Coronavirus Today: The big school reopening debate

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Thursday, Jan. 7. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Folks, it’s been a hard couple of days, with a lot to process. Yesterday might have been one of the few times in recent months when the pandemic wasn’t necessarily top of mind. But the virus continues to spread without respect for other crises — so join me in taking a break from our national troubles to consider the dilemma schools face across California.

Last week, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a $2-billion incentive package to encourage the reopening of in-person classes for elementary school students as early as mid-February. The plan is sparse in important details — but in the best-case scenario, large numbers of elementary schools across California would open as early as mid-February for kids in kindergarten through second grade, and all other elementary students would come back as soon as March. Newsom did not give a time frame for older students.

It’s an ambitious proposal — and it’s facing stiff resistance from seven of the state’s largest school districts. It’s also running into the hard fact that, in Los Angeles County at least, transmission rates are simply too high to consider bringing students back to campuses anytime soon.

In some of L.A.’s lower-income communities, nearly one in three asymptomatic students who are opting to get tested are turning out to be infected. The student positivity rate was 32% in the Maywood, Bell and Cudahy communities and 25% in Mid-City, according to data from L.A. Unified. Even in higher-income neighborhoods where the student positivity rate is in the single digits, it has still shot up, a reflection of the surge affecting California at large.

Under conditions like these, practically any school would run the risk of frequent disruptions, experts say. A campus may have to shut down if it records three infections over a 14-day period, a situation that isn’t hard to imagine.

Many school districts have already decided against reopening their doors for the time being. Pasadena Unified, Alhambra Unified and the ABC Unified School District in the Cerritos area had planned to reopen campuses to some extent this month, but all have put those plans on hold.

And more may soon join them. On Thursday, L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer urged all K-12 schools to shut down until the end of January, though she stopped short of ordering them to do so. The high prevalence of the coronavirus in the community means the danger is simply too great to continue to provide in-person services and instruction except in rare cases where it is absolutely necessary, Ferrer said. She also called for a pause in athletic conditioning.

“I’m strongly recommending that schools not reopen for in-person instruction,” Ferrer said on a call with school leaders. “I’m recommending this for three weeks until the end of January.”

In his announcement last week, Newsom cited the harms of learning loss and social isolation due to the pandemic-caused school closures, particularly for Black and Latino students from financially strapped families.

But in a letter sent to Newsom on Wednesday, superintendents from seven of the state’s largest school districts found a possible weakness in the governor’s plan: Because coronavirus transmission rates in Los Angeles and other cities that serve some of the state’s neediest families aren’t likely to meet the governor’s threshold of no more than 28 confirmed cases per 100,000 people, it could mean that funds that would normally be spent on schools serving lower-income students would instead be spent in more affluent communities.

That would reverse “a decade-long commitment to equity-based funding” of schools, the superintendents wrote.

They also called on Newsom to set a clear and mandatory state standard for reopening campuses.

“Our schools stand ready to resume in-person instruction as soon as health conditions are safe and appropriate. But we cannot do it alone,” the superintendents from Los Angeles, Long Beach, San Diego, San Francisco, Oakland, Fresno and Sacramento wrote in the letter. “Despite heroic efforts by students, teachers and families, it will take a coordinated effort by all in state and local government to reopen classrooms.”

By the numbers

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 6:49 p.m. PST Thursday:

Track the latest numbers and how they break down in California with our graphics.

Across California

Around Nov. 1, when the current wave of the pandemic began washing over Los Angeles County, only about one in every 25 coronavirus tests were coming back positive. Now that rate is five times as high, with close to 1 in 5 tests confirming infection. It’s a simple yet devastating illustration of how far and wide the virus has spread.

This means it’s easier than ever to be infected with the coronavirus. Even activities that might have been performed safely a few months ago now carry far higher risk. “When so many people are positive, the need for precautions significantly increases,” Ferrer said.

And the more people who are infected, the more who are likely to become seriously ill with COVID-19 and require hospital care in a system already stretched to the breaking point. Ultimately, more people will die.

“People who were otherwise leading healthy, productive lives are now passing away because of a chance encounter with the COVID-19 virus,” Ferrer said. “This only ends when we each make the right decisions to protect each other.”

The rising death toll is overwhelming funeral homes and causing officials to send refrigerated trucks across the state to hold corpses. The National Guard has been called to L.A. County to help with the temporary storage of bodies at the county medical examiner-coroner’s office, relieving pressure on hospital morgues and private mortuaries that have simply run out of space.

L.A. County Supervisor Janice Hahn had requested that the Navy hospital ship Mercy return to help with the surge in Southern California. But the state said this week that the Mercy “is now under mandatory maintenance, in dry dock, and not available for deployment.” Instead, California is asking for an additional 500 federal medical personnel, officials said Wednesday.

County health leaders are worried that the region is losing too much ground in its battle with COVID-19. Only immediate and decisive changes in Southern Californians’ behavior can stem a steep rise in deaths. “This is a health crisis of epic proportions, and we need everyone — I mean everyone — to use the tools right in front of them to help us drive down transmission of this deadly virus,” Ferrer said.

California logged nearly 38,000 new coronavirus cases on Wednesday. The statewide daily total has flattened to about 39,000 over the last week, modestly lower than the peak of 45,000 new cases per day in mid-December. But experts worry that the counts will start climbing again by week’s end as people exposed to the virus over Christmas and New Year’s begin to experience symptoms and get tested.

Meanwhile, the state unemployment agency has suspended payments on 1.4 million benefit claims as it tries to get a handle on rampant fraud. It’s the latest controversy for an agency whose jammed phone lines, computer glitches and operational problems have left hundreds of thousands of jobless Californians without financial help, sometimes for months.

The Employment Development Department has processed an unparalleled 18.5 million claims and paid out $110 billion in benefits since the pandemic began closing businesses and putting people out of work. At the same time, authorities are investigating whether the agency has paid out more than $4 billion in fraudulent claims — including what one analysis finds were more than $42 million worth sent to out-of-state prison and jail inmates.

State Sen. Mike McGuire (D-Healdsburg) acknowledged the risk of fraud but said the EDD “over-corrected” in suspending payments, causing his office to be inundated with calls from panicked constituents trying to understand why their benefits were cut off. “Casting this wide net and suspending payments to law-abiding Californians is impacting the lives of tens of thousands of innocent residents struggling to pay their rent and put food on the table,” McGuire said Thursday.

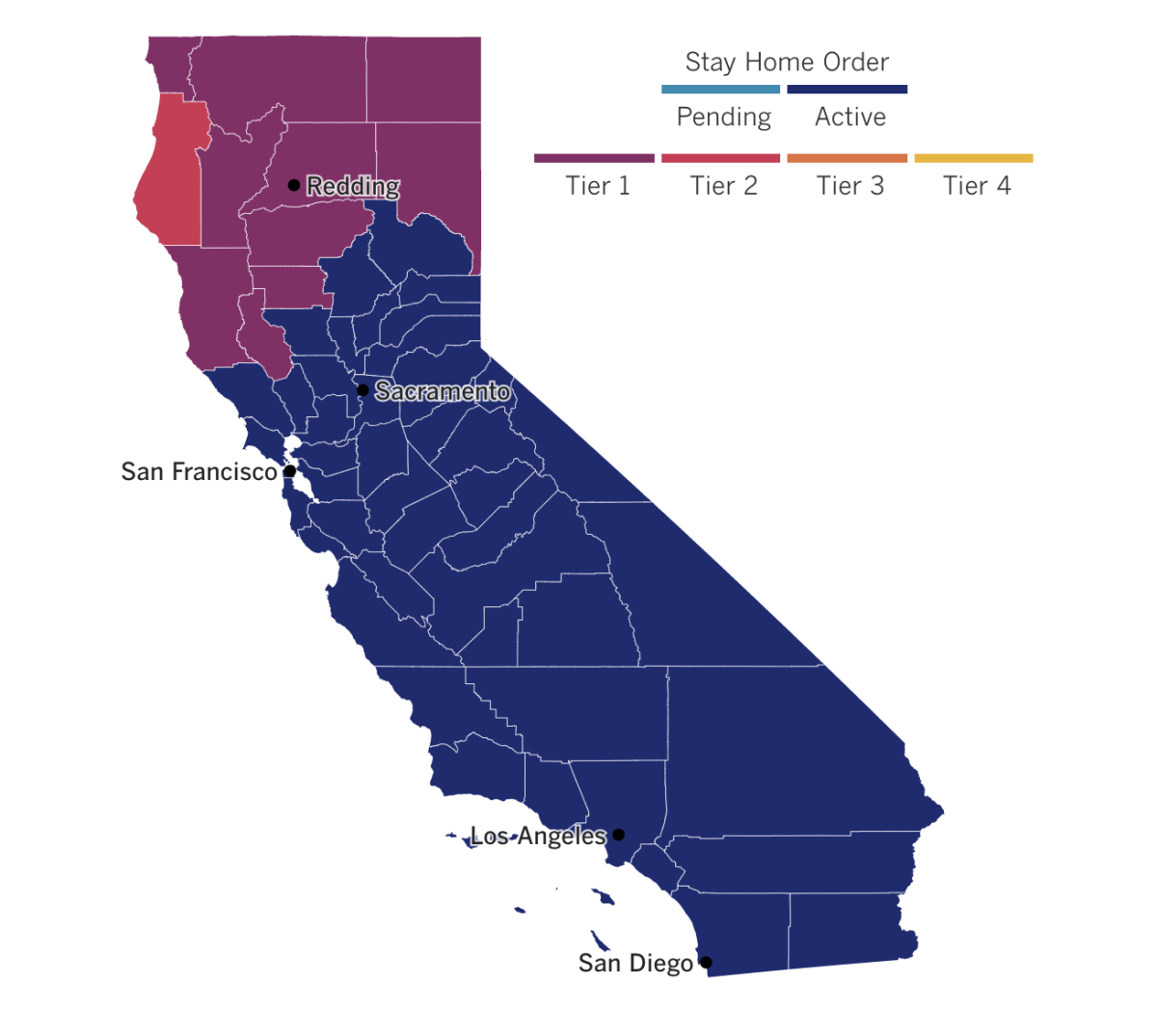

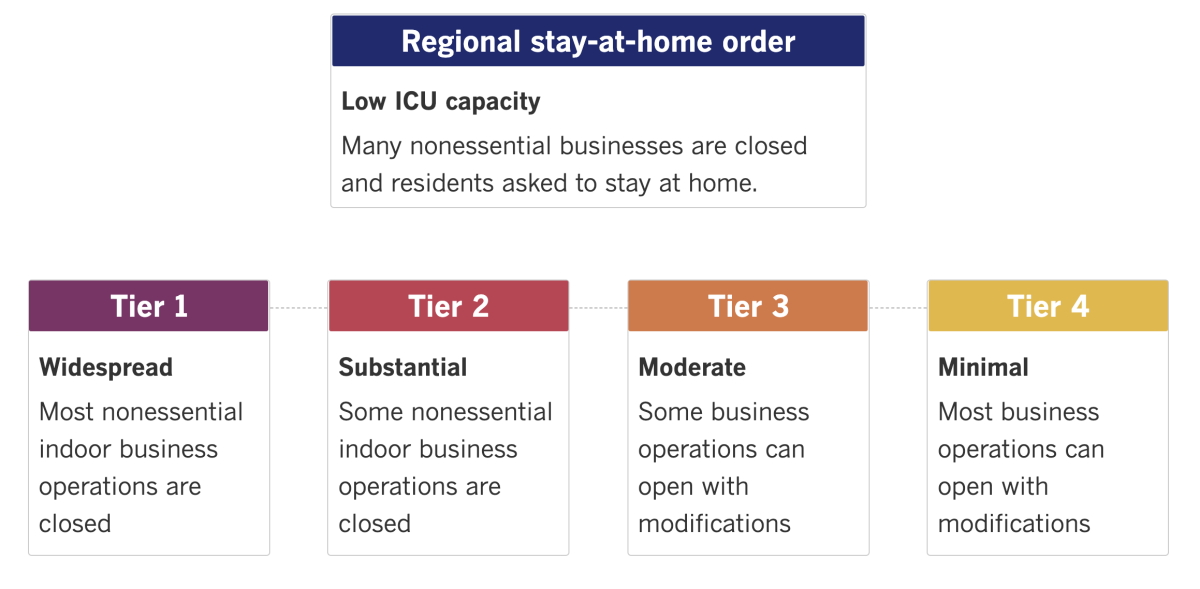

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

Israel is vaccinating its population against COVID-19 far faster than other countries, which could push it to herd immunity in record time. But it’s also facing criticism for leaving behind the nearly 5 million Palestinians under its control in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, who are expected to wait considerably longer for mass inoculation, special correspondent Noga Tarnopolsky writes.

In less than three weeks, Israel has vaccinated almost 15% of its 9.3 million people with the first of two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. (By comparison, the U.S. rate hovers around 1.5%.) The rollout may allow Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu — now up for reelection while facing trial for bribery, fraud and breach of trust — to improve his lackluster poll numbers and inoculate himself against harsh criticism of his overall management of the pandemic response.

A consortium of 15 Israeli and Palestinian human rights organizations has called on Israel to ensure that high-quality vaccines be delivered to Palestinian lands as soon as possible. Israeli officials have said that some leftover doses may be donated, but no formal plans are in place — and that Israel’s first responsibility is to its own citizens. Others have argued that the country bears additional moral, and perhaps legal, responsibilities.

“I am so proud of how well our HMOs have provided vaccinations to Israelis, including the Palestinian citizens of Israel and residents of occupied East Jerusalem,” Israeli lawyer and activist Daniel Seidemann said in an online posting. At the same time, he said, “I am so ashamed of how we’ve failed to provide vaccinations to the Palestinians we occupy in the West Bank and Gaza.”

In Mexico City, people stood in line with empty oxygen tanks to take advantage of the city‘s offer of free oxygen refills for COVID-19 patients. As the virus spreads, the demand for oxygen has driven up prices and made lines long.

The capital city has seen a surge in coronavirus infections that is straining oxygen supplies. In a city where people are afraid to go to hospitals, getting oxygen refills has become a matter of life and death.

Iván, an employee of one oxygen refill store, said there wasn’t always enough to go around. “There are times when we don’t have enough oxygen to fill everybody’s tanks completely,” he said. “There are times when we have to reduce the refill, so that everybody who is in line can at least bring some oxygen home to their relatives.”

If you’re considering getting on a plane anytime soon, this might make you think twice: Visibly ill people are still being allowed to board, my colleague Hugo Martín reports.

U.S. airlines say they have layers of protocols intended to protect passengers, including cleaning plane cabins, requiring face coverings except when eating or drinking, and requiring passengers to fill out health declarations. Nearly all of them also require passengers to fill out a health declaration before boarding. But the only repercussion for lying on the form or refusing to wear a mask is getting banned from the airline if caught.

Take the tragic case of Isaias Hernandez, who boarded a United Airlines flight from Orlando, Fla., to Los Angeles after the airline says he stated on a checklist that he had not been diagnosed with COVID-19 and didn’t have any symptoms. He collapsed once the flight was in the air. Three passengers gave him CPR for nearly an hour, and the flight was diverted to Louisiana, where Hernandez was pronounced dead. The coroner’s report listed the cause as “acute respiratory failure, COVID-19.”

How often do people with COVID-19 board planes? It’s impossible to know. Read the full story here.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: How will I know when to get my second dose of COVID-19 vaccine?

As the vaccine rollout continues its somewhat slow and bumpy start, many folks are wondering who’s keeping track to make sure people get the correct second dose, and that they get it on time. To answer some of those questions, we’ve published a look at how the vaccinations are being tracked and who has access for this information. A few main points to keep in mind:

What to expect for your first shot: Once vaccines become widely available, the doctor’s office, clinic or pharmacy you go to will ask for basic info, such as your name, birth date and gender. You also might be asked about other things, such as your race and any underlying health conditions that could put you at risk of severe COVID-19. The shots are free, but you’ll probably be asked for your insurance information if you have it.

A second-shot reminder: You will get a vaccination record card saying when and where you got your first shot, as well as what kind it was. Doctor’s offices, clinic and pharmacies may also send reminders via text, email or phone. Doses made by Pfizer and BioNTech are supposed to be given three weeks apart, while doses made by Moderna should be four weeks apart. The timing does not have to be exact: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say that doses given within four days of those targets are fine.

A record of your vaccination: Providers should have your record in their system. They’ll also enter the information in state or local immunization registries that are used to log childhood and other vaccinations. That way, if you go to another location for your second shot, workers should be able to look up information about your first dose.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them.

Resources

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask. Here’s how to do it right.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.