When Rep. Ro Khanna started pressing Vice President Kamala Harris to use her procedural power to push a national minimum wage hike a few weeks ago, he found himself targeted by a swarm of online Harris supporters.

“I see progressives are on message with the Blame the Black woman boogeywoman strategy,” an account called @blackwomenviews tweeted at Khanna, the Fremont Democrat.

“Your misogyny is showing,” wrote another, who added a GIF of a woman disdainfully tilting her head.

Khanna had aroused the wrath of the KHive, Harris’ extensive, loose-knit and fiercely loyal fan base, which celebrates and defends the vice president with equal fervor. Members of KHive, a riff on Beyoncé’s loyal fan base known as the Beyhive, sometimes use the hashtag #KHive in their social media posts, and many mark their allegiance in their Twitter profiles with yellow hearts and bee emojis.

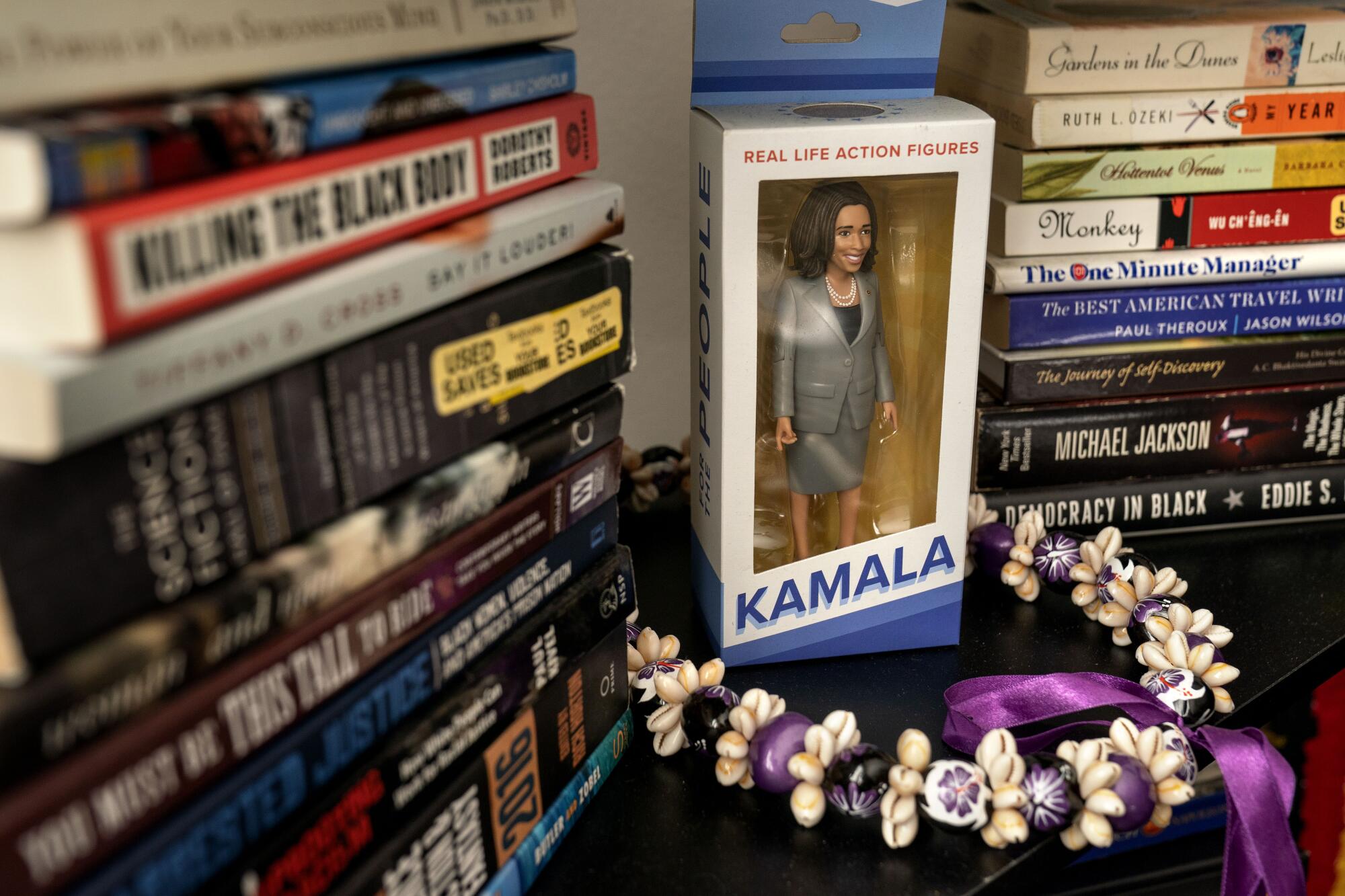

They share videos of Harris stepping off Air Force Two, make offline friendships, and wear socks and hoodies bearing her name and likeness. They organize virtual “cooking Sunday” parties and offer support to other hive members.

But it’s not all sweetness. Almost any politician, activist or reporter who has questioned Harris has felt the group’s sting.

“They’re vicious,” said Briahna Joy Gray, press secretary for Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) during the 2020 presidential primary, who tangled with the group more than once.

“I am not interested in talking about that subject at all,” said David Sirota, another former Sanders advisor and frequent KHive target.

The KHive is the type of modern political army that politicians increasingly rely on for both support and defense.

“We anticipated the misogyny and racism that she would experience,” said Eric Chavous, an attorney in New York and one of the first to use the hashtag #KHive in 2017, when Harris was a senator and viewed as a likely presidential candidate. “We wanted to make sure there are people out there fighting for her.”

The loose nature of the group — along with Harris’ lack of sharp ideology — has left the network without the strictly defined worldview that identifies groups that have formed around Sanders or Sen. Elizabeth Warren, the Massachusetts Democrat. KHive members speak in favor of racial and gender equality and LGBTQ inclusion and against what they see as an excessively class-based view held by progressives.

But they are not generally advocating for a set of policy briefs. They tend to promote pragmatic liberalism, taking cues from President Biden and Harris about how far Democrats can push legislation and executive action while constrained by a closely divided Congress. Their biggest unifying cause is their belief that they need to push back against Harris’ critics.

“We’re truth-tellers,” said Chantay Berry, a 34-year-old graduate student at Brooklyn College. “We present actual facts. In the hood, you call them receipts.”

Whatever they are, the group, which has no leader or official membership list, is likely to remain an important source of online activism for Harris if she runs for president again.

Though KHive members say they have flourished without direction from Harris, she has embraced them, thanking them at least once on Twitter. Her husband, Doug Emhoff, has at times reached out to members in online comments and phone calls. And when Harris endorsed Biden in March 2020, the two of them made a video in which she explained the KHive to him, saying, “They’re pretty awesome.”

The video ended with Biden asking the KHive for its support. “If I have her team behind me,” Biden said, looking directly into the camera, “I know there’s no stopping us.”

::

The #KHive hashtag first began popping up in 2017, though there is some dispute over its origins. That year, MSNBC’s Joy Reid hosted a panel with Jason Johnson, then with the Root, and Zerlina Maxwell, another progressive host, in which they discussed potential 2020 presidential candidates, including Harris.

Johnson said Harris had “her own Beyhive,” an underestimated group that could be counted on to “protect her and love her to death,” an equivalent, of sorts, to the zealous Sanders supporters known as Bernie Bros.

Reid later tweeted that, after the segment, she and other panelists further discussed Harris’ fervid group of followers and “decided it’s called the K-Hive.”

It was then that Chavous, who tweets as @flywithkamala, began using the hashtag and linking to Reid’s post. He had voted for Sanders in the 2016 primary but since then had read articles comparing Harris and President Obama, and he began to believe she could be president.

“We were encouraging her because we wanted that representation,” he said.

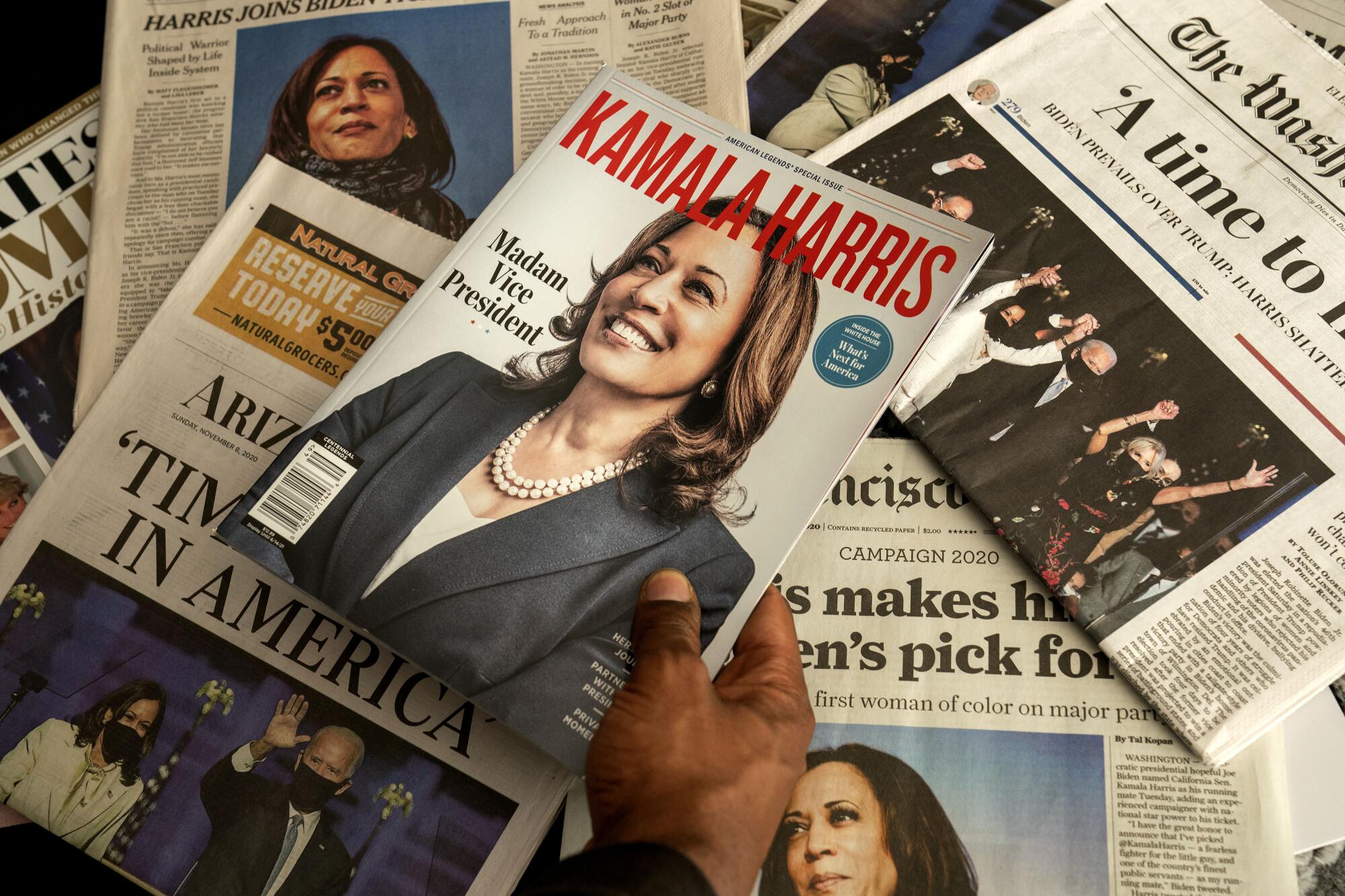

During Harris’ failed run for the Democratic presidential nomination and her successful quest to become Biden’s running mate, the group became increasingly active in producing videos, writing essays and generally pushing back against critics of Harris’ record as a prosecutor and her shift away from supporting Sanders’ “Medicare for all” bill. Later, as speculation began about whether she would try to overshadow Biden if she became his running mate, they aggressively rose to her defense again.

“I wanted them to know I will stomp a hole in you if you come for Kamala, if you come for Black women,” Reecie Colbert, one of the more prominent members, said in an August podcast about KHive with Bakari Sellers. (Colbert declined an interview request for this story but said in an email she was speaking for herself, not the group.) “Kamala needed somebody ... who would gut anybody who came for her, because there were 20 people, hundreds of people as a matter of fact, trying to gut her at every step.’’

Berry, the Brooklyn College graduate student, began making and posting videos in Harris’ defense.

She said she was excited about the potential for a Black female president.

But she has also felt increasing frustration with progressives online, whom she sees as more interested in picking apart ideas than getting things done. Berry ties them to the same forces that have brought gentrification to parts of her native New York, recasting what it means to be progressive.

“The right is going to be just crazy and nuts,” she said. But progressives, if they were truly progressive, “would not disrespect the first Madam Vice President.”

Berry estimates that she spends 30% of her day parsing social media feeds, trending topics and news alerts — writing papers toward her master’s degree in business administration in between. She wears Harris buttons and T-shirts and makes sure to watch all of her television appearances.

Like others in the KHive, she complains about the toxicity of the online world, even as she plays in it. Asked whether she has considered leaving it, she says she has tough skin.

“I’m from Harlem. And so like I’m no punk,” she said. “So you guys are doing this online because I know, in person, you will never approach me.”

Berry, who has about 7,500 followers, recently tweeted a list of progressive leaders who had been critical of Harris, saying they “may go through some things pretty soon.”

Marianne Williamson, a former Democratic presidential candidate and one of 11 names on the list, saw the tweet and responded.

“@KamalaHarris, could you please ask KHive to stand back and stand by?” Williamson tweeted to her 2.8 million followers.

Berry denied she was making a threat, though it looked that way to many people who saw it. Williamson declined to comment.

A Harris official who would not agree to be quoted by name said, “We do not condone harassment of any kind.”

::

Ashley Bryant, a Democratic strategist who specializes in digital marketing, said online factions were likely to play an even bigger role for Democrats in the coming elections, as a means of organizing for the party and determining who succeeds Biden as the standard-bearer. But she called them a mixed blessing, saying she believes that stubborn loyalty to Sanders from some of his most fervent supporters helped Trump defeat Hillary Clinton in 2016.

“You don’t want voters not even being willing to open their eyes to another candidate just because they’re aligned to one that may not get the nomination,” said Bryant, who serves as an advisor to Higher Heights, a political group that supports Black women in politics, including Harris.

Many KHive activists view Sanders’ supporters — fairly or not — as a largely white male set of activists who see the country’s problems through the lens of class, at the expense of race and gender.

“They don’t address the racial inequities,” said DeNiro Jones, a 30-year-old who lives in Dallas and works for an insurance company. “Everything is always centered around Medicare for all. It misses the point.”

KHive members are especially sensitive to criticism from the left about Harris’ record as prosecutor and attorney general of California. Though Harris has at times campaigned as both a “progressive prosecutor” and California’s “top cop,” they resent the latter name and have posted videos defending her role against critiques of her prosecutorial record.

“I can’t speak for everyone but if you check out the video pinned to my profile it goes into detail about the erasure and racism that Kamala Harris has been subjected to by the so called ‘progressive’ left,” said Kenny Walden. The 27-year-old retail worker in North Carolina, who tweets as @2RawTooReal, responded by direct message to questions for this article.

Walden spoke of his frustration with “the constant attacks on her appearance and of all things her laughter,” and the questioning of her “Blackness.”

“So if the Khive seems to be hostile, or toxic we have every reason to be after dealing with the constant misogyny & blatant racism,” he added.

He said many KHive supporters, many of whom are women and people of color, saw themselves in Harris because they, too, had been subjected to unfair attacks in the workplace.

Rep. Khanna, a prominent Sanders supporter who was swarmed by the KHive after pushing Harris on the minimum wage, said he had a good relationship with Harris, taking pride in their shared Indian American heritage, but “I’m going to speak out for my values and convictions, and that’s what a member of Congress is supposed to do.”

He said he engaged online with good-faith critics and criticized his own side when it crossed the line.

“The broader question is, how do we create a social media space that doesn’t reward sensationalism and attack?” said Khanna, who represents Silicon Valley.

Gray, the former Sanders advisor and podcast host, calls Harris’ online fans “politically irrelevant” and says she and others have been the subject of attacks simply for citing Harris’ record, including her prior support for Sanders’ Medicare-for-all bill and her proposal last year to cut Americans checks of $2,000 a month throughout the pandemic. The bill Biden signed into law last month gave one-time checks of $1,400 to most Americans.

“The KHive doesn’t have an ideological agenda,” Gray said. “It’s a fan club where they really, really like Kamala Harris, and they view any political disagreement with her as an attack on her personhood.”

Members deny that characterization. But fandom is certainly part of the culture. Chavous, for example, says he keeps any disagreements he may have with Harris’ record out of his feed.

And Jones says he never leaves the house without some element of Harris attire — a T-shirt, a hoodie or socks. He keeps multiple copies of fashion magazines with her on the cover and has a poster of her on his wall, and he even had the personalized license plate “KLA1AMA” on his car when he lived in Arizona.

He estimates that 90% of his more than 100,000 tweets have been about Harris.

And the KHive has paid him back for that loyalty. When he suffered depression in the fall and could not work, he said, fellow KHivers paid his rent, his car payments, his insurance and his cellphone bill.

“They made sure I have food, they made sure I had clothes,” he added. “And these are people I’ve never met before.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.