MEXICALI, Mexico — From the roadside, Oswaldo Ortiz-Luna offered a box of candy to the cars idling in the golden dust of northern Mexico. His wife hawked another box of sweets farther up the line of traffic, perching their 18-month-old daughter on one hip. Sticky fruit and tears smudged the baby’s cheeks.

As the sun went down, Oswaldo and his family of six hadn’t yet sold enough candy for the roughly $6 they needed to spend the night at a nearby shelter. They are among the thousands of asylum seekers trapped just beyond the border under the Trump administration’s signature policy — “Remain in Mexico.”

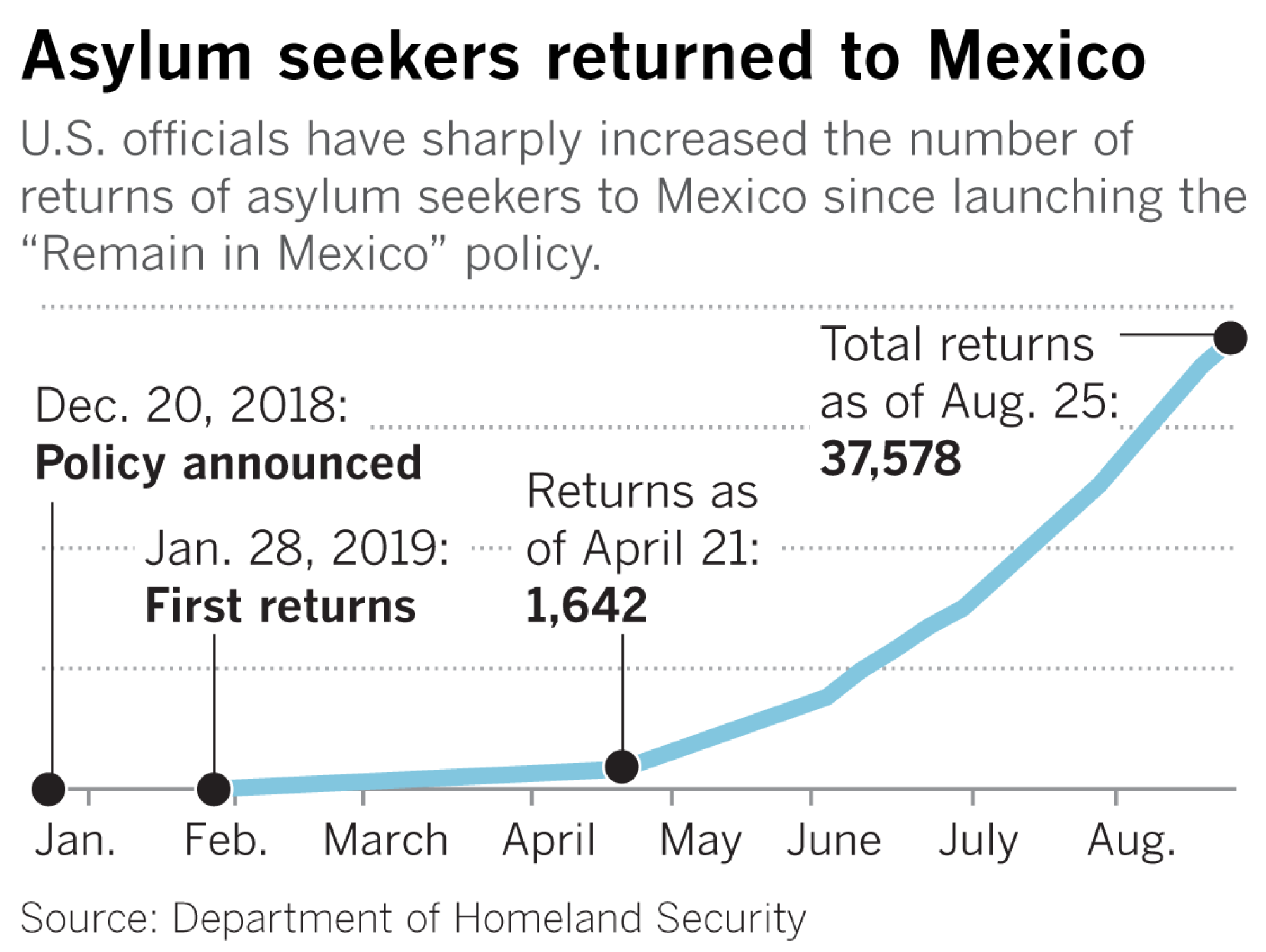

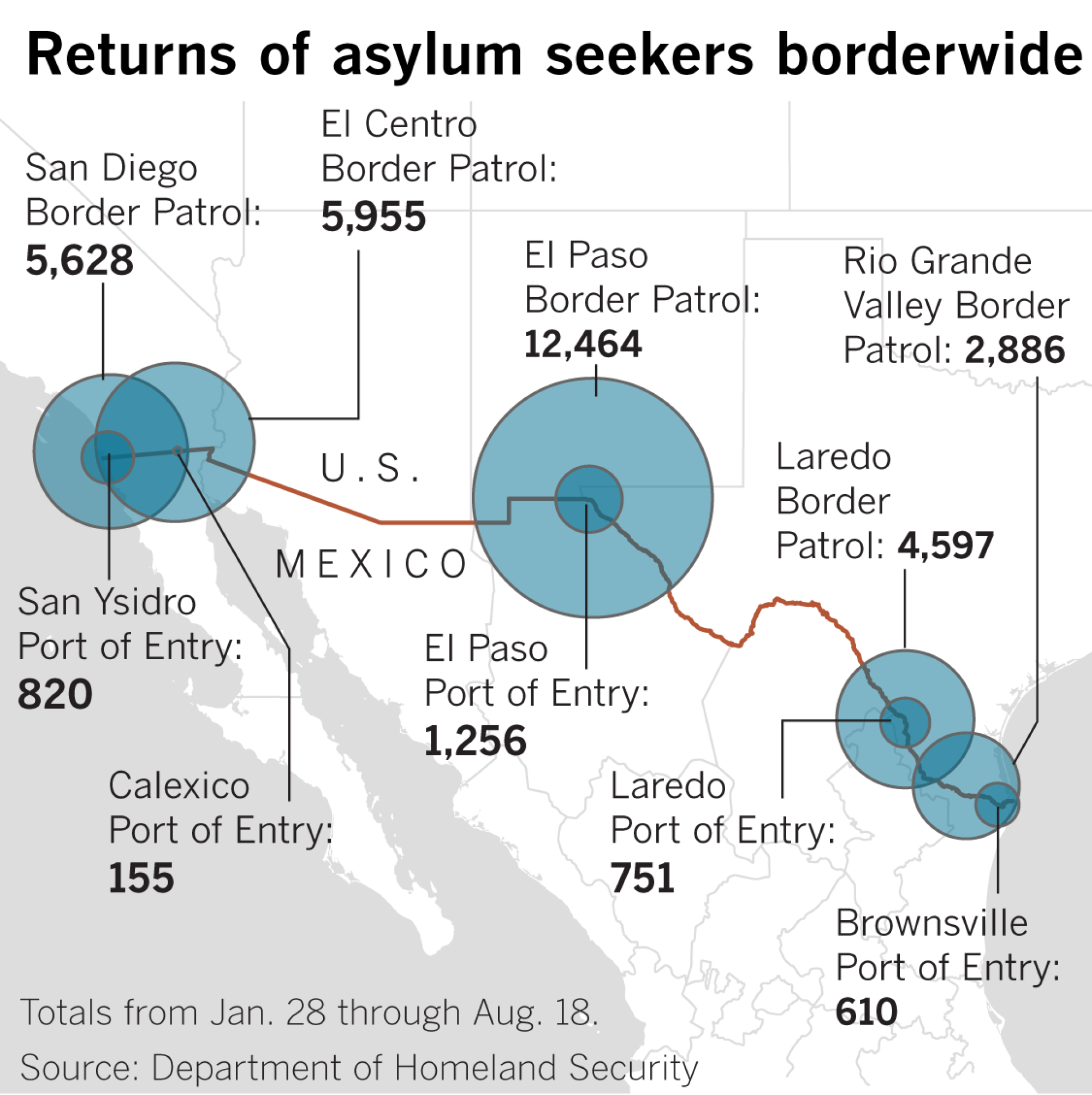

Under the Migrant Protection Protocols — better known as Remain in Mexico — Trump administration officials have pushed 37,578 asylum seekers back across the U.S. southern border in roughly seven months, according to Homeland Security Department reports reviewed by the Los Angeles Times. One-third of the migrants were returned to Mexico from California. The vast majority have been scattered throughout Mexico within the last 60 days.

While their cases wind through court in the United States, the asylum seekers are forced to wait in Mexico, in cities that the U.S. State Department considers some of the most dangerous in the world. They have been attacked, sexually assaulted, and extorted. A number have died.

In dozens of interviews and in court proceedings, current and former officials, judges, lawyers and advocates for asylum seekers said that Homeland Security officials implementing Remain in Mexico appear to be violating U.S. law, and the human cost is rising. Testimony from another dozen asylum seekers confirmed that they were being removed without the safeguards provided by U.S. law. The alleged legal violations include denying asylum seekers’ rights and knowingly putting them at risk of physical harm — against federal regulations and the Immigration and Nationality Act, the foundation of the U.S. immigration system. U.S. law grants migrants the right to seek protection in the United States.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers are writing the phrase “domicilio conocido,” or “known address,” on asylum seekers’ paperwork instead of a legally required address, making it nearly impossible for applicants stuck in Mexico to be notified of any changes to their cases or upcoming court dates. By missing court hearings, applicants can then be permanently barred from asylum in the U.S.

Meanwhile, some federal asylum officers who are convinced they are sending asylum seekers back to their deaths told The Times that they have refused to implement the Remain in Mexico policy at risk of being fired. They say it violates the United States’ decades-long legal obligations to not return people to persecution.

Homeland Security headquarters, as well as Customs and Border Protection, the agency charged with primary enforcement of the policy, refused repeated requests for interviews or data on the policy, citing “law enforcement sensitivity.”

For President Trump, however, whose political priority is to restrict even legal immigration to the United States, the Remain in Mexico policy has been his single most successful effort: One asylum seeker subjected to the policy is known to have won the ability to stay in the U.S.

Oswaldo said his family fled their hometown outside Guatemala’s capital in February after his older sons refused to join MS-13 and gang members threatened to kill them. While in Mexico, he said police beat and robbed them, and local gangs tried to kidnap his 7-year-old daughter. They rode freight trains to the U.S. border, Oswaldo running for the trains with the baby on his chest in a bright pink carrier.

The family claimed asylum in April with U.S. authorities in Calexico, a small agricultural city in southeastern California across from Mexicali. Officials sent them back to Mexico, telling them to report to the border again a month later and 120 miles west, in Tijuana. There, they’d be brought across the border for a court hearing in San Diego, then sent back to Tijuana. Officials separated the case of Oswaldo’s eldest son, 21, from the rest of the family’s case.

“Life was already so difficult,” Oswaldo said. When U.S. officials returned them to Mexico, he said, “it was hard to take.”

After unveiling the policy in December, Homeland Security officials did not push the first asylum seekers back to Mexico until Jan. 28, launching the program in San Ysidro, south of San Diego. By the end of March, they’d expanded the policy east to El Paso.

In May, a federal appeals court ruled that the policy could continue until hearings on its legality in October. With the court’s blessing, the administration expanded the policy to the rest of the U.S.-Mexico border, and to any Spanish speaker, not just Central Americans. In less than three months, the number of removals quadrupled.

In July, U.S. officials began returning asylum seekers from the rest of Texas to Nuevo Laredo and then Matamoros, in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas.

The State Department gives Tamaulipas a level 4 “do not travel” warning — the same as Syria.

At least 141 migrants under the Remain in Mexico program have become victims of violence in that country, according to Human Rights First, a nonpartisan advocacy group. The nonprofit submitted a public complaint about the policy on Monday to the Homeland Security inspector general’s office and its Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties.

During a media briefing in August, Mark Morgan, the acting head of Customs and Border Protection, told The Times, “I would never participate in something I thought was illegal.” He added that the judicial system would ultimately “determine the legality” of the policy.

He said he was unaware of any incidents in which an asylum seeker was harmed under Remain in Mexico, but he said the U.S. didn’t track what happened to migrants once they were returned to Mexico. “That’s up to Mexico,” he said.

Roberto Velasco, spokesman for Mexico’s foreign ministry, said the policy was a “unilateral action” and that the U.S. was “solely responsible” for ensuring due process for asylum seekers returned to Mexico.

While saying the policy is for the immigrants’ own protection, Morgan said it was also intended to deter asylum seekers. He claimed, as the president often does, that many asylum applicants had fraudulent cases. “If you come here with a kid, it’s not going to be an automatic passport to the United States,” Morgan said. “I’m hoping that that message will get back.”

When Oswaldo and his family returned to Mexicali in May after their first hearing in San Diego, they had lost their place in a nearby shelter. They’re now on their fourth hearing.

Unable to obtain work permits promised by the Mexican government, and potentially years away from a final decision on his family’s asylum claim in the U.S., Oswaldo gestured with the candy box, saying it was all the family had.

“This is it.”

* * * * *

Daniela Diaz, a 19-year-old from El Salvador, emerged from a small tent wearing a pink jacket lined with fake fur.

Crowded into a Tijuana shelter, the tent had been the teenager’s home for five months as she waited on her asylum claim in the United States — except for the month she’d spent in U.S. detention.

Since fleeing San Salvador, El Salvador’s capital, late last year, Diaz has been repeatedly tripped up by the Trump administration’s chaotic rollout of Remain in Mexico.

In November, the Trump administration was engaged in intense negotiations with Mexico to get them to agree to take asylum seekers headed for the U.S. During that time, administration officials drafted a pilot program in California called Remain in Mexico. In e-mail exchanges, the officials struck key protections for asylum seekers. But when plans were leaked, the policy was put on hold.

In late January, officials pushed back the first asylum seekers from San Ysidro, but it was short-lived — in April, a federal judge in San Francisco temporarily blocked Remain in Mexico.

Then, just a few weeks later, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals allowed the Trump administration to resume the policy.

But two of the three judges raised concerns about its legality. One judge said the government’s legal argument to send migrants to Mexico was an “impossible” reading of the law.

“The government is wrong,” the judge wrote. “Not just arguably wrong, but clearly and flagrantly wrong.”

As for Diaz, she fled El Salvador last year after a Barrio 18 gang member threatened to kill her when she refused to become his girlfriend. A local police officer said he’d protect her but began to harass her instead, she said.

“He said, ‘I can rape you, I can do whatever I want to you, and make it look like the gangs did this, not me,’ ” she recounted the police officer saying.

She crossed alone from Guatemala into southern Mexico in November. In January, she arrived in Tijuana to join thousands of people waiting at the San Ysidro port of entry to register asylum claims.

In March, Diaz’s number finally came up. U.S. officials brought her into the San Ysidro entry, took her fingerprints, asked her a few questions and then sent her to the “icebox,” migrants’ term for U.S. immigration detention, she said. But shortly after, CBP officials took her to the gate leading back to Tijuana and gave her a notice to come back the next month for a court hearing.

“I can’t go back there, my life is at risk,” she recounted telling them.

She said they told her: “That’s not my problem anymore.”

On April 8, Diaz was taken from San Ysidro to San Diego for her first hearing — the same day a federal judge blocked the policy.

After several more weeks in detention, officers returned her to Tijuana, with another court date a month away.

Diaz told the judge in May that she wanted to represent herself, but he ignored her decision. She’d already called every lawyer on the list provided by the court. None answered. She’s still waiting in Tijuana.

Now, U.S. officials are returning asylum seekers at a rate of nearly 3,300 a week.

* * * * *

Judge Lee O’Connor’s raised voice ricocheted through his near-empty courtroom in San Diego.

“If I were to issue an in absentia order, where would it even be served?” O’Connor asked the administration lawyer.

“Your honor, on the address the court has.”

“The ‘general delivery,’ Baja California, Mexico?”

“Yes, your honor.”

“How is that an address?”

“Those are the addresses I was given,” the government lawyer responded. “I don’t know where they came from.”

Lawyers, advocates, U.S. asylum officers and judges see more than just bureaucratic dysfunction and sloppy policymaking — Trump officials, they say, intended to make it nearly impossible to win asylum in the United States under Remain in Mexico.

In the 9th Circuit ruling in May, one judge said Homeland Security’s procedures for implementing the policy were “so ill-suited to achieving that stated goal as to render them arbitrary and capricious.”

Earlier this summer in San Diego, on a day when roughly 100 Remain in Mexico cases had been heard, nearly all the judges had gone and security had left the courthouse — except for Judge O’Connor.

He was running hours late because he had tried to carefully explain to each applicant the new policy that was forcing them to stay in Mexico throughout an already complex U.S. immigration process.

Remain in Mexico has added to a backlog of more than 975,000 pending immigration cases. In July, one out of every four new cases were assigned to the Remain in Mexico program.

Sitting behind piles of paper, O’Connor weighed the government’s request to issue removal orders for a handful of asylum seekers who hadn’t shown up for their hearings that day. If O’Connor ruled in the administration’s favor, the decision could bar each applicant from the United States for at least a decade, if not permanently.

He launched into the administration lawyer, rattling off a list of legal violations.

The government had given no proof that a notice to appear in court was properly served to the asylum seekers. The government hadn’t submitted certified Spanish translations of case documents, which O’Connor noticed had glaring translation errors. And the address the government provided for dozens of asylum seekers whose cases he’d seen was “domicilio conocido” — loosely translated, “general delivery.”

“It seems like an awfully big coincidence that for 70 different people, they give the same address,” O’Connor told the government lawyer. CBP officers were putting “virtually no effort” into obtaining the legally required information, the judge added. “It gives me severe pause how this program is being implemented.”

Earlier that day, in a courtroom down the hall, Judge Christine Bither had heard her first cases from the program.

One couple had traveled from Mexicali to Tijuana and then across the border for their hearing in San Diego. But the government hadn’t filed their notice to appear with the court, meaning the immigration judge couldn’t see them that day, and they’d have to return to Mexico.

An administration lawyer handed papers to one family from Guatemala who spoke K’iche’. The lawyer told Bither, “Your honor, I am going to serve them with instructions in Spanish language and in English on how to present themselves.”

The judge retorted: “Neither of which language they speak.”

The majority of asylum seekers returned to Mexico under the policy are originally from Central America, so a sizable number speak only indigenous languages. But Homeland Security officials routinely don’t provide translation or use phone interpreters in removal proceedings, according to internal communications obtained by the nonprofit American Oversight and shared with The Times.

The Times reviewed a number of asylum seekers’ paperwork on which CBP officers had put incomplete addresses or provided no translation. And the free phone number the government provided for applicants to call for updates on their cases was an 800 number, which can only be used from within the United States.

“There’s some things that we’re still working through,” said Sidney Aki, a CBP official in charge of the San Ysidro port. He conceded that officers had made mistakes implementing the policy, saying they were in uncharted territory.

As of the end of July, only 2,599 Remain in Mexico cases had been decided, with another 23,402 cases pending in immigration courts across the country — nearly double the number from one month earlier, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University. At that point, not one person had won asylum.

A little more than 1% of the asylum seekers had managed to find legal representation from Mexico.

O’Connor ordered that the government’s removal proceedings against the absent asylum seekers be terminated. He’s not the only one; overall, in roughly 60% of the decisions reached so far under Remain in Mexico, immigration judges have closed the government’s case against the asylum seekers, according to the TRAC data.

“If the government intends to carry out the program,” O’Connor ruled, “it must ensure due process is strictly complied with and statutory requirements are strictly adhered to. That has not been shown in any of these cases.”

* * * * *

Nora Muñoz Vega watched her son kick a soccer ball at Buen Pastor shelter in Juarez. As 9-year-old Josue David played, his 29-year-old mother weighed a difficult decision: Keep waiting in Juarez on their asylum case or take a bus, sponsored by the Mexican government, back to Honduras.

Asylum seekers stuck in Juarez under Remain in Mexico have hearings scheduled into 2020. But unable to find work in Mexico without a permit, and too scared to venture out, Muñoz Vega said the few weeks until her second hearing seemed like an eternity.

In its May ruling allowing Remain in Mexico to resume, the 9th Circuit relied in part on assurances from the U.S. that Mexico was providing for the asylum seekers. Yet none of the migrants to whom The Times spoke had been able to obtain a work permit: All were staying in shelters run by churches or non-governmental organizations, or hotels when shelters filled up.

Through “voluntary return,” the Mexican government, along with the United Nations, is facilitating the Trump administration’s effort to get asylum seekers to give up on their cases. More than 2,000 Central Americans have taken free rides back to their home countries under the U.N. program, which is funded by the U.S. government.

“We are similarly concerned with the implications,” the U.N. migration agency wrote on Aug. 13 to a group of NGOs concerned about its role in Remain in Mexico, according to a letter obtained by The Times. The agency said it was taking steps to ensure the returns were in fact voluntary.

Although it’s unclear exactly how many asylum seekers under Remain in Mexico have gone home, a number appear to be growing tired of waiting and are crossing the border illegally.

On the viaduct between Juarez and El Paso, Border Patrol Agent Mario Escalante watched from the U.S. side as Mexican National Guard units patrolled on theirs.

Escalante was born in El Paso but said he practically grew up in Juarez, with family on both sides of the bridge for generations. Grisly murders had become commonplace in Juarez, he added. “It’s the culture; you get used to it.”

But asked whether Juarez was safe for the asylum seekers U.S. officials had sent there, Escalante brushed off the question.

When his radio crackled, he sped toward a popular crossing just beyond the international bridge. A group of Central American women and children cowered in the shade.

“It’s difficult to watch,” Escalante said. “The need’s gotta be pretty great.”

One woman with her son raised her head. It was Muñoz Vega, the Honduran mother.

* * * * *

Across the country, a number of federal asylum officers have quit, and a handful are refusing to implement Remain in Mexico, half a dozen asylum officers and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services personnel told The Times.

They say the Trump administration is forcing them to violate the law in implementing the policy, end-running standards set by Congress and intentionally putting vulnerable asylum seekers in harm’s way. Most requested anonymity due to fears of retaliation.

In June, the union representing federal asylum officers in the Washington, D.C., area filed a brief in support of the lawsuit against Remain in Mexico.

“Every day, it gets a little bit worse,” said one asylum officer in California who refused to screen migrants under the policy.

Generally, before Remain in Mexico, asylum seekers at the border would receive a “credible fear” interview. The asylum officers, many of whom are attorneys, screen for fear of persecution in the asylum seeker’s home country based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion or being part of a particular social group. Congress set “credible fear” as an intentionally low bar to help ensure the U.S. did not violate the law by returning people to harm.

But according to administration guidelines under Remain in Mexico, only asylum seekers who proactively express a fear of returning to Mexico — not their home countries — are referred by CBP officials to asylum officers, and for an entirely new interview process. That process screens them for likelihood of persecution in Mexico.

In these interviews, asylum officers also have to use a much higher legal standard. Essentially, instead of proving a 10% likelihood of persecution in their home country, asylum seekers have to prove a 51% likelihood of persecution in Mexico. That standard is generally reserved for a full hearing before an immigration judge.

In reality, the standard being used under Remain in Mexico is nearly impossible, another asylum officer said. “No one can pass.”

And even when officers decide that the asylum seekers meet the higher standard and would be in grave danger in Mexico, Homeland Security officials are overruling them and returning them anyway, according to the six USCIS personnel.

According to interviews with asylum seekers and officers, as well as USCIS statistics shared with The Times, many asylum seekers under Remain in Mexico are being removed without any interview at all.

Against its own guidelines, those sources say, Homeland Security officials also are returning children, people with disabilities and other medical conditions, and pregnant women. Lawmakers have demanded an inspector general investigation of the alleged violations.

The second asylum officer said she recently sounded the alarm after seeing a spate of women in late stages of pregnancy being turned back to Mexico. She was told that CBP does not consider a late-stage pregnancy to be a serious medical condition.

“They don’t want them to drop any babies on U.S. soil,” the asylum officer said.

A third asylum officer said they’re required to conduct the more complex Remain in Mexico interviews — sometimes lasting more than five hours — with children too young to speak.

Four officers described cases of asylum seekers who said they had been kidnapped in Mexico, then beaten and raped. Once their families sent money, the kidnappers released them. But when the victims fled for the border, the asylum officers had to turn them back. Kidnappers are now waiting outside ports of entry for the U.S. returns, officers said.

“In 99% of the interviews, they said they faced harm in Mexico, and we sent them back,” the third asylum officer said.

One asylum officer said she routinely woke up in a sweat from nightmares.

“How long can I do this and live with myself?” she said. “I think about these people all the time … the ones that I sent back. I hope they’re alive.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.