Now that the House has impeached Trump, what’s next in the Senate?

WASHINGTON — Now that the House has voted to make Donald Trump the third president ever impeached, attention turns to the Senate, which is tasked by the Constitution with conducting his trial.

If the Senate finds him guilty, Trump would become the first president ever removed from office. That’s highly unlikely.

The Republican-controlled Senate is not expected to convict and remove Trump. But the trial still could be fascinating.

The president didn’t participate in the House impeachment inquiry at all, and the Senate trial is the first time the president and his lawyers will be directly involved.

The House approved two articles of impeachment: abuse of power and obstruction of Congress. They allege that Trump betrayed his oath of office by urging Ukraine to investigate his political rivals after withholding military aid from the U.S. ally, and that he attempted to block Congress from investigating the alleged scheme.

Is this actually a trial?

Yes, but also no.

What is about to happen is called a trial in the Constitution, and it has many elements of a courtroom trial. But it also differs greatly.

Supreme Court Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. will preside and the 100 senators will act as jurors. Conviction requires a two-thirds majority. With 47 Democrats and independents expected to vote for conviction, the question is whether 20 Republicans will join them. The odds of that appear close to zero.

Indeed, impeachment leads to conviction less than half the time. Over the years, the House has impeached 19 federal officials, including two presidents, a Cabinet secretary and a Supreme Court justice. The Senate has convicted only eight of them — all federal judges. It has never removed a president.

There’s a curious twist in the process.

If someone is convicted and removed from office by the Senate, they can be charged in a normal court for a related crime. But impeachment doesn’t require breaking the law.

Section 4 of Article Two of the Constitution says a president can be impeached for treason, bribery or other “high crimes and misdemeanors.” That’s generally seen as severe misconduct in office that violates the public trust, not violating criminal statutes.

What will the trial look like?

The Senate has sole authority to “try all impeachments,” and that means it has pretty broad discretion. The Constitution sets just three real rules. Senators must be under oath, conviction requires a two-thirds majority and the chief justice must preside.

The Senate last updated its written rules governing procedures and practices during non-presidential impeachment trials in 1986. The rules could be changed before the Trump trial, but here’s what they say now.

The trial must take place six days a week until it is completed, and senators must remain completely silent during the proceedings. Senators must submit their questions to the chief justice, and he gets to decide if evidence is relevant or material. Senators can challenge that decision and the full Senate gets to vote.

Trump declined to send lawyers or otherwise participate in the House Judiciary Committee proceedings that produced the articles of impeachment. If Trump similarly chooses not to take part in the Senate trial, it will be conducted as if he had entered a “not guilty” plea.

Will there be witnesses? That’s not yet clear.

Trump says he wants to call witnesses that House Democrats refused to call, such as the still-unidentified whistleblower whose complaint launched the inquiry. Witnesses have testified in some impeachment trials but not others.

If witnesses aren’t called, then what?

Senators could just hear arguments from House Democrats, a rebuttal from the president’s lawyers, and then hold a vote. That’s similar to what happened when President Clinton was impeached in 1998 — and then acquitted in the Senate.

Some Republican leaders like that approach. An impeachment trial stops the Senate from getting other things done and members don’t want to dedicate too much time to something when the outcome is unlikely to change.

When will it start?

That’s not decided. The Senate hasn’t released its calendar for January. There’s talk of starting the week of Jan. 13, but it’s not certain.

How long will it last?

We don’t know that yet either. Frustrating, huh?

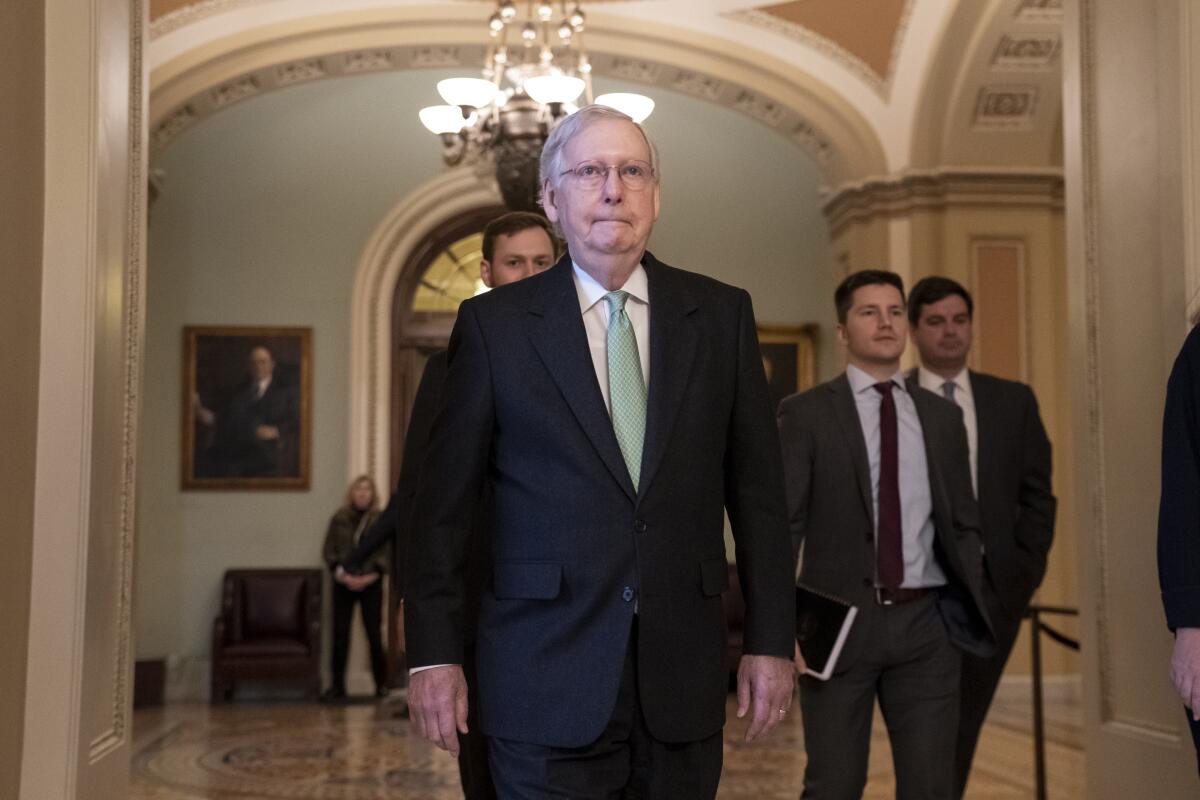

Both of those answers are technically up to a majority of senators, but really it’s up to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and Senate Democratic Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.).

Schumer asked McConnell to call four witnesses, including acting White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney and former national security advisor John Bolton. Schumer proposed starting the week of Jan. 6 and allowing up to 126 hours of statements, testimony and deliberations — meaning a trial of at least three weeks.

McConnell largely shot down that request and suggested he wants a short trial without witnesses. But he also said he would work closely with the president. Trump has gone both ways, saying he wants lots of witnesses — just not those the Democrats want — but is willing to defer to McConnell.

What’s the oath?

The oath senators must take has remained largely unchanged since 1798, according to the Congressional Research Service.

As laid out in Senate rules, each senator will stand and recite this oath: “I solemnly swear (or affirm) that in all things appertaining to the trial of the impeachment of Donald J. Trump, now pending, I will do impartial justice according to the Constitution and laws: So help me God.”

Who will present the Democrats’ case in the Senate?

A handful of representatives will serve as “House managers,” or essentially, as the prosecutors in the Senate trial. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) gets to choose them, but has not done so yet.

They will make opening and closing arguments, could call witnesses assuming witnesses are allowed, and will present evidence.

Can we watch the Senate deliberate?

Sadly, no. Just as a jury deliberates in secret, the full Senate debates the merits of impeachment behind closed doors. They then return to open session to vote on each article separately. They also can choose not to rule on an article.

When it is time for a verdict, the chief justice will call each senator individually to stand and answer guilty or not guilty.

If the president is convicted of even a single article he is removed from office.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.