Traveling with Trump is a cognitive dissonance carnival

TAMPA, Fla. — The rhythms seem routine, but for those in the “pool,” the small, rotating group of White House reporters who shadow the president, it’s important to note them all.

Air Force One takes off, then lands; a pool report is emailed to other reporters. President Trump takes the stage and says all kinds of things. Then he dances — dances? — as “Y.M.C.A.” plays at max volume. More pool reports. We take off again, and it all repeats somewhere else.

After five years of covering Donald Trump, setting my alarms to his tweets, watching and wondering about him from the 2015 Iowa State Fair to the Oval Office, from New Delhi to Detroit, I was back in the bubble with Trump last week for a final, frenzied campaign swing — three days, six rallies, seven states and almost seven hours of speeches — as he fights for reelection.

Even one hour with Trump can be dizzying. His speeches ramble, his staff frequently is clueless as to his plans, and normal functions often veer toward chaos. The sensory overload can become disorienting, a vaudevillian alternative-reality show — Cognitive Dissonance, the Musical.

Crowds cheer and jeer every incendiary claim, eager to act as props and amplifiers. As he excoriated the media at an event in Lansing, Mich., I looked up to see a woman staring into our enclosure with a mask emblazoned with the words, “The Media is the Virus.” At least she wore a mask.

When you’re surrounded by thousands of euphoric red-hatted supporters, it’s easier to doubt polls that show Trump trailing or tied with Joe Biden in battleground states.

After hearing the same incendiary rally speech six times, it’s easier to grow inured to Trump’s ho-hum denials of a pandemic that has killed more than 230,000 people, his angry calls to stop Americans from voting, the raucous chants to lock his opponents up.

And when you get home, you can’t get “Y.M.C.A.” — the 1970s gay cruising anthem turned global disco hit and now Trump anthem — out of your head.

We started Tuesday in cold rain in Lansing, finishing that night in even more frigid Omaha, where thousands of rallygoers waited hours for buses after we were wheels-up for Las Vegas. Seven people, police said, were hospitalized for hypothermia.

Before returning to Washington late Thursday, we stopped in steamy Tampa, Fla., where more than a dozen people who’d come to cheer Trump suffered from heatstroke and collapsed as he railed onstage about Hunter Biden’s laptop and supposedly dishonest media.

Photos: Election day voting is over but the counting continues.

Metaphors, if you’re looking for them, are often more abundant than masks. Fewer than half of Trump rally attendees, always crowded closely together, usually wear them.

Supporters appear to accept Trump’s breezy assurances that if he could recover from COVID-19 — thanks, he would note, to 12 doctors overseeing his care in the presidential wing at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center and an experimental drug cocktail unavailable to the public — they could too.

His apocalyptic renderings of a Biden presidency, replete with lost jobs and urban unrest, sounded a lot like the current reality for millions of Americans.

“If you vote for Biden, it means no kids in school, no graduations, no weddings, no Thanksgiving, no Christmas and no Fourth of July together,” Trump said Wednesday in Goodyear, Ariz. “Other than that, you have a wonderful life.”

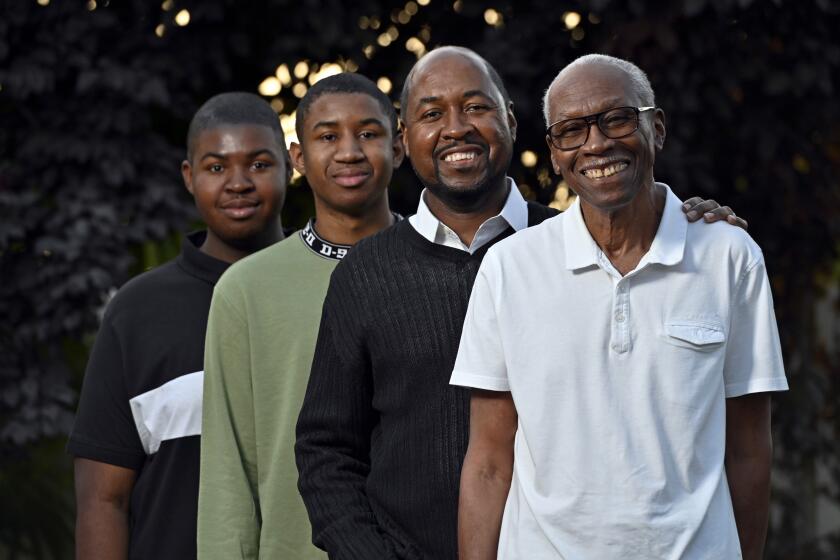

Three generations of a Las Vegas family tell how it feels to be a Black man in America in a season of protest.

The Trump supporters in these crowds don’t care about the gaping holes in his arguments. They don’t mind his coarse behavior. They revel as he toggles between full-throated rage and offhanded sarcasm, exhorting and chuckling, taking selfies and videos, the consummate performer.

Trump’s glib flattery — his campaign sets up big video monitors only at important rallies, he fibs at every stop — is as authentic as professional wrestling. But crowds roar with approval at his jibes and insults, ready to deliver their lines on cue: “Four more years!” “Lock her up!” “CNN sucks!”

When White House reporters take him literally, as we must, we become the butt of the joke, too dense to understand the president’s bond to his supporters — a bond based on identity more than ideology, raw emotion over reason and one that may be unbreakable.

But it goes both ways. When Trump’s at a rally, his hermetically sealed world and the feedback loop it creates gives as much affirmation to the president as he delivers to his fans.

Leaving the stage, he struts across the tarmac to the plane in cold rain or sweltering heat, pumping his fists, determined to look strong. He eschews a ride in the Beast, the black presidential limousine rolling beside him, just in case.

The press pool walks a few feet away, cameras snapping and rolling. The images are a big reason he still holds large rallies in a pandemic — more powerful in Trump’s view than any tut-tutting from Biden, who speaks to smaller crowds at greater distance, chiding Trump for acting irresponsibly.

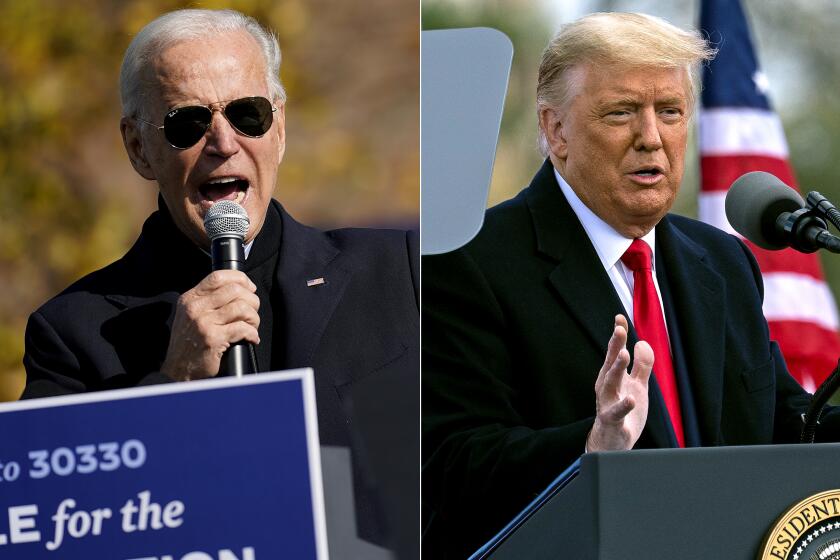

A look at where President Trump and Joe Biden stand on key issues in the 2020 election, including healthcare, immigration, police reform and climate.

Trump is determined to re-create the come-from-behind triumph of the 2016 campaign, visiting as many states as he can, shouting until he is hoarse, even as a majority of voters view his rallies as potential super-spreader events for the coronavirus.

He plans to hold 10 rallies in seven states in the final 48 hours before Tuesday, when voting ends. (Good luck to that pooler.)

Trump has worked assiduously to engineer a last-minute game-changer that might shift attention from the pandemic. It won’t be easy: Half a million coronavirus cases were recorded last week, 99,000 on Friday alone, the most since the pandemic began, and hospitalizations for COVID-19 soared in state after state.

But when the pool got aboard Air Force One on Tuesday, handouts had been placed in our seats promoting an imminent Fox News interview with Hunter Biden’s former business associate Tony Bobulinski. Each handout was scrawled in thick, black marker: “MUST SEE TV!”

As we flew from La Crosse, Wis., to Omaha, White House Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany popped her head into the press cabin and pointed to TV monitors as the interview aired. “You guys should watch,” she said.

But White House efforts to manufacture a scandal around Hunter Biden’s business dealings have fallen flat, mainly because of the lack of credible evidence that Joe Biden was involved.

On Wednesday morning, the pool was ushered into a small ballroom in Trump’s Las Vegas hotel. There was no event on our official schedule, and White House aides said they didn’t know what to expect. Given Trump’s penchant for the big reveal, would he show up with Bobulinski?

But then seven local business representatives walked in, summoned simply to endorse Trump and praise his economic record.

It was a standard event for any other campaign, one with a policy focus and validators for local TV. But it was highly unusual for Trump, who tends to obliterate calibrated messages with real-time reactions to headlines and the bombast he knows will excite a crowd.

The ugliest presidential campaign in modern history could get uglier.

As he stumped that afternoon in Arizona at Bullhead City and Goodyear, he ripped Biden as the leader of a “crime family” and complained that the unsubstantiated scandal wasn’t getting enough attention.

On Thursday in Tampa, he ranted about Miles Taylor, the former Homeland Security chief of staff who’d just outed himself as the anonymous administration official who wrote a 2018 New York Times column blistering the president.

“It’s like a horrible, treasonous, horrible thing that you can do this and you can get away with it,” Trump said about a U.S. citizen exercising his constitutional right to criticize the government.

Reading off the teleprompter, Trump touted the positive news that the nation’s gross domestic product had shot up in the third quarter, a partial recovery from the pandemic-induced economic crash last spring. But he couldn’t stick with it.

“Weekly jobless claims — this is boring, but it’s really good — just hit a seven-month low,” he said.

Polls show Trump has lost many of the suburban women who backed him in 2016, partly over his handling of the pandemic. But his sexism is rarely far below the surface.

Although millions of women lost their jobs, or saw their family finances upended in the pandemic, Trump reassured women in Lansing: “We’re getting your husbands back to work.”

A day later in Goodyear, he called GOP Sen. Martha McSally onstage to make her case for reelection, but needled her as she rushed up the steps, almost apologizing to the crowd for offering time to a lawmaker whose potential defeat could cost his party its Senate majority.

“Just come up fast. Fast. Fast. Come on. Quick,” Trump said. “You got one minute! One minute, Martha! They don’t want to hear this, Martha. Come on. Let’s go. Quick, quick, quick. Come on.”

He placed no time restraints on the three men who followed McSally at the microphone.

Trump’s final, frantic surge of rallies underscore how little the former reality TV star has changed in the White House. These carnivals of passion sustain him emotionally, but may not be enough to sustain his presidency. The narcissism could be self-defeating.

After five years of following Trump, I can hear the frustration in his words, thinly veiled by his anger and professions of confidence, the fear that he may soon become what he hates most of all — a loser.

He’s upset about having to run against Biden, the Democrat who worried him so much that he tried to pressure Ukraine’s leader last year to announce a bogus investigation. That led to Trump’s impeachment by the House, a permanent stain on his presidency.

Leaning against the lectern, Trump tries to chip away at his opponent’s affability, perhaps his main political asset, with brusque, bitter words.

“He’s not a nice guy,” Trump insists, spinning a story about how Biden won the Democratic nomination thanks to help from other candidates determined to bring Trump down, and not because Biden is popular.

“He shouldn’t even be the candidate,” the president groused, seemingly aware there are realities even he is powerless to change.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.