the lingering distrust in a town that will forever be linked to one of the most reviled episodes in U.S. public health history. “It’s a blemish on Tuskegee,” he said. “It hangs on the minds of people.”

And now, across the pond for some somber news: The 100-year-old British man who raised $45 million to fight COVID-19 is hospitalized with the disease. Tom Moore, a World War II veteran, became an emblem of hope in the early weeks of the pandemic last April when he walked 100 laps around his garden in England as a fundraiser for the National Health Service, to coincide with his 100th birthday. He met his goal of 1,000 pounds ($1,370) and then some, raising about 33 million pounds ($45 million) in the effort. Moore, who rose to the rank of captain while serving in India and what is now Myanmar during the war, was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in July for his efforts.

Moore’s daughter said Sunday that her father, widely known as Capt. Tom, had been admitted to Bedford Hospital because he needed “additional help” with his breathing. Her father had been treated for pneumonia for a few weeks before he tested positive for the coronavirus last week, she said, adding that he was being cared for in a regular hospital ward, not in an intensive care unit.

Well wishes have poured in, including from British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who said in a tweet that Moore had “inspired the whole nation, and I know we are all wishing you a full recovery.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: I’m pregnant. Should I get the COVID-19 vaccine or avoid it?

As with many decisions involving the pandemic, there are no easy answers to this question, my colleague Karen Kaplan writes. The Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines that federal regulators have authorized for emergency use in the U.S. have not been tested for safety or efficacy in pregnant women, so there are no hard data on the subject.

That said, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says the vaccines “should not be withheld from pregnant individuals who meet criteria for vaccination” — but the doctor group also says that “pregnant patients who decline vaccination should be supported in their decision.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention strikes a similarly neutral tone, saying that if pregnant women are eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine, “they may choose to be vaccinated,” but stops short of saying that they should.

Both the CDC and ACOG suggest that pregnant women weigh the benefits of a vaccine against the possible risks, noting that the pros and cons may be different for each person. A consultation with a doctor may help but shouldn’t be required, both say.

Kaplan lays out in detail what we know and what we don’t — if you’re thinking about this, you should read the full story. But I’ll sum up a few points here:

- Vaccines are routinely given to pregnant women to protect them and their developing babies from diseases like influenza and whooping cough.

- A handful of pregnant women unintentionally made it into the Pfizer and Moderna clinical trials, but there were too few to draw any conclusions about vaccine safety, federal scientists concluded. The limited data had yet to reveal any red flags, as none of the pregnant women in the trials who got the real vaccine had any pregnancy-related problems.

- Though the risk of developing severe COVID-19 is low for any woman of childbearing age, studies suggest that a pregnant COVID-19 patient is more likely than her non-pregnant peers to be admitted to a hospital’s intensive care unit, more likely to require breathing assistance from a mechanical ventilator and more likely to die of the disease.

- Pregnant women with COVID-19 may also be at increased risk of delivering their babies prematurely or requiring a cesarean section.

- There’s no biological reason to worry about either vaccine making a pregnant woman sick, ACOG says. Neither vaccine is made with actual coronavirus, so there’s no chance that it will cause an infection.

Data are even more scant when it comes to new mothers who are breastfeeding, though Kaplan points out that few if any vaccines are considered unsafe for nursing mothers. The CDC advises nursing mothers who want to get vaccinated to go ahead and do so, and ACOG agrees they should be eligible. The benefits of immunization are real, and they’re not outweighed by any “theoretical concerns” about vaccine risks, the group says.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask. Here’s how to do it right.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.