Coronavirus Today: The elusive antibody treatment

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Thursday, Jan. 21. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

You may have heard about monoclonal antibody therapy, the type of treatment touted by Donald Trump after he was hospitalized with COVID-19. The Food and Drug Administration authorized its emergency use to help keep high-risk coronavirus patients from becoming critically ill or even dying. But across the country, patients who are eligible for the treatment have not had it offered to them as an option — and many don’t even know that it exists.

Even for some of those who do know and seek it out, getting access to antibody treatments has been an uphill battle. Take Gary Herritz, a liver transplant recipient who tested positive for the virus and who knew that his compromised immune system made him vulnerable to a severe case of COVID-19. He asked his primary care doctor about monoclonal antibodies, but the doctor wasn’t sure Herritz qualified for the treatment. He called his transplant team to see if they could help but didn’t hear back. He spent two days punching in phone numbers for health officials in four states before he finally secured an appointment to receive the antibodies through an IV.

“I am not rich, I am not special, I am not a political figure,” Herritz, a 39-year-old former community service officer, wrote on Twitter. “I just called until someone would listen.”

The federal government has signed contracts to buy nearly 2.5 million doses of antibody treatments, with a price tag of more than $4.4 billion. More than 785,000 doses have been allocated, and more than 550,000 have been delivered to sites across the country. But so far, only about 30% of the doses delivered have been administered to COVID-19 patients, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

“The bottleneck here in the funnel is administration, not availability of the product,” said Dr. Janet Woodcock, a veteran FDA official in charge of therapeutics for Operation Warp Speed.

That’s a problem, because the therapy is most effective if given within 10 days of a positive coronavirus test. But patients are missing this crucial window because the patchwork nature of our healthcare system can delay testing and diagnosis.

Some health systems haven’t even offered the antibody therapies because doctors weren’t persuaded by the research results used to justify their emergency use authorization. “A lot of doctors, actually, they’re not impressed with the data,” Dr. Daniel Griffin, an infectious diseases expert at Columbia University, said on his podcast “This Week in Virology.” “There really is still that question of, ‘Does this stuff really work?’”

But as more patients are treated, there’s mounting evidence that the therapies can keep high-risk patients out of the hospital. That has two benefits: It eases patients’ recovery, and it reduces the burden on health systems that are struggling with overwhelming numbers of patients.

Dr. Raymund Razonable, an infectious diseases expert at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said he has treated more than 2,500 COVID-19 patients with monoclonal antibody therapies, and the results are looking good, with reductions in hospitalizations, intensive care admissions and mortality.

HHS officials have partnered with hospitals to set up infusion centers in California, Arizona and Nevada. One of them is at El Centro Regional Medical Center in Imperial County, a farming region east of San Diego with one of the state’s highest infection rates. The new walk-up infusion site has already put a dent in the influx of COVID-19 patients: More than 130 people have received the two-hour infusions and then been sent home to recuperate.

“If those folks would not have had the treatment, they would have come through the emergency department and we would have had to admit the lion’s share of them,” said Dr. Adolphe Edward, the medical center’s chief executive.

The key is to make sure people in high-risk groups know to seek out the therapy and get it early, Edward said. Greater awareness is also a goal of the larger federal effort, officials say. But patients like Herritz say that so far, awareness is looking like a distant goal.

“I think it’s horrible that if I didn’t have Twitter, I wouldn’t know anything about this,” he said. “I think about all the people who have died not knowing this was an option for high-risk individuals.”

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 6:33 p.m. PST Thursday:

Track the latest numbers and how they break down in California with our graphics.

Across California

Vaccine supply is becoming a critical problem in California as some counties say they’re quickly running out. Officials say they have large vaccine centers and the personnel to run them; all they’re missing are enough shots.

“Our ability to protect even more L.A. County residents in the coming weeks and months is entirely dependent and constrained by the amount of vaccine we receive each week, and often, we do not know from one week to the next how many doses will be allocated to L.A. County,” said L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer.

This has translated into confusion and frustration. Elizabeth Kostas, a Carmel Valley dental hygienist, said it took her 10 tries to schedule an appointment at a mass COVID-19 vaccination site. She raced to fill in her information each time she saw an open slot, only to be told there were no longer available spots, forcing her to start over.

“If I got ill and I hadn’t acquired that appointment, how am I going to feel? That’s a horrible feeling,” said Kostas, who added that she had the same issue when trying to schedule an appointment through her healthcare provider. “I don’t mean to sound alarmist or emotional, but it’s a matter of life and death.”

Under pressure because of the slow vaccine rollout, Gov. Gavin Newsom set an ambitious target in early January of vaccinating an additional 1 million people over a 10-day period. He even urged Californians to “hold me accountable” to that goal. But nearly two weeks later, due to a series of data collection problems, state officials can’t seem to offer clear evidence on whether the effort succeeded or failed.

It’s likely that Newsom hit the 1 million mark over 12 days rather than the promised 10, a California Department of Public Health spokesperson said, adding that coding errors and data lags have hindered the state’s efforts to accurately count and publicly report the daily count.

Speaking of vaccines, yesterday’s newsletter reported that Orange County residents who got a dose of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine were being asked to check their vaccination cards to see if their shots were from lot number 021L20A. I got that wrong; the lot number to look out for is actually 041L20A. (Sorry!)

In L.A. County, the chance that a person hospitalized for COVID-19 will end up dying has doubled in recent months, according to an analysis by the county’s Department of Health Services. The report finds that the chances of death while hospitalized rose from about 1 in 8 in September and October to roughly 1 in 4 since early November. Since hospitalized COVID-19 patients are now more uniformly severely ill, a larger percentage of them are more likely to die, said Dr. Roger Lewis, the director of COVID-19 hospital demand modeling for the agency.

These higher odds have emerged during a devastating spike in the county’s death toll, my colleagues Rong-Gong Lin II and Luke Money write: In early November, when the current surge began, there were fewer than 20 deaths per day, on average. But over the weeklong period ending Wednesday, there were roughly 206 deaths reported each day, data compiled by The Times show.

To give you a sense of how quickly things deteriorated, consider this: More than 14,000 people have died in L.A. County over the course of the pandemic, but more than 4,000 of those people have died just since New Year’s Day. Keep in mind that the county accounts for roughly a quarter of the state’s population, but about 41% of its 35,000 COVID-19 deaths.

At the twin ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, nearly 700 dockworkers have been infected with the coronavirus and hundreds more are taking virus-related leaves, triggering fears of a serious slowdown in the region’s multibillion-dollar logistics economy, my colleague Margot Roosevelt writes. The rising infection rate among longshore workers is worsening a massive snarl at the ports due to a pandemic-induced surge in imports. That’s a large part of why port executives, union leaders and elected officials are calling for authorities to start vaccinating dockworkers if they want to avoid a critical labor shortage.

“Without immediate action, terminals at the largest port complex in America may face the very real danger of terminal shutdowns,” Rep. Nanette Diaz Barragan (D-San Pedro) and Rep. Alan Lowenthal (D-Long Beach) wrote to state and county health officials on Jan. 15. “This would be disastrous not only for the communities of the South Bay, but also the entire nation which relies upon the vital flow of goods through these ports.”

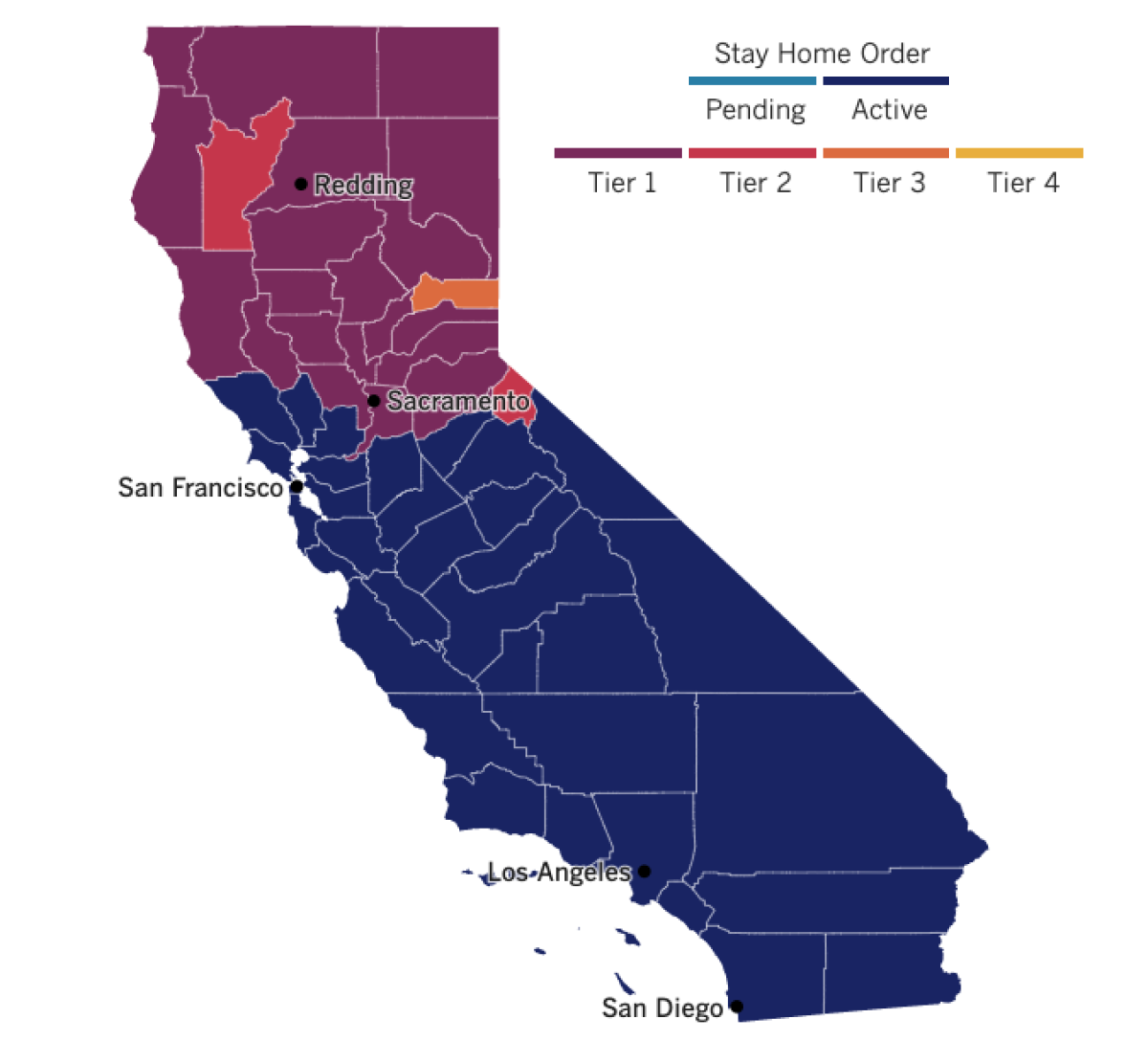

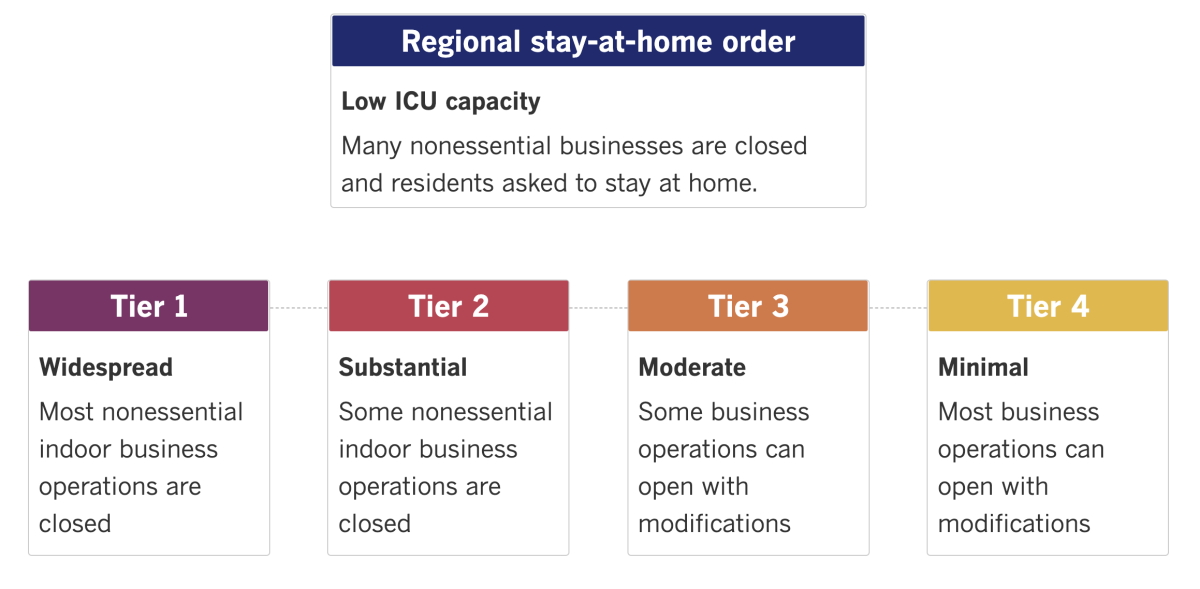

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

President Biden kicked off his first full day in office with a burst of 10 executive orders aimed at jump-starting his national COVID-19 strategy. The executive orders are intended to ramp up vaccinations and testing, lay the groundwork for reopening schools and businesses and boost the use of masks, especially on many planes, trains, buses and other forms of public transportation.

“We didn’t get into this mess overnight, and it’s going to take months for us to turn things around,” Biden said. Then he offered this reassurance: “To a nation waiting for action, let me be the clearest on this point: Help is on the way.”

The moves signaled the new administration’s far more aggressive approach to containing the virus, starting with strict adherence to public health guidance. But with the virus actively spreading in most states and the vaccine rollout still bumpy, Biden faces major hurdles. There’s also uncertainty over whether Republicans in Congress will support the new president’s $1.9-trillion economic relief and COVID-19 response package.

Amazon is offering its operations network and advanced technologies to assist Biden in his promise to get 100 million vaccinations to Americans in his first 100 days in office. The company said it had already arranged for a healthcare provider to administer vaccines to its employees when the doses become available, and that its workers — most of whom cannot work from home — should be inoculated as early as possible.

California, meanwhile, has been trying to determine whether Amazon is doing enough to protect its workers from the virus. Last month, the state sued the online retail giant in an effort to force it to comply with its investigation, and in October, Cal/OSHA levied fines for safety violations at two Southern California warehouses. Labor advocates said the $1,870 fines were too small to motivate the company to do better.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, Biden’s top pandemic advisor, said the U.S. will resume funding for the World Health Organization and join its consortium aimed at sharing coronavirus vaccines fairly around the world. The move marks a dramatic and overt shift toward a multilateral approach to fighting the pandemic after the Trump administration had pulled away from the global health agency.

Fauci said the Biden administration “will cease the drawdown of U.S. staff seconded to the WHO” and resume “regular engagement” with the agency. “The United States also intends to fulfill its financial obligations to the organization,” he added.

The U.S. had long been the WHO’s biggest donor — until Trump’s go-it-alone stance deprived the agency of needed funding during a deadly worldwide health crisis. “This is a good day for WHO and a good day for global health,” said Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in response to the U.S. announcements. “The role of the United States, its role, global role is very, very crucial.”

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: When will all the folks who aren’t healthcare workers, nursing home residents or at least 65 years old be eligible to get a vaccine?

It’s a pressing issue on the minds of many Californians after the priority vaccine line, which until recently was limited to healthcare workers and residents of long-term care facilities, was expanded to include the state’s senior population.

I don’t have great news on this front, but here goes: Vaccinating Californians ages 65 and up could take until June to complete, according to state epidemiologist Dr. Erica Pan. This would push back vaccine access for people not currently on the priority list for at least four months, based on Pan’s estimate.

Right now, the federal government is shipping vaccines at the rate of 300,000 to 500,000 doses per week — though if the new presidential administration speeds up shipments, the pace of vaccinations could rise.

L.A. County, for instance, has a robust network of more than 200 hospitals, pharmacies and other healthcare providers ready to vaccinate the public, Ferrer said. “We have a lot of potential in the system to really be able to push out lots of vaccines, but we don’t have lots of vaccines to push out,” Ferrer said.

After healthcare workers, nursing home residents and Californians ages 65 and up get their shots, the state has outlined a schedule of who gets the vaccine next. Take a look and see where you are in the line. Just know that for now, the timing of when we’ll move down this list remains unclear.

Phase 1B

- People at risk of exposure while at work in these sectors: education, child care, emergency services, food and agriculture.

- Those at risk of exposure while at work in these sectors: transportation and logistics; industrial, commercial, residential and sheltering facilities and services; critical manufacturing.

- People who live in congregate settings with outbreak risks, such as those who are incarcerated or homeless.

Phase 1C

- People ages 50 to 64.

- People ages 16 to 49 who have an underlying health condition or disability that increases their risk of severe COVID-19.

- Those at risk of exposure at while at work in these sectors: water and wastewater; defense; energy; chemical and hazardous materials; communications and IT; financial services; government operations; and community-based essential functions.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask. Here’s how to do it right.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.