SAN DIEGO — The precious cargo on the ship docked in San Diego Bay was strikingly small for a vessel built to drag oil rigs out to sea. Machines tethered to this hulking ship had plucked rocks the size of a child’s fist from the ocean floor thousands of miles into the Pacific.

The mission was delicate and controversial — with broad implications for the planet.

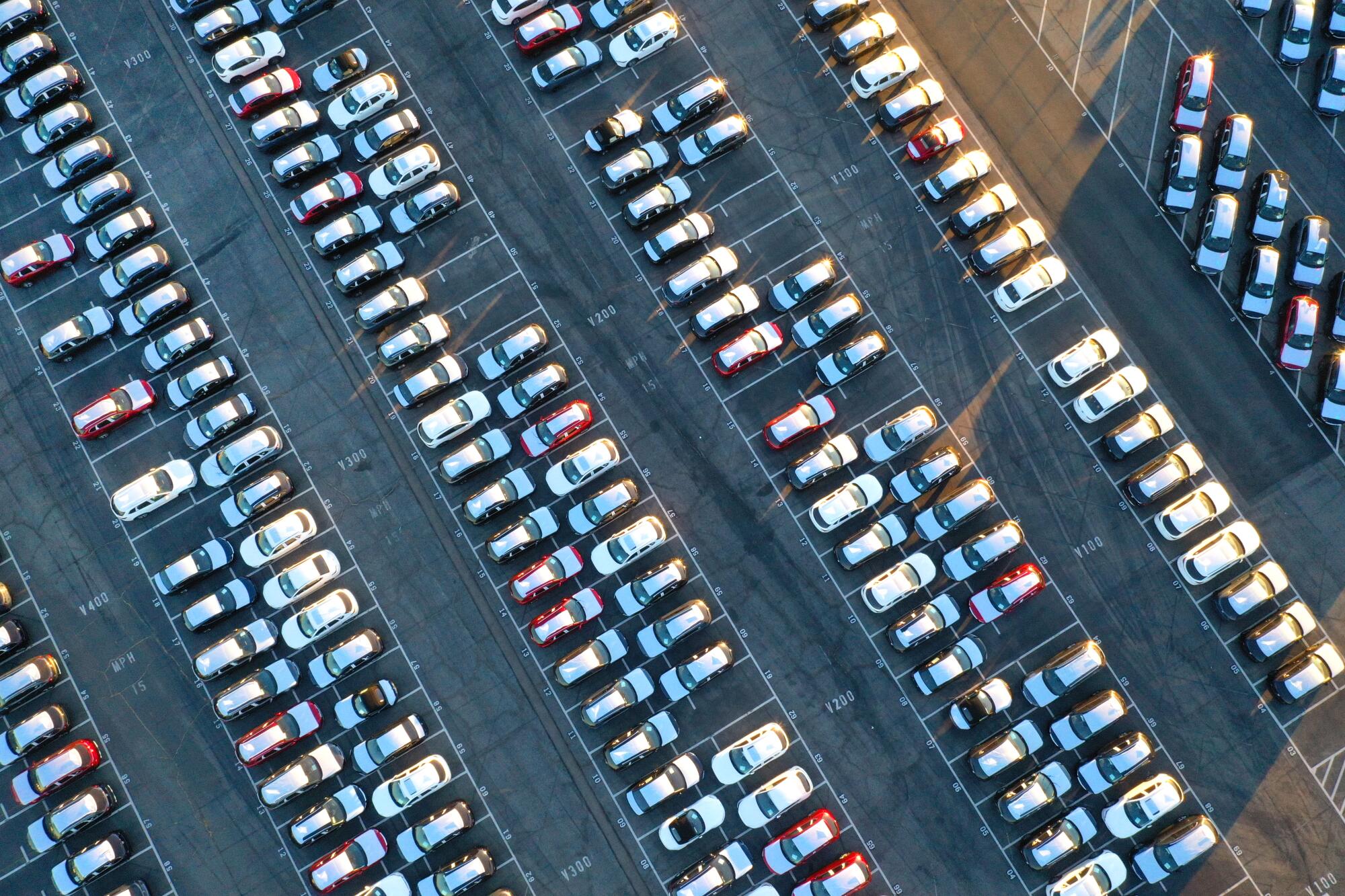

Investors are betting tens of millions of dollars that these black nodules packed with metals used in electric car batteries are the ticket for the United States to recapture supremacy over the green economy — and to keep up with a global transportation revolution started by California.

Alongside his docked ship, Gerard Barron, chief executive of the Metals Co., held in his hand one of the nodules he argues can help save the planet. “We have to be bold and we have to be prepared to look at new frontiers,” he said. “Climate change isn’t something that’s waiting around for us to figure it out.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

The urgency with which his company and a few others are moving to start scraping the seabed for these materials alarms oceanographers and advocates, who warn they are literally in uncharted waters. Much is unknown about life on the deep sea floor, and vacuuming swaths of it clean threatens to have unintended and far-reaching consequences.

The drama playing out in the deep sea is just one act in a fast unfolding, ethically challenging and economically complex debate that stretches around the world, from the cobalt mines of Congo to the corridors of the Biden White House to fragile desert habitats throughout the West where vast deposits of lithium lay beneath the ground.

ABOUT THIS SERIES

No state has had a bigger impact on the direction of the United States than California, a prolific incubator and exporter of outside-the-box policies and ideas. This occasional series examines what that has meant for the state and the country, and how far Washington is willing to go to spread California’s agenda as the state’s own struggles threaten its standing as the nation’s think tank.

The state of California is inexorably intertwined in this drama. Not just because extraction companies are aggressively surveying the state’s landscapes for opportunities to mine and process the materials. But because California is leading the drive toward electric cars.

No state has exported more policy innovations — including on climate, equality, the economy — than California, a trend accelerating under the Biden administration. The state relishes its role as the nation’s think tank, though the course it charts for the country has, at times, veered in unanticipated directions.

“The ocean is the place on the planet where we know least about what species exist and how they function,” Douglas McCauley, a marine science professor at UC Santa Barbara, said of plans to scrape the seafloor. “This is like opening a Pandora’s box.... We’re concerned this won’t do much good for climate change, but it will do irreversible harm to the ocean.”

The sprint to supply automakers with heavy-duty lithium batteries is propelled by climate-conscious countries like the United States that aspire to abandon gas-powered cars and SUVs. They are racing to secure the materials needed to go electric, and the Biden administration is under pressure to fast-track mammoth extraction projects that threaten to unleash their own environmental fallout.

In far-flung patches of the ocean floor, at Native American ancestral sites, and on some of the most pristine federal lands, extraction and mining companies are branding themselves stewards of sustainability, warning the planet will suffer if digging and scraping are delayed. All the prospecting is giving pause to some of the environmental groups championing climate action, as they assess whether the sacrifice needed to curb warming is being shared fairly.

“A lot of people see sagebrush and they think…what’s the value in this?” says environmental activist Max Wilbert. “ You have to be willing to wait and be patient because at this time of the day, all the wildlife, all the action, they’re hiding there in the shade.” (Video by Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

“Front-line communities affected by mining are asking the rest of us: What sacrifice are you making?” said John Hadder, executive director of Great Basin Resource Watch, a Nevada group fighting a proposed massive lithium mine at Thacker Pass, near the Oregon border. “You are asking us to have our community and environment permanently disrupted. All you are doing is maybe driving a different car.”

California ‘created these markets’

California began plotting in 1990 to force car manufacturers to make zero- emission vehicles. The cars were so undesired when they began rolling off assembly lines by the early 2010s that they were tagged “compliance cars” — built and sold only to comply with California mandates.

Yet California, the global trendsetter on cutting tailpipe emissions, kept pushing — until electric cars became not only functional, but stylish. Next year, 500 electric vehicle models will be sold worldwide.

“California’s policies created these markets,” said Matt Petersen, president of the Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator.

By 2035, California will ban the sale of gas-powered cars in an effort to address climate change and push drivers toward electric vehicles. But that means we’ll need more raw materials to build electric car batteries – like lithium, which is typically sourced and refined abroad – until now.

The state’s crusade — including a ban on sales of new combustion engine cars and SUVs by 2035 — has analysts projecting a surge in demand for the cobalt, lithium, manganese, nickel and other materials used to build electric car batteries. Need for these materials could soar by 600% globally over the next two decades, according to the International Energy Agency.

Electric cars account for 1.7 million vehicle sales annually worldwide, and that number could soar to 8.5 million by 2025, Bloomberg New Energy Finance projects. The transformation is happening quickest in Europe and China — where more than 20% of cars sold will be electric by 2025. California aims to hit similar numbers by then, even as the rest of the U.S. moves more slowly.

The success of electric cars is a point of pride for not just California, but the Biden administration, which is trying to meet the commitments in the Paris climate accord. But it is also a point of panic. The administration warns the transition threatens to leave the nation vulnerable to the whims of countries that control supply chains. President Biden in June ordered the Departments of Energy and the Interior to help industry bolster mining and processing of battery materials.

China controls most of the market for the raw-material refining needed for the batteries and dominates component manufacturing; industry analysts warn the monopolization presents not only an economic risk, but also a national security one.

The cost of finding new sources for raw materials and loosening China’s grip on the supply chains is large. That much is clear in Thacker Pass, a windswept pocket of northern Nevada where the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe has for centuries hunted sage grouse, collected plants for medicine, and gathered for ceremonies. It is also the largest reserve of lithium in the United States.

A million batteries, a massive mine

A mining permit pushed through in the last week of the Trump administration allows the Canadian company Lithium Americas Corp. to produce enough lithium carbonate annually to supply nearly a million electric car batteries. The mine pit alone would disrupt more than 1,100 acres, and the whole operation — on land leased from the federal government — would cover roughly six times that. Up to 5,800 tons of sulfuric acid would be used daily to leach lithium from the earth dug out of a 300-foot deep mine pit.

Tribal members and some ranchers are fighting the plans, alarmed by details in the environmental impact assessment: The operation would generate hundreds of millions of cubic yards of mining waste and lower the water table in this high desert region by churning through 3,200 gallons per minute. Arsenic contamination of the water under the mine pit could endure 300 years.

Pronghorn antelope roam amid the sagebrush that spreads for miles in Thacker Pass, nestled between the Montana and Double H mountain ranges. The sound of fierce winds is interrupted by the occasional call of a brown eagle or screech of a hawk. The Lithium Americas blueprint would transform the pass into a hub of industrial activity.

“Our Indigenous people have been here so long. This is our homeland,” said Daranda Hinkey, a tribal member and secretary of People of Red Mountain, a group of Indigenous people fighting the mine. “We know every mountain in our language. We don’t get to leave. This is our origin story.”

Hinkey, 23, studied environmental policy at Southern Oregon University, examining transportation emissions and climate change and the green economy. “But we did not talk about things like this,” she said. “We never talked about, ‘Look at how much they are extracting.’ We talked about sustainability, but this does not seem sustainable.”

Many of the tribal members who gathered for a daylong ceremony on the pass recently shared stories of the fallout from the area’s long history with mercury, gold and silver mining. The trade-offs for the jobs mining brought to Nevada’s Humboldt County, they said, were cancer clusters, water and air contamination and broken promises to clean up the land.

Now tribal members are working with environmental activists, many of whom are living in a protest camp set up the day the Thacker Pass permit was approved in January.

“They would come in here with explosives, with heavy earthmoving equipment, and they would begin by scraping off everything that we can see here,” Max Wilbert, a leader of the protest camp, said as he gestured toward sagebrush stretching to the horizon.

The mine permit was approved so quickly that the opposition coalesced only afterward. Tribal leaders initially raised no objections, and Lithium Americas says 40 members have already asked about jobs. But a new tribal government installed in the winter looked more closely at the environmental impacts and scrapped a nonbinding engagement agreement with the mining company.

Lithium Americas frames the project as a different kind of mine: less destructive, more connected to the community. Chief Executive Jonathan Evans says the company is seeking partners in the U.S. to turn the lithium into battery components.

“I don’t see how you can fight climate change without batteries,” Evans said from the firm’s office in Reno. “We really believe in what we are doing.”

He said that the company would backfill and restore the mining pit as it digs and that it aims to train and hire any interested tribal members. “This isn’t your grandparents’ mining,” Evans said.

The green pitch initially impressed rancher Edward Bartell, who leases 50,000 acres of federal land for his cattle alongside the proposed mine site. Now he regards it as greenwashing.

“I actually was kind of excited about it,” Bartell said, as he walked along the arid landscape where his cattle graze on native grasses and brush. “My view has changed dramatically.” Once he dug into the details, Bartell said, he concluded the mine would leave his ranch irreparably parched and polluted. He is suing to stop it.

The tension at Thacker Pass does not bode well for the Biden administration’s ambitious plans to shore up electric vehicle supply chains. Thacker Pass was initially poised to be a kind of demonstration project, highlighting how the U.S. is equipped to reassert itself in mining and critical mineral processing — sectors it long ago ceded to nations with less stringent environmental rules.

The United States’ one working lithium mine, in Silver Peak, Nev., produces only enough lithium to build 100,000 electric vehicle batteries a year. There are 17 million cars sold annually in the U.S. alone, and Biden’s plan is for most of them to be electric within 15 years.

Extraction companies are exploring several more potential sites in Nevada and looking to dig in Arkansas, North Carolina and other states. A coalition of Native Americans and environmental groups is fighting to keep lithium developers from building a mine in California’s Panamint Valley, at the edge of Death Valley National Park.

California’s ‘Lithium Valley’

In California’s Salton Sea region, a collection of community leaders, environmental advocates and companies is trying to forge a path toward more eco-friendly production of lithium.

They hope to extract lithium from the brine generated by geothermal power plants. It was tried a decade ago in the Imperial Valley but proved too costly. The coming boom in the lithium market, however, has three companies back at it.

The state has set up a commission to guide development of what’s been branded “Lithium Valley.” It is a sensitive assignment in a region where farmworkers and Indigenous people have long suffered from toxic air created by agricultural runoff that became airborne when the sea’s water level dropped.

“All the conditions here are prime for this type of innovation,” said Luis Olmedo, a longtime environmental justice advocate in the Imperial Valley who sits on the Lithium Valley Commission. “But we’ve learned our lessons. People who care and are involved in this conversation are going to be much wiser on how they protect the resources of Imperial Valley.”

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Lithium is just one challenge. There are several other elements needed to build electric vehicle batteries that auto industry players warn could become scarce if the U.S. does not step up production. Plans for massive copper mines in Minnesota’s Boundary Waters region and at Oak Flat in Arizona are drawing fierce local opposition.

Environmentalists and scholars question how much of this race to mine is driven by the public interest and how much by extraction and other industry executives exploiting climate talking points.

“I would push back against the narrative that there needs to be this massive expansion of new minerals,” said Payal Sampat, mining program director at the watchdog group Earthworks. Some activists point to the abundance of raw materials being mined around the world, and argue the focus of the U.S. should be on improving conditions in those operations and making the necessary investments and agreements to ensure supply is not cut off.

They note battery technology is advancing fast — as is recycling technology — and the materials that firms are clamoring to mine could be obsolete by the time they start tearing up the earth.

Scraping the seabed

The debate over how much damage should be inflicted on the planet to save it may be most intense far out to sea. The Metals Co. and others plan within three years to start vacuuming patches of the deep ocean floor for nodules that contain many of the metals that go into electric car batteries along with lithium. Many scientists say the timeline is dangerously irresponsible.

More than 500 scientists from 44 nations recently signed a petition against the mining, warning there are too many unknowns. It could destroy entire ecosystems, the scientists say, leading to potentially devastating consequences for the broader ocean. BMW, Volvo, Google and Samsung are all pledging — for now, at least — not to use materials mined from the deep sea floor.

The mining is not allowed under international law. The International Seabed Authority is only permitting the Metals Co. and select other operations to collect polymetallic nodules and conduct scientific research in a few dozen experimentation zones as the authority considers commercial-scale harvesting.

“Every single part of this nodule I hold in my hand is usable material,” said Barron, the company CEO, as he showcased one of the rocks from the giant ship that had just returned from its six-week expedition in a remote region of the Pacific called the Clarion Clipperton Zone.

“It’s like having an [electric vehicle] battery in a rock, and they lie on the ocean floor unattached,” Barron said. “Compare that to the alternative on land, where we’re having to rip down our forests, our trees, our plants, dig up our soils, to get to metal. That has enormous unintended consequences.”

The company estimates that nodules on just a small fraction of the ocean floor could supply the nickel, cobalt, copper and manganese needed to build 280 million electric vehicle batteries — enough to power every car and SUV on the road in America. It’s a potent marketing point in the context of the environmental injustice unfolding at land-based mining operations.

The Metals Co. points as an example to cobalt, a key component of the batteries. More than half the world’s supply comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo, where children are exploited for cheap labor. Amnesty International estimates some 40,000 children are working in the country’s cobalt mines.

“A person buying an electric vehicle is probably not that aware of the fact that children are mining for their batteries in the DRC,” said Bramley Murton, a marine geology professor at the National Oceanography Center in Southampton, England. Murton cautions against ruling out industrial-scale harvesting of ocean nodules.

“Unless the whole of civilization is going back to the Dark Ages and using horses and carts, we need these raw materials,” he said. “We have to get them somewhere.”

It’s a complicated endeavor for many of the scientists on board the Metals Co. ship, who are not necessarily bullish on the firm’s plans to start scraping the seabed by 2024. But there are few other opportunities for ocean scientists to collect samples and conduct research that far and deep in the ocean. It is a costly undertaking. The Metals Co., known as DeepGreen prior to an ongoing merger with deep-pocketed investors, is spending $100 million on an environmental impact study it hopes to use to convince the seabed authority that its plans are sound.

“I am not for mining and I am not against it,” said Andrew K. Sweetman, a professor of earth, marine science and technology at Heriot-Watt University in Scotland who was on the most recent Metals Co. expedition. Sweetman was overseeing collection of samples from a bulky high-tech machine that drops more than two miles into the sea and might best be described as the underwater cousin to the InSight lander that NASA sent to Mars.

The contraption is enabling scientists to learn how organisms function in a corner of the Earth that is scarcely better understood than much of outer space.

“I’m getting the best environmental data that we can,” Sweetman said. The seabed authority will ultimately use that data to make its ruling. “At least I know at that point that they have the best information that they can have to make that decision.”

Others are less confident.

The seabed authority is being forced to cram its decision-making into a two-year time frame after Nauru — one of 167 member nations — recently triggered a clause in the authority’s charter allowing it to fast-track a decision. Nauru’s partnership with the Metals Co. presents the prospect of a financial windfall for the tiny Pacific island nation.

“Bureaucracy can get in the way of progress,” said Barron, the company CEO. “Climate change is an existential crisis. We do not have the luxury of sitting around for decades to dwell on these impacts.”

Yet many scientists say there are any number of deep-sea life forms that are too little known for debate to even begin. They warn that the plumes kicked up by harvesting machines could destroy ecosystems, damage the seafood industry and kill off critical organisms that could take lifetimes to come back, if they ever do.

When one deep-sea creature made its debut to humankind five years ago, the charismatic, milky white octopus quickly became a social media sensation. Its resemblance to a playful cartoon ghost earned the marine mollusk the name Casper.

The prospects for Casper are not great if the demand for electric vehicle batteries sparks a frenzy of deep sea harvesting. The octopus lays its eggs on sponges attached to the nodules metal companies are so eager to scrape from the ocean floor.

“We don’t know what is down there,” said Andy Whitmore, an officer at the Deep Sea Mining Campaign, which is pushing for a ban on seabed mining. “There has not been enough exploration and understanding of what life there is, how it is linked to higher life forms and what happens if you remove the nodules sustaining these organisms.”

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.