What do Trump’s indictments mean? Answers to questions about the former president’s legal troubles

The federal judge assigned to the election fraud case against former President Trump stands out as one of the toughest punishers of rioters who stormed the U.S. Capitol. Judge Tanya Chutkan often has handed down prison sentences in Jan. 6, 2021, riot cases that are harsher than what Justice Department prosecutors recommended.

Hush-money payments allegedly disguised as legal fees. Sensitive federal documents stashed at Mar-a-Lago. An alleged conspiracy to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election. A coordinated effort to pressure Georgia officials to change their vote count.

Four times this year, grand juries have charged former President Trump with committing election-related crimes — in the most recent instance, he was accused of leading a criminal enterprise involving his lawyers, aides, campaign staff and supporters. Three of his co-defendants have pleaded guilty and agreed to testify for the prosecution. None of his predecessors has ever been indicted, let alone charged with multiple criminal acts.

Meanwhile, a New York state judge in Manhattan has ruled that Trump and his eponymous company deceived their business partners by assigning values to Trump’s assets that were far above their actual worth. The ruling came in a civil lawsuit filed by New York Atty. Gen. Letitia James against Trump and top executives in his real estate business, including his two eldest sons, accusing them of fraudulently inflating Trump’s net worth on official financial filings. The point of the scheme, the lawsuit alleges, was to help Trump obtain loans and insurance policies with better terms.

Trump and his attorneys blasted the ruling by state Supreme Court Judge Arthur Engoron, calling it politically motivated and contrary to the facts. The former president is appealing, and a state appeals judge has temporarily suspended Engoron’s order dissolving some of Trump’s businesses.

James filed her lawsuit last September. Trump’s legal troubles intensified this March, when a grand jury in Manhattan accused him of violating a state law against falsifying business records in connection with hush money paid to a porn star. That case is still pending, and Trump has pleaded not guilty.

On June 8, a federal grand jury in south Florida indicted Trump on 37 felony charges related to his handling of classified documents after he left the White House. He pleaded not guilty to all charges. Then on July 27, three more charges related to the sensitive documents were added in a superseding indictment.

The documents charges resulted from a probe led by Jack Smith, a special counsel appointed by U.S. Atty. Gen. Merrick Garland. On Aug. 1, a second investigation led by Smith produced another federal indictment, this one accusing Trump of committing four federal crimes in his efforts to prevent Joe Biden from taking office as president.

On Aug. 14, a Fulton County, Ga., grand jury handed down a 41-count indictment focused on alleged efforts by Trump to claim the electoral votes that Biden narrowly won in Georgia, including Trump’s request that state election officials “find 11,780 votes” for him — enough to beat Biden by one vote. Georgia was one of a handful of swing states that tipped the election in Biden’s favor.

Here’s a rundown of what’s happening, starting with the most recent developments and continuing back to the first indictment.

Former President Trump is indicted in Georgia over his efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election there, his fourth indictment this year.

What does the New York ruling against Trump mean?

Engoron decided a major factual question in the attorney general’s favor even before her lawsuit goes to trial. By holding that the values Trump assigned to his assets were fraudulent, the judge limited the trial to the question of what penalties, if any, to assess against Trump and the other defendants.

Engoron also imposed one of the sanctions that James had sought, revoking the certificates required to operate a number of Trump’s businesses in New York. An appeals court judge suspended that sanction but allowed the trial of James’ remaining claims to begin Oct. 2.

The trial is ongoing in Manhattan.

What are the latest criminal charges against Trump?

The Georgia indictment’s main charge is that Trump, 18 co-defendants and at least 30 unindicted co-conspirators violated Georgia’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations law through actions that started the day after election day in November 2020 and continued until mid-September 2022.

The indictment alleges that the group “engaged in various related criminal activities including, but not limited to, false statements and writings, impersonating a public officer, forgery, filing false documents, influencing witnesses, computer theft, computer trespass, computer invasion of privacy, conspiracy to defraud the state, acts involving theft, and perjury.”

Central to the charges are accusations that members of the group:

- lied to state lawmakers, state officials and courts about election fraud;

- “corruptly solicited” then-Vice President Mike Pence and U.S. Justice Department officials to support the false claim of fraud;

- gathered supporters to cast false electoral college votes for Trump, which they transmitted to various officials in Washington;

- broke into secure voting equipment and stole sensitive data

- harassed a county election worker;

- lied to investigators and filed false documents to cover up their crimes.

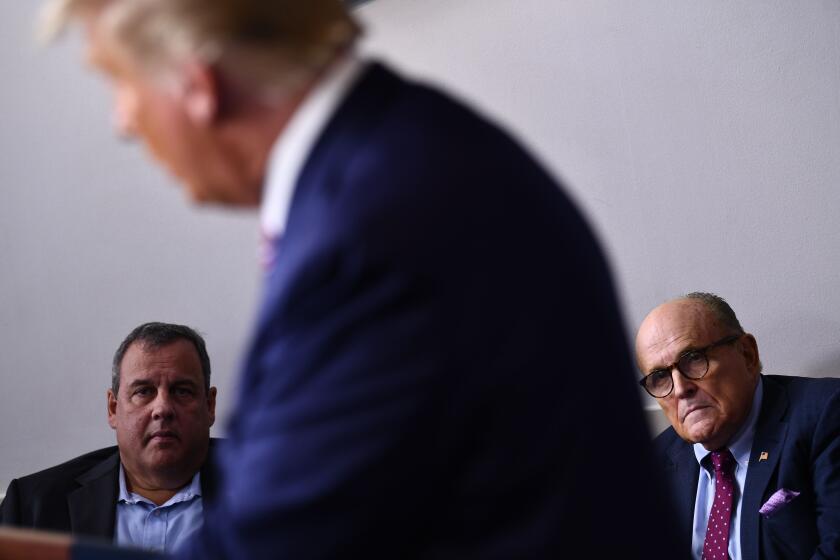

Alongside Trump, the indictment names a number of figures who played prominent roles in the former president’s effort to hold onto office, including lawyers John Eastman, Rudolph W. Giuliani, Jenna Ellis and Sidney Powell; former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows; and former Assistant U.S. Atty. Gen. Jeffrey Clark.

Trump faces 13 of the 41 counts, including several conspiracy charges related to the false slate of electors in Georgia. The rest of the counts involve other defendants.

Trump’s campaign responded to the charges in much the same way the former president had to previous indictments: by accusing the prosecutor, in this case Democratic Fulton County Dist. Atty. Fani Willis, of being a “rabid partisan” trying to interfere in the 2024 election.

“They are taking away President Trump’s First Amendment right to free speech, and the right to challenge a rigged and stolen election that the Democrats do all the time,” the campaign said in a statement shortly before the indictment was made public.

Read the full indictment of former President Trump in Fulton County, Ga., related to the attempt to overturn the 2020 election results.

What happens next in the Georgia case?

Three of Trump’s co-defendants — lawyers Sidney Powell, a highly visible proponent of Trump’s claims of election fraud; Kenneth Chesebro, a leader in the effort to replace duly chosen Biden electors with Trump electors, and Scott Hall, a bail bondsman accused of helping the Trump campaign tamper with voting equipment and ballots after the election — have accepted plea deals. In exchange for their guilty pleas, they will pay fines and spend years on probation. They’ll also be expected to testify in the other defendants’ trials.

Powell and Chesebro had been scheduled to go to trial Monday. The presiding judge in the case, Fulton County Superior Court Judge Scott McAfee, denied Willis’ request to try Trump and the other 16 defendants then as well.

Five of those defendants — Meadows, Clark and three Georgia Republicans accused of being fake electors for Trump — sought to remove their cases to federal court, arguing that the charges stemmed from their actions as federal officials. But a federal judge denied their requests, saying that Meadows and Clark weren’t acting in their official capacity when helping Trump contest the election results, and the three Georgians weren’t federal officials to begin with.

A New York judge rejected a similar motion in the case brought against Trump in state court there.

If the former president’s case is moved to the federal court for the Northern District of Georgia, it would bring in a new presiding judge — potentially one appointed by Trump. It would also open the jury pool to residents of more counties that voted for Trump; the former president won less than 30% of the vote in Fulton County.

What about the cases Smith is pursuing?

In a 45-page indictment released Aug. 1, a grand jury in Washington accused Trump of working with at least six unnamed co-conspirators — five lawyers and a political consultant — to try to retain the presidency after his loss to Biden. The accusations will be familiar to anyone who followed the hearings held by the House Jan. 6 select committee, which urged the Justice Department to bring charges against the former president.

The indictment accuses the conspirators of knowingly spreading false and “crazy” assertions about election fraud; urging officials in seven states to reverse election results under false pretenses; creating slates of fake electors to obstruct Congress’ certification of the electoral college vote; and trying to persuade Pence to ratify the fraudulent elector scheme.

Each count carries a potential prison term if Trump is convicted, ranging from a maximum of five years to a maximum of 20 years.

Trump denounced the charges on his social network, Truth Social, saying the Biden administration was the one engaged in election interference. He also said he “did nothing wrong [and] was advised by many lawyers.” He has pleaded not guilty.

The indictment alleges that Trump pursued discounting legitimate votes and subverting the 2020 presidential election results through three criminal conspiracies.

Prior to these charges, a federal grand jury in south Florida accused Trump in June of 38 felonies related to the sensitive government records he retained at his Mar-a-Lago resort post presidency. These included top-secret and other classified records that discussed nuclear capabilities, potential U.S. vulnerabilities to attack and possible retaliatory strikes in response to such an attack, the indictment alleges.

The grand jury expanded the indictment in late July to include one additional charge of willfully retaining national defense information and two new charges of obstruction of justice.

The first of the new charges relates to a meeting in July 2021 at Trump’s golf club in Bedminster, N.J., involving Trump, two aides and two people helping Trump’s former chief of staff, Mark Meadows, write his memoirs. At the meeting, Trump allegedly showed off a top-secret document discussing plans for an attack on a foreign country.

The two obstruction charges — which were also brought against Trump’s personal aide and co-defendant, Walt Nauta, along with a new defendant, Mar-a-Lago employee Carlos De Oliveira — accuse the men of trying to erase surveillance video from Mar-a-Lago that Smith’s investigators were seeking. The investigators were looking for evidence that Trump had tried to hide some of the government documents sought by the National Archives and Records Administration.

Trump has pleaded not guilty to all of these charges as well.

Former President Trump is facing additional charges on new allegations in the Justice Department’s prosecution over classified documents in Florida.

What happens next in the federal cases?

Courtroom skirmishes have already begun in both of the federal indictments ahead of trial. Key issues are when those trials will be scheduled and how much Trump can talk about them in the meantime.

On the documents case, U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon denied Trump’s request to postpone the trial until after the 2024 election — which, if he won, would allow him to try to pardon himself or force the Justice Department to dismiss the case. Instead, the trial is scheduled to begin May 20 in Fort Pierce, Fla., where Cannon presides.

Between now and then, the defense is expected to bring multiple motions challenging the indictment and the evidence Smith gathered. The two sides are also fighting over whether Trump must travel to a secure facility in order to discuss the classified documents in the case with his attorneys, or if a secure facility can be built in Mar-a-Lago.

On the indictment in Washington, U.S. District Judge Tanya S. Chutkan set the trial to begin March 4 — much closer to Smith’s proposed trial date of Jan. 2 than to Trump’s request to be tried in 2026. According to Politico reporter Kyle Cheney, Chutkan said Trump’s campaign had no bearing on the trial schedule.

Chutkan has also settled a second key issue: how much latitude Trump will have to talk about the evidence that prosecutors have gathered (about 11.6 million pages, according to CBS News) on social media and elsewhere. The judge issued an order that restricts him from publicly discussing any documents that prosecutors deem sensitive.

Judge Tanya Chutkan said she will not consider the 2024 campaign in making decisions during the trial tied to alleged efforts to overturn the 2020 election.

Why was Trump hit with records charges when others weren’t?

After the FBI recovered documents from Trump, President Biden and Pence also disclosed that they had found classified papers in their possession. What distinguishes Trump’s case from theirs, legal observers say, is that Biden and Pence have worked with federal officials to return documents, while Trump is accused of obstructing the government’s efforts to retrieve them.

The Justice Department issued a statement this month saying it wouldn’t charge Pence. The special prosecutor’s investigation into the Biden documents is ongoing.

The FBI investigated former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in 2015 and 2016 for using a private email server at her home, which the agency found had handled 110 pieces of information that should have been restricted to the department’s classified email system. Then-FBI Director James B. Comey criticized Clinton for “careless” handling of classified material but said there was no evidence that she’d intended to violate the law.

Critics of the investigation say that Clinton’s staff shouldn’t have been allowed to destroy some 30,000 emails before they were reviewed by the FBI. Clinton’s team said at the time that the emails were personal, not related to State Department business.

The Justice Department has prosecuted and continues to prosecute lower-level government employees for document crimes under the Espionage Act. Under the Trump administration, for example, five current or former government employees were charged under the act for allegedly leaking national defense information to the press.

Is the Biden administration prosecuting the president’s top political opponent?

Polls show that, by a wide margin, Trump is the leading Republican candidate to face Biden in 2024. But while the administration is ultimately responsible for the Justice Department, it wasn’t involved in the decision to bring charges against the former president.

The investigations and prosecutions are the work of a special counsel, so there’s a measure of independence from the White House. Although Smith was picked by Garland, a Biden appointee, federal regulations prevented the attorney general from influencing Smith’s decision to prosecute.

The former president pleaded not guilty to federal charges in Florida. It’s the latest episode of a half-century of legal trouble and journalistic malfeasance.

Doesn’t the Presidential Records Act absolve Trump?

The former president claims that the federal Presidential Records Act gives him the authority to take papers back to Mar-a-Lago. “There was no crime, except for what the DOJ and FBI have been doing against me for years,” Trump wrote on Truth Social.

The National Archives and Records Administration, which is the official custodian of White House records, responded that the act does no such thing.

“The Presidential Records Act (PRA) requires the President to separate personal documents from Presidential records before leaving office,” NARA said in a statement June 9. “The PRA makes clear that, upon the conclusion of the President’s term in office, NARA assumes responsibility for the custody, control, preservation of, and access to the records of a President.... There is no history, practice, or provision in law for presidents to take official records with them when they leave office to sort through, such as for a two-year period as described in some reports.”

What happens next in the records case?

U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon has set a trial date for May 20, 2024 — after all but a handful of states have held their presidential primaries. The trial will be held in federal court in Fort Pierce, Fla., where Cannon is based.

Prosecutors wanted to start the trial in December, but Trump’s lawyers sought to delay it until after the election. Cannon split the difference, considering the legal requirement for a speedy trial and the time Trump’s team needs to review the vast collection of documents involved in the case.

The case is currently in the phase where prosecutors disclose the evidence they’ve gathered to Trump’s lawyers, and the two sides can begin making procedural motions, such as a motion to dismiss the case.

The Florida jurist could impede the Department of Justice’s effort to hold the former president accountable for his handling of classified records in a few ways.

Why did New York City prosecutors investigate Trump?

Because Trump was accused of violating state law while in New York in 2016, when he was running for president.

One of Trump’s former attorneys, Michael Cohen, admitted in federal court that he paid $130,000 to porn actor Stormy Daniels shortly before the 2016 election to keep her from talking about an affair she says she had with Trump. Cohen also admitted in court papers that Trump’s New York City-based real estate business reimbursed him the next year but disguised the payments as a large monthly retainer.

Trump has denied having an affair with Daniels and paying her to stay quiet. One of his current lawyers has accused her of extorting money from him. The former president declined an invitation to testify before the Manhattan grand jury.

What are the charges there?

Trump is accused of 34 separate violations of a New York law against falsifying business records to conceal another crime, a felony punishable by up to four years in state prison and a $5,000 fine. The charges relate to 11 checks written to Cohen in 2017, along with the invoices and account entries associated with them.

In a statement of facts about the case, Manhattan Dist. Atty. Alvin Bragg Jr. alleged that the payments were part of a scheme led by Trump “that hid damaging information from the voting public during the 2016 presidential election.” As part of that scheme, the statement alleges, Trump and “Lawyer A” — i.e., Cohen — made payments either to buy the silence of or bury accusations made by a former Trump Tower doorman in 2015 and two unnamed women. The conspiracy also involved the editor in chief of the National Enquirer, who agreed to pay $30,000 to the doorman and $150,000 to one of the women not to discuss their accusations that Trump had engaged in extramarital affairs, the statement alleges.

That woman appears to be Karen McDougal, a former Playboy Playmate of the Year who sued the parent company of the National Enquirer in 2018 to be released from the contract that barred her from discussing the affair she says she had with Trump. As with Daniels, Trump denies having an affair with McDougal.

The charges in the indictment relate only to the payment Cohen has admitted making to the second woman, Daniels. The statement alleges that the Trump Organization paid Cohen back through monthly checks in 2017 that it characterized as a legal retainer, even though “there was no such retainer agreement” and Cohen rendered no services that year. Trump signed nine of the checks himself, the statement alleges; the other two were signed by one of Trump’s sons and the Trump Organization’s chief financial officer.

New York requires defendants to appear in person to be booked, which is why Trump flew to the city Monday for the arraignment Tuesday. Accompanied by Secret Service agents, he turned himself in at a Manhattan courthouse early Tuesday afternoon and reportedly was booked, but no mugshot was taken.

What happens next in that case?

Trump is free on bail, with his trial scheduled to begin March 24. Defense motions will be due by the end of August. Rulings on those motions aren’t due until early in 2024.

Is there a statute of limitations on Trump’s alleged N.Y. crimes?

There is, but the time limit was extended because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, the clock stops when the defendant spends an extended amount of time away from New York; some legal analysts say that this would apply to Trump because of the four years he spent in the White House.

Does this have anything to do with the 2020 election?

No. These accusations relate to the 2016 election, which Trump won.

It’s foolish to predict the impact if Trump is indicted. But there’s reason to believe things have changed and his scot-free days may be over.

Would being arrested affect Trump’s ability to serve as president?

No. Even if he were convicted and sent to prison, Trump could serve as president — the U.S. Constitution requires only that a president be at least 35 years old, a “natural born citizen” and a resident of the U.S. for at least 14 years.

Any criminal charges against Trump would certainly affect his campaign. And if he were imprisoned, winning the 2024 election wouldn’t automatically cut short his sentence.

It’s unclear how he would be able to discharge the duties of his office from a prison cell, which means the 25th Amendment could come into play. Under that, a president can hand off his duties temporarily to the vice president if he cannot perform them himself, or the duties can be taken from him if the vice president and a majority of top executive branch officials vote to do so.

Once in office, Trump could not be removed unless the House impeached him (for a third time) and the Senate convicted him (for the first time).

By the way, the Constitution doesn’t say whether the “high crimes and misdemeanors” required for impeachment can occur before a president takes office. In fact, it leaves it to Congress to decide what acts constitute impeachable offenses and when they must have occurred.

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.