California outlawed the all-white-male boardroom. That move is reshaping corporate America

WASHINGTON — When Dr. Maria Rivas joined the board of a medical tech firm called Medidata a few years ago, she was a novelty: The company had never had a woman in that role.

Medidata was no outlier. Rivas, chief medical officer at Merck, had impressive credentials when she breached the rarefied world of boardrooms in 2018, but much of corporate America wasn’t looking for candidates like her. “It is unfortunately comfortable for humans to go with people who look like they do,” Rivas said.

For hundreds of public companies, that meant filling boards exclusively from their networks of familiar faces — typically white men.

Then California outlawed the all-white-male boardroom.

The state’s requirements that publicly traded corporations diversify their boardrooms were ridiculed as quixotic by conservative columnists and some corporate chieftains. The courts are still threatening to erase the quotas, the first of which were signed into law in 2018.

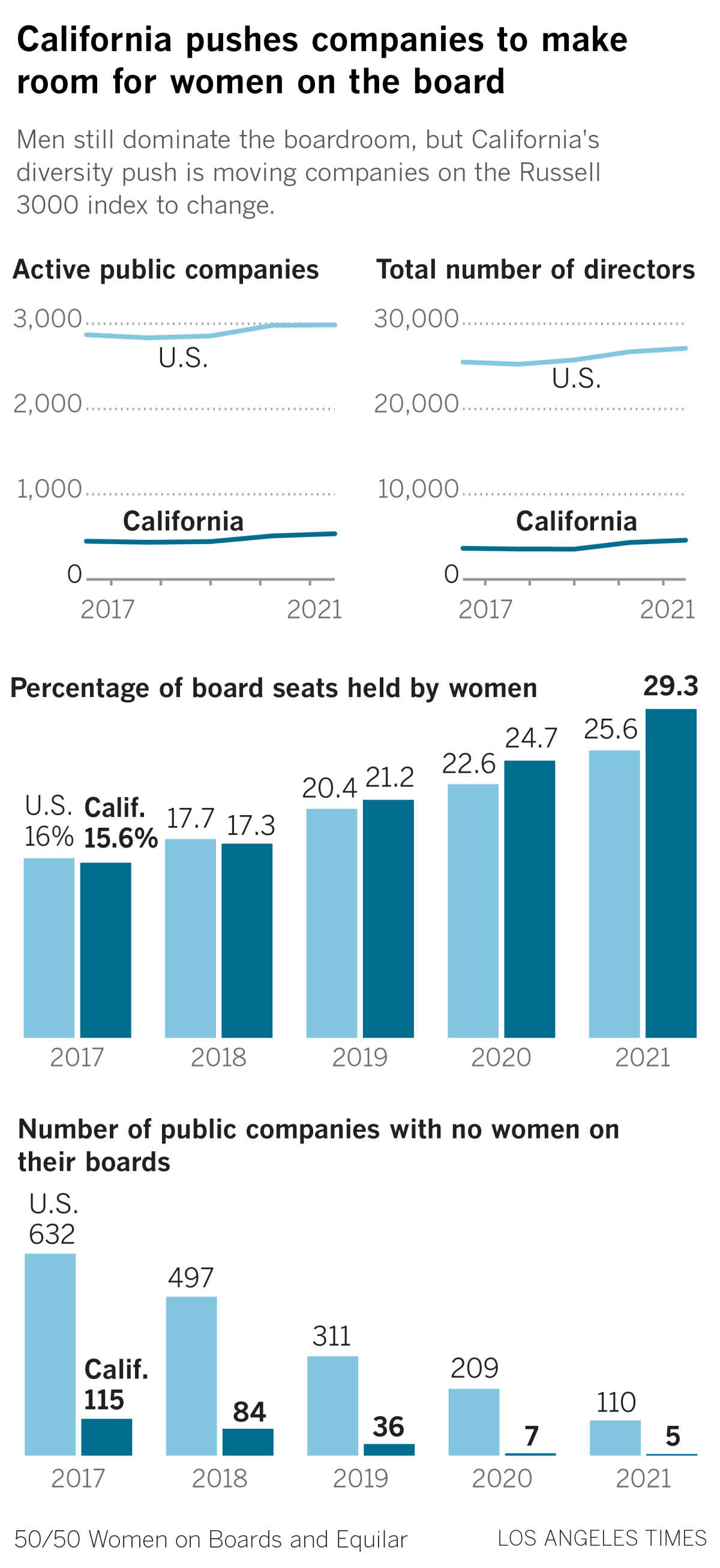

But California is having the last laugh. Even as the mandates on women and people of color have become a flashpoint in the culture wars, companies across the country are embracing California’s boardroom diversity directives. Women now control more than a quarter of corporate board seats nationwide — 50% more than they did before the 2018 California law requiring women on boards was passed. Companies are also scrambling to recruit people of color as other diversity mandates begin to take effect.

The state’s crusade is reshaping the corporate boardroom, an institution that for decades refused to evolve — and which guides the direction, culture and financial stewardship of public companies. Even as the courts signal the new rules could collapse legally, the requirements that every public company headquartered in the state have women and members of traditionally underrepresented groups on its board are driving hundreds of companies to make room at the top — and inspiring other states and federal regulators to join California’s push.

No state has had a bigger impact on the direction of the United States than California, a prolific incubator and exporter of outside-the-box policies and ideas. This occasional series examines what that has meant for the state and the country, and how far Washington is willing to go to spread California’s agenda as the state’s own struggles threaten its standing as the nation’s think tank.

“The ripple effect has gone across the nation,” said Betsy Berkhemer-Credaire, chief executive of the Los Angeles-based advocacy group 50/50 Women on Boards. She predicts that within a decade, “it will be quite an anachronism to remember when corporations had all-white-male boards.”

Recently joining California’s crusade is an even more influential force in the business world. The Nasdaq exchange is requiring nearly all of the more than 3,000 companies listed on it to have on their boards at least one woman and one person of color or person who identifies as LGBTQ — or explain to shareholders why they don’t.

Federal regulators gave that diversity rule a green light in August, over the objection of a dozen Republican senators. The rule extends even to firms headquartered abroad, though they are given more time to diversify.

The lawmakers — 11 men plus Sen. Cynthia Lummis of Wyoming — warned in a letter to the Securities and Exchange Commission that the regulation would hurt the economy by pushing a social agenda.

Yet the companies those lawmakers say they are seeking to protect are hardly sounding the same alarm. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce threw its support behind the Nasdaq diversity plan and a similar proposal in Congress for a national rule.

“We have seen California make a lot of progress,” said Democratic U.S. Sen. Alex Padilla, who in his previous job as California secretary of state was charged with ensuring the 647 public companies headquartered there followed the law. “It is what makes sense for the nation, as well.”

Analysts predict the New York Stock Exchange will soon unveil its own blueprint to push board diversity that is modeled after California’s aspirations. Goldman Sachs announced this year that it won’t take a company public in the U.S. unless at least two of its board members are not straight white men. Investment giant BlackRock expects companies it aligns with to have at least two women on their board.

In the name of climate action, California pushed the world toward electric cars. But building enough of them is creating its own environmental crises.

The rapid shift is creating demand for executives such as Darnell Strom, who heads the culture and leadership division at United Talent Agency. The 40-year-old veteran agent whose job puts him at the intersection of entertainment, media and politics had earlier figured an ossified corporate culture left boardrooms closed to candidates like him.

“The makeup of them were people who do not look like me,” said Strom, a Black millennial. “We all felt it was this exclusive club we did not have access to.”

Now, Strom gets regular calls from board recruiters. He recently became the first person of color to join the board at Wynn Resorts. The Las Vegas company had earlier added three prominent women to its board in an overhaul driven by the fallout from sexual misconduct allegations against former Chief Executive Steve Wynn.

The business case for diversifying a board, Strom said, is obvious. Companies are confronting cultural, security and public health shifts that demand they widen their expertise at the top, and the old guard of board directors isn’t equipped to meet the moment.

Wynn, for example, is an operation that needs to tap into fast-changing social trends. Yet Strom is the rare director on its board with a background in entertainment and media. Other companies are consumed with cybersecurity or pandemic safety concerns, yet have nobody on their boards to take a lead on those issues.

“If you were recruiting for a board 20 years ago, you weren’t thinking about cybersecurity or digital marketing or global supply chain,” said Tracey Doi, the chief financial officer and group vice president for Toyota Motor North America, and also a board member at two public companies — City National Bank and Quest Diagnostics — that have several women in their boardrooms.

“This past 18 months is a critical juncture for companies to step back and ask: Are we operating on a model that is sustainable coming out of this pandemic?” Doi said. “Are we embracing a different mindset for how we will serve customers within their communities?”

The inspiration for California’s diversity push came from Europe, where several countries had imposed mandates. Norway more than a decade ago required that at least 40% of corporate board positions be filled by women. France, Germany, Italy and other European nations later created their own quota systems. France this year went even further, directing companies to fill at least 30% of all their top executive posts with women by 2027. The European rules tend to be mostly gender-focused, as opposed to American targets that also aim to boost racial and ethnic diversity.

Researchers are conflicted on whether a more diverse board helps increase profits, but findings that it does from heavyweight firms such as Morgan Stanley and McKinsey & Co. are solidifying support around the push in the U.S.

The Pacific Legal Foundation, the conservative group taking a lead in resisting the California rules, has not been able to entice a single public company to join its court fight.

President Trump tried to marginalize California. He failed. Now, with Joe Biden and Democrats taking power, no state is more influential in setting a policy agenda.

“There were not any corporations that we could find that were willing to stick their necks out as a plaintiff,” said Anastasia Boden, the lead attorney on the case. “Nobody wanted to be seen as opposing this law, because they were afraid that they would be perceived as anti-woman.”

The plaintiff the Pacific Legal Foundation has instead is Creighton Meland Jr., a retired Chicago lawyer who owns shares in OSI Systems, a California-based security and medical equipment firm.

The foundation’s argument that the law forces shareholders such as Meland to discriminate in favor of women when they choose board directors is getting traction in court. The U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, finding that Meland’s claims have merit, reversed a lower federal court’s dismissal of the suit.

“This law gets equality exactly wrong,” Boden said. “It requires the very thing that we’re trying to get rid of in society: doling out benefits and burdens on the basis of the characteristics that we are born into. This is perpetuating a myth that women can’t make it to the corporate board without help.”

The lawsuit argues companies were already moving toward gender balance on their boards without quotas. That point is in dispute.

“People who say this was happening anyway are completely wrong,” said Doug Chia, a fellow at the Center for Corporate Law and Governance at Rutgers Law School in New Jersey. “The needle had not been moving at all before California acted.”

Former California Gov. Jerry Brown described the law as legally shaky when he signed it, but he said the state had no choice but to push ahead. The #MeToo era was well underway, and Brown wrote in his signing statement that many companies and leaders “are not getting the message.”

Brown signed the 2018 law over the objections of the California Chamber of Commerce, which led a coalition of 30 organizations, including the state’s major restaurant, grocery and wine grape grower trade groups, in fighting gender quotas for corporate boards. Nationally, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce still opposes hard quotas like California’s, even as it supports the Nasdaq blueprint and the proposal in Congress, which would force companies that fail to diversify to explain themselves to shareholders but do not impose penalties.

By the time Brown signed the quotas into law, state lawmakers had already tried more gentle means, urging companies to bring more women into their boardrooms with a nonbinding legislative resolution in 2013. Companies ignored it.

“We weren’t able to get companies there using reason and data,” said Hannah-Beth Jackson, the former state senator from Santa Barbara who championed the mandates in the Legislature. “So we required they get there. California has a history of leading the nation in a variety of areas, and this was a first.”

That law, Senate Bill 826, required companies to have at least one woman on their board by 2019, and as many as three women — depending on the size of the company — by the end of this year.

There were at least 115 California public companies that did not have a single woman on their board in 2017. Now there are only five — or just 1% of the state’s firms on the Russell 3000 index. Yet most companies still have work to do.

More than half of California’s public companies need to add women to their boards by the end of this year. Meeting the state’s stepped-up requirements demands that at least 335 more women take seats on company boards in the next few months. And the state is still a long way from achieving gender balance on company boards: Only 8% of the state’s public companies have gotten there.

Another state law, Assembly Bill 979, signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom last fall, requires California-based public companies to have on their boards by the end of this year at least one person of color or person who identifies as gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender, and as many as three such board members by the end of 2022. While Black representation on boards has grown amid the nation’s reckoning on race, people who are not white or straight still hold only 18.4% of the board seats in the top 1,000 public companies nationwide, according to data released in August by executive data firm Equilar.

Washington state followed California’s lead early this year, passing its own requirement that corporate boards include women. Lawmakers in Hawaii, Massachusetts, Michigan and New Jersey are considering similar measures. Several other states, meanwhile, have recently passed laws that call out companies failing to diversify their boards, by requiring they disclose board demographic data to shareholders.

The shift has touched off a recruiting frenzy among companies, with many creating board seats specifically so they could add positions for women.

“These laws make a huge difference,” said Rivas, a Cuban immigrant who grew up in Puerto Rico.

Medidata is a New York firm, but she said California’s move to outlaw all-male boards played into the effort companies like it are making to diversify. New York, for its part, recently started requiring companies to disclose to shareholders whether they are making any progress toward gender balance on their boards.

Rivas has since joined the board of Cooper Cos., a much larger medical device firm based in California, at which she became the first person of color to serve.

“We need more laws like California’s across all the states,” Rivas said. “It will result in companies that are more in touch with our society.”

Climate credits sold to California polluters bring billions to landowners. But scientists ask if that’s an environmental investment or a Ponzi scheme.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.