Democrats promised to lower drug prices, but plans are sputtering

WASHINGTON — With control of Congress and the White House, Democrats have an opportunity to bring down prescription drug prices, addressing one of voters’ top concerns and finally fulfilling a campaign pledge Speaker Nancy Pelosi made to voters 15 years ago.

Despite widespread support among Democrats, the idea has sputtered, however, as President Biden left it out of his infrastructure plan and is expected to leave it out of his budget while congressional Democrats remain noncommittal about how they might enact it. The initiative has fallen victim to extremely slim majorities and division among Democrats.

Since at least 2006, Democrats have promised to drive down prescription drug costs by requiring Medicare to negotiate with drugmakers to get the lowest prices possible for the medications it covers. Over time, the policy proposal was expanded to include the private insurance market, allowing many more Americans to benefit from the lower rates. There would also be a new $2,000 annual cap on drug costs in Medicare and drugmakers would have to explain significant price hikes.

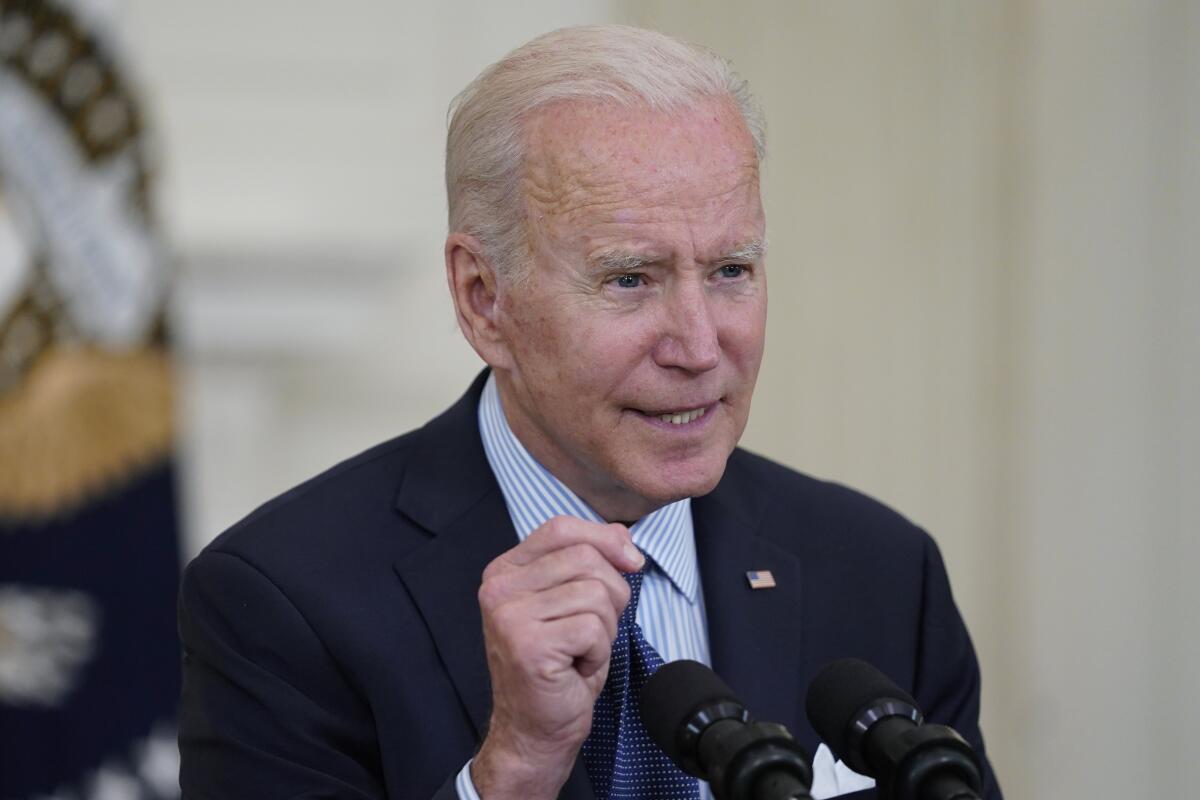

Biden addresses a joint session of Congress, pared down by pandemic precautions, in a prime-time appearance Wednesday to promote a bold domestic agenda.

Dozens of rank-and-file Democrats lobbied the White House to include the price negotiation — as well as a large expansion of Medicare eligibility — as part of the infrastructure plan. Biden rebuffed their request but gave the policy attention in his first address to a joint session of Congress, urging lawmakers to “get it done this year.”

The last two Democratic presidents started their ambitious runs at major health policy reform in their first weeks in office — to opposite outcomes. President Clinton’s plan fell apart, but President Obama’s became the Affordable Care Act.

But Biden’s administration has instead prioritized two other sweeping legislative proposals, a combined $4 trillion in infrastructure upgrades, tax credits and subsidies for workers and families, raising questions among some Democrats about the president’s commitment to pursuing a plan to drive down drug prices.

Prescription drug reform and Medicare expansion are not expected to be in the president’s upcoming budget proposal, slated to be issued this week. White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said health policy remains a big priority, even as her words made clear it’s not an immediate one.

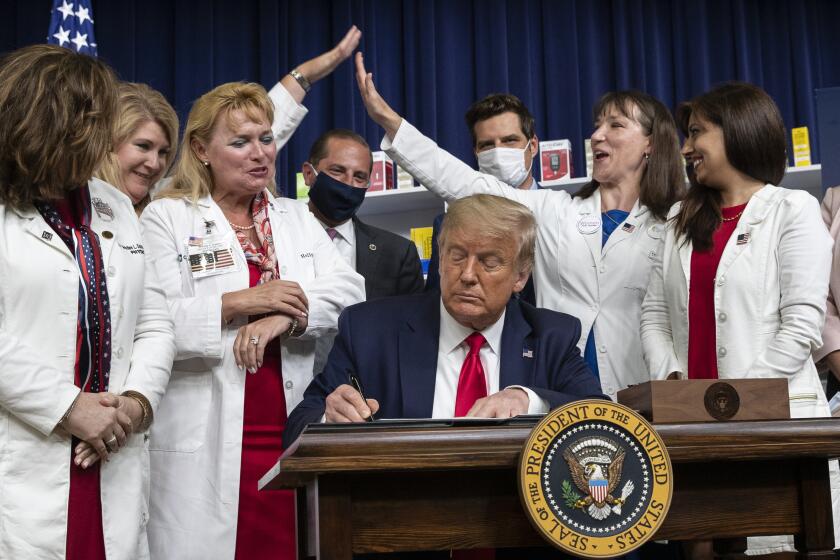

Trump’s drug price strategy was all talk and no action.

“Will every single thing he wants to get done in his presidency be reflected in his budget? It won’t,” she acknowledged. “But that doesn’t mean he’s not committed to it and it doesn’t mean he doesn’t have a desire to move all of these agenda items forward that he talked about in his joint session address and that he talked about when he was running for president.”

Outside groups and Democratic lawmakers are trying to build pressure on the White House to take action. Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), one of Congress’ top advocates of prescription drug reform, said the White House wants assurance that the policy can get through Congress.

“They want to know that it’s going to pass on the Hill, so we have certainly been doing a lot of advocacy with the White House,” Jayapal said.

Jayapal, Rep. Joe Neguse (D-Colo.) and Democrats from competitive political districts have met with Susan Rice, director of Biden’s Domestic Policy Council, to lobby on the policy, she said. Progressives Jayapal and Neguse joined with centrist Reps. Jared Golden (D-Maine) and Conor Lamb (D-Pa.) in a letter pushing Biden to expand access to Medicare and reform drug prices, an effort that now has 118 supporters.

Protect Our Care, an advocacy group that defends the Affordable Care Act, this month started a seven-figure messaging campaign to encourage Medicare price negotiation, including a television ad reminding voters of Biden’s campaign vision to reduce drug prices.

Inside the White House, aides have had numerous conversations with lawmakers about healthcare reform. In an administration teeming with veterans of the Obama White House, the early strategy has been guided in part by hindsight and a determination not to repeat past missteps, according to two officials, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

With healthcare, it’s not so much that Biden officials are looking to avoid a policy area that has been political quicksand for the last two Democratic presidents — and more of an effort to maintain a sharp focus on the president’s main priority, the officials said.

Even during Obama’s successful effort to enact the ACA, congressional Democrats spent months in a futile effort trying to win GOP support. “You have to keep the focus on the big things,” one of the officials said.

“This was a big part of the campaign and this president is very invested in his campaign vision,” said Chris Jennings, who worked on health policy in the Clinton and Obama White Houses and represented then-candidate Biden on the Biden-Sanders Unity Task Force. “This is one of the only cost containment policies that is overwhelmingly popular because it both reduces prices, premiums and cost sharing and also produces savings.”

Because of fervent GOP opposition to Medicare price negotiation, it would not be included in any deal Biden could negotiate with Republicans on infrastructure.

Democrats could attach the drug policy to an infrastructure plan to be approved in the Senate under reconciliation, the fast-track process that would circumvent a Republican filibuster. But that process is loaded with land mines: It would need the support of every Senate Democrat, and some parts of the policy could be stripped.

Sanders, a longtime supporter of the plan, said no bill would get past his Budget Committee without it.

House Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Frank Pallone Jr. (D-N.J.) was noncommittal about how the policy might get enacted.

One of the most attractive reasons for Democrats to enact the policy is that it saves the federal government about $500 billion. But even that upside comes with trouble: Democrats are divided about how to spend it. There is significant support for plowing the money back into Medicare in order to expand benefits; adding dental and vision coverage, and lowering the eligibility age. Others want to use the money to make permanent an expansion of ACA subsidies Democrats enacted on a temporary basis this year.

It is also has bipartisan support among voters, with a recent Kaiser Family Foundation poll showing that 79% of Americans feel prescription drug prices are unreasonable.

Democrats worry that after promising for years to tackle drug prices, there would be political consequences if they don’t make good on their pledge.

“Our future depends on what we deliver in the next year and a half, absolutely,” said Rep. Peter Welch (D-Vt.). “We would pay a political price if we don’t help Americans. And we’re pretty stupid if we don’t, because this is so popular politically.”

Pelosi, of San Francisco, has reminded reporters that it is the last unchecked box from the Democrats’ “Six for ’06” campaign promises from the 2006 election.

“There is no way in her last Congress as speaker, she’s not going to make a hard run for prescription drugs,” said a Democrat working on the policy, referring to Pelosi’s prior statements that this would be her last term as speaker.

But it’s a risky move: It would be difficult to find 50 Senate votes.

House Democrats were able to approve a prescription drug bill last year, but their tighter vote margins after the 2020 election could make it a more difficult climb this year. A group of 10 moderate House Democrats, led by Rep. Scott Peters (D-San Diego), issued a letter indicating they want a more modest alternative.

Peters said he voted for the bill in the last Congress as a means of getting the legislation moving, though he opposed the idea of allowing Medicare to use the price of drugs in other countries as a negotiating tool to set prices in the United States. He said he is seeking out alternatives that could get bipartisan support.

Similarly, pharmaceutical companies and many Republicans argue the policy will stifle innovation and threaten future development, like the lightning-fast creation of COVID-19 vaccines.

“This is a partisan bill that threatens the future development of new treatments and patient access to life-saving medicines, while doing little to fix the broader affordability challenges patients are facing,” said Brian Newell, a spokesman for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, an industry trade group.

The pharmaceutical industry is a legendary Washington lobbying force. In the first quarter of 2021 alone, it spent a record $92 million lobbying lawmakers on this and other issues, according to OpenSecrets.

But there are signs that the industry’s might is waning. In recent years, Capitol Hill has more frequently made small policy changes that hit drugmakers as a means to pay for other programs, such as year-end spending deals. And the Biden White House showed some teeth this month by supporting a waiver for COVID-19 vaccine intellectual property rights, a proposal drugmakers strongly opposed.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.