With Biden’s first budget, annual federal spending would top $6 trillion

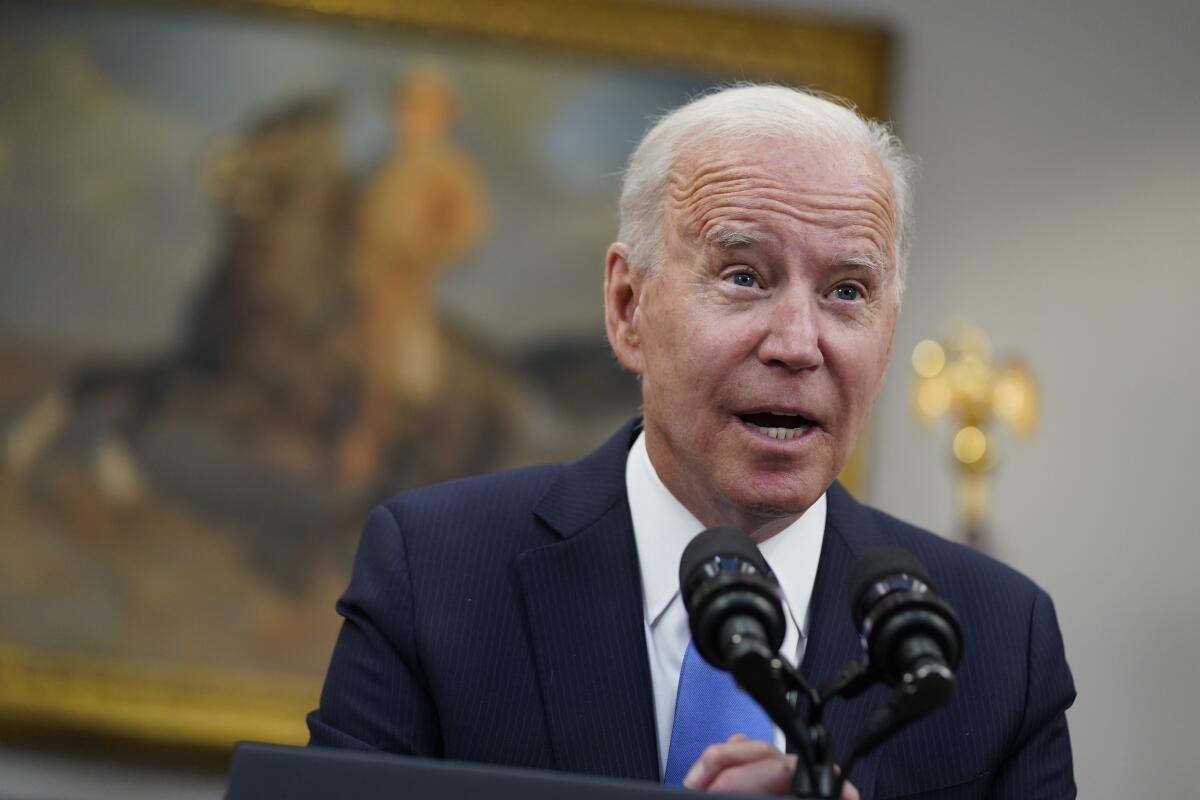

WASHINGTON — President Biden on Friday proposed a $6-trillion budget for the coming fiscal year, reflecting both ambitious goals for reinvigorating the economy through government action and a head-on challenge to his Republican opponents in Congress.

By seeking billions of additional dollars for new infrastructure, aid to education, help for middle-class families, new environmental programs and a host of other domestic initiatives for fiscal year 2022, which begins Oct. 1, Biden promises to ramp up economic growth and make the United States more competitive globally, boost the long-stagnant incomes of most American workers and combat climate change.

And by proposing the largest annual federal budget in constant dollars since World War II, including widely popular domestic programs, he is laying down a political gauntlet to Republicans who are betting they can obstruct his initiatives and break Democrats’ shaky majorities in Congress in next year’s midterm election.

Shalanda Young, Biden’s acting budget director, said the initiatives, if enacted, would be “transformational,” telling reporters Friday, “This budget will grow the economy, create jobs and do so responsibly by requiring the wealthiest Americans and big corporations to pay their fair share.”

Any president’s budget request to Congress is primarily a political document, a fiscal blueprint spelling out the administration’s priorities.

For example, the president’s budget includes a $14-billion increase to tackle the climate crisis; $10.7 billion more to combat the opioid epidemic; an additional $20 billion for schools in high-poverty areas; and an $8.7-billion increase for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to boost its ability to detect and respond to global health crises like the coronavirus pandemic.

Biden is not, however, requesting funding for expanding healthcare coverage beyond the tax credits and enhanced subsidies that were part of the temporary $1.9-trillion pandemic relief law he signed in March. Instead, he calls on Congress to pass legislation this year to expand in-home care, to lower the cost of prescription drugs, long a priority for Democrats, and to reduce the age of Medicare eligibility to 60.

Biden is the first president in more than two decades not to include the Hyde Amendment, which prohibits federal funding for abortions, in his budget. The move made good on a campaign promise, but with Democrats’ narrow majorities in Congress, actually eliminating the law is unlikely.

Under Biden’s budget proposal, the federal deficit for the next fiscal year would hit $1.8 trillion, considerably more than the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office projected in February based on current spending and taxes. That deficit would be less than the $2.3-trillion shortfall expected for the current fiscal year, however, or the $3.1-trillion deficit for fiscal 2020 — periods when the economic downturn amid the pandemic, along with the tax cuts President Trump signed into law in 2017, contributed to much-reduced government revenues.

Biden’s plan to increase taxes on corporations and the very wealthy would offset the cost of infrastructure and social programs over 15 years, the administration has projected.

“The president’s budget improves the long-term fiscal outlook because his policies are paid for over the long run,” Young said.

Republicans, however, are calling the higher taxes on corporations and the wealthiest Americans a “red line” in any negotiations. While they’re assailing Biden for proposing to raise taxes, most Americans would see tax cuts. Republicans also are criticizing Biden for his budget’s projection of yearly deficits exceeding $1 trillion, yet they said little when red ink hit that level under Trump.

“President Biden’s proposal would drown American families in debt, deficits and inflation,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said in a statement. Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, the ranking Republican on the Senate Budget Committee, called the proposal “dead on arrival.”

Of the $6 trillion in spending Biden is proposing for next year, more than half is for Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and other mandatory federal obligations that are set in law. Much of the rest maintains funding for existing military and domestic programs.

Yet Biden’s proposed additions are significant. The spending for infrastructure and social programs, together with tax breaks for all but the wealthiest Americans, would cost roughly $4.5 trillion spread out over 10 years.

Biden, speaking at Cleveland Community College on Thursday in advance of sending his budget request to Congress, said, “This is our moment to rebuild an economy from the bottom up and the middle out.”

He argued that investments in infrastructure, workers and families will make America’s economy fairer and help the country keep pace with global rivals, China in particular. And he continued to push for his proposals to raise taxes on corporations and the richest individuals to pay for the investments and tax breaks for low- and middle-income households, mocking Republicans for opposing those tax increase plans even as they attacked his spending proposals as budget-busters.

“We had no problem passing a $2-trillion tax plan that went to the top 1% that wasn’t paid for at all,” he said, referring to Republicans’ 2017 law that drastically lowered tax rates for corporations and the rich. “But every time I talk about tax cuts for working-class people, it’s, ‘Oh, my God, what are we going to do?’”

Congress invariably reshuffles White House spending plans, sometimes all but ignoring them. But with Democrats in control of the House and Senate, if narrowly, Biden can expect a respectful hearing for much of his first full-year budget proposal, and some success.

While polls show the popularity of many of Biden’s proposals, pressing his plans without bipartisan buy-in would be a political gamble given the highly polarized electorate.

The president and a relatively few Republican lawmakers continue to negotiate on an infrastructure bill. Yet most Republicans have balked at the far more active role Biden envisions for the government, while raising concerns about the risks of inflation and other economic dangers of increasing the nation’s already large debt.

In this decade, the U.S. would be facing an unprecedented level of debt. One common measure of fiscal sustainability is debt as a share of the nation’s gross domestic output, or economic output. That ratio was about 80% before the pandemic but hit 100% at the end of last year and would rise to 117% by 2031 under the Biden budget — 10 percentage points higher than what the CBO had projected in February in its baseline forecast.

Economists say that level of debt to GDP would still be manageable as long as the United States, the world’s largest economy, is continuing to grow, the dollar is the world’s reserve currency and interest rates remain very low.

“I would expect a lot of hype and fearmongering about the debt,” said Seth Hanlon, a senior fellow at the liberal Center for American Progress and a former special assistant to President Obama on tax and budget issues.

But he noted that, over the last decade, many analysts and economists have come to view past hand-wringing over the federal debt as overdone, and to agree that those concerns should not be a priority at a time of crisis and low interest rates.

“Getting bipartisanship is, all things equal, better than not,” Hanlon said. “But one lesson that was learned from the Obama years, and particularly the drawn-out passage of ACA [the Affordable Care Act] is that the longer you drag it out, the harder it gets.”

Marc Goldwein, senior policy director for the centrist Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, said Obama also sought policies like universal pre-K and community college education, as well as bigger tax increases, but his proposals were less ambitious and his budget “did tend to take more incremental approaches.”

“I think that the Biden budget is directionally similar to the Obama budget but much larger,” Goldwein said.

The Biden administration’s budget projections are based on its forecast of economic growth of 5.2% this year, 3.2% next year and less than 2% over the long term. Those are consistent with, if slightly more conservative than, forecasts made by the Federal Reserve and many private-sector economists.

Biden’s budget also assumes continued low inflation and interest rates. But some economists, including Obama-era Treasury Secretary Lawrence H. Summers, have warned about the risks of rising prices given massive federal spending and the pent-up demand and excess savings from the pandemic. And recent data suggest that the administration may be too sanguine on inflation.

The government said Friday that the Fed’s preferred measure of core inflation was up 3.1% in April over a year ago, well above the central bank’s target of 2% inflation. Biden’s budget assumes inflation at 2% this year and never exceeding 2.3% over the decade. Fed officials view the recent jump in inflation as “transitory,” reflecting an economy that is experiencing the ups and downs of getting back to normal after a devastating pandemic.

However, consumers apparently are getting worried. The University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index showed a sharp drop in confidence Friday “due to surging inflation that consumers anticipate will persist in the year ahead.” Higher inflation could, in turn, force the Fed to hit the brakes and push up interest rates, making it much more costly for the government’s borrowing; Biden’s budget assumes 10-year Treasury yields to stay below 3% through the decade, well below the historical rate.

“It sounds like a budget that could cause inflation to heat up despite their forecast not going appreciably above 2%,” said Chris Rupkey, chief economist at FWDBONDS, a financial market research firm.

“The optics of a $6-trillion number is not great, but the market seems to be looking the other way on this right now,” he added, “and I think part of the reason for that is we’ve already been given $6 trillion worth of plans from the Biden administration.

Economist Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics said that he expects that Biden will eventually come away with a $2.5-trillion package of new spending on infrastructure and social programs, plus tax credits, over 10 years — not $4.5 trillion. And instead of $3.5 trillion in higher taxes over the decade, Zandi expects about $1.5 trillion will end up as law by year’s end.

“This budget is aspirational. It’s laying out a blueprint for the administration’s objectives, goals and how to get there,” Zandi said. “So they don’t expect to land on Mars, but they are going to propose and go to the moon.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.