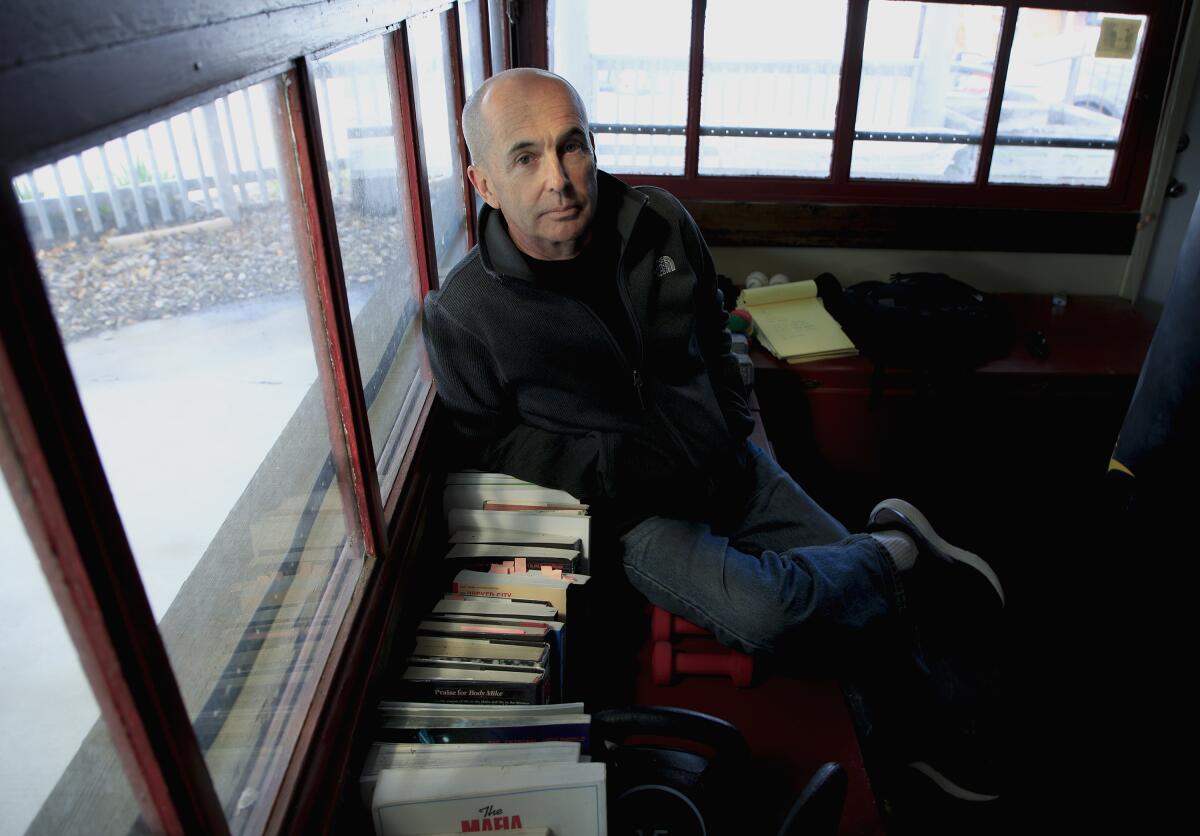

Novelist Don Winslow is out to save America from Donald Trump — and an existential crisis

A hard rain passed over Dana Point. Seals swam beneath broken clouds. A chill settled in amid the scent of cut bait, but no boats were sailing for open water. “You know,” said Don Winslow, nodding toward the marina and the sea beyond, “they used to drop marijuana bales out there and boats would go get them.”

Winslow is intimate with illicit patterns in pretty places. He knows the coves, the surf boys, the sins past the breakwater. The bruises up the coast. One of America’s best crime novelists, Winslow, an Irish Catholic kid who found fortune later in life, can, when the politics strike him, evince the heart of a fighter. One need only mention Fox News or any number of Donald Trump acolytes.

“The Lauren Boeberts and Tucker Carlsons of the world are the classic schoolyard bullies,” he says. “They talk tough, but the second you punch them in the nose, they go running and crying to teacher.”

Winslow has become an incensed political activist in recent years. His barrage of more than 106,000 tweets to nearly 1 million followers reverberate through social media. His Don Winslow Films — a partnership with agent and screenwriter Shane Salerno — produces videos that attack Trump and conservatives under titles like: “The Truth about Ivanka,” “7 Years No Indictment” and “Revolving Door of Crazy Republicans.” They have been viewed more than 250 million times.

Last year, Winslow surprised the literary world by announcing he was giving up writing novels to concentrate full time on activism. The news arrived around the publication of “City on Fire”, the tale of a mob war in Providence, R.I. The book is the first in a trilogy; “City of Dreams’’ is out April 18 and “City in Ruins” will be published in 2024. The final two were finished during the pandemic, and Winslow says they are the last of his fiction, which began in 1991 with “A Cool Breeze on the Underground” and has spanned more than 20 novels, including a string of bestsellers.

“The times we’ve been living in have demanded a different response from me than what I could do in a novel,” he said. “I wanted in the fight. I didn’t want to be writing a fiction obituary of America losing democracy.” He didn’t relish the prospect that someone might say, ‘’He’s written a wonderful book about the death of our culture. Oh, great. Thank you very much.”

Winslow’s America isn’t broken, but it’s dangerously cracked.

Sitting the other day at a coffee shop in Dana Point, he said, “We’re two camps and we’re exhausted. Four years of chaos from the worst administration in the history of this country bar none. The sheer criminality. Then COVID. Then the insurrection.” A lot of people, he continued, want to say,”‘Let’s get past it. It’s over.’ The problem is, it’s not over. You have active insurrectionists in the House.”

When Trump was indicted last week on charges related to an alleged hush money payment to film star Stormy Daniels, Winslow tweeted: “More than anything else, I hope this is just the first indictment of Donald Trump. I want to see the disgraced ex-President forced to fight multiple indictments in different locations - state and federal - at the same time.”

Despite a penchant for activism, one wonders, though, is his quitting novels like Tom Brady quitting football?

“Never say never,” said Winslow, who wrote a blurb for this writer’s latest book. “No one believes me,” he added. “But, yes, I’m done.”

::

Winslow speaks with the quiet fierceness he picked up as a boy in South Kingstown, R.I., where newspapers carried Boston Red Sox scores and stories of the latest mob hits around New England. “I grew up,” he said, “playing pond hockey with fishermen’s kids.”

He’s a Kennedy Democrat and the son of a librarian and a sailor. He arrived in California decades ago, driving PCH, living in hotels, writing fiction and working as a private investigator. He wrote his 1997 novel “The Death and Life of Bobby Z” on train trips back and forth from Dana Point to Los Angeles.

Bundled in a leather jacket, he watched rain turn to hail and the skies clear only to darken again. Women with yoga mats ran for cover. “Born to Be Wild” played on the radio. Winslow warmed his hands on a cup of black coffee. He spoke of his days as a photographic safari guide in Africa, directing Shakespeare in England and how his great-great-grandfather fought for the North in the Civil War, a point of pride.

“I’ve been stopped on the road by people yelling at me. I’ve had pickup trucks pull up beside me and [someone] yell out the window. ‘We don’t like what you said on Twitter,’” he said.

“We get threats all the time,” he continued. “On this last book tour, we got messages, ‘Hey Donny, you’ll never leave Florida. Say goodbye to your friends.’ Most of those people are physical as well as moral cowards. I’m 69 years old. What are they going to do to me?”

American novelists over the years have worked to confront and distill the nation’s wants, moods and politics. Its vast, complicated heart. Mark Twain, Toni Morrison, John Dos Passos, Ralph Ellison, Don DeLillo and, more recently, Jonathan Franzen and Louise Erdrich, have explored our desires, cultures, prejudices and troubles. Gary Shteyngart and Salman Rushdie have delved into the age of Trump. And some, like novelist Norman Mailer, who was at his best when filing real life dispatches from the political revolts and antiwar protests of the 1960s, worked to define the times.

Winslow has long been attuned to the nation’s consciousness and how it plays out at home and across borders, especially in his novels on the drug trade. He has driven across the country more than a dozen times, mapping highways, studying vernaculars. Scottish novelist Martin Patience recently told NPR that Winslow writes “about the big, difficult issues of our time. And I think he does it in such an engaging fashion without dumbing down.”

Winslow’s activism accelerated as Trump rose in the polls ahead of the 2016 election. “Very early on when he mocked a disabled reporter, I thought, ‘My God, that’s a horrible person,’ ” he said. “I called Donald Trump a fascist in 2015, and the critique I got from people was, ‘You’re out of your mind. You’re a fantasist, a radical. You’re crazy.’ ”

But, Winslow added, “Fast forward to Jan. 6. Hello. Donald Trump is Mussolini with worse hair and less a command of English.”

Such assessments barb Winslow’s tweets. His attacks on Trump and his family; politicians like Marjorie Taylor Greene, whom he describes as a “shock attention tool”; the Supreme Court; Liz Cheney, whom he says duped Democrats; and others, including those who demonize Latino migrants, unspool through his fevered missives on Republicans. An equivocator, he is not, saying, “2020 was an existential moment in American history. We could have lost democracy.”

Much of his aim is not to win over conservatives but to keep liberals vigilant. In the lead-up to the 2022 midterm elections, Winslow warned against complacency and said Republicans could win the House. As that was happening, he tweeted: “They were no doom tweets. They were the truth you did not want to hear.”

Democrats and the Biden administration attract his ire as well. He criticized the Democrat-controlled Jan. 6 committee early in its investigation for not subpoenaing key players in the insurrection. He accused Atty. Gen. Merrick Garland of a “cowardly act” by appointing a special counsel to investigate Trump, rather ordering the Justice Department to prosecute the former president. And he posted a searing video attack on Sen. Joe Manchin III‘s (D-W.Va.) ties to the coal industry under the title “West Virginia abused and suckered for 40 years.”

He thinks his party is too soft for these bare-knuckled times.

“They continually bring plastic spoons to a gunfight,” said Winslow, whose son, Thomas, worked for President Biden and is now with the Democratic National Committee. “We’ve become very genteel, haven’t we? We don’t want to go in the alley. We don’t want to go in the trenches.”

“It’s a condescension“— and it’s a real problem, he said. “It’s something Trump tapped into.”

In 2020, Winslow and novelist Stephen King offered to donate $200,000 to St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital if then-White House Press Secretary Stephanie Grisham would hold a formal news conference, which the Trump administration had not done for months. The challenge went viral and drew applause from the left. She saw it as a publicity stunt.

Grisham, who never held a briefing as press secretary, told CNN that if the authors “have $200,000 to play with, why not just help children because it’s a good thing to do? Donations to charity should never come with strings attached.”

Winslow responded with a tweet: “First, we both regularly donate to charity. . .Stop evading, Stephanie. Let’s try again: Why have you not held any White House press briefings for over 300 days? What are you afraid of?”

One of Winslow’s posts has raised questions about free speech in the age of Twitter. He was sued for defamation after a 2020 tweet calling a doctor “the butcher” for performing “illegal hysterectomies” on women at a federal immigration detention center in Georgia. The Times reported that at least 19 women alleged they were medically abused by Dr. Mahendra Amin. A Senate investigation last year found that the doctor appeared to have practiced “excessive, invasive, and often unnecessary gynecological procedures.”

Amin, who has also sued NBCUniversal Media, denied wrongdoing. Winslow filed a motion to dismiss the case under California’s anti-SLAPP law. He argued that his tweet — coming in the context of his other posts linking to news reports — was opinion without malice and protected under free speech. A district court ruled in Amin’s favor, saying the doctor is not a public official and Twitter is not a “public journal” with the same privileges as a newspaper. Winslow has appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit, where more than two dozen media organizations filed a brief in January supporting his motion.

::

A good portion of Winslow’s writing life has reflected America back on itself, notably his drug war trilogy that ended in 2019 with “The Border,” a 700-plus-page world of DEA agents, cartels, a young Guatemalan migrant, a New York heroin addict, and a supporting cast of vicious souls carrying out cruel deeds. The books, which are being made into a TV series by FX Networks, grew out of Winslow’s extensive research into U.S. drug policy over the decades.

“Don’s political activism is a natural evolution for him,” said novelist Lou Berney. “He’s one of those rare writers who has a mastery of the facts and the art. They collide into a greater truth. He’s like Prince. He can play a bunch of different instruments expertly.”

Winslow’s new trilogy about New England mobsters, specifically Danny Ryan, an engaging Irish American dock worker who gets drawn into a mafia war, was inspired in part by the ancient Greeks. In the late 1990s, Winslow decided that he was “ill-read except in crime fiction.” He spent seven years reading the classics, including the “Iliad,” Homer’s paean to the Trojan War, whose characters and adventures reminded Winslow of gangsters.

“I thought I grew up with these guys,” he said. “All the themes we treat in crime fiction have already been done. We just put fedoras on them. What happens to them [men in the “Iliad”] after the Trojan War is pure noir. Agamemnon’s wife kills him in the bathtub.”

Set in 1980s Providence, “City on Fire,” with its early allusion to a Helen of Troy-type emerging from the surf, sends Ryan into a maelstrom. “City of Dreams” dispatches him on a journey, much like Aeneas, who wandered for years after the Trojan War. Ryan heads across America to Hollywood where he falls for a woman he probably should avoid. The prose is lean and sly, peppered in grit. To paraphrase one of Winslow’s heroes, Elmore Leonard, the key is to cut the stuff no one will read.

“Every word,” said Winslow, “has to pay the rent or do the dishes.”

And keep things brisk: “If I’m at A, I don’t have to go through B and C to get to D.”

The same is true for one of his provocative political tweets or one of his videos titled “How to Convict Trump.” It’s about villains and saints and immediacy. He said that he and Salerno, founder of The Story Factory, an entertainment company, and co-writer on the “Avatar” sequels, “talked about how can we be practically useful. To have an impact, not just to be jawing on social media but to really be effective and to talk to people where they are and where they live. Not to be condescending. To be tough.”

Mary Trump has praised Winslow’s activism. The former president’s niece and frequent critic told Winslow on her podcast “The Mary Trump Show”: “You’ve been doing some of the best work out there in terms of helping people understand what we’re facing,” she said. “Helping people personalize the threats.”

Winslow said he expects the battle for the country to last years. America is in no mood for reconciliation. Blame is the game, and accountability is rare.

The sky above Dana Point cleared, but the edges north and west were dark. Winslow finished his coffee and put on a ball cap. He walked along the docks toward the bridge, where, in “The Death and Life of Bobby Z”, bodies piled up in the harbor and a getaway boat sailed beyond the surf break for open water.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.