Column: Newsom recall effort underscores California’s status as a place apart

If there is one thing that California produces in abundance — apart from movie stars, avocados and Silicon Valley billionaires — it’s superlatives.

The world’s fifth-largest economy. The biggest population of any state. The finest wines, oldest redwoods, most destructive wildfires.

And then there’s the recent tendency to place the governor on a chopping block, even before his term ends.

No other state has exhibited such eagerness to skip the normal voting process and seize an early opportunity to vent. In the whole history of the United States, there have been just four gubernatorial recall elections. California now accounts for half of them, spaced less than 20 years apart.

The state may have the most trigger-happy election system in America.

A new poll from the Public Policy Institute of California found that 58% of likely voters surveyed oppose removing Newsom from office compared to 39% who support recalling the governor.

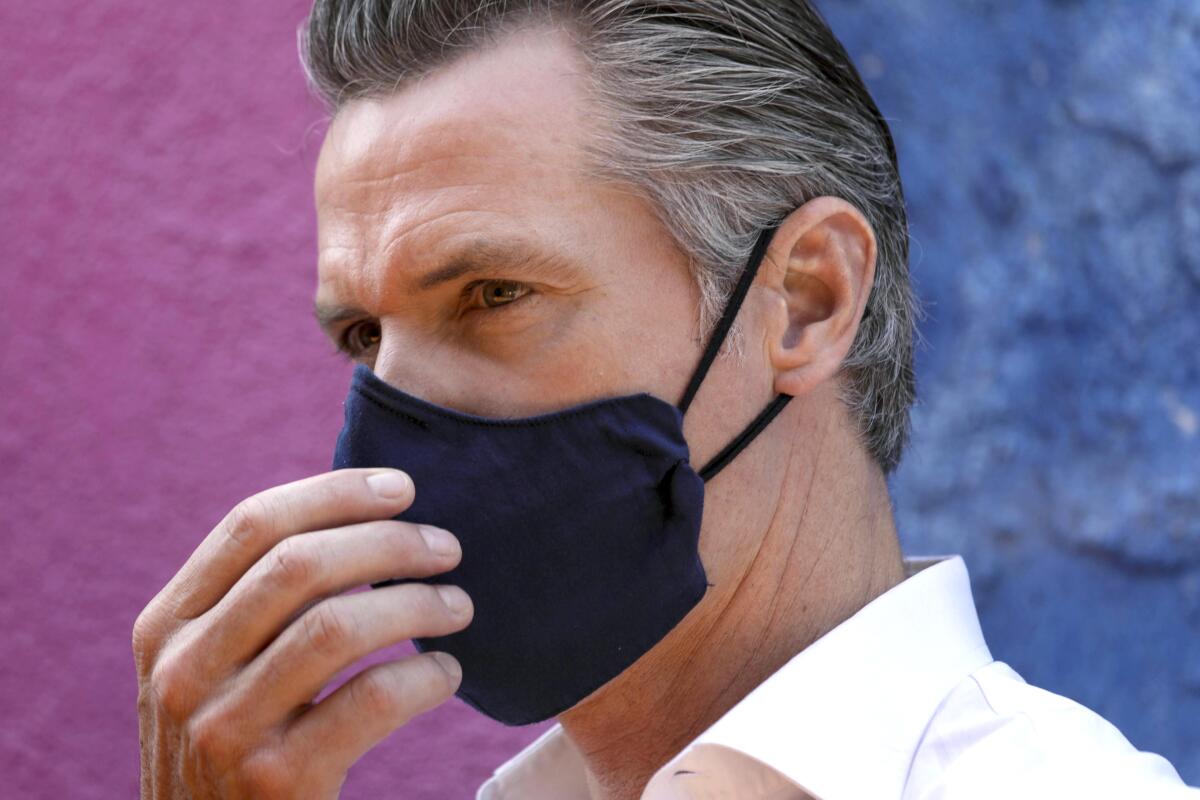

Gavin Newsom won the governorship in November 2018 in the kind of landslide most politicians only dream of. Today he’s scrapping for political survival, trying to avoid joining California’s Gray Davis, a fellow Democrat ousted in 2003, and North Dakota’s Lynn Frazier, a Republican removed in 1921, as the only governors ever turned out of office in a recall.

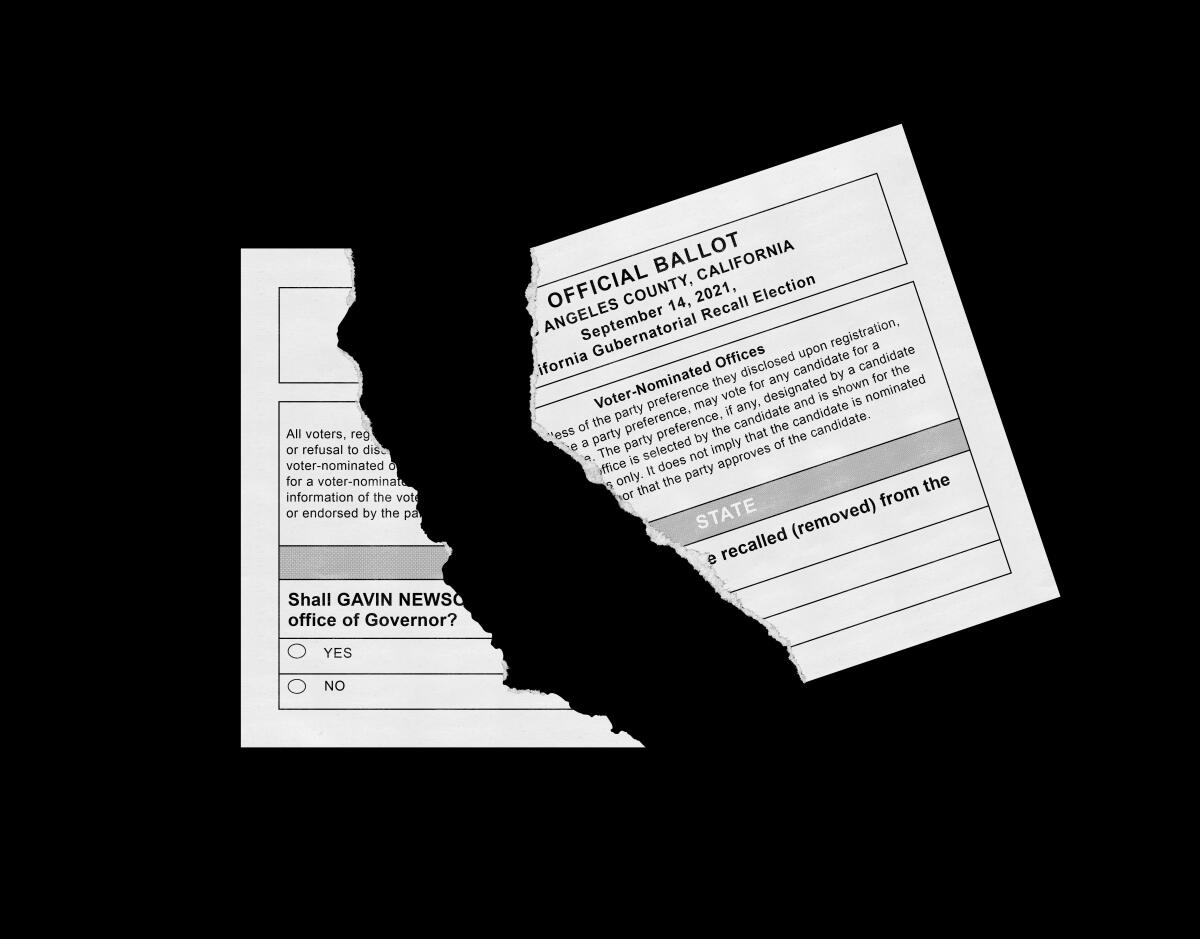

The election is Sept. 14, though voting is already underway, with every registered California voter having been mailed a ballot. More than 5.7 million have already been returned.

In the public interest, we’ll refrain from the usual snark and poor attitude to offer an unvarnished account of how this recall election came to pass and what it could mean for the state going forward.

Some of Newsom’s difficulties are largely of his own making. He imposed a moratorium on capital punishment — a matter of principle, he said, that reversed a campaign pledge to abide by the pro-death-penalty sentiment expressed by voters. He’s been slow to address problems with California’s Employment Development Department, the agency that cuts state unemployment checks, which paid out billions in fraudulent claims.

His infamous dinner at the luxe French Laundry — sans mask, while urging others to stay home and keep safe — may prove to be the worst meal of his life.

But there are other factors, well beyond Newsom’s control, that are driving the recall effort. Not least are the raging COVID-19 resurgence that threatens once more to overwhelm the state’s hospitals, doctors and nurses, and a series of horrific wildfires ravaging some of California’s most precious places. A summer of discontents threatens to turn into an autumn of despair.

But the main reason voters are being summoned to the polls less than nine months before the next scheduled election is the relative ease of forcing a recall attempt in California.

Of the 19 states that allow such a vote, California has by far the lowest threshold, requiring signatures that reflect just 12% of the ballots cast in the last gubernatorial election. That means proponents needed to collect just under 1.5 million signatures in a state with more than 22 million registered voters to force a referendum on Newsom’s fate.

The cost of the election is about $300 million.

The ballot comes in two parts. The first asks voters whether they wish to recall Newsom before his term expires in January 2023. The second asks voters whom they would like as a replacement should Newsom be kicked out. There are 46 names listed, compared with 135 candidates in the 2003 recall; none possess the celebrity candlepower of Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger, who succeeded Davis.

This time the front-runner on the second half of the ballot is Larry Elder, a Los Angeles-based Republican talk radio host. Other contenders include fellow Republicans Kevin Faulconer, San Diego’s former two-term mayor; John Cox, a businessman who lost to Newsom in 2016; Assemblyman Kevin Kiley of Rocklin, and former Olympic athlete and reality TV personality Caitlyn Jenner.

The attempted recall of Gov. Gavin Newsom will go before voters on Sept. 14. Here are the details.

The rules don’t allow Newsom’s name to appear on this part of the ballot. The best-known Democrat running is Kevin Paffrath, who dispenses financial advice to followers on YouTube.

The rules also don’t require the top contender to win a majority of the vote to become governor. If Newsom falls short — even if 49.9% of the electorate wants to keep him in office — he will be replaced by whichever candidate receives a plurality of votes, however few that may be. He or she would then serve the remainder of Newsom’s term.

The governor is favored to prevail in just under two weeks and beat the recall, owing in good part to Democrats’ overwhelming registration advantage over Republicans. Newsom and his allies have sought to portray the campaign as an effort by the GOP to capture an office the party and its candidates couldn’t win under normal circumstances.

No Republican has been elected to statewide office since 2006, and the GOP faces another uphill fight in 2022 trying to break that losing streak.

Newsom’s ouster would be, to use that most California of metaphors, a political earthquake. It would reverberate nationwide and put a scare in Democrats coast to coast. It would also cement California’s status as a place not just more populous, more inventive and more diverse than any state in the country, but also more politically confounding.

More to Read

Get the latest from Mark Z. Barabak

Focusing on politics out West, from the Golden Gate to the U.S. Capitol.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.