Coronavirus Today: Why L.A. is uniquely vulnerable

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Monday, Dec. 28. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

By Thanksgiving week in Los Angeles County, 4,000 people were testing positive for the coronavirus each day — a record at the time. Now, after people traveled and gathered for that holiday in spite of health officials’ pleas, the county averages 14,000 cases per day.

The exploding number of COVID-19 patients is making intensive care unit beds vanishingly scarce and causing apocalyptic scenes to play out in hospitals large and small. “Ambulances are circling hospitals for hours trying to find one that has a bed open so they can bring in their critically ill COVID patient gasping for air,” a doctor at one of the county’s public hospitals said. “We’re literally hanging on by a thread.”

It’s no secret that the surge-upon-a-surge has been particularly devastating in Los Angeles, which was hit by the same trifecta of pandemic fatigue, winter weather and holiday travel that has plagued the nation at large. But L.A. seems to have suffered a disproportionate toll.

Now, after speaking with a phalanx of experts and officials, my colleagues Soumya Karlamangla and Rong-Gong Lin II lay out in detail the reasons why L.A. was uniquely vulnerable to a COVID-19 catastrophe. Here are a few big ones:

A high “social vulnerability” score: This metric was developed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to measure how severely a region may be affected by a natural disaster or disease outbreak, based on factors like average income, education and housing status. L.A. County’s score is worse than anywhere in the Bay Area or in nearby Orange and Ventura Counties — a sign that L.A. was bound to have a harder time facing a COVID-19 surge without experiencing deadly consequences.

“That’s what’s come home to roost: that Los Angeles has the combination of poverty and density that leads to a virus like this being able to spread much more quickly and be more devastating,” said Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti.

An expensive housing market: Crowding, a measure of how many people live in a home, plays a big role in aiding the virus’ spread in L.A. (This is distinct from population density, a measure of how many people live in a geographical area.) Thanks to sky-high housing costs, it’s common for a working-class family of four, five or more to share a one-bedroom apartment. In fact, L.A. has the highest percentage of overcrowded homes out of the 25 biggest metropolitan areas in America — its 11% is nearly double New York’s 6%.

An analysis in a medical journal found that the odds of becoming ill with COVID-19 rose as overcrowding worsened. That makes sense, since a cramped home offers little private space for an infected person to isolate and prevent others from getting sick. (Those odds, if you’re curious, were not significantly affected by a neighborhood’s density or poverty rate.)

“The more people you have infected, and the more densely people are housed, the more links there are going to be,” said UC San Francisco epidemiologist Dr. George Rutherford.

Tuning out of public health messaging: Some people appear to be fed up with the county’s health directives, such as the ban on outdoor restaurant dining. And some experts say that overly strict rules, such as a now-reversed closure of playgrounds and ban on small outdoor gatherings, have sown distrust and criticism in the once-compliant public and allowed for misinformation to spread.

Dissenting views from elected public officials have probably eroded adherence even further. “That’s a disaster for us,” said Barbara Ferrer, L.A. County’s public health director.

Ferrer said the evidence is on the streets. In the spring, “I would drive to work each day, and there would be, like, two cars on the road — nobody was out. And we definitely don’t have that this time around,” she said. “I don’t think people are listening as much.”

By the numbers

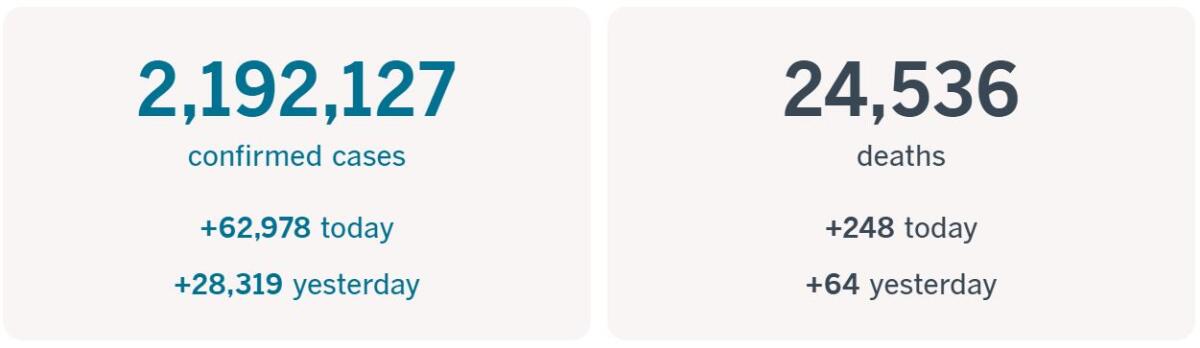

California cases and deaths as of 5:45 p.m. PST Monday:

Track the latest numbers and how they break down in California with our graphics.

Across California

December has clearly been the worst month of the COVID-19 pandemic in California, and officials also expect January to be very, very bad. While they’re not sure exactly how much sickness and death they’ll face, it’s clear the holidays are creating “viral wildfire,” said Dr. Robert Kim-Farley, an infectious disease expert at UCLA. That’s fueled in part by a high infection rate — about 1 in 95 Los Angeles County residents are contagious with the virus, officials’ estimates show.

Doctors, nurses and hospital systems are bracing for the surge in hospitalizations that will propbably come in the weeks after Christmas and New Year’s celebrations. Some L.A.-area hospitals are already running low on their supplies of oxygen, which is critical for treating severely ill COVID-19 patients. They’re also running short on other necessities, such as the special plastic tubes used to bring oxygen into the lungs.

Kaiser is postponing non-urgent and elective surgeries and procedures throughout California as it struggles with a deluge of critically ill COVID-19 patients. The pause will remain in effect through Jan. 10 in Kaiser’s Southern California region and through Jan. 4 in Northern California, officials said.

“It’s getting worse, and we haven’t even hit the Christmas or New Year’s surge yet, so I feel like the number of people that are going to die because the hospital system is beyond overwhelmed will shoot up,” one doctor at an L.A. County hospital said.

Of great concern are New Year’s gatherings, which could spread the virus even further. Officials are also keeping an eye on crowded shopping malls, Ferrer said: The state’s regional stay-at-home order requires shopping malls to cap capacity at 20%, but those limits clearly aren’t being followed.

Adding to the anxiety are worries that a new and potentially more contagious strain circulating in Britain may have arrived in the Southland. L.A. County scientists have begun testing viral samples from local patients to see if the variant is here. Ferrer said a public health lab has begun the process. If the new strain does make its way into the Golden State, it’s unclear how it will affect efforts to contain the outbreak.

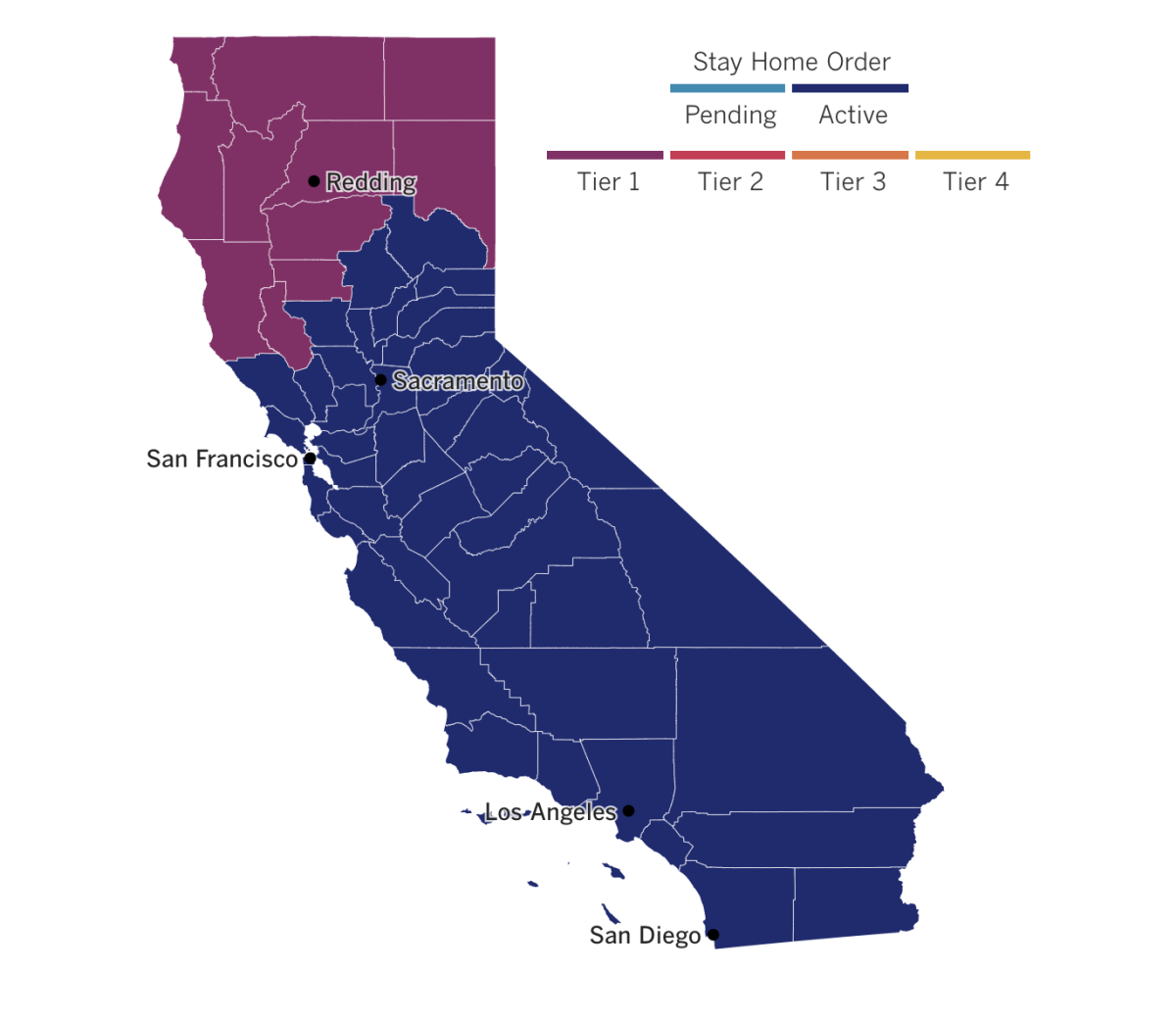

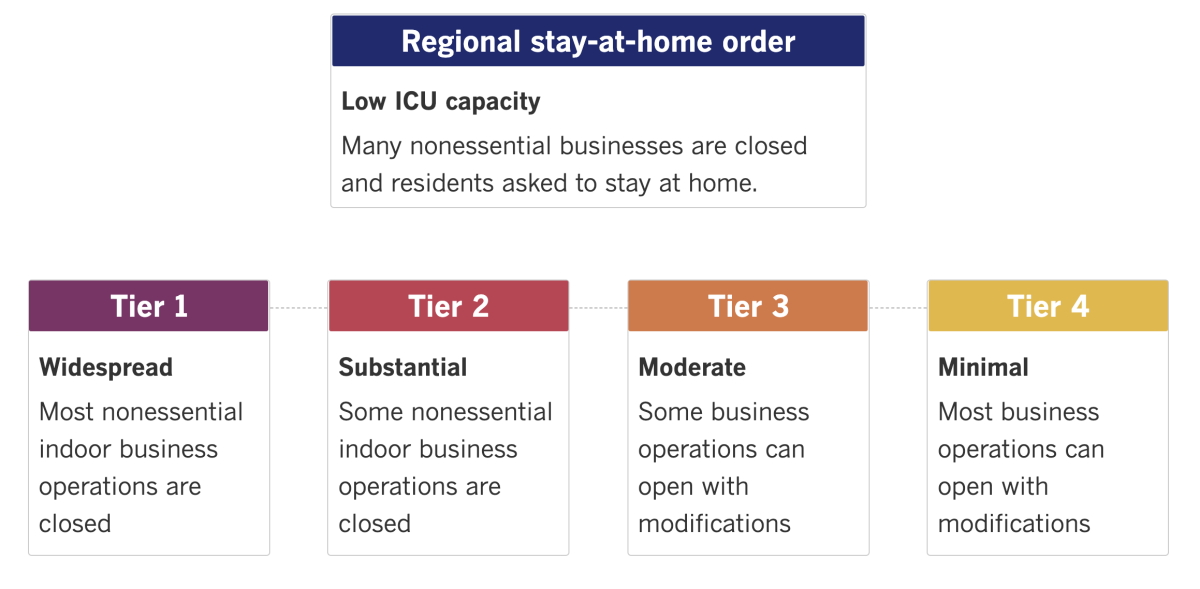

With the surge continuing and ICU bed capacity near zero in many parts of the state, California is poised to renew the regional stay-at-home orders that were set to last through today in Southern California. Gov. Gavin Newsom said Ghaly is likely to extend the orders for another three weeks when he discusses ICU projections on Tuesday. If you’re wondering what restrictions are currently in place in the Southland, here’s a helpful breakdown.

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

Kids are infected with the virus more often at gatherings than at school or daycare, according to a new study of nearly 400 children in Mississippi. Compared with children who tested negative, those who tested positive for the virus were more likely to have attended gatherings and have had visitors at home.

What’s more, parents or guardians of infected children were less likely to report wearing masks at those gatherings. The “lack of consistent mask use” in schools was also a factor in the virus’s spread, according to the study, which was conducted in partnership with the CDC and published in the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Protecting children from infection is crucial for keeping the state’s schools and day cares open, said Dr. Charlotte Hobbs, a professor of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and the study’s lead author. “We all know the vital nature of school for our children developmentally, academically and socially,” she said.

Across the Atlantic, European Union nations began vaccinating some of their most vulnerable citizens with the Pfizer-BioNTech shot over the weekend. For healthcare workers exposed to the coronavirus on a daily basis, the first injections offered emotional relief and a chance to urge the EU’s 450 million people to protect themselves and those around them.

“Today I’m here as a citizen, but most of all as a nurse, to represent my category and all the health workers who choose to believe in science,” said Claudia Alivernini, a 29-year-old nurse who was the first of five doctors and nurses to receive the vaccine at the Spallanzani infectious disease hospital in Rome. Italy was hit particularly hard in the early months of the pandemic, and it still has the continent’s worst confirmed death toll, with nearly 72,000 dead.

In Spain, a 96-year-old nursing home resident and a caregiver in Guadalajara were the first Spaniards to be vaccinated. “Let’s see if we can all behave and make this virus go away,” Araceli Hidalgo, the resident, said after receiving her injection.

On Christmas Eve, intensive care nurse Maria Irene Ramírez in Mexico City became the first person in Latin America to get an approved COVID-19 vaccine. “This is the best present I could have received in 2020,” she said. ”The truth is we are afraid, but we have to keep going because someone has to be in the front line of this battle.”

Chile also began its vaccination program on Thursday. Officials said the country has received 10,000 doses of the Pfizer vaccine and has a deal for a total of 10 million. Argentina has run into problems obtaining the Pfizer vaccine, and instead received 300,000 doses of the Russian Sputnik V vaccine. It plans to be the first country in Latin America to administer the Russian offering next week.

In Shanghai, a Chinese court sentenced a former lawyer who reported on the coronavirus outbreak in its early stages to four years in prison on charges of “picking fights and provoking trouble,” according to one of her attorneys. The Pudong New Area People’s Court sentenced Zhang Zhan following allegations that she spread false information, gave interviews to foreign media, disrupted public order and “maliciously manipulated” the outbreak.

In February, Zhang traveled to Wuhan, where the outbreak is believed to have emerged, and posted about it on social media platforms. She was arrested in May amid tough nationwide measures meant to curb the outbreak, along with heavy censorship to deflect criticism of the government’s initial response. Zhang reportedly went on a prolonged hunger strike while in detention, and authorities force-fed her. She is said to be in poor health.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Why isn’t more COVID-19 vaccine available?

I hear you. Many of us are itching to get our shots so that we can start moving through the world with some assurance of protection. And right now, it feels like those doses aren’t coming fast enough.

To truly control the pandemic, my colleague Samantha Masunaga points out, billions of people around the world need to be vaccinated. But by the end of this year, only about 70 million doses of vaccines — some made by Pfizer and BioNTech, some developed by Moderna and the National Institutes of Health — are expected to be shipped worldwide.

Ultimately, experts say that designing, producing and distributing COVID-19 vaccine is a major challenge — and all things considered, it’s happening pretty fast.

“I don’t think we’ve seen anything quite on this scale,” said Eugene Schneller, a professor of supply-chain management at Arizona State University. “Although you’d like to have more ... I think we’ve done and are doing pretty well.”

To make more vaccine in very short order, production needs to be expanded to more factories, which need to be outfitted with special equipment. Workers need to be trained too. Instead of spending time and money to build new factories, pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer and Moderna are largely turning to contractors that specialize in vaccine manufacturing.

Even if production and shipping could be immediately ramped up, there would still be a bottleneck: finding enough places to store of all those doses in a deep freeze until they’re ready to be used. Both Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines — the only ones currently authorized for emergency use in the U.S. — must be kept at extremely low temperatures, so they can’t be stowed just anywhere. To that end, L.A. County has acquired more than a dozen ultra-cold storage freezers to store the vaccine before it’s distributed.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them.

Resources

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask. Here’s how to do it right.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.