Coronavirus Today: Vaccine inequities emerge

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Wednesday, Jan. 27. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

One of the inescapable patterns of the pandemic has been how the virus does not touch all lives equally: Along with the elderly and those with underlying health conditions, people who are Black, Latino or poor have experienced a disproportionate number of serious illnesses and deaths. That’s a big reason why state officials want to ensure that all residents have equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines.

But just weeks into California’s bumpy vaccine rollout, there’s mounting evidence of inequities in the Southland when it comes to who’s getting the shots — and it’s prompting calls to refocus on the state’s vulnerable communities.

L.A. County officials said they’re worried about the low vaccination numbers among healthcare workers in South L.A. and other communities of color. And advocates are expressing concern that the state’s new vaccine priority plan will force essential workers to wait longer for their vaccines in spite of the dangers that are an integral part of their jobs. Keep in mind, Black and Latino people are overrepresented among many essential workers who face a higher exposure risk because they don’t have the option of working from home.

The county’s Department of Public Health released demographic data this week showing a markedly lower vaccination rate for county health workers who live in South L.A. compared with other regions that aren’t home to large Black and Latino communities. Slightly fewer than one-third of the county’s roughly 4,000 Black healthcare workers have been vaccinated for COVID-19 — a far lower percentage than for any other racial or ethnic group. More than half of the county’s Black healthcare workers haven’t even requested their shots, the county’s data show.

In response, the county will open six new vaccination sites in the overlooked area, including one at Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital’s outpatient center and one at St. John’s Well Child & Family Center.

“There may be many issues that contribute to the lower vaccination rates that we’re seeing in some communities, but the one issue that we don’t want to have accounting for a lower vaccination rate is that there wasn’t good access to places for people to get vaccinated,” Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said.

Vaccine hesitancy almost certainly plays a role: Just 32% of Black adults nationwide said in a Pew Research Center survey in September that they would definitely or probably take a COVID-19 vaccine. That compared with 52% of white adults, 56% of Latinos and 72% of Asian Americans. “We have a long history in this country and other countries that make it difficult for people to trust some of the medical advances that we’re promoting,” Ferrer said.

County Supervisor Hilda Solis also called out the low vaccination rate for Black healthcare workers and said the rates among Native American and Latino residents were also far too low. “I know there’s large numbers of other populations that are getting the vaccine at higher rates than others, and I would just ask: What are we going to do?” Solis said.

State officials insist that fairness remains a key consideration as the vaccine is rolled out to groups beyond healthcare workers.

“It’s an important equity principle to get those who are disproportionately impacted vaccine [doses] quickly,” said Dr. Mark Ghaly, California’s health and human services secretary. Part of that equation is to allocate vaccines in a way that ensures access for “low-income neighborhoods and communities of color.” To that end, he added, “providers will be compensated in part by how well they are able to reach underserved communities.”

That would seem to be at odds with Gov. Gavin Newsom’s new plan to prioritize vaccines for people based on their age. Hundreds of thousands of low-wage workers and people who are incarcerated or homeless will have to wait longer for their shots, leaving them vulnerable to the deadly virus, said Najee Ali, a South L.A. activist. “It’s a life-or-death situation for Black and Latino essential workers,” he said.

County Supervisor Holly Mitchell noted that Latino residents of L.A. County are dying of COVID-19 at triple the rate of white residents, and that the COVID-19 death rate for people in the county’s most impoverished neighborhoods is almost four times the rate for residents of the wealthiest areas.

“If our ultimate goal is to reduce infections, hospitalization and mortality rates, we’ve got to figure out how to target those who are truly at most risk,” Mitchell said.

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 6:24 p.m. PST Wednesday:

Track the latest numbers and how they break down in California with our graphics.

Across California

Major news for the vaccine rollout: Advisors to Newsom have struck a far-reaching agreement with Blue Shield of California that calls on the health insurance company to oversee the distribution of vaccine to counties, pharmacies and private healthcare providers. The contract is expected to be finalized soon, and the transition in oversight will take several weeks, a spokesman for the California Department of Public Health said Wednesday.

The move is a stark departure from the more decentralized process that has been criticized for providing inconsistent access across different parts of the state, my colleagues Melody Gutierrez and John Myers write. Tasks that until now have been overseen by state and local government officials will be outsourced to the company.

“We understand that vaccine supply is limited,” said state Government Operations Secretary Yolanda Richardson. “But we also need to address that the supply we have now needs to get administered as quickly as possible, so we’re developing an approach that allows us to just that.”

Blue Shield’s employees will be tasked with managing the flow of vaccination requests and deliveries using new state guidelines that determine the order in which Californians will be eligible for the shots. Those guidelines are expected to abandon some of the state’s more detailed categories of eligibility by employment. Instead, they’ll use a not-yet-explained approach based largely on age. State officials said the new system, with Blue Shield at the helm, will bring equity to a COVID-19 vaccine distribution process that has thus far been dictated by where Californians live.

Santa Clara County has brought the hammer down on Good Samaritan Hospital in San Jose after the healthcare facility offered COVID-19 vaccines to teachers from a nearby school district even though they were not in the priority group for the shots.

Until the hospital provides “sufficient assurances” that it will follow state and county guidelines — and offers a concrete plan for doing so — the medical center will not receive any more shots, the county’s testing and vaccine officer said in a letter. There is an exception: The hospital will get enough doses to give second shots to people who have already had their first dose.

The trouble began after the hospital offered teachers a chance to jump the vaccination line, which currently prioritizes healthcare workers and people 75 and older. The offer was relayed to district employees in an email from the superintendent of the Los Gatos Union School District, who called it “a wonderful gesture by our Good Sam neighbors.”

The school district raised money last year to provide meals for front-line workers at Good Samaritan and another hospital.

Santa Clara County Counsel James R. Williams called the offer “very concerning” for several reasons. Among them: The hospital seemed to be “reaching out to a specific district” based on the appearance of “meals provided,” rather than to all school districts, Williams said. Also, Good Samaritan appeared to be “affirmatively suggesting” that school district employees commit perjury by “registering themselves as if they were healthcare workers,” Williams said.

Here’s a little bit of good news: The gorillas at San Diego Zoo Safari Park who had taken ill with COVID-19 are now close to a full recovery, officials say. The troop of eight had been sick for weeks after they were exposed to the coronavirus, probably by a keeper who tested positive for an infection in early January.

Days after that presumed exposure, a few gorillas began coughing, and most members of the troop seemed a little less energetic than usual, park executive director Lisa Peterson said. Park staff sampled and tested the troop’s poop to confirm the diagnosis. The gorillas had been sickened by a fast-spreading, homegrown strain that has been connected to at least 14 COVID-19 cases in San Diego County and 446 infections statewide.

The Safari Park team kept a close eye on troop leader Winston, a 49-year-old silverback who had pneumonia (probably due to COVID-19) as well as heart disease, an underlying medical condition that has been linked to more severe COVID-19 illnesses in humans. Winston received antibiotics, heart medication and an antibody treatment and has been much more active since receiving the antibodies, officials said.

Now all of the troop members seem to be on the mend. “We’re not seeing any of that lethargy. No coughing, no runny noses anymore,” Peterson said. “It feels to us like we’ve turned the corner.”

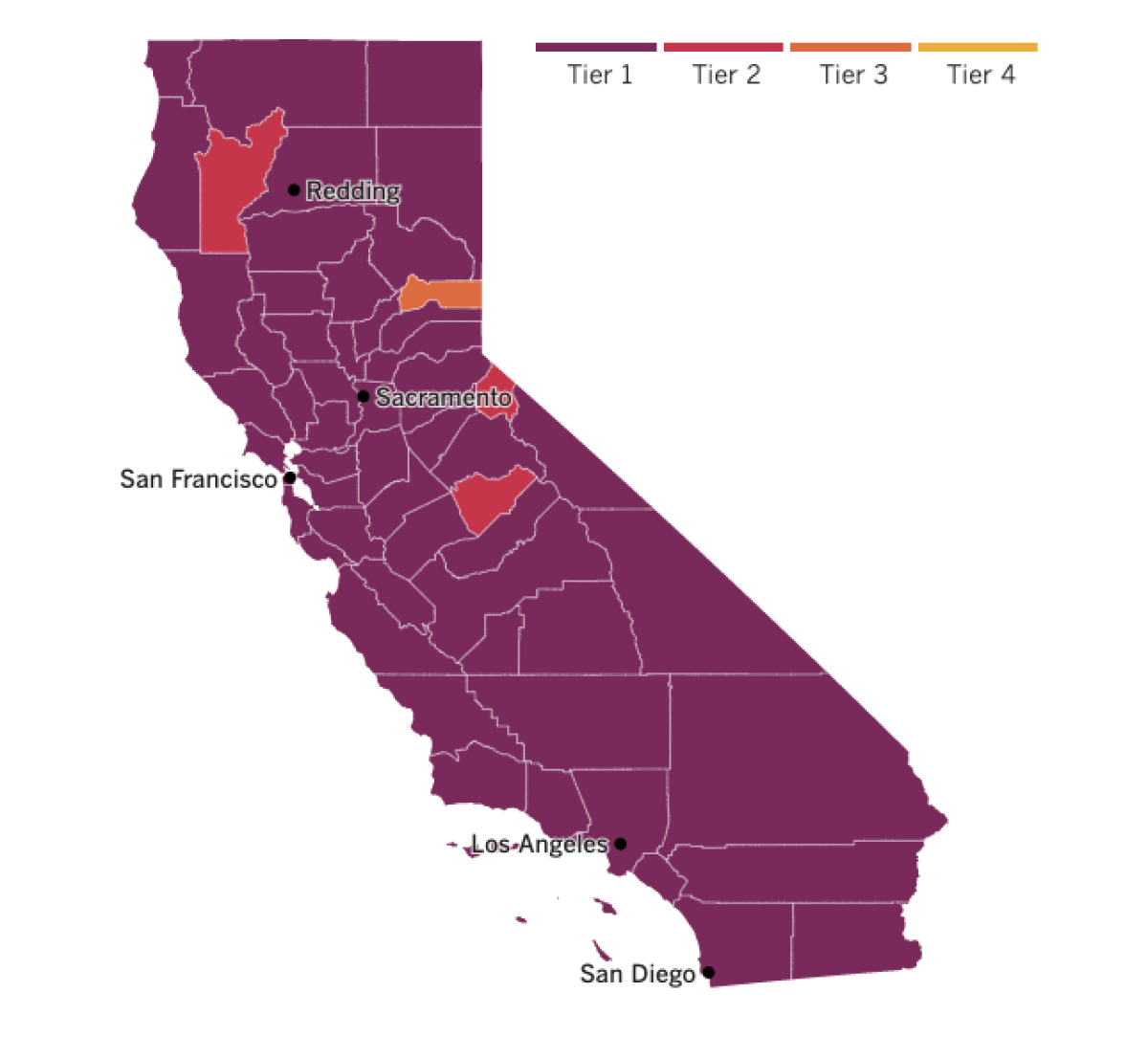

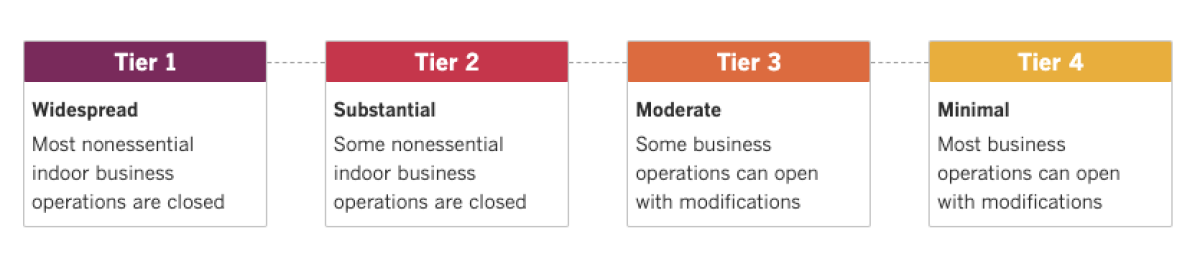

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

The airline industry has been battered by a calamitous decline in business as the pandemic grounded flights and eviscerated air travel. Now an industry group is calling on the World Health Organization to rule that it’s safe for people to fly without needing to quarantine once they’ve received a coronavirus vaccine. Such guidance is essential to the industry’s efforts to get people moving once infection rates slow down, the International Air Transport Assn. said Wednesday.

The IATA is looking to develop a digital travel pass that would make use of vaccine certificates and a proposed Travel Pass smartphone app, said Nick Careen, IATA’s senior vice president for passenger matters. (The app can also be used to store a negative test result.) The trade group would like to develop common standards for the vaccine certificates, and that work needs to move along much faster because the app is due to launch in March, Careen said.

“We have been suggesting this for months,” he said. “The WHO needs a fire lit underneath it to get this done sooner rather than later. Even then, there’s no guarantee that every government will adopt the standard right away.”

But WHO’s Emergency Committee on COVID-19 doesn’t recommend that countries demand proof of vaccination from incoming travelers for a reason: Vaccines are effective against the disease known as COVID-19, but it’s not yet known whether they actually reduce coronavirus transmission. So theoretically, a person who is vaccinated could still be exposed to the virus and, while experiencing no symptoms, inadvertently transmit it to someone without protection.

WHO said it would rather see nations implement coordinated and evidence-based measures for safe travel.

Pharmaceutical giant Merck said it is giving up on two potential COVID-19 vaccines following poor results in early-stage studies. Although the potential vaccines were well tolerated by patients, they generated a subpar immune system response compared with other vaccines.

The drugmaker will instead focus on studying two possible treatments for COVID-19. The federal government is paying Merck about $356 million to fast-track production of one of its potential treatments, a therapy called MK-7110 that has the potential to minimize the damaging effects of an overactive immune response to COVID-19. The funds will allow the company to deliver up to 100,000 doses by June 30 if the Food and Drug Administration authorizes the treatment for emergency use.

In Austria and Slovakia, hundreds of Holocaust survivors were set to get their first COVID-19 vaccinations today as a way to mark International Holocaust Remembrance Day. The move was an acknowledgement of their past suffering 76 years after the liberation of the Auschwitz death camp, where Nazis killed more than 1 million Jews and other people. In all, more than 6 million European Jews were killed during the Nazi’s Third Reich.

“We owe this to them,” said Erika Jakubovits of the Jewish Community of Vienna, which organized the vaccination drive. “They have suffered so much trauma and have felt even more insecure during this pandemic.”

More than 400 Austrian Holocaust survivors, most in their 80s or 90s, were expected to get their first shots at Vienna’s convention center. In many ways, the world’s approximately 240,000 Holocaust survivors fit the definition of a population vulnerable to the pandemic and in urgent need of inoculation. In addition to being elderly, many suffer medical problems today because they were deprived of proper nutrition when they were young. On top of that, many live isolated lives and are still suffering psychological stress as a result of losing everything in their lives to Nazi persecution.

“We have a duty to survivors to ensure that they are able to live their last years in dignity, without fear and in the company of their loved ones,” said Moshe Kantor, head of the European Jewish Congress.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Can I get my second dose of COVID-19 vaccine a few days early?

Yesterday, we talked about whether it’s OK to get your second shot later than the recommended interval of 21 days (for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine) or 28 days (for the Moderna version). To recap that answer: A second dose is better late than never, but it’s still best to be on time.

That discussion triggered a new question. One concerned reader was particularly interested in knowing whether it was OK to get a second dose of the Moderna vaccine on day 25 instead of on day 28.

To answer this, I returned to Dr. Diane Griffin, a virologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health who studies immune responses to viral infections and vaccines.

“Three days early for a four-week interval won’t matter much, but in general, the planned timing should be preserved,” she said. That’s because the body needs time to respond to the inoculation.

“Basically, what is happening during the interval is that the numbers of immune cells specific for the [coronavirus’ spike] protein are expanding in number and becoming ready to be stimulated to expand again with the second dose,” she explained.

An early second dose of the Moderna vaccine might make less of a difference than an early second dose of the Pfizer vaccine, because with only 21 days between doses there would be “fewer immune cells ready for restimulation,” she said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for what it’s worth, has recently updated its vaccination guidelines to say that second doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines that are “administered within a grace period of four days earlier than the recommended date for the second dose are still considered valid.” The agency also says that while the second dose should be given as close to the recommended interval as possible, if it can’t be done on time it can be scheduled up to 6 weeks after the first dose.

“I would go with CDC recommendations and personally would choose a few days late over early, but this is not based on data to say that one is better than another,” Griffin said. “Considering the difficulty some people are having with scheduling, I think that perfection is the enemy of the good.”

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask. Here’s how to do it right.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.