Black residents of South Bend unload on Mayor Pete Buttigieg

Reporting from South Bend, Ind. — A town hall featuring Mayor Pete Buttigieg broke into near chaos Sunday afternoon as the Democratic presidential candidate tried to respond to community anger over a white police officer’s killing of a black man.

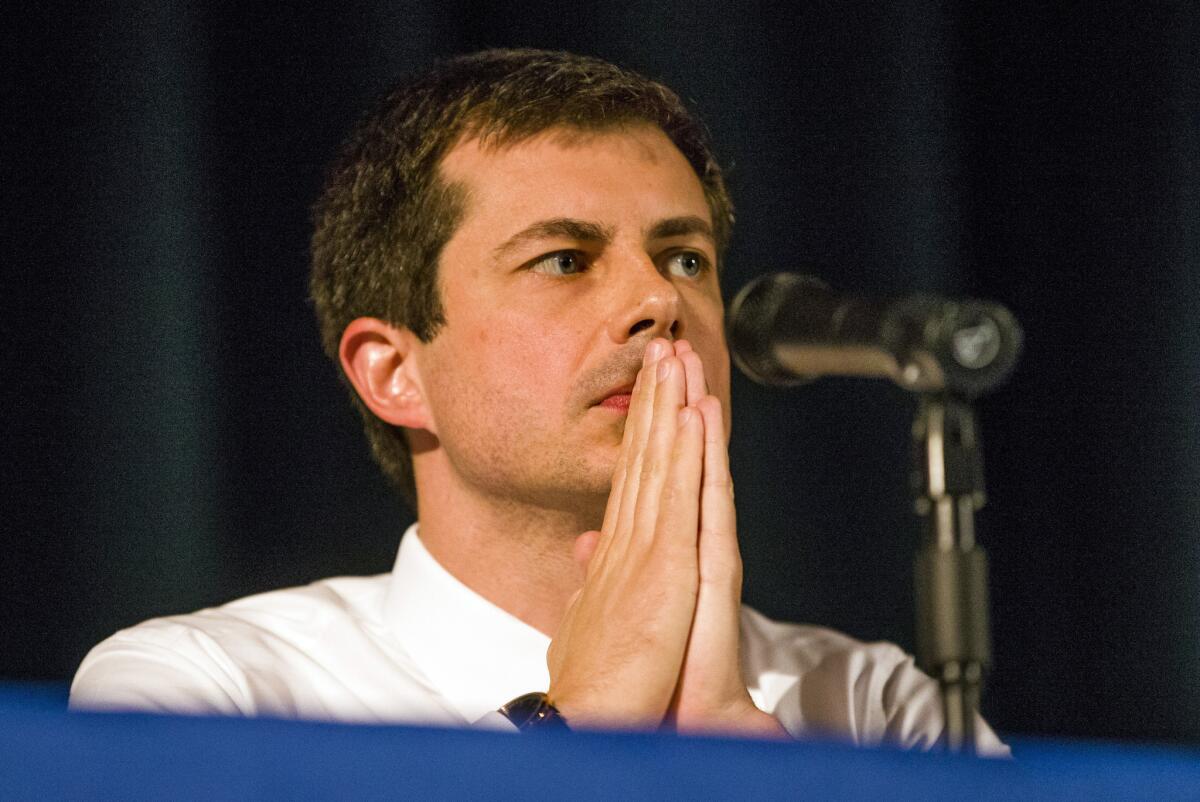

Buttigieg was solemn, somber and circumspect as he tried to explain how officials will investigate the shooting. He said he would ask the Justice Department to review the case and for an independent prosecutor to decide whether to prosecute.

“We’ve taken a lot of steps, but they clearly haven’t been enough,” said Buttigieg, who is in his second term as mayor of South Bend, Ind.

The largely black audience of hundreds was having little of it, frequently interrupting and shouting over the mayor. “We don’t trust you!” a woman hollered at Buttigieg.

The tragedy unfolded in Buttigieg’s hometown on June 16, and it would be difficult to imagine a domestic crisis more nightmarish for a mayor and a presidential candidate who has enjoyed a largely carefree rise to the top tier of Democratic contestants.

Buttigieg’s lack of popularity among black voters nationally — a crucial demographic for winning the Democratic primary – was already one of his biggest weaknesses in a contest in which racial injustice is a key issue. Buttigieg had recently been laying the groundwork to win over some of those skeptical voters in states such as South Carolina.

But now the shooting has highlighted the racial tension right on Buttigieg’s home turf, revealing for a national audience the pain and resentment that have long festered among South Bend’s black residents.

Buttigieg’s introduction drew a mix of applause and vigorous boos. Michael Patton, NAACP South Bend Chapter president, was onstage with Buttigieg and lobbed gentle questions at the mayor, which drew loud complaints from the crowd. But audience members sometimes scolded one another for being disrespectful to Buttigieg and the other speakers.

When a pastor representing Al Sharpton Jr. was the first from the audience to take the mic during the town hall’s question-and-answer portion Sunday, the crowd jeered at the outsider. John Winston Jr., a community activist, walked up to the front of the stage to confront the pastor as Buttigieg watched, taking the microphone to air his own grievances about the city’s relationship with its black residents.

“They keep begging us to reach out and bridge this gap and whatever else,” Winston, who is biracial, told the audience, recounting the time he tried to host a cookout for police officers a few years ago. “And we reached out, and they said no.”

Then, with a defiant flourish, Winston dropped the mic onto the floor.

Activist John Winston Jr. addresses the audience and Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg during a town hall Sunday in South Bend, Ind.

Until now, Buttigieg had enjoyed a charmed and improbable role in the presidential primary as the surging mayor of a Rust Belt city whose population barely tops 100,000, a 37-year-old in a field dominated by two 70-somethings.

He’d been lifted in the polls — and into television green rooms — by his gifts as a communicator and by his singular biography as an openly gay veteran who reads James Joyce and speaks several languages.

His mere existence as a liberal force in conservative Indiana suggested an alternative path for Democrats fighting to rebuild support in the nation’s heartland.

But at home, Buttigieg is a much more common figure in American politics: a white politician struggling to connect with his black constituents, many of whom are plagued by grinding poverty and violence that their wunderkind mayor has been unable to eradicate after seven years in office.

“You might as well just withdraw your name from the presidential race,” said a woman in the raucous crowd. “His presidential campaign is over... I believe that today ended his campaign.”

South Bend police said that Sgt. Ryan O’Neill shot Eric Jack Logan, 53, in the parking lot of an apartment complex. O’Neill was responding to reports of cars being burglarized. When he approached Logan, he said, the man threatened him with a knife.

The sergeant didn’t turn on his body camera as required, leaving black residents, already skeptical of their police department after past controversies, in doubt of the sergeant’s side of the story.

Even before the tensions in South Bend became news, Buttigieg’s campaign rallies and town halls in predominantly black neighborhoods around the country had attracted mostly white voters. Buttigieg has tried to bolster his support from black voters with events such as a much-publicized fried-chicken lunch with Sharpton in Harlem.

“Black voters have more of a wait-and-see attitude than a lot of other Democratic voters when it comes to evaluating white candidates,” said Ron Lester, a pollster with decades of experience surveying black voters. “They have an inclination to support candidates they know and they can be very stubborn about changing their minds.”

Buttigieg’s response to the police shooting in South Bend, said Bill Carrick, a Democratic strategist who is neutral in the party primary, will be closely scrutinized because of its relevance to the presidential contest.

“The nature of criminal justice in America is a really big part of the campaign,” he said. “People will make a judgment about him based on how he handles this.”

Buttigieg is not alone in waging defensive maneuvers over his record.

Joe Biden, who was the vice president under Barack Obama and who enjoys great support among African Americans in the Democratic primary, has been attacked by some for working with segregationist lawmakers and voting for the 1994 crime bill. Sen. Kamala Harris of California, who is black, has faced questions whether she fought hard enough against mass incarceration as a prosecutor.

While running as a mayor has allowed Buttigieg to skip some of the usual steps on the way to the Oval Office — like, say, winning a statewide office first — being an executive also has its downsides.

Unlike members of Congress, who can spend long stretches away from the job without being missed, mayors and governors are on point and get held accountable for all of the many things that can go wrong in their absence, be it natural disaster, a police shooting, municipal strike or other calamity.

Buttigieg has canceled many campaign events and met with community members since the shooting. But his decision to slip away to the South Carolina Democratic Convention for a speech on Saturday created a sense among some residents that Buttigieg’s attention is elsewhere.

“You went to South Carolina when you got something here in your own city,” said Komaneach Wheeler, a 39-year-old community activist, who added with mock wonder in her voice: “Why don’t you want to talk to us?”

Buttigieg was also heckled when he met earlier in the week with black residents. The confrontation was televised on CNN.

The shooting victim’s mother publicly chastised the mayor. “I have been here all my life, and you have not done a damn thing about me or my son or none of these people out here,” Shirley Newbill told Buttigieg. “It’s time for you to do something.”

Buttigieg has promised to recruit more officers of color and tighten police discipline standards, though he balked over the phrasing of a petition demanding that the U.S. Justice Department investigate the shooting.

For some black residents, Buttigieg had already failed the biggest chance he had to build trust with the community, back when he was first elected mayor in 2011 as a 29-year-old.

Not long after in 2012, he pushed out the city’s black police chief, Darryl Boykins, over allegations that Boykins improperly recorded white police officials making racist remarks. The crisis unleashed a flurry of litigation that resulted in financial settlements for the officers and for the former chief.

Boykins’ removal, along with the fact that the recordings were never released, have been seen as a kind of original sin for Buttigieg’s mayoralty among some black residents.

Buttigieg “had a chance to make a stand and didn’t do it. He never stepped up and became the leader,” Blu Casey, 23, an activist and recording artist, said in an interview Saturday.

O’Neill, the sergeant, had also previously faced an internal inquiry in 2008 for racist remarks, including the time he referred to an African American woman as “black meat,” according to a fellow patrolman’s account, leading some South Bend residents to question why O’Neill was still working for the department in a city that is 26% black.

“This is the beginning of a conversation that will continue,” a somber Buttigieg told the crowd as the town hall ended.

In a meeting with journalists afterward, Buttigieg said: “You can sense the pain not only around this incident, but around our history, and not only around our history as a city, but what’s happening everywhere that so many black Americans have felt in relation to the police.”

NBC News reported that Buttigieg still plans to take part in this week’s presidential debate in Miami.

Times staff writers Mark Z. Barabak and Michael Finnegan contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.