Review: The most devastating thing about Mary Trump’s portrait is her empathy for Donald Trump

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Appalled, disgusted, angry, shocked — but not surprised. These are our default reactions to each disgraceful new thing the president says or does, and to any disgraceful new fact unearthed about his past. New pieces of information don’t much alter the portrait.

However, because he might yet destroy our republic and is already the most improbable and spectacular world-historical monster since the chancellor of the German Reich killed himself in 1945, filling in the details remains important. And Mary Trump’s “Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man” is the converse of the standard Trump account — not shocking but definitely surprising.

When I heard that a relative — “my uncle’s only niece,” she calls herself — had written a memoir, my first thought was, How much does any niece or nephew really know? So I was surprised to learn of the multiple annual gatherings she attended, all the encounters entailed in managing a family fortune, and this only niece’s stint as a ghost-writer on Donald Trump’s third book.

‘Too Much and Never Enough,’ a book written about President Trump by his niece, is dark right from the get-go.

Nor did I expect such good, observant writing. Mary Trump crafts both the tragic and comic scenes well. She begins with a great, witty set piece about her visit to Washington for a family get-together in honor of her two Trump aunts’ birthdays. In her room at the Trump International Hotel, “my name was plastered everywhere, on everything: TRUMP shampoo, TRUMP conditioner…TRUMP shower cap, TRUMP shoe polish….I opened the refrigerator, grabbed the split of TRUMP white wine, and poured it down my Trump throat so it could course through my Trump bloodstream and hit the pleasure center of my Trump brain.“ When Jared Kushner finally, briefly joins them in a White House dining room, his wife responds like a Stepford princess: “‘Oh, look,’ Ivanka said, clapping her hands, ‘Jared’s back from his trip to the Middle East,’ as if we hadn’t just seen him in the Oval Office.”

What I expected least of all, however, was the most convincingly empathetic chronicle of Donald Trump I’d ever read.

Mary Trump says she published the book to help “take him down” because “a second term … would be the end of American democracy.” She writes that he tried to get his diminished father to sign a codicil to his will that would’ve screwed Donald’s siblings, and that after he died her uncles and aunts ganged up to screw Mary and her brother out of their fair share. Yet the book is measured, restrained.

There are no fresh examples of his racism, and mainly just general confirmation of familiar misogyny. There are only a few new instances of fraud (that he “paid his buddy” to take his SATs), brutishness (kneeling on his young sons’ backs to win wrestling matches) and ignorance (saying the White House “has never looked better since George Washington lived here”).

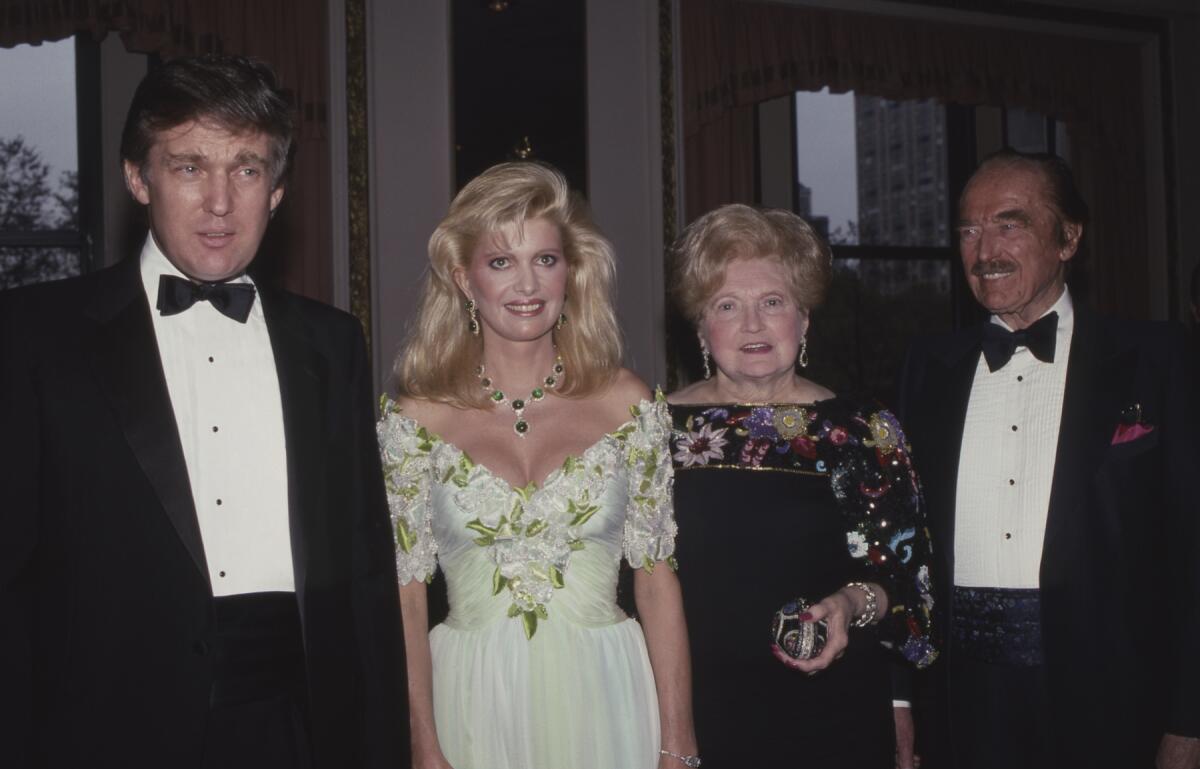

While Mary doesn’t flatter her uncle, she is uniquely equipped to explain why he’s awful: She’s a clinical psychologist who got her PhD after decades of observing him closely, along with three other key characters in this story — her aunt, Maryanne Trump Barry, and her grandparents in Queens. Her basic theory of the case is that Fred, the patriarch of “my malignantly dysfunctional family,” a crude, cruel, selfish, boastful, money-grubbing liar, raised his second son to become a crude, cruel, selfish, boastful, money-grubbing liar. Such an irony: the classic bleeding-heart excuse for criminals’ criminality — childhood deprivation and mistreatment — becomes something of an implicit defense for our gangster-in-chief.

Even though Freud himself co-wrote a biography of a racist who was in the White House when Fred Trump was a child (“Woodrow Wilson: A Psychological Study”), so many bogus psycho-biographies have been published since that they’ve become automatically suspect. There’s also the Goldwater Rule: After a magazine asked thousands of psychiatrists in 1964 if the Republican nominee was “psychologically fit to serve as President,” the American Psychiatric Assn. declared it unethical for shrinks to diagnose public figures unless they’ve examined them. Mary Trump’s decades in the presence of Donald Trump qualify her, and “Too Much and Never Enough” helps redeem the genre.

“Donald’s pathologies,” she says, “are so complex” that arm’s-length diagnoses fail by not going far enough. “I have no problem calling Donald a narcissist — he meets all nine criteria” in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, but she’d also throw in antisocial personality disorder, dependent personality disorder, and some “undiagnosed learning disability that … has interfered with his ability to process information.”

President Trump’s attitude and policies were shaped by neglect and trauma growing up, his niece says in a book released on Tuesday.

Well-to-do from the small fortune Fred’s brothel-keeper father had made, this unhappy Trump family was unhappy in its own way, all five siblings warped by its oppressive frigidity, “but my uncle Donald and my father, Freddy, suffered more than the rest.” In her telling, a critical shift came one night when Donald was 2 1/2. His mother nearly died from post-partum complications, was hospitalized for months and “never completely recovered.” Finally back home, she was … weird — an insomniac “wandering around the House at all hours like a soundless wraith… In the morning her children sometimes found her unconscious in unexpected places.” “Unstable and needy,” she used “her children to comfort herself rather than comforting them.” And so, as a result of his mother’s de facto abandonment and his father’s disengaged failure to “make him feel safe or loved [or] valued,” Donald developed “powerful but primitive defenses” — a willful callousness and “an increasing hostility to others … narcissism, bullying, grandiosity.”

His Rosebud moment comes when he’s 7. At dinner one night he keeps refusing his mother’s and sisters’ pleas to stop tormenting his brother Rob, so teenage Freddy dumps mashed potatoes on Donald’s head. “Everybody laughed, and they couldn’t stop laughing. And they were laughing at Donald,” she writes. “From then on, he would never allow himself to feel that feeling again. From then on, he will wield the weapon.” At her birthday party at the White House 64 years later, Maryanne referred to the incident in a toast, and Donald kept “his arms tightly crossed and a scowl on his face” as, once again, the rest of his family laughed.

His adolescent ripening into a full-bore jerk, right when fun-loving, well-liked Freddy was beginning to escape the family, “finally made my grandfather take notice” and “validate, encourage, and champion the things about Donald that rendered him essentially unlovable.” He followed “the rules in the House,” at least for boys: “be tough at all costs, lying is okay, admitting you were wrong or apologizing is weakness.” Decades later, during his first bankruptcies and first divorce, his mother told Mary that “he was always” a self-pitying brat, and that ”when he went to the Military Academy, I was so relieved.… He never listened to me. And your grandfather didn’t care.”

That’s because, according to Mary Trump PhD, Fred Trump was a “sociopath” who taught his children that his affection for them “was entirely conditional.” One of his explicit conditions for approving of any Trump son was that he be a “killer.” And so Donald’s transgressions “became an audition for his father’s favor, as if he were saying ‘See, dad, I’m the tough one. I’m the killer.’” As when he obeyed Fred’s apparent order to drive up to Massachusetts and whack Freddy, who’d just achieved his dream of becoming a TWA pilot. “You know,” 18-year-old Donald told him, “dad’s really sick of you wasting your life.... He says he’s embarrassed by you ... Freddy, dad’s right about you: you’re nothing but a glorified bus driver.” Freddy promptly became an alcoholic, got canned as a pilot, returned to the family business and ruined his marriage, finally living in his indifferent parents’ attic and dying from heart disease at 42 in 1981.

Former national security advisor John Bolton skewers President Trump and White House insiders in ‘The Room Where it Happened.’

Meanwhile, the “reckless hyperbole and unearned confidence” of his shameless younger brother, masks for “pathological weaknesses and insecurities,” were a perfect match for the manic, money-crazed, celebrity-obsessed perception-is-reality zeitgeist. In the 1980s he turned himself into famous Manhattan developer Donald Trump. But in Mary Trump’s revisionist telling, Fred was not just the funder but the brains of the operation, determined to realize his own big-time real estate dreams before he died. He’d bred Donald to be a killer and (because English was Fred’s second language) a fully American huckster he could use for his own ends. In his early 70s, Fred was “intimately involved in all aspects of Donald’s early forays into the Manhattan market, getting things done behind the scenes while Donald played to the crowd upfront.”

But apart from Donald’s profligacy, he is very much a chip off the old block. Fred, too, “often trafficked in hyperbole — everything was ‘great,’ ‘fantastic,’ and ‘perfect.’” He fostered in his family a permanent “atmosphere of division” that he used to maintain power. As an old man, Fred dyed his hair a ridiculous color. One day 12-year-old Mary was with Fred and Donald when her grandfather opened his wallet. “‘Look at this,’ he had said, sliding the picture out of its slot. A heavily made-up woman who couldn’t have been more than 18 … smiled innocently at the camera, her hands holding up her naked breasts…. ‘What do you think about that?’” She glanced at Donald, desperate for a social cue, but he just “leered at the picture.” When 29-year-old Mary, wearing shorts and a bathing suit, joined her uncle for lunch at Mar-a-Lago, he “looked up at me as I approached ….‘Holy s—, Mary. You’re stacked.’”

Maryanne Trump Barry was a prime source for the book, and not just for tales of “the hell that must have existed inside the House [in Queens] six decades ago.” After her brother announced his candidacy, she told Mary, “He’s a clown. This will never happen … He has no principles. None.” As a rule, useful sources like that get off easy, but not so much here. The New York Times’ 2018 investigation of the family’s untoward financial schemes — for which Mary was a crucial source — implicated Maryanne, a federal judge until 2019. In the book Mary reveals that it was Maryanne who came up with the idea of cutting off health insurance for her and her brother (and infant nephew with cerebral palsy) as punishment for contesting Fred’s will.

After Donald won the election, he phoned Maryanne to ask how he was doing. “Not that good.” “Maryanne, where would you be without me?” “If you say that one more time,” she replied, “I will level you.” He was referring to the story, which the book reports as fact, that she asked Donald to get Roy Cohn to get Ronald Reagan to make her a federal judge.

Mitt Romney and Pat Toomey have stepped up, but the majority on the right are not just willing but thrilled to excuse Trump’s inexcusable commutation of Roger Stone’s sentence.

Now that I experience Donald Trump mainly as a comic-book villain come to life, it was kind of refreshing to read a more fully dimensional portrayal of his origin story. It’s “Succession” crossed with “Death of a Salesman”: bridge-and-tunnel pining for Manhattan success; misery, win or lose; siblings and fathers and cousins double- and triple-crossing each other; tragic as well as funny and even including (as in Arthur Miller) a pathetic cheater son who gets the local egghead to provide test answers. It’s a worthwhile addition to the Trumpological literature. As someone who’s had an off-and-on sideline of exposing and ridiculing Donald Trump for most of my life, however, I’m really hoping we’re finally about to watch the finale of this grotesque, riveting, never-ending show.

Andersen’s new book “Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History” will be published in August. It’s a companion volume to “Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire.”

Too Much and Never Enough

Mary L. Trump

Simon & Schuster: 240 pages, $28

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.