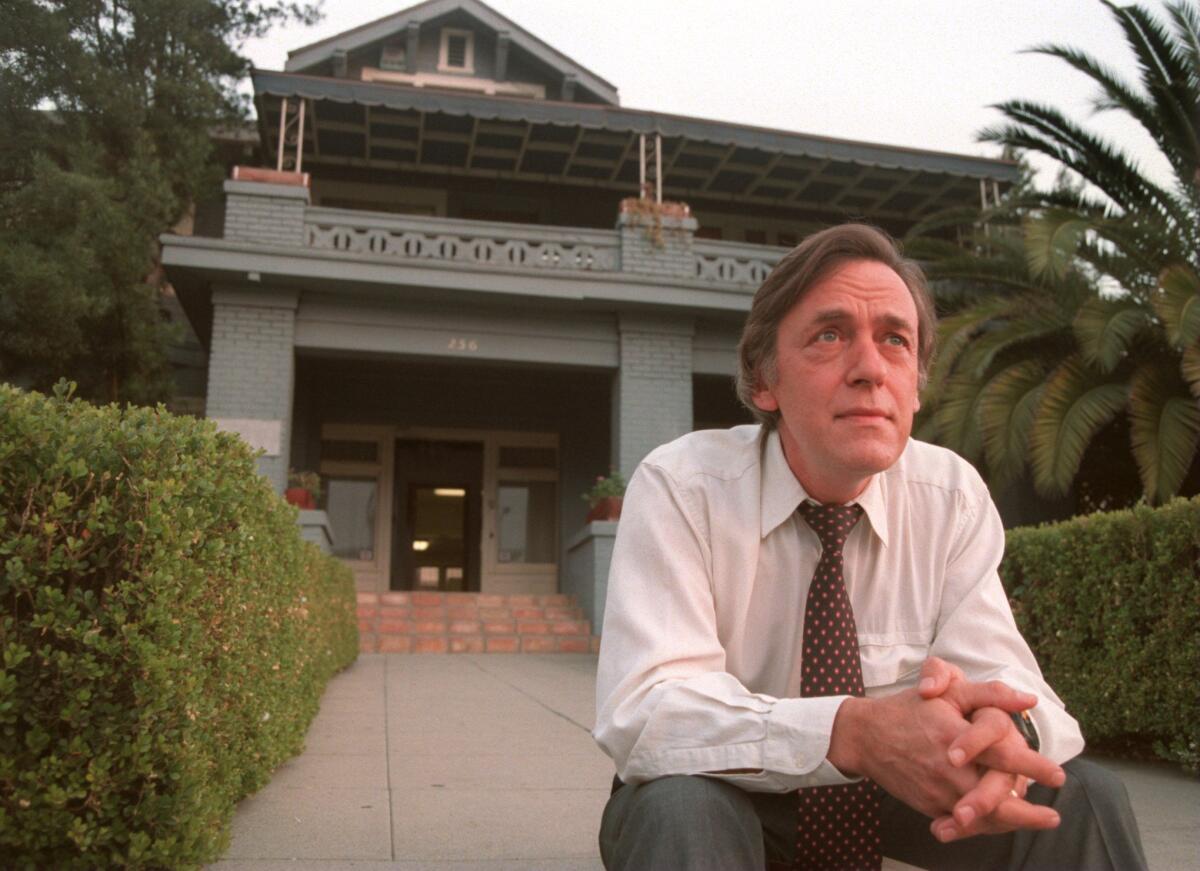

Peter Schey, longtime Los Angeles champion of immigrant rights, dead at 77

WASHINGTON — Peter Schey, who championed the rights of immigrants over decades as a Los Angeles attorney and led the case that overturned Proposition 187, the controversial initiative to deny government services to undocumented immigrants, died of complications from lymphoma Tuesday at age 77.

Schey, the founder and executive director of the Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law, led class-action cases on behalf of immigrants involving access to public education, medical care and the welfare of unaccompanied minors.

Born in South Africa to parents who fled Germany — his father was a Jewish anti-Nazi agitator — Schey moved to San Francisco as a teenager with his parents when they packed up during apartheid. He attended UC Berkeley and the California Western School of Law in San Diego.

After obtaining his law degree, Schey represented low-income immigrants at the Legal Aid Society of San Diego. In 1978, he founded the first national support center dedicated to protecting immigrant rights, now known as the National Immigration Law Center.

He was lead counsel in Plyler vs. Doe, a landmark 1982 Supreme Court decision which found that states cannot deny undocumented children access to free public education.

“I feel moved when I encounter people who are suffering in some way that seems unnecessary, that seems to result only from the actions of some bureaucratic official or agency,” Schey later told The Times.

A decade later, in Flores vs. Reno, Schey fought for the establishment of minimum national standards for the treatment of detained immigrant children and limits to how long they can be held. The case remains under the supervision of U.S. District Judge Dolly Gee in the Central District of California.

A federal judge in Los Angeles will appoint an independent auditor to oversee the treatment of children in immigrant detention facilities.

The Trump administration tried to ax the Flores settlement agreement, which allows attorneys to periodically inspect detention facilities where children are held, but the move was blocked in federal court.

Schey’s group filed a scathing report in 2018 with testimony from more than 200 parents and children held in California, Texas and other states who described cramped cells, cold or frozen food and a lack of basic hygiene products.

Schey also led the case against California’s 1994 law, Proposition 187, that sought to deny medical care, social services and education to people suspected of lacking lawful immigration status. League of United Latin American Citizens vs. Wilson stopped the law from ever taking effect, and mediation several years later formally voided it.

Prop. 187 was seen as a turning point in California politics, mobilizing Latinos to register to vote and contributing to a significant increase in Democrats winning local and state elections. U.S. Sen. Alex Padilla is one of several California leaders who say their political awakening came from their activism against Prop. 187.

“From successfully helping fend off California’s Proposition 187 to staunchly advocating for the rights of immigrant children and families in government custody, Peter was a champion for immigrants,” Padilla said in a statement. “An immigrant himself from South Africa, Peter helped ensure equal access to public education for immigrant children and was a trailblazer for the constitutional rights of immigrants. His legacy will live on in communities across California and our country.”

In recent years, Schey became a controversial figure among immigrant advocates. As COVID-19 spread through detention facilities in 2020, he came under fire from fellow attorneys who disagreed with his position that detained parents could choose between remaining detained with their children or allowing their children to be released without them. The other attorneys, from RAICES Texas and Aldea — The People’s Justice Center, called the decision “sanctioned family separation.”

And The Times reported in 2019 that Casa Libre, a shelter he started for homeless migrant youth near MacArthur Park, failed to meet standards for state-licensed group homes and neglected the children in its care.

“With Casa Libre, he just got in over his head,” said Schey’s ex-wife and good friend Melinda Bird. “At the end we finally persuaded him to find another group to run it.”

Father Richard Estrada, who had worked with Schey since his days as a chaplain for Spanish speakers at a Los Angeles juvenile hall, said he disagreed with Schey’s approach to certain things, such as the shelter. Still, he said, Schey was an inspirational, brave man.

“We lost an icon of human rights,” Estrada said Wednesday.

Schey was diagnosed with cancer late last year, according to his friends and colleagues. Carlos Holguin, who had worked alongside him since 1977, said Schey went through chemotherapy and his health had improved until recent days.

Holguin said that while the public knows Schey for his legal wins, friends knew him for smaller acts of kindness, such as the times he fed and cleaned up a homeless man who hung around outside their office.

Schey was complicated too, Holguin said — singularly driven, a workaholic.

“I think I’m the only one who managed to work with him for anything more than two or three years,” he said, chuckling. “None of us is perfect. But I never questioned the goodness of his heart.”

While he’s known for his work on immigrant rights, Schey also took on legal projects on other issues. Last year, he went to Tanzania — his first time back to Africa since his family left — to advocate to the United Nations on behalf of Maasai herders displaced by big-game hunters. He caught COVID-19 upon his return in October. When the sickness didn’t go away, he finally saw a doctor.

Bird said she was with him in his final days as friends and former clients cycled in and out of the UCLA hospital room.

Also in the room was a 2-by-3-foot photo of their late daughter, Alexis, who died 10 years ago at age 28. Her death was the greatest tragedy of his life, Bird said.

Before finding out the cancer had returned, against everyone’s advice, Schey had started working again. He had also made time to have fun, attending a Sly and the Family Stone tribute band show with Bird a few weeks ago.

“When he first got sick in October, with all these tubes coming out of him, he said to me: ‘I have been so lucky,’” Bird recalled. “He kept that attitude for the whole six months.”

Schey is survived by a sister, Nicky Arden, and two children, Michael and Alyssa Schey.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.