Coronavirus Today: The rich want to jump the line

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Friday, Dec. 18. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus, plus ways to spend your weekend and a look at some of the week’s best stories.

A COVID-19 vaccine has been out for less than a week, and the rich people who want it first are already looking for ways to jump to the front of the line. They’re offering tens of thousands of dollars in cash, making their personal assistants pester doctors daily, and asking whether five-figure donations to a hospital would, in every sense of the phrase, give them a shot, my colleagues Laura J. Nelson and Maya Lau write.

“We get hundreds of calls every single day,” said Dr. Ehsan Ali, who runs Beverly Hills Concierge Doctor. His clients, who include Ariana Grande and Justin Bieber, pay between $2,000 and $10,000 a year for personalized care. “This is the first time where I have not been able to get something for my patients.”

The Food and Drug Administration granted emergency use authorization to a second COVID-19 vaccine late Friday, allowing the shot developed by Moderna and the National Institutes of Health to be used in adults 18 and older. A very similar vaccine from Pfizer and BioNTech got the same OK last Friday.

Even though the number of authorized vaccines has doubled, the first doses are in short supply, which is why California has laid out a strict order for vaccinations based on need and risk. Healthcare workers and nursing home residents get top priority, followed by essential workers and those with chronic health conditions. Finally, vaccinations will be made available to the wider public. Yet that hasn’t stopped those with money, power and influence from trying to cut in front of teachers, farmworkers and firefighters.

Meanwhile, the most vulnerable Californians are even more exposed than before. About 1 in 80 people in L.A. County are now contagious with the virus, more than 10 times the rate in late September, when scientists calculated that 1 in 880 county residents were infectious. The elderly and people of color are being hit disproportionately hard in this latest surge, the worst since the pandemic began.

For some perspective: The death rate among L.A. County’s white residents has remained stable, at about one to two per day per 100,000 white residents. In contrast, death rates for Latino, Black and Asian residents are shooting up. Among Latino residents over the last four weeks, the death rate has jumped from 1.4 to 4.5 daily deaths per 100,000 Latino residents.

Many Latinos are vulnerable in part because they’re essential workers who must go to retail stores, manufacturing plants and other sites. They don’t have the option to work from home, which means they’re at higher risk of coming into contact with an infected person. Some Latino neighborhoods are more densely populated, making it easier for the virus to spread.

Death rates for Black residents have jumped from less than 1 death per 100,000 to more than three deaths per 100,000. Likewise, Asian residents have seen their death rate rise from 0.5 per 100,000 to three deaths per 100,000.

“The widening gaps are stark reminder that many of our essential workers are Black and brown, and many are not able to telework or stay home,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said. “Many work at jobs with low wages, and many live in underresourced neighborhoods.”

And if there are more super-spreader events come Christmas and New Year’s, the effects will continue to be felt unevenly across the region. That’s because people living in the most impoverished parts of the county are also more likely to die of COVID-19.

“The death rate among people living in the lowest-resource areas is now four times that of people living in areas with the most resources,” Ferrer said. “And unfortunately, this gap, too, looks to be growing.”

These two stories provide yet another startling reminder of the very different realities faced by the rich and privileged on one hand and the poor and vulnerable on the other.

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 5:31 p.m. PST:

Track the latest numbers and how they break down in California with our graphics.

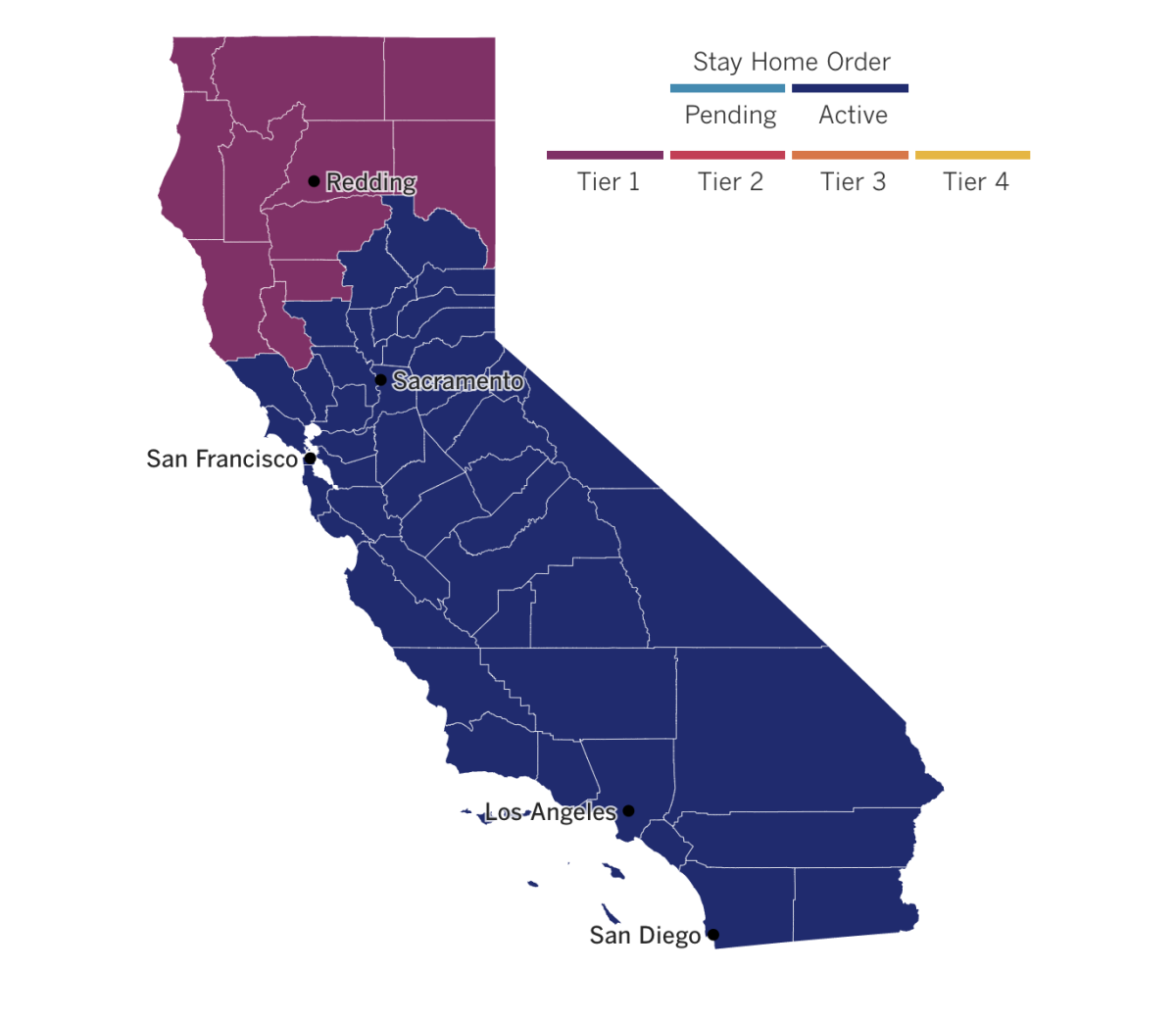

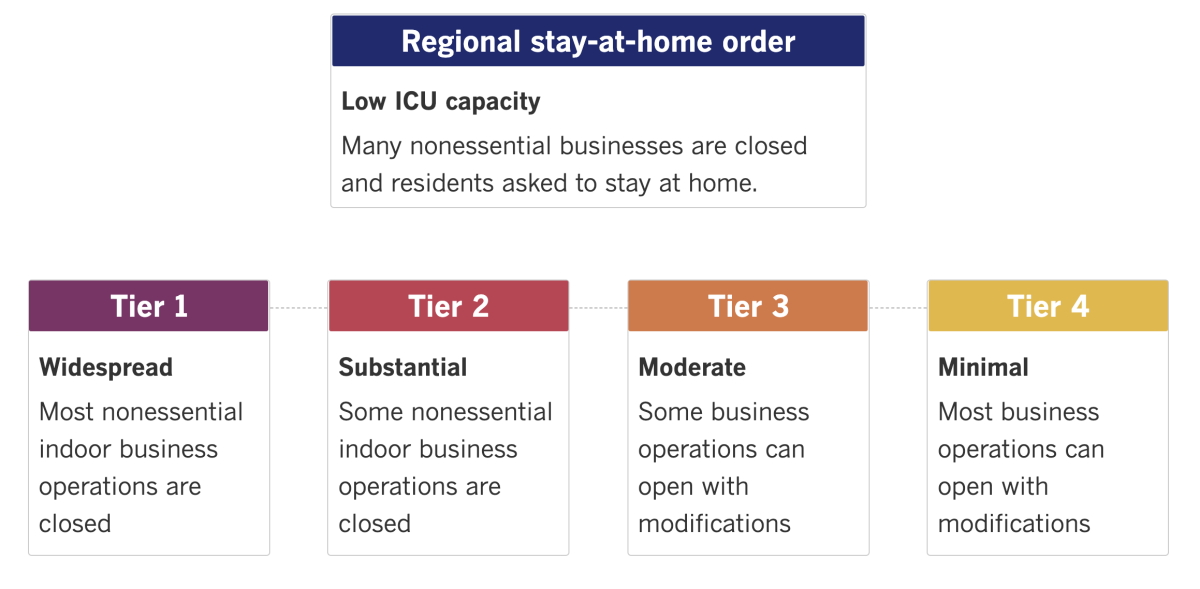

See the current status of California’s reopening, county by county, with our tracker.

What to read this weekend

“Tell it to the people that are losing their f— homes”

By now you’ve surely heard about Tom Cruise’s expletive-filled corona-rager aimed at two crew members who were seen violating social distancing protocols on the set of “Mission: Impossible 7.” All culture columnist Mary McNamara wants to know is: Can we put it on some sort of national emergency broadcast loop?

“I don’t ever want to see it again — ever!” Cruise shouts in an audio recording of the tirade. “If I see you do it again, you’re f— gone. … That’s it! No apologies. You can tell it to the people that are losing their f— homes because our industry is shut down.”

The 3½-minute diatribe is definitely “a lot,” McNamara acknowledges. And it must be deeply upsetting for those on the receiving end (particularly since, I suspect, Cruise is in a position of power over them). But as infections and deaths continue to skyrocket, there’s no denying that the more reasonable entreaties by public health officials are not working.

Perhaps Tom Cruise screaming profanities “may be exactly what we need,” McNamara suggests.

Death in Room 311

Chouphaphone “Judy” Bounthong was a surgical tech at Emanate Health Queen of the Valley Hospital in West Covina. She was a tiny 58-year-old Laotian woman with a big heart, loved ones said. She worked 12-hour shifts and raced back to her Lakewood home to make dinner for a close friend’s youngest son, who loved her spicy seafood soup. She was a mother, a doting grandmother and a “second mother” to her friend’s kids.

She was also “Case No. 09567,” and she died alone in an overheated hotel room after testing positive for the coronavirus. It would be days before her body was discovered.

Kristina McGuire, an investigator with the Los Angeles County Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner, is one of the health officials tasked with unraveling the mystery of Bounthong’s death — a job that has become far more pressing, and risky, since the pandemic began. My colleague Maria L. La Ganga weaves their stories together in this gripping account.

“Something looks so simple: 58-year-old nurse found unresponsive in her bedroom after testing positive for COVID,” McGuire said. “Automatically, you go, ‘COVID.’ But I don’t know that. … I don’t know anything about her. Everything is an assumption, and you find out the truth later.”

Bone broth blues

It’s no secret that the pandemic has been extremely hard on California restaurants, some of which have been forced to shut their doors for good.

My colleague Nita Lelyveld spent time last week at a little family-owned Pasadena restaurant called Bone Kettle that has survived by pivoting repeatedly as the threats and restrictions have changed. The eatery has shifted to takeout, sold dog toys for its customers’ many canine companions and stocked pandemic-themed greeting cards for the front-line workers who work at nearby hospitals.

More than that, it’s a story of deep resilience for the Tjahyadi family, which owns the restaurant. Younger brother Erwin is the chef; older brother Eric runs the businesses; their father, Tjhing “Simon” Sen, is a jack-of-all-trades at the restaurant. The family came to America in 1995 as part of a wave of ethnically Chinese Indonesians seeking asylum in the U.S. As kids, Erwin and Eric helped their parents clean motel rooms, work at warehouses and recycle cans.

All this is to say: This family has grit. It has a loyal and growing fanbase. And it has largely managed to keep its staff of 20 people working. “As long as we keep fighting, we have a chance,” Eric said.

A pandemic splits a city in two

The Smithfield pork plant in Sioux Falls, S.D., is the site of one of the worst workplace outbreaks in American history. Among its 3,700 workers, 1,294 have become infected — many of them from Sudan, Ethiopia and Bhutan — and four have died during the pandemic.

But while the virus plagued the immigrants who held many of the factory’s jobs, it seemed barely to touch others in this mostly white and largely conservative city of 188,000, my colleague Jaweed Kaleem writes. As much of the nation donned masks, residents of Sioux Falls kept packing rodeos and concerts. “It seemed a strange and surreal tale of two cities,” Kaleem writes.

South Dakota’s coronavirus rates are now among the worst in the world, and its largest city is in some ways a microcosm of the nation, with sharply diverging pandemic experiences and a raging debate tinged with racism.

“We took the virus very seriously,” said Sujeet Urwan, 31, a Smithfield worker who fell ill eight months ago. “But it felt like for a long time that everyone else was not.”

Roll up those sleeves — and get to work

Even though coronavirus vaccines are now entering the arms of front-line workers around California, there’s something a little Pollyannaish about the widely echoed insistence that we are witnessing the “beginning of the end” of the pandemic, columnist Erika D. Smith writes. In truth, she says, “the hardest work is just beginning.” She’s talking about the effort to get vaccine-hesitant people of color to sign up for their shots when the time comes.

The roughly 1 million people who live in South Los Angeles, most of whom are Latino or Black, are at a disproportionate risk of dying of COVID-19. They also have reasons to distrust the medical and healthcare system. Reversing that trend, Smith writes, “requires navigating a maze of past and present institutional failures and processing human fears and distrust.”

That’s what experts at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, a historically Black university in South L.A., aim to do with their intensive outreach in Watts and surrounding communities about COVID-19. (Among other efforts, they set up drop-in, walk-up testing sites, while others have required appointments and cars for drive-through service.) The hope is that when a vaccine is finally widely available, they “will be in a unique position to help persuade the people who need it most to take it,” Smith writes.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

What to do this weekend

Take a virtual vacation. Look for young lions, elephants and other wildlife on livestreamed safaris in South Africa with WILDwatch Live. Or sink into “the most relaxing sounds in the world” courtesy of Unify Cosmos, which allows you to visit tranquil destinations such as the Boundary Waters in Minnesota, Kanha National Park in India and Mermaid Beach in Australia. Subscribe to Escapes for more virtual and California travel ideas.

Watch something great. Head out for a drive-in movie — you can catch “Gremlins” at the Los Angeles Arts Society Drive-in Cinema or “A Christmas Story” at Hollywood Roosevelt Drive-in Theatre. And in his Indie Focus newsletter’s roundup of new movies, Mark Olsen highlights “Funny Boy,” a Canadian film about a young man coming to terms with his gay identity against the backdrop of the Sri Lankan civil war.

Eat something great. Dare to get into the holiday spirit by eating a fruitcake, aka “the world’s first PowerBar,” my colleague Lucas Kwan Peterson writes, offering six spots around the country where you can order one. Or if you need a cocktail to go, grab a mezcal tamarind margarita from Bar Henry, or try something from one of the others recommended by our critics. Check out our 101 list of restaurants, dishes, people and ideas that define how we eat in 2020.

Go online. Here’s The Times’ guide to the internet for when you’re looking for information on self-care, feel like learning something new or interesting, or want to expand your entertainment horizons.The pandemic in pictures

Even as the vaccine rollout offers some hope that there may be an end to the pandemic in 2021, anti-vaccine activists and alt-right groups are teaming up to stage protests in California. It’s a part of an effort that some experts fear could supercharge citizens’ mistrust of government at a crucial moment for public health, my colleague Anita Chabria writes.

“There is this strategic mission creep into other groups that might feel disaffected,” said Richard Carpiano, a professor of public policy and sociology at UC Riverside. Extremist experts have also warned that militant groups protesting election results and lockdowns across the country also see the anti-vaccine movement as a cause that could unite their followers after a presidential transition.

The trend is alarming many experts, and it’s encapsulated by this shot by my colleague Genaro Molina of an anti-lockdown protest that anti-vaccine activists helped organize this month in Stockton. You can read the full story here.

Resources

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask. Here’s how to do it right.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.