For this reporter, the danger zone is at the White House

WASHINGTON — Anyone who has seen a post-apocalyptic movie knows that a desolate White House offers a ripe backdrop for end times.

That was my overwhelming impression when I reported from the White House this week for the first time since March. Anxiety seemed to lurk at every temperature check and socially distant encounter.

Almost everyone I passed talked about the coronavirus that had infected two staffers in the West Wing, thus breaching the supposedly secure offices and residence of the most powerful man on the planet.

A masked Secret Service agent spoke fatalistically on the phone about her exposure. TV crews and photographers who usually trade pop culture references and practical jokes worried aloud about vulnerable relatives.

Many of the 17 television stalls on the driveway, which normally blast live shots around the world, sat vacant or sparsely staffed. The James S. Brady Press Briefing Room, often crammed with more than 100 chattering reporters, was nearly empty most of the day, and many of the small office bureaus sat dark and abandoned.

Officials in suits still walked briskly across the 18-acre campus, but there were fewer of them. Months after most of the country shut down, the White House last week urged more of its employees to work from home. Only a skeleton staff now comes in.

And while public health officials have pleaded with Americans to wear masks, the White House only directed its staff — from senior national security aides to the cleaning crew — to do so this week.

Some now cover their faces with dark Lycra masks, studded with small American flags or other dressy coverings. President Trump still does not.

Reporters are expected to work in dangerous places. I just never figured the White House to be among them.

But it was my turn on Tuesday to serve as print pool reporter, the eyes and ears for news organizations around the world. The job, which rotates among 31 media companies, is especially crucial in the coronavirus era, when fewer correspondents can safely fit in the cramped 18th century building, and truth itself sometimes seems under siege.

I’m not one of the doctors, ambulance drivers, grocery clerks or countless others who have risked their lives — often for low pay — to help others during this perilous time, and I’m grateful for all they do. I’m also acutely aware that covering the White House is cushy work: I ride on Air Force One and am a witness to history.

Still, going to the White House was unnerving. On May 8, Katie Miller, the spokeswoman for Vice President Mike Pence, and frequently a spokeswoman for the White House coronavirus task force, had tested positive. One of Trump’s personal valets, assigned from the Navy, had tested positive a day earlier.

One after another, senior officials who had contact with them began putting themselves in semi-quarantine. The White House began daily testing for the president, vice president, plus their senior aides and guests. Trump said he and Pence were only speaking by phone in case either was infected.

Mark Meadows, the chief of staff, insisted the White House “is probably the safest place that you can come to.”

I wasn’t reassured. If Trump’s valet caught the virus, who was safe? In the days before my visit, I ground my teeth more than usual at night, and woke from stress dreams about infecting my family.

After weeks working mostly at home, it felt strange to put on a tie and jacket — as well as my mask — and drive down the capital’s semi-deserted streets to 1600 Pennsylvania Ave.

Across the street, Lafayette Park was silent except for a lawnmower. It usually bustles with selfie-taking tourists, office workers and shouting protesters. I saw only one, who apparently lived in his tent, and he had added a handwritten sign to his patchwork of antiwar bumper stickers: “Wash Your Hands! Take Care of Each Other.”

It turned out to be a good day to return. The White House had decided to start daily testing for the 13 print, news wire, radio and television pool reporters, a change from the sporadic tests of the past.

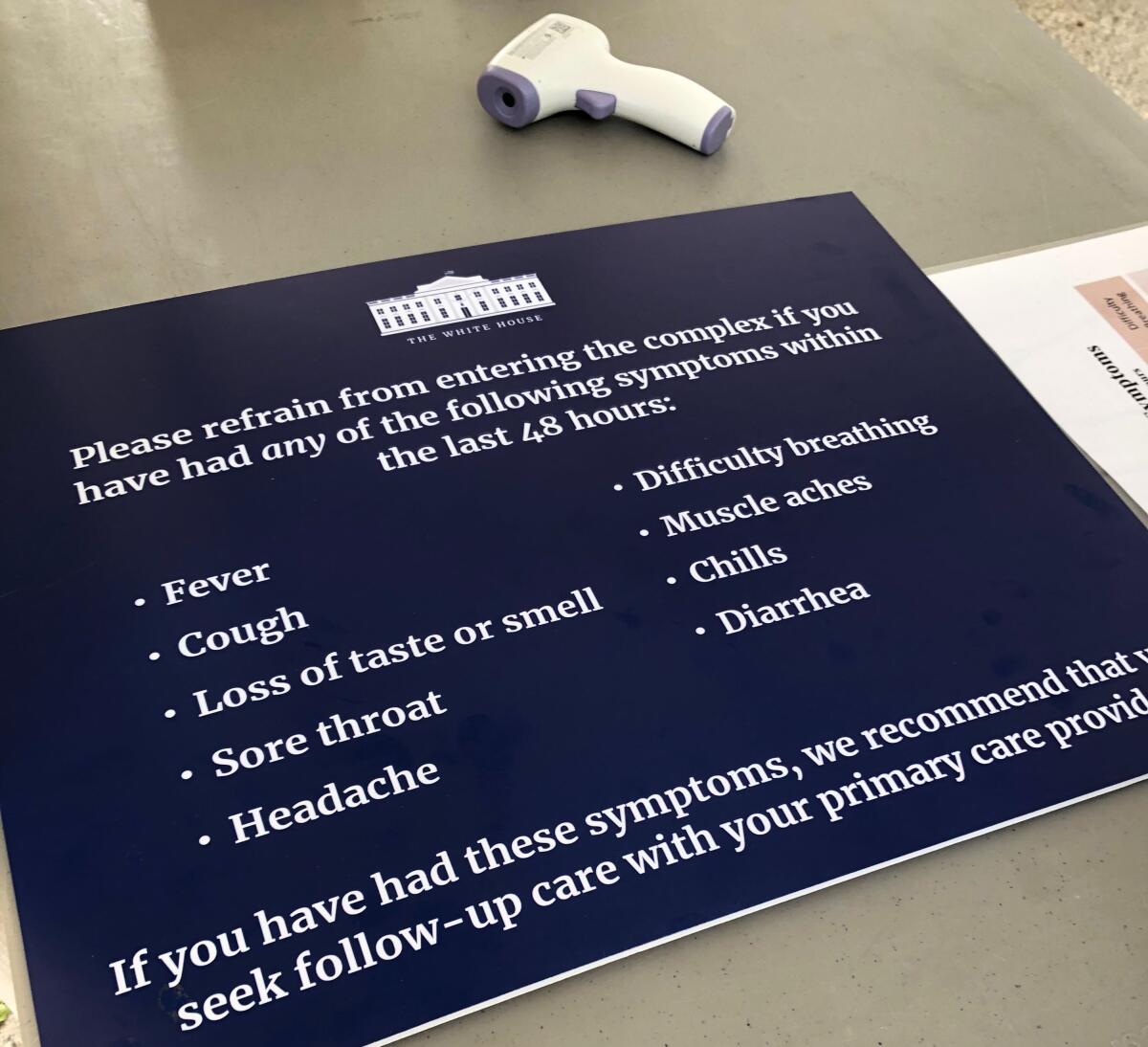

At the security booth, a member of the White House medical unit asked me a battery of questions about my health and took my temperature — twice. She didn’t give me a readout, just an all-clear.

A new sign hung at the Secret Service hutch. “STAY SAFE,” it urged in large type between the White House logo and a reminder to keep six feet from others. “Thank you for practicing social distancing,” it said in small italics.

Mask still on, I passed through the metal detectors, walked down the long driveway and into the back of the press room, where two medics approached me with swabs.

“Three to five seconds, each nostril, sir,” one said.

The swab tickled as it penetrated deep into my nasal cavity. But it did not hurt. I suppressed a sneeze, fearing it would arouse suspicion.

About 45 minutes later, Judd Deere, the deputy press secretary, told me that none of the 13 pool members had tested positive. But it was short-lived comfort.

A preliminary study by New York University, reported by Bloomberg News, found that the Abbott ID NOW test used by the White House may fail to detect as many as half of positive cases.

In addition, a couple dozen journalists who enter the White House press area every day will not be tested daily because they are not in the pool that has the closest contact with the president.

It was a slow day, and I stayed outside as much as possible to avoid mixing with other reporters or touching the doorknobs, furniture or really anything. Though the briefing room looks impressive on television, it’s actually small and dank, built over a former swimming pool.

The reporters’ work spaces can barely fit a laptop. The last time I was print pool, in March, the White House had installed a hand-sanitizing machine next to the pooler’s desk, creating a magnet for passersby.

Good luck trying to keep six feet apart in these conditions.

A Secret Service agent normally mans a desk at the entrance to the West Wing. Now the desk also holds a wooden box of masks, a jug of hand sanitizer and a sign warning those who enter to cover their faces.

Most staffers I saw wore them. The few exceptions included two senior aides who appeared on camera representing the president.

Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany didn’t wear one at her afternoon briefing. She said she did not want her voice muffled on camera and said she kept a safe distance from reporters while at the lectern.

I wasn’t as comfortable. I not only wore my mask. I scrubbed my seat in the briefing room with disinfectant.

Earlier, national security advisor Robert C. O’Brien spoke unmasked to reporters after a Fox Business Network interview on the driveway. He said he would don one when he returned inside.

“We’re doing what we can to socially distance. We’re using hand sanitizer or you’re using a mask on a pretty regular basis, so we’re being as careful as possible,” he said.

The day’s news was in the Senate, where Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top immunologist, was testifying via video link from home because he had self-quarantined after Pence’s aide got infected. Fauci warned of the “danger of trying to open the country prematurely.”

At her press briefing, McEnany tried to square Fauci’s admonitions against “needless suffering and death” with Trump’s claim that “we have met the moment and we have prevailed,” an odd boast given the more than 80,000 American deaths so far.

As the day wore on, anxiety gave way to boredom. Trump spent much of his day tweeting angrily but, in a rarity, did not take questions from the press.

It was cold but sunny outside, and four photographers and a TV crew relaxed on lawn chairs while blasting Van Halen, the Rolling Stones and the Steve Miller Band on an iPhone. They used a silver reflecting umbrella as a sun shield and put their feet up on equipment cases.

A few yards away, another photographer tried to use his iPhone to mimic an announcement on the press room speakers that a “lid” had been declared, meaning the White House planned no more news events for the day and reporters could go home.

If not for the contagion in the building that represents American might around the world, it could have been a day at the beach.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.