Will Taliban surge in Afghanistan hurt Biden politically? Or are Americans done with the war?

WASHINGTON — As Afghanistan’s provincial capitals fell in astonishingly rapid order to the Taliban this week, President Biden made it clear he has no regrets for withdrawing American forces from the country after two decades. A politician known for his deep reserve of empathy, Biden has offered surprisingly little solace to the Afghan people: “They’ve got to fight for themselves,” he said Tuesday.

There is no doubt that Biden’s decision is rooted in deep personal conviction — and a calculation that Americans no longer see a rationale for continuing “the forever war” to stabilize Afghanistan’s fledgling democracy. Nevertheless, ending the two-decade U.S. campaign has allowed the Taliban to reassert its power with an onslaught far more swift than what Biden predicted just last month — a devastating denouement that could put the president in political peril.

“This is not going to end well,” said Chuck Hagel, a former Republican senator and a Defense secretary under President Obama. He praised Biden’s “courage” for making a firm decision, calling it “the right thing to do,” but predicted there would be political consequences.

“Very likely Kabul will fall and he will be seen, moving right into the next election, as the president who wasted 20 years, pulled Americans out and lost Afghanistan,” Hagel said.

Biden has long argued for bringing the conflict to an end, an exit that eluded his predecessors. When he took office, the U.S. military presence had been scaled back to around 3,500 troops.

Biden announced in April that he would withdraw the remaining U.S. forces by Sept. 11 — the anniversary of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, which Al Qaeda planned from Afghanistan. To generals’ earlier warnings that a rapid withdrawal would allow the Taliban to gain ground, Biden said the time had come to reorient America’s defense priorities toward more urgent threats.

“We went to Afghanistan because of a horrific attack that happened 20 years ago,” he said at the time. “That cannot explain why we should remain there in 2021.”

While numerous Republicans in Congress are already criticizing Biden over the withdrawal, it remains unclear how much of the American public is concerned about the fate of Afghanistan or even paying attention to news of the Taliban’s steady overtaking of the government the U.S. has spent more than $2 trillion shoring up over the last two decades.

Seven in 10 Americans back Biden’s decision to withdraw, according to a July poll by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, including 77% of Democrats and 56% of Republicans.

“An overwhelming majority of Americans think this is the right idea, and that’s what politics is all about,” said Ivo Daalder, Obama’s former ambassador to NATO. “If the answer is $2 trillion, 20 years only to see it fall in two weeks, I don’t see the American people saying that’s a good deal, let’s do it all over again.”

Recent polling has also revealed new public skepticism about the origins of the war launched by President George W. Bush. Now a growing number of Democrats and independents have come to view the war itself, long seen as defensible in comparison with the conflict in Iraq, as a mistake.

“That’s a big reason why I would not expect this decision [to withdraw], even with the visuals of the Taliban taking over, to have a big effect on Biden’s approval rating,” said Frank Newport, a senior pollster at Gallup.

As the Taliban seize more of Afghanistan, the Biden administration is sending troops to the Kabul airport to help move U.S. Embassy staff and other Americans.

Recent surveys also show that people in the U.S. are primarily concerned about the deadly COVID-19 pandemic and the economy. Roughly half the country, polls have shown, doesn’t follow any news about Afghanistan.

But until now, Afghanistan was rarely in the news. In recent weeks, coverage of a deteriorating situation has ramped up as the departure of U.S. forces has allowed the Taliban to capture vast terrain. On Thursday, the Pentagon announced it was sending some 3,000 troops — about the same number as the U.S. was withdrawing — to help remove U.S. Embassy personnel from Kabul.

That’s drawn comparisons to the helicopter rescue of Americans from the embassy in Saigon, undermining Biden’s assertion last month that the situation in Afghanistan was “not at all comparable” to the U.S. exit from Vietnam in 1975. “There’s going to be no circumstance where you see people being lifted off the roof of [an] embassy,” he said. “The likelihood there’s going to be the Taliban overrunning everything and owning the whole country is highly unlikely.”

Many Afghans fear imprisonment or execution by the Taliban, an Islamist group that ruled brutally in the 1990s; women in particular have said they fear a return to repression, and tens of thousands who aided U.S. forces as interpreters or contractors are especially vulnerable to violent retribution. Human rights groups say they are already getting reports of Taliban atrocities.

Rep. Michael McCaul (R-Texas), the ranking GOP member on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, said Biden and the State Department were painting a “rosier picture” of the reality than the intelligence community was relating. “President Biden’s lack of leadership has enabled the deteriorating situation on the ground in Afghanistan,” McCaul said. “He will be abandoning our Afghan partners and the women of Afghanistan to be slaughtered — and he will own the horrific images that come from it.”

As the U.S. hastens to exit Afghanistan by Aug. 31, women fear a potential return to power by the Taliban and its harsh view of their role in society.

Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) has requested a full House briefing on Afghanistan when the House returns to session Aug. 23. The politics of Afghanistan don’t align with the usual partisan divide, splitting Democrats and Republicans. Both parties, of course, have had presidents who continued the war.

For months, Biden’s advisors insisted they were bound by the February 2020 agreement that the Trump administration signed with the Taliban in Doha, Qatar. Under President Trump, the U.S. agreed to begin withdrawing its troops by May of this year if the Taliban agreed not to attack them.

Although many other elements of that pact were routinely violated by the Taliban, Biden insisted on sticking by the one point that he instinctually and politically favored: bringing Americans home.

But critics said the agreement was fatally flawed from the beginning because it excluded the Afghan government. That in turn demoralized Kabul and its armed forces, and gave long-desired legitimacy to the Taliban. It began a long disintegration of the Afghan government’s ability and willingness to fight and emboldened the Taliban, analysts said.

Biden’s contention that a deal made with a group like the Taliban by a previous administration had to be respected was “worse than disingenuous,” said Ryan Crocker, former U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan, Iraq and other countries.

“From the day we sat down with the Taliban, this deal wasn’t about peace. It was about surrender, American surrender, and the complete delegitimization of the Afghan government and army,” Crocker said.

Yet Biden also risked a new round of American casualties — something avoided in more than a year in Afghanistan — if he had backed out of Trump’s bargain. More than 2,400 U.S. troops and over 3,800 security contractors were killed in the war and more than 20,000 service members injured. Afghans have paid a far higher toll.

Biden “was dealt a terrible hand, and he made it worse,” Crocker said.

Now the message “will ping around the world” that the “righteous arms of the faithful” — as Taliban militants cast themselves — have driven American forces from Afghanistan, he said.

As U.S. forces pull out from Afghanistan, the Taliban is in the ascendant — and threatening to retake the city that was its former spiritual capital.

Former Michigan Rep. Justin Amash, an ex-Republican who is now a Libertarian, tweeted Friday that Taliban gains “underscore the futility of permanent occupation. The United States wasn’t able to meaningfully shape circumstances through 20 years of war. We’d have seen the same results had we pulled out 15 years ago or 15 years from now.”

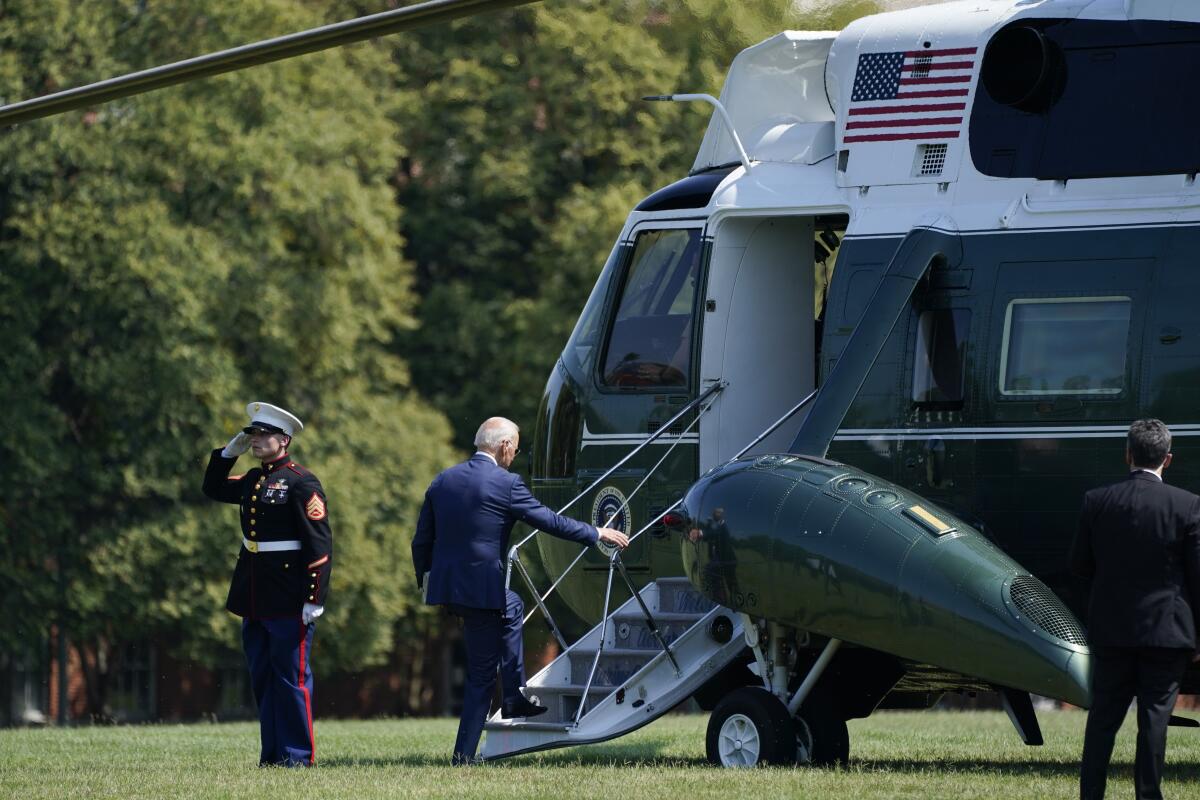

Ron Klain, Biden’s chief of staff, retweeted Amash’s statement, one of the administration’s few public acknowledgments of Afghanistan on Friday. The White House later Friday tweeted a photo of Biden at Camp David being briefed on Afghanistan by phone.

The increasingly harrowing reality of Afghanistan will play out just as Democrats are straining in the weeks ahead to advance Biden’s domestic agenda, a $1-trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill and a $3.5-trillion budget that would amount to a dramatic expansion of the social safety net. Beyond Washington, an ugly withdrawal from Afghanistan could undermine Biden’s attempt to convince U.S. allies that “America is back” as a global leader.

One former U.S. diplomat in the region, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that Biden often recalls to people how he recognized on his numerous visits to Afghanistan as vice president that top military officials had overstated the strength of the country’s democratic regime.

“He knew the military was overpromising and underdelivering,” the former diplomat said. “He saw through the military always asking for ‘a little more time’ — and it’s clear as these provincial capitals fall like dominoes, that another five years wouldn’t have solved the problem.”

But, the diplomat continued: “Even if you’re right, that doesn’t change the ugliness of it all. And even if it’s not a big political loss, around the world people will look at it as a sign of: ‘Don’t rely on America.’”

With peace talks in Doha not expected to produce meaningful results, several former officials and experts said the only solution may be a massive United Nations-led humanitarian intervention that would include peacekeepers and guarded enclaves where Afghans could shelter from the Taliban. But any such mission would have to be led by an international coalition, not the U.S., they said.

The United States “can be involved but not leading it,” said Earl Anthony Wayne, a former career U.S. diplomat who was stationed in Afghanistan. “We’re tainted goods.”

But many are willing to live with whatever complications arise from Biden doing what his predecessors over 20 years have not.

Gil Barndollar, who was deployed twice in Afghanistan and is now a senior fellow at Defense Priorities, a group that supports withdrawal, said that there was plenty of blame to go around in explaining the swift advance of the Taliban but that withdrawal was long overdue.

“You can quibble with pieces” of how the U.S. withdrawal has occurred, he said, but “a healthy majority of Americans agree that the war is already lost, and at some point you have to rip the Band-Aid off.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.