New book by former Trump aide alleges early racist comments

WASHINGTON — Nearly four decades ago, after erecting his eponymous skyscraper on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, Donald Trump would sit behind his rosewood desk and muse about working in an even more powerful office.

“These politicians don’t know anything,” he said. “Maybe I should run for president. Wouldn’t that be something?”

Barbara Res, a longtime executive in Trump’s real estate company, brushed off the idea right up until he was elected president. Now that he’s in the final weeks of his reelection campaign, Res has written a new book titled “Tower of Lies” urging Americans not to give him a second term.

The book recounts racist, anti-Semitic and sexist behavior, along with Trump’s ability to lie “so naturally” that “if you didn’t know the actual facts, he could slip something past you.”

“The seeds of who he is today were planted back when I worked with him,” Res wrote. “He was able to control others, through lies and exaggeration, with promises of money or jobs, through threats of lawsuits or exposure. He surrounded himself with yes-men, blamed others for his own failures, never took responsibility, and always stole credit. These tactics are still at work, just deployed at the highest levels of the U.S. government, with all the corruption and chaos that necessarily ensue.”

The book, a copy of which was obtained exclusively by The Times ahead of its Oct. 20 release, adds to a growing shelf of election-year treatises flaying the president. Trump has been excoriated in print by Michael Cohen, his former fixer; John Bolton, his third national security advisor; Mary Trump, his niece; and Bob Woodward, the veteran journalist.

The President’s “only niece,” clinical psychologist Mary Trump, portrays a man warped by his family in “Too Much and Never Enough.”

Trump’s campaign brushed aside the latest entry.

“This is transparently a disgruntled former employee packaging a bunch of lies in a book to make money,” said Tim Murtaugh, communications director for Trump’s campaign.

In her account, Res wrote that “bigotry and bias control Donald’s view of the world, even the so-called positive stereotypes, which are just as damaging, like saying the Japanese (whom he seems to despise) are smarter than Americans.”

She recalled Trump berating her when he spotted a Black worker on a construction site.

“Get him off there right now,” he said, “and don’t ever let that happen again. I don’t want people to think that Trump Tower is being built by Black people.”

Trump turned red-faced when she brought a young Black job applicant into the lobby of another building, she wrote.

“Barbara, I don’t want Black kids sitting in the lobby where people come to buy million-dollar apartments!”

Res wrote that Trump hired a German residential manager, believing his heritage made him “especially clean and orderly,” and then joked in front of Jewish executives that “this guy still reminisces about the ovens, so you guys better watch out for him.”

Trump and his campaign often pointed to Res during the 2016 election as an example of his progressive history of hiring and promoting women. But during her 18-year tenure, she wrote, Trump talked frequently and graphically about women’s looks and his own sexual exploits — and forced Res to fire a woman because she was pregnant and bar her own secretary from important meetings because she did not look like a model.

While visiting Los Angeles to talk about a potential development, he segued from a discussion of different neighborhoods to how women in Marina del Rey had “tighter asses” than women in Beverly Hills or Bel-Air, Res wrote.

Trump “can’t stand” the working people who make up his political base, she wrote, but “was well aware of the public relations benefit of being liked by ‘the common man,’ and he exploited it, a behavior he continues to this day.”

Res recalled a lavish “topping out” party in 1982 to celebrate the completion of Trump Tower in New York. Trump persuaded the mayor and the governor to show up but balked at allowing the workers to attend, even though, she writes, such parties are typically thrown to celebrate their work.

“Construction workers? I don’t want the construction workers,” Trump said, grudgingly allowing “just the foreman.”

Woodward’s journalism helped bring down Richard Nixon. But “Rage” it too ploddingly neutral and enamored of access to make a dent in this fallen age.

Res has been frequently critical of Trump since leaving the company two decades ago, and she pledged to vote for Hillary Clinton in 2016. She admitted some people may dismiss her experiences because she worked for Trump so long ago, but she said that would be a mistake.

After Res began criticizing Trump during the 2016 election, he lashed out at her, complaining in one speech in San Diego that he gave her “the break of a lifetime” despite warnings from his late father, Fred.

“What Barbara Res does not say is that she would call my company endlessly, and for years, trying to come back. I said no,” he said in a May 2016 tweet that has since been deleted.

If Trump has changed, she wrote, “He’s only become more himself. He is Trump raised to the nth degree, but Trump nonetheless. Donald Squared, I call him.”

Trump hired Res when he was planning his new skyscraper on Fifth Avenue. She recalled visiting his expansive apartment decked out in shades of white — carpeting, couches, tables, drapes — for a job interview as Trump pitched her on the plan.

“It’s gonna be the most talked about building in the world,” he said. Then he added, “I want you to build it.” At the time, Res was a young project manager in the male-dominated New York construction industry.

Trump turned out to be a difficult boss, blaming others for his mistakes, taking undue credit and withholding promised bonuses on a whim. When inspecting Trump Tower during construction, he began screaming at how the marble wrapped around the columns.

“They ruin the atrium and they make me look cheap!” he said.

Trump calmed down when he proposed covering parts of the columns in bronze. Res agreed to the demand but never followed through, and Trump seemed to forget about it.

She called such acts a form of “civil disobedience,” in which staffers would agree to Trump’s “harebrained ideas or outrageous demands” but not carry them out. She also recalled regularly telling subcontractors to give Trump higher prices than they had agreed upon with his subordinates so that Trump could get the satisfaction of bargaining them down.

“Donald had to feel like he had won something,” she wrote.

Those tactics would sound familiar to White House officials, who have tried to manipulate Trump’s ego to soothe him and sometimes hope he forgets his most outlandish directives.

When Trump Tower was finished, his triplex apartment at the top was originally designed in a modern, minimalist fashion. But Res wrote that after he visited Russia’s Winter Palace, the gaudy home where the czar lived, Trump had his apartment redone.

“That’s how it is today, lots of gold leaf and cherubs, wildly excessive, like a child’s version of how a rich person lives,” Res wrote.

She recounts numerous examples of Trump squeezing business partners, the media or the people he worked with, just to get an edge, comparing his recipe for success to a player in the game of Monopoly who has no regard for the rules.

“Imagine if you cheated,” she wrote. “You took money from the bank, skipped spaces, put houses on your properties when no one was looking, and took everyone else’s houses. Would you win?”

After Trump Tower was finished, Res worked on and off for Trump until 1998, at one point serving as his executive vice president for construction and development.

Res said Trump changed over the years. Although always hotheaded and boastful, he became increasingly reliant on yes-men for gratification and addicted to the attention he received.

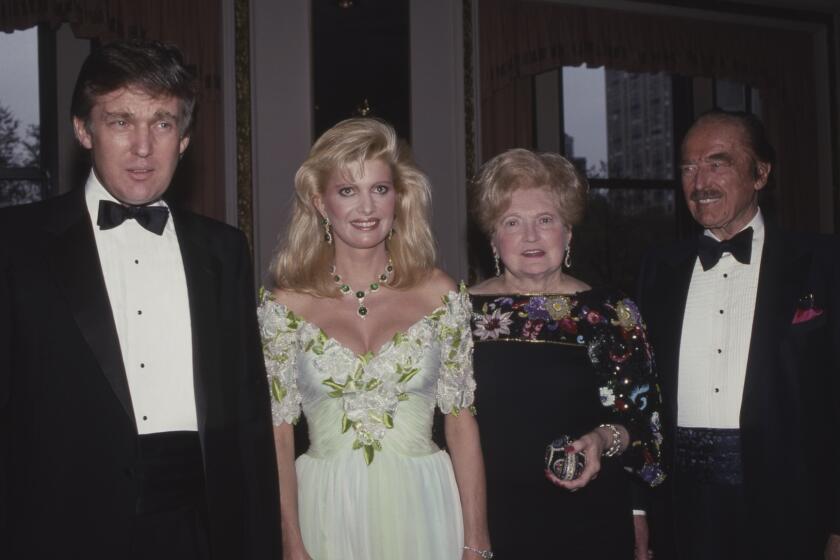

“His regard for himself had increased exponentially, as had his contempt for women,” Res wrote. “His sexism never extended to me, but it did to many others—including his wife Ivana, whom he would publicly belittle — and I came to see that I was the exception rather than the rule.”

As Trump has become increasingly powerful and famous, Res said, his worst qualities have only become more pronounced.

“It’s not hard to look at the trajectory of his entire life and spot an unmistakable pattern: The bigger he got as a name, the smaller he got as a person,” she wrote.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.