Think Warren’s too liberal? Biden’s old news? Midwesterners Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar want to talk to you

SIGOURNEY, Iowa — Just when it looked like the Democratic presidential contest was becoming a two-person race, a pair of Midwestern pragmatists are betting they can still rise by speaking to an unsatisfied slice of the electorate: voters who believe Sen. Elizabeth Warren is too far to the left but think former Vice President Joe Biden is yesterday’s news.

Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Ind., has been building a robust campaign infrastructure and raking in piles of campaign cash, and during last week’s debate he grabbed the spotlight with an aggressive challenge to Warren.

“My lane has never been clearer,” he told reporters after speaking Friday at the University of Chicago. “If you want the left-most-possible candidate, you’ve got a clear choice. If you want the candidate with the most years in Washington, you’ve got a clear choice. For everybody else, I just might be your person.”

Sen. Amy Klobuchar also got a boost from the debate, where she gave her most effective pitch yet for being a pragmatic Midwestern alternative to the liberalism of Warren and Bernie Sanders. Vermont Sen. Sanders has been coming in third in most polls of late, but he moved to rekindle his campaign after his recent heart attack with a big rally in New York on Saturday.

Klobuchar took her post-debate campaign push to Iowa for an 11-city, three-day bus tour of the state.

“I don’t see this as flyover country. I see this as home,” the Minnesota senator told voters gathered in an Iowa home-decor store on Friday in Sigourney, about 80 miles east of Des Moines. “A lot of people make a lot of promises, especially to Iowa. What really matters is their track record.”

Both long shots are now trying — with swings through early-voting states, new ads and endorsements, and intensified fundraising efforts — to keep their post-debate sizzle hot and find an opening in the contest that has been shaping up as a showdown between Biden and Warren.

In the process, they are surfacing a long-simmering debate about the dominance of the party’s liberal wing on the East and West coasts — making a more pointed case than Biden, whose campaign pitch builds on his experience more than ideology.

“It’s the Midwest versus the rest of the country,” said Rufus Gifford, who was finance director of President Obama’s reelection campaign in 2012 and is uncommitted in the 2020 race. “Both Pete and Amy really focused on the fact that this is the part of the country we need to win, and we are losing.”

The two have been easy to overlook because both have been stuck in single-digit ratings in most national and early-state polls. But even before the debate, several polls showed Buttigieg moving into a stronger fourth-place position, behind Warren, Biden and Sanders. Some Iowa polls have even shown him edging into third place ahead of Sanders.

Of course, splashy debate moments don’t often have lasting impact, as Sen. Kamala Harris of California found after the first Democratic debate. Her well-scripted criticism of Biden’s record on segregation and school busing produced a sharp spike in polling and fundraising, but it quickly faded, and Harris has never recovered.

Buttigieig is far better equipped — than Harris was then and Klobuchar is now — to propel his debate moment into campaign momentum. He has far more money and a bigger campaign organization in early-voting states, especially in Iowa. Buttigieg’s campaign says it has more than 100 staffers in Iowa and 22 field offices. Klobuchar’s operation is half the size.

Buttigieg has had fundraising success that outstrips his standing in polls. He has raised more than $51 million this year — third behind Sanders and Warren — and he has $23.4 million still on hand, compared with Biden’s $9 million. Klobuchar has raised less than $18 million all year, including a $3.5-million transfer from her Senate campaign, and has $3.7 million in the bank.

But Buttigieg also has unique vulnerabilities: He is a boyish-looking, 37-year-old gay man whose only governing experience is as mayor of a city of just over 100,000.

“If he was governor of Indiana and 10 years older, he’d be our nominee,” said Gifford. “The challenge is, he is 37 and mayor of a small city. That leap is tough for a lot of people.”

To capitalize on the buzz from his debate performance, Buttigieg is taking a swing this week through all four early-primary states, including Nevada, New Hampshire and South Carolina. The day after the debate, Buttigieg went to Ames, Iowa, for a bit of a victory lap.

“Who saw the debate last night?” Jessica Reynolds, a Story County prosecutor who endorsed and introduced Buttigieg, asked the crowd at Iowa State University. “Didn’t he knock it out of the park?”

Admitting to being “a little sleep-deprived,” Buttigieg portrayed himself as less divisive, but no less bold, than his rivals.

“I will put forward ideas that are bold enough to solve the challenges that are in front of us, and do it in a way that can unify the American people,” he said. A central focus of his campaign — and his debate attack on Warren and Sanders — has been healthcare. Whereas they propose replacing the current system with a Medicare program that covers all Americans, Buttigieg would allow people to opt into Medicare or keep their private plans.

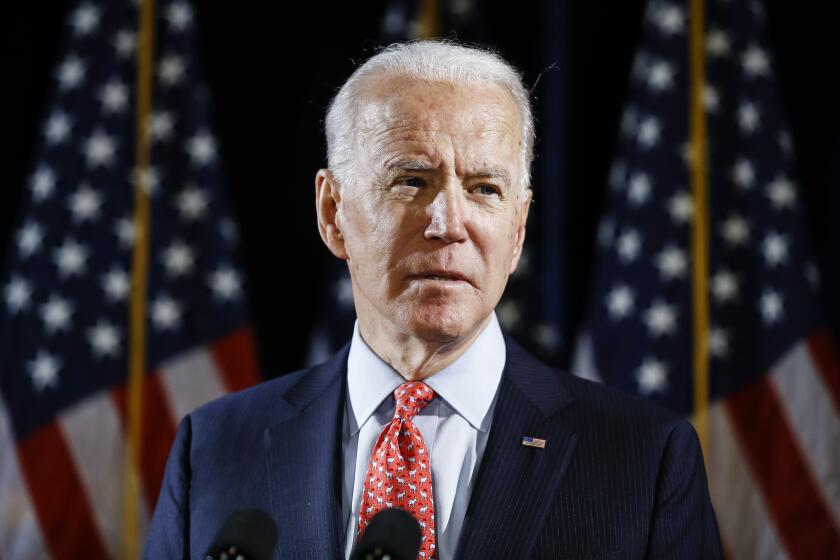

The field is down to Joe Biden now that Bernie Sanders ended his presidential campaign. Here is the Democrat heading for a battle with President Trump.

Asked what it would take to keep his post-debate momentum going, Buttigieg said his team would be taking his middle-of-the-road message to the many undecided voters in Iowa and elsewhere.

“There are clearly a lot of voters right now who are still dialing in,” he told reporters in Chicago. “We need to make sure that voters who like the idea of ‘Medicare for all,’ but hate the idea of giving up their private plans, let them know I’ve got the right plan for them.”

Preparing to spread the word, more than a dozen volunteers gathered Friday night at a Buttigieg field office in Ankeny, a suburb of Des Moines, with a sense of urgency.

“It’s really important because after the debates we’re seeing all this crazy energy, and we want to harness that,” said Shannon Sankey, a 23-year-old organizer for the campaign. “And the best way we can do it is knock on doors.”

Buttigieg’s supporters seem comfortable with his more combative tone, even though it is a big shift for a candidate who has called for a positive, unifying campaign. Jacob Sher, a University of Chicago student, believes it is time for Buttigieg to come out swinging.

“I love how he went on the offensive in the debate,” Sher said while waiting to hear Buttigieg speak on campus. “Some people might have seen it as off from his original message, but in order to be a strong contender, it was a necessary move.”

Some analysts see Buttigieg as a kind of understudy for Biden, well positioned to advance if the former vice president falters.

But he differs from Biden in one troublesome respect: He has failed to draw significant support from African American voters, who have been central to Biden’s polling lead. Early in the campaign, Buttigieg aced criticism back home for his handling of racial tensions in South Bend over a police shooting of a black man.

On Friday, reports surfaced that a Chicago fundraiser for Buttigieg was being co-sponsored by a city official who in 2014 tried to block release of a video showing the fatal shooting of a black teenager by a Chicago police officer. Buttigieg responded by cutting ties with the donor and removing him as sponsor of the event. “I’m going to figure out how it happened and make sure it doesn’t happen again,” he told reporters.

For Klobuchar, the debate provided an especially welcome windfall, as donations totaling more than $1.1 million came in 24 hours. That’s about the same as Buttigieg’s post-debate haul, but it means more to Klobuchar’s shoestring campaign.

“That’s a big deal. When you look at our total, that’s going to be a big boost for us,” Klobuchar told reporters on her campaign bus Friday morning, noting that she did not have enormous fundraising lists like the front-runners, two of whom had run for president before.

“I would love to be running millions of dollars of ads like some people can buy right now. I have to be frugal,” she said. “I know that a lot of people don’t know who I am still. And that’s on me. I’ve got to do whatever I can with our limited resources to get that out there.”

California billionaire Tom Steyer spent $47 million during the first three months of his Democratic presidential bid. The sum places him on track to join the biggest self-funding political candidates in U.S. history.

Like most candidates in the back of the pack, Klobuchar is staking everything on Iowa, whose Feb. 3 caucuses kick off Democrats’ nominating contest. A resident of a neighboring state, Klobuchar has held more events in Iowa than any candidate but long-shot former Rep. John Delaney of Maryland, according to a tally kept by the Des Moines Register.

But a September Des Moines Register/CNN poll found that just 3% of likely caucusgoers supported her, and 26% didn’t know enough about her to have an opinion. Her sparse campaign organization limits her ability to quickly capitalize on her post-debate momentum.

Klobuchar kicked off her Iowa tour by rolling out endorsements by state lawmakers, including Rep. Andy McKean, who had been the longest-serving Republican in the state Legislature until this year, when he left the GOP over objections to President Trump and became a Democrat.

“She has that practical, common-sense, Midwestern approach that I think will resonate very favorable with the people of Iowa,” McKean said.

Many who are considering backing her say they are drawn to her pragmatism and see Klobuchar, 59, as both a more mature alternative to Buttigieg and a more youthful, female alternative to Biden.

“He’s past his prime, ” Dan McGuire, a Des Moines surgeon, said of Biden, adding that Buttigieg is “a little young — he hasn’t quite shown that he gets things done.”

Klobuchar is the “just right” candidate between them, he said.

“She has a pretty proven track record in the Senate of getting things done,” he said. “Not so much saying but getting them done.”

Mehta reported from Iowa and Hook from Washington, D.C., and Chicago.

Here are key dates and events on the the 2020 presidential election calendar, including dates of debates, caucuses, primaries and conventions.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.