Larry Elder’s views cost him listeners and even his best friend. But he won’t waver

For nearly four decades they had been like brothers: two young attorneys who bonded over shared cases and touch football games, growing closer with the blossoming of their families and careers — one becoming a law professor in Ohio and the other a Los Angeles talk radio host.

Wilson Huhn was Larry Elder’s best man, Elder the godfather to one of Huhn’s children. “I cannot thank my best friend, Will Huhn, enough for his love, support, and encouragement,” Elder, now a leading candidate for California governor, wrote in his 2012 memoir.

Then came Donald Trump. Huhn, the father of a disabled son, felt deeply offended when the Republican presidential candidate appeared to openly mock the physical disability of a New York Times reporter.

Though they had different political views, Huhn expected that Elder would share his feeling that Trump had displayed “absolute contempt” for people like his child, a young man the radio host had known and loved throughout his challenging life.

But during an acrimonious 2016 conversation, Elder refused to admit Trump had been wrong. “Larry could not tell the truth,” Huhn said in his first interview about the rift. The dispute devolved over email and ultimately ended their 37-year friendship. “When Larry was sending all-caps messages to me it became pretty clear that that was it.”

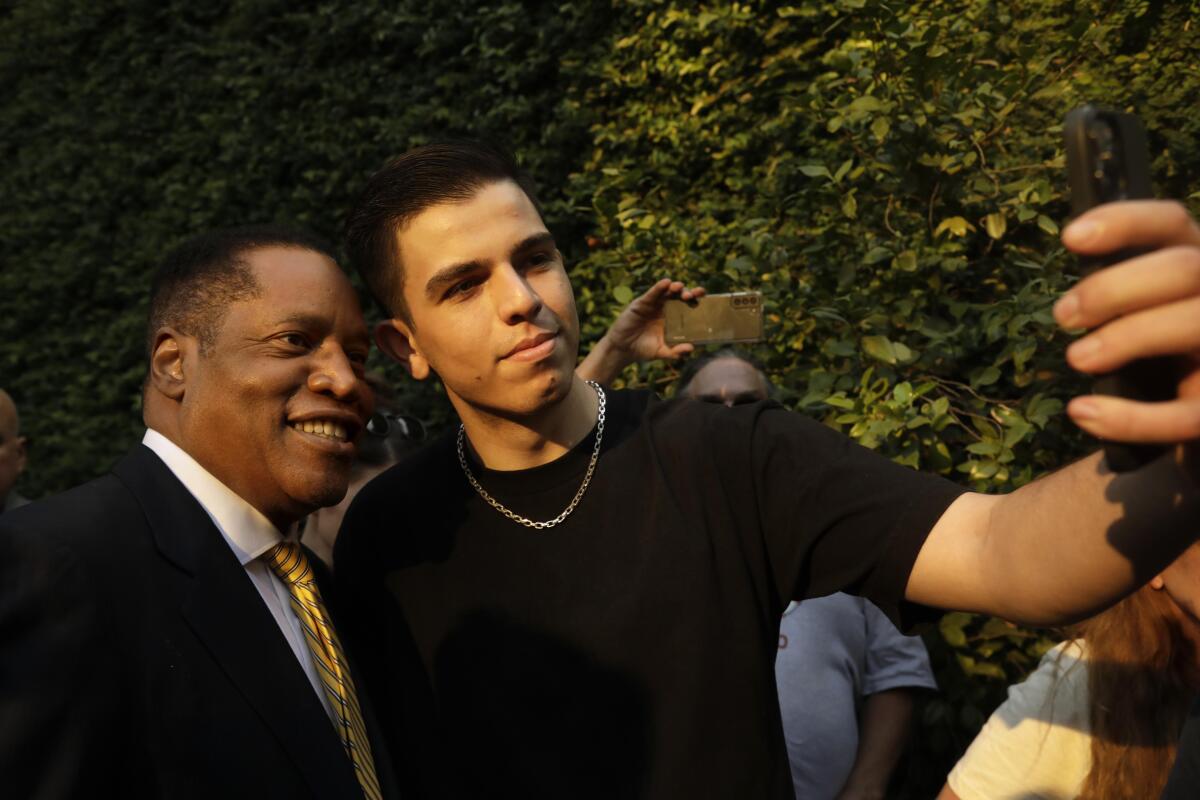

Though he has been in the public eye in California for nearly three decades, Laurence Allen Elder has never experienced anything like the tsunami of attention he has received in recent weeks.

The Times read books and columns by Elder, reviewed past radio commentaries and interviewed more than two dozen of his friends, professional associates and media peers — past and present — to learn more about the man currently best positioned to replace Gov. Gavin Newsom, should he be recalled in the Sept. 14 election.

What emerged was the portrait of a conservative raised in liberal South Los Angeles, a precocious young attorney, adept at arguing and winning, and a media provocateur, deeply committed to the libertarian values of small government and self-determination. Through it all, Elder has been perceived as a true believer who will not quit or back down.

Elder remembers the end of his closest friendship much differently. He would tell Huhn the same thing today that he did five years ago: “Donald Trump was not mocking a handicapped reporter. You were wrong.” After the argument, he sent his friend a three-page letter, detailing why the media also falsely reported that Trump had made sport of the reporter’s disability.

It appeared clear to Elder that the presidential candidate was reproaching the journalist out for waffling on an important story. He believes Huhn was blinded by his hatred of Trump, saying, “I thought that the basis on which he ended the friendship was unfair.”

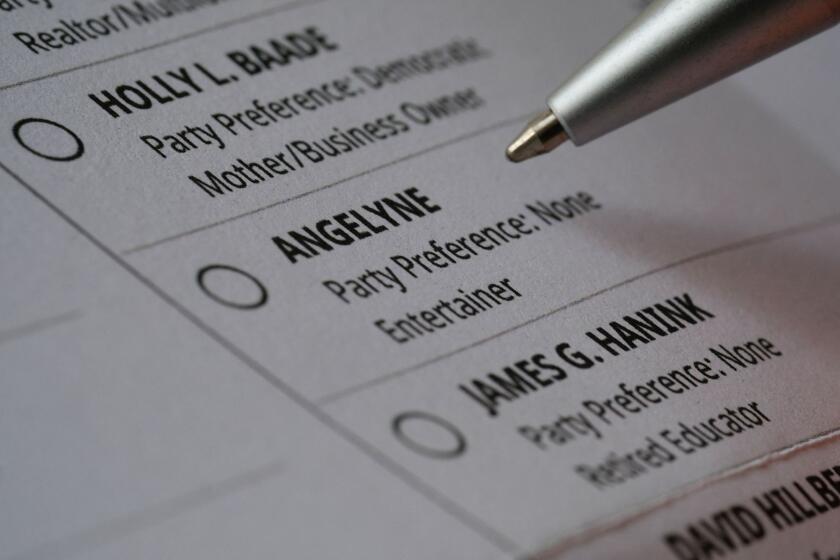

A primer on how voting by mail works, what the deadlines are, and how to track your ballot from the time it’s mailed to you to the time your vote is counted.

To friends and his new legion of supporters across California, Elder is unafraid to buck conventional wisdom, standing up to a battalion of feckless politicians, politically correct liberals and entrenched special interests, especially the left-wing media.

To Newsom, many Democrats and even some onetime Elder confidants, he is an extreme ideologue, who has little concern for the less fortunate and no idea how to manage an enormous state government, with a nearly $263-billion budget, 213,000 full-time employees and a public healthcare system that serves 12 million people.

‘They can’t pay me enough’

Like a lot of political talkers in the media, Elder had been urged many times before to run for mayor, governor or even president. But the 69-year-old Republican mostly mused about the reasons why he wouldn’t run.

“They can’t pay me enough. I can’t take the pay cut to go into politics,” Elder replied when fans would ask him to run for office, according to a former radio executive who asked to remain anonymous to preserve professional relationships. Elder once told an audience in Oakland that he felt his ideas, such as taking the government out of healthcare, “were way too radical for people to accept.”

But Elder said he later came to believe that more Californians were coming around to his views. Then some of his allies — including his barber, conservative talk radio host Dennis Prager and Christian evangelical pastor Jack Hibbs — encouraged him to run for Newsom’s seat. (Hibbs has questioned whether COVID-19 could be the “mark of the beast,” or anti-Christ. Elder has said he believes in the vaccine but does not want government to coerce Californians into inoculations.)

Though he had once judged California “ungovernable,” given super-majorities the Democrats hold in the Legislature, Elder said he did some research that changed his mind. He now says that he could make a mark, through vetoes, the “bully pulpit” of public persuasion and by declaring emergencies that would allow him to, for example, build more housing and fire incompetent teachers.

He entered the race on July 12.

‘I hated my father’

Growing up in Los Angeles, Elder would sit with his mother and pore over a picture book of American presidents, from George Washington to Dwight D. Eisenhower, he would later recall. “Larry, some day, if you want, and if you work hard, you can be in there,” Viola Elder said of the book.

He added: “It never occurred to me that she was wrong.”

Elder’s belief in himself grew out of his parents’ insistence that obstacles, including racism, could be overcome with hard work and determination. In another learning moment, during his time at Crenshaw High School, the younger Elder shared a poem, in which a Black man bemoaned how a summerlong trip to Baltimore was ruined after he was called the N-word. His mother listened to the poem and responded: “It’s too bad he let something like that spoil his vacation.”

Despite his expressions of love for both his parents, Elder did not grow up in a happy home.

His parents quarreled and never showed a hint of affection for each other, according to his memoir, ”Dear Father, Dear Son.” His father beat Larry and his two brothers, using a telephone cord and a belt, punishing the boys for relatively minor infractions like sassing their mother or splashing water during a bath.

“The louder we hollered, the harder he swung. Our welts were visible for days,” he wrote in the 2012 book. “I hated my father — really, really hated him. ... He seemed to resent us for being alive, for having to be fed, housed and clothed.”

Father and son reconciled after Elder completed law school at the University of Michigan and was working in Cleveland. As described in his book, he confronted his dad in the diner he owned just west of downtown L.A. — purchased by scraping together money from two janitorial jobs.

The son objected to how he and his brothers had been treated. His father told him about his own abusive childhood in Alabama and how he had survived through hard work and self-discipline, the book says. That message became a leitmotif throughout Elder’s media career.

At Crenshaw, he said he was the studious sort, picked on by other kids. But he had a defender in Perry Brown, a top athlete. Brown would later tell The Times he felt Elder had “misused” his radio platform so badly that Brown sometimes couldn’t stand to listen.

Elder left L.A. for Brown University in Rhode Island, a move he acknowledged had been facilitated by affirmative action. He later argued that race-based preferences have done more harm than good.

As a top student, Elder said he would have gotten into a good college even without affirmative action. He rejects racial preferences as hurting more qualified students, particularly Asian Americans, while also backfiring on those who got special preferences.

“The people that supposedly benefit end up dropping out,” he said. “You put somebody in a campus where the pace is too fast, and they’re not going to be able to keep up.”

Trading Ohio law for L.A. talk radio

“Larry’s extremely quick-witted. And he can talk rings around anybody.” That’s the conclusion his old friend, Huhn, reached when the two worked as associates at Squire, Sanders & Dempsey, a prestigious national law firm, based in Cleveland. (Following mergers, the firm is now known as Squire Patton Boggs.)

Elder won nine of the 10 cases in which he represented employers in workers’ compensation disputes, Huhn recalled. “He was probably the best litigator at that firm as a young man right out of law school,” said Huhn, who became a law professor at University of Akron and Duquesne University.

A bit of serendipity got Elder his first radio hosting gig. Elder had been invited on a Cleveland station as a guest. He proved so agile on the air that, when the regular host went on vacation the following week, the program director asked Elder to fill in.

Elder’s wife at the time, a doctor, asked him what he thought about the offer.

“I think of talk radio as stupid, shallow and glib,” Elder said.

“It is. You’d be good at it,” his wife, Cynthia, said.

Elder: “Which gives you an idea of that marriage.”

The couple split after less than two years. But Elder had established a toehold in radio and TV, one that grew substantially when a guest host from Los Angeles, Prager, visited Cleveland in the early 1990s. The attorney, who had a weekly spot on the program, quickly impressed Prager.

“I knew immediately I had met an exceptional man,” Prager said via email, adding that Elder stood out for “his quick mind, his voluminous knowledge, his life-loving personality, and his courage.”

Prager persuaded his home station, KABC in Los Angeles, to give Elder a shot.

Elder returned to his hometown in 1994, two years after the civil unrest following the acquittal of the officers who beat Rodney King, and in the midst of the O.J. Simpson murder case. The program director at rival KFI, David G. Hall, felt KABC made a “creative move,” bringing on “this guy from South-Central who swung the other way on race.”

Almost from the beginning, the self-proclaimed “Sage from South Central” whipped up a furor. He mixed sound bites from Rep Maxine Waters with a recording of a barking dog. He said “Blacks exaggerate the significance of racism,” while women did the same in regard to sexism. His website listed “Fifteen Ways to Avoid Being Called an Uncle Tom.” Sample: Always refer to the L.A. riots as an “uprising.”

Some Black people and their allies soon launched a boycott of advertisers attached to his show. By 1997, KABC estimated it had lost $5 million in ad revenue, Elder later said. The station cut Elder’s show in half.

Elder and the “Elderados,” his most loyal fans, fought back. His supporters launched a TV ad campaign calling the host as a victim of racism. Even the local American Civil Liberties Union spoke out against boycott “censorship.” Within three months, Elder had his old slot of 3 p.m. to 7 p.m. restored.

Mentoring Stephen Miller

Elder embodied the life of the “other,” the conservative guy from the liberal side of town. He found a kindred spirit one day in the late 1990s when a student from Santa Monica High School called his show to commiserate.

Stephen Miller was a conservative, stuck in the “People’s Republic of Santa Monica” and fuming about what he saw as his school’s leftist culture. He demanded students and staff regularly recite the Pledge of Allegiance. He criticized condom giveaways and called Spanish-language announcements “a crutch ... preventing Spanish speakers from standing on their own.”

The teenager spoke Elder’s political language. And the host responded by having Miller on the air almost anytime he wanted a platform. Over several years, including when he attended Duke University, Miller said he appeared 69 times on Elder’s show.

“I hope to live to see the day when you become president,” Elder emailed Miller in 2016, the communication shared with author Jean Guerrero, now a Times opinion columnist. “Your kind words are heartening beyond measure,” Miller responded, calling Elder “the one true guide I’ve always had.”

Miller’s appearances on KABC made him a recognizable figure in the larger conservative universe, helping to connect him with Steve Bannon, David Horowitz and others tied to Donald Trump. By extension, the Elder connection became Miller’s ticket to the White House.

The Santa Monica firebrand would go on to be one of the architects of Trump’s ban on travel from several predominantly Muslim countries, as well as the policy that separated children from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border.

When asked in an interview about his relationship with Miller, Elder shifted to the confrontational style that’s been his radio hallmark.

“I just find it fascinating, why you’re focusing on Stephen Miller,” he said. “Can you explain to me why this is important?”

He then asked why The Times didn’t ask about other regular guests on his show, including conservative commentator Michelle Malkin, former Los Angeles City Councilman and Police Chief Bernard Parks and Gloria Allred, the feminist attorney and liberal political activist.

Elder then said he had not had significant contact with Miller since he joined the Trump White House, as both men were busy with their careers.

“Do I feel that what Stephen Miller did was wrong in stopping illegal immigration?” Elder asked. “No, I don’t. I don’t believe in illegal immigration. I think our borders should be secured.”

Seeking the national spotlight

Co-workers from his early days at KABC recall that Elder aspired to a national stage, preferably on both radio and television. He told friends he was as good as or better than Bill O’Reilly and Sean Hannity, two giants of conservative commentary.

“He wanted to be a media icon,” said the former executive. The trouble was that Elder struggled to prevail during his time slot in Southern California. He suffered the ups and downs of many hosts in radio, with new challengers in podcasts and satellite radio.

His show became syndicated in the early 2000s, but the deal ended after five years. Superiors at KABC dogged him for being too focused on racial issues, even when the audience, and the world, turned to other topics, such as terrorism.

He bridled when management tried to tell him what to talk about, two former co-workers said. (One considered Elder’s subject matter plenty diverse. The other called him “a one-trick pony.”)

He lost his job at KABC in 2008, came back two years later, then got bounced out again in 2014. Management said it needed to raise ratings. Elder insisted his bosses retaliated against him for slamming Bill and Hillary Clinton for the sexual abuse allegations against the president.

Like many others in the industry at the time, the station manager (who did not return requests for comment) reportedly worried that the audience for conservative call-in shows was aging and, literally, dying off. So KABC brought in frothier hosts, such as Dr. Drew Pinsky and lifestyle commentator Jillian Barberie.

Sensing his slot at KABC was in danger, Elder began setting up a studio in his Hollywood Hills home. Fired by KABC on Dec. 2, 2014, he turned up the next day, hosting the first streaming version of his show on Elderstatement.com.

“He’s unstoppable,” said Patricia Stewart, who was Elder’s girlfriend for 16 years and co-worker at KABC. “He’s like that inflatable toy when you are a kid, you punch it down and it pops right back up again.”

Accusations after a breakup

The latest incarnation in Elder’s media odyssey came in 2015.

He was in the midst of a breakup with his live-in girlfriend, Alexandra Datig. She had helped arrange for him to get his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and Elder thought it would be great to cap that ceremony with the couple marrying, right on the spot, she recalled.

But Datig, 51, broke off the relationship and has turned into one of Elder’s most persistent critics.

Datig filed a report with Los Angeles detectives, accusing Elder of once pushing her and engaging in the other actions that she said amounted to emotional abuse. Prosecutors said Friday that they would not examine the case because the statute of limitations had passed.

“I am going to deny brandishing a firearm, loaded or unloaded, at anybody, anytime,” Elder said. “I am going to deny the allegations of domestic violence.” He has said repeatedly he believes the allegations are a distraction from the important issues facing California.

People close to Elder, including Stewart, have risen to his defense.

The 61-year-old said that in her long relationship with Elder she had “nothing but good experiences,” adding: “This is a man who loves women and respects women.”

The year 2015 also brought another career resurrection. In August, “The Larry Elder Show” became syndicated via the Salem Radio Network.

“Out of the ashes, a phoenix rose,” said his agent, Michael Horn. “And in this case it was something Larry always wanted: To be a national talk show host.”

And Elder’s voice gets magnified, via newspaper columns and frequent appearances on Fox News. An online search shows he has been a guest on the conservative cable outlet 220 times in the past five years. The radio trade publication Talkers named Elder No. 18 on its “Heavy 100” list of the most influential figures in the business.

“I think he’s as honest as they come,” said Stephen Sacks, who became an Elder fan, and then close friend, when he wrote to KABC more than a quarter century ago. “He forms his opinions based on data. And he’ll change his mind if you can convince him that he’s wrong about something.”

If there has been an irritant in his 2-month-old career as a politician, it has been the media. Coverage by the Los Angeles Times and its opinion columnists has particularly infuriated him. As has the newspaper’s failure to write about, or review, his books, including the 2012 memoir. “It is completely unfair,” he said in an interview Friday.

He said the break with Huhn also troubles him. He noted that he has “no relationship” with two or three other friends because of their loathing of Trump. He couldn’t fathom why the “left wing” Huhn expected him to break with Trump. “I’m a Republican, for crying out loud,” he said, adding later, “I’m more than willing to revive a friendship, if he is.”

Huhn said he found it difficult to speak out about a man who he still cares about.

“I still love him (as a friend),” Huhn said in an email. “But it is terribly important that he not have any control over other people.”

Win or lose, Elder said he will remain that strong and persistent voice.

“I don’t know quite what my journey is going to be,” he said. “But my life now has changed forever.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.