Column: How will the refusal of GOP senators to convict Trump look to future voters?

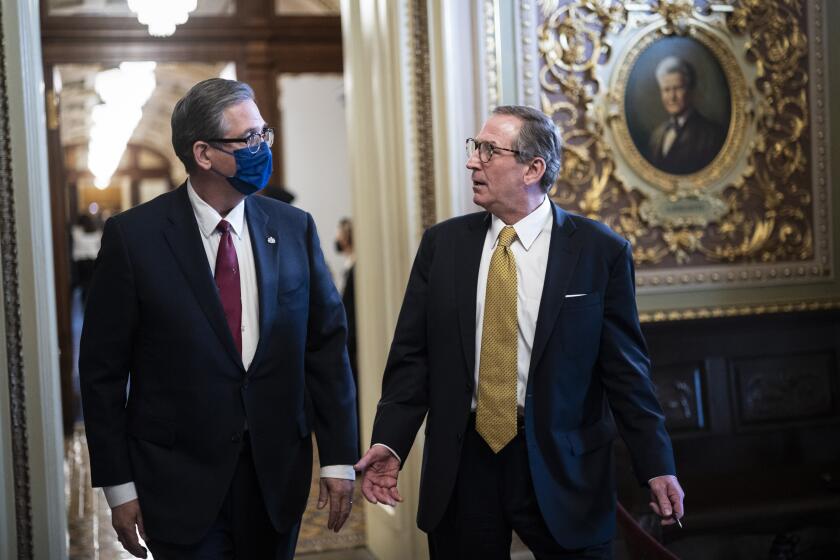

It always seemed unlikely that Sen. Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the Senate Republican leader, would vote to convict the disgraced ex-president who, even from exile in Mar-a-Lago, holds sway over most of his party.

But the justification McConnell offered when announcing his vote for acquittal Saturday was an act of political cynicism and a weaselly evasion of the main issue the Senate was asked to decide: whether Donald Trump bears responsibility for the sacking of the Capitol on Jan. 6.

McConnell has already said what he thinks about the facts: Trump is guilty of incitement, at least under a common-sense definition of the word.

“The mob was fed lies,” McConnell said in a Senate speech last month. “They were provoked by the president and other powerful people, and they tried to use fear and violence to stop a specific proceeding” — the certification of President Biden’s election — “which they did not like.”

For the usually sphinx-like McConnell, that was a moment of stunning clarity — as close to an act of courage as we’ve seen lately in a party whose members are alternately enthralled or terrified by Trump.

Senators’ bipartisan 57-43 guilty vote Saturday fell short of the threshold to convict President Trump of inciting last month’s Capitol insurrection.

But McConnell then retreated, voting to spare Trump from being held accountable — not because he is innocent, but on narrow procedural grounds.

“While a close call, I am persuaded that impeachments are a tool primarily of removal, and we therefore lack jurisdiction,” he wrote to other senators before the vote.

Even though Trump was impeached when he was president, McConnell argued, he cannot be put on trial after the end of his term.

Most legal scholars, conservatives and liberals alike, believe that argument is wrong. In past centuries, the Senate has tried at least two officials who were no longer in power. And last week, by a bipartisan vote of 56 to 44, the Senate upheld those precedents.

The motive for McConnell’s retreat is clear: He wants to give his Republican colleagues a cover story, a technical excuse to vote against impeachment so it doesn’t come back to haunt them. Most Republican primary voters remain loyal to Trump, often fiercely so.

But the reason McConnell is providing is so flimsy that it’s unlikely to stand up well in the eyes of history.

McConnell’s dodge wasn’t the only weak excuse GOP senators reached for as they searched for reasons to acquit a defendant many of them privately believe to be guilty.

Some engaged in old-fashioned tit for tat: Sure, Trump riled up the mob, but didn’t some Democrats do the same thing when they made excuses for violence on the fringes of Black Lives Matter protests?

“You had a summer where people all over the country were doing similar kinds of things,” Sen. Roy Blunt of Missouri said. So what’s the big deal about Trump encouraging the people who sacked the Capitol and threatened to kill the vice president?

Equally weak was the assertion that the impeachment was “just politics,” a product of hatred for Trump and his followers.

“This is about humiliating the individuals that supported President Trump,” Sen. Marsha Blackburn of Tennessee argued.

Leave aside that 10 House Republicans, including Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming, considered the charges serious enough that they joined Democrats to vote in favor of impeachment.

Then there’s the 1st Amendment argument: the notion that holding Trump accountable for the effect of his words is a violation of his rights.

That’s simply wrong. The 1st Amendment protects Citizen Trump’s right to speak his mind. It doesn’t protect former President Trump from losing his job — or being barred from holding it again — if Congress decides that he has committed crimes against the Constitution. And the 1st Amendment doesn’t protect incitements to violence.

And that brings us to the substantive charge against Trump — the one Republicans keep trying to evade.

The evidence has made it clear that Trump not only encouraged the mob; when they rampaged through the Capitol, he waited hours before telling them to go home.

The president’s defenders want senators to judge Trump’s guilt of incitement under the standard of criminal law, which requires showing that he knowingly and directly caused the riot.

But impeachment isn’t a criminal proceeding. It’s the process by which Congress can remove a high official who has violated his oath and disqualify him from holding office in the future.

The senators who voted to acquit need to say clearly whether they believe Trump incited the mob or not. McConnell said Trump was “practically and morally responsible” for the events of Jan. 6 but let him off on a technicality. Most other Republicans haven’t even gone that far.

History will remember their votes as their judgments on Trump’s words and actions — not as a decision about whether officials are exempt from impeachment trial for actions in their final month in power.

They should consider how their short-term political calculation may look years from now, including to voters in coming elections.

On Saturday, Trump claimed his acquittal as a victory and promised his followers that he will remain politically active. “Our historic, patriotic and beautiful movement to Make America Great Again has only just begun,” he said.

In the months ahead, new evidence may emerge to show whether Trump connived directly with the extremists who assaulted the Capitol. As we heard Saturday, Trump seemed unconcerned that members of Congress were in mortal danger that day.

And if Trump survives all the investigations into his conduct, maintains his grip on the GOP and wins his party’s presidential nomination in 2024, his loyalists in the Senate will bear responsibility — even though they may pretend it wasn’t their doing.

McConnell, no fan of Trump, seems to be gambling that the former president will naturally fade away and that his hold on the Republican Party will weaken. He and the GOP have to hope they’re right.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.